1.3 What Makes a Theory?

Criminology is an inherently interdisciplinary field, meaning that criminologists base their understanding of the causes of crime on existing theories in psychology, sociology, economics, politics, and biology. They then create new theories to paint an even clearer picture. In this section, we will discuss what it takes to create a theory and what that process looks like.

The Open Education Sociology Dictionary defines theory as a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns. In other words, a theory helps people make sense of what they are seeing. In criminology, that means explaining what is happening in terms of crime and criminal behavior. Theories help us classify, organize, explain, predict, and understand some phenomena. For example, one theory may try to explain the increase in crime in Portland during the pandemic by focusing on why a bunch of kids who are home from school for a long time, who live in the same neighborhood, and who all have tough home lives may come together and act out in violent ways. Later, this book discusses specific theories that attempt to explain such a situation. However, for now, let’s start with the basics.

You might be wondering where theories originate or how people come up with them in the first place. We start with a question. Why is what we are witnessing happening? Why is gun violence increasing? How can we explain this phenomenon? To respond to our chosen question, we create an educated guess, called a hypothesis, based on what we have seen. A hypothesis is a reasonable possible explanation of why we think a phenomenon is occurring. It is not random. It must fit with what we are seeing, and it must be simple enough that we can test it to see if we are onto something. A hypothesis is the beginning of a theory.

Based on the definition of a theory, it may seem like just about anyone can come up with a possible explanation for what is happening and claim it is a legitimate theory. While it is true that anyone can come up with an idea to explain some phenomenon, legitimate theories involve scientific and systematic study. You can think of your uncle’s idea on why people commit sexual assault as a “lower case t” theory, while feminist criminologists’ descriptions and unpacking of gender roles based on decades of research is an “upper case T” theory. In other words, a good theory involves more than just personal speculation.

Criteria for Criminological Theories

Ronald Akers and Christine Sellers (2012) established a set of criteria to guide criminologists in evaluating theories. They said a “good” criminological theory must meet these six criteria:

- logical consistency

- scope

- parsimony

- testability

- empirical validity

- usefulness

Logical consistency is the most basic element of any theory. It requires that the theory makes sense. Is it reasonable? Does it make sense from beginning to end? That would make it both logical and consistent.

Scope refers to what is covered or addressed by the theory. Does it apply across gender identities? How about different types of crimes? Are both adults and juveniles covered? The wider the scope, the more the theory explains. The more a theory can explain (while still meeting the other five criteria), the better it is.

Parsimony refers to keeping a theory clear, concise, and simple. A theory with parsimony does not try to explain too much. Parsimony may seem strange coming after scope, since they appear to have opposing definitions, but they are not actually contradictions. We do want that big scope, but only if it is simple and makes sense. When done correctly, scope and parsimony are complementary.

Although we cannot examine our theories through a microscope, they must still be testable. When a researcher tests a theory, they are basically trying to prove it wrong or falsify it. That is not a bad thing. Every theory must be open to possible falsification because the more it is tested, the stronger it becomes. If someone falsifies a theory, they also find what makes it more accurate, and that discovery updates the knowledge base upon which the theory is built. Once that is done, it is tested again. And again. And again.

After many tests through a variety of approaches to research, the theory ends up stronger than ever and is supported by evidence from each test or study. This evidence gives the theory empirical validity, which means we can see it in research (empirical), and we are seeing what the theory claims we will see (validity). In other words, we see evidence in research that confirms the claims of the theory.

Finally, usefulness refers to what we do with what we know. The theory should be applicable to real life. Since our entire goal is to learn more about the why of crime, a useful criminological theory will tell us what to do in real life to interrupt the criminal patterns it addresses.

Operational Definitions

How do we test something abstract that cannot be observed in a microscope? We have to make it less abstract. We use operational definitions, to specifically describe a concept so we know exactly what we are looking at and what we are looking for. This allows us to measure and test the concept we are describing.

Let’s say a theory claims that grand romantic gestures cause people to fall in love. First, we need to know exactly what is meant by a grand romantic gesture. We also need to determine how to know if someone has actually fallen in love. In a study to test this theory, we might define grand romantic gesture as the act of inviting someone on a date by using a flash mob or trailing a banner behind an airplane (figure 1.3). By narrowing down grand romantic gestures to just these two specific actions, the research can be targeted. There is no confusion about what is being used to cause something else to happen.

The next challenge in this example is figuring out how to measure whether the person on the receiving end of the grand romantic gesture has fallen in love. That is more than we can get into in this chapter—we all know love is more complicated than what can be cleared up in one book. How might you operationally define love?

For a more topical example, what if we have a theory that says someone who commits crime has a low level of self-control? How can we test that theory? First, we have to operationally define the two concepts named in this theory: committing crime and a low level of self-control. What crimes are we talking about? Murder? Assault? Burglary? Vandalism? That’s quite a range of actions that we need to define. Also, if there is a low level of self-control, then that means there are other levels, too, such as high or medium levels of self-control. How do we define those levels, and how do we know someone’s level? How can that be tested and identified? What is our operational definition of self-control, and how is it measured and divided into different levels?

There are entire classes and textbooks dedicated to this issue alone and how to do this type of research responsibly and scientifically. For now, let’s just talk about it broadly.

Variables and Spuriousness

The two concepts of crime and self-control from the previous example are variables in this type of research. These variables—concepts, factors, or elements in the study—can be tested to see what sort of influence one has on the other. For example, we could test someone’s self-control by exposing them to a temptation (like a sweet treat), telling them they are not allowed to have it, leaving the room so they are alone with the temptation, and then seeing if they go for it anyway. The Marshmallow Test is a famous—and fun to watch—example of testing self-control among children. You have the option to watch the 5-minute video in Figure 1.4 while considering these questions: How do they operationalize “self-control” in this study? What might be causing spuriousness in this study?

Going back to our experiment, we could measure criminal behavior by looking at an individual’s criminal record. Will the same people who jump at the presented temptation also have criminal records? Does that show us that someone who commits crime has a low level of self-control? Could we then say these two variables appear to be correlated (related)? Others would then come along and test our two variables in different ways to see if the results are the same. Every time this happens, we learn even more about the relationship between crime and low levels of self-control, and we learn more about the proposed theory.

One snag in our experiment could be other variables coming into play that we missed or ignored. Is a person giving into the temptation because they have low self-control, or is there another factor making them cave? Also, what if the temptation we chose is not actually tempting to every participant in our study in the same way? What if someone is really hungry or has been dieting and maybe craving a donut? What if some participants don’t really like donuts or just ate a big lunch? In other words, something else could be causing the outcome we see. Spuriousness occurs when two things appear to be meaningfully correlated but are not due to the influence of another variable.

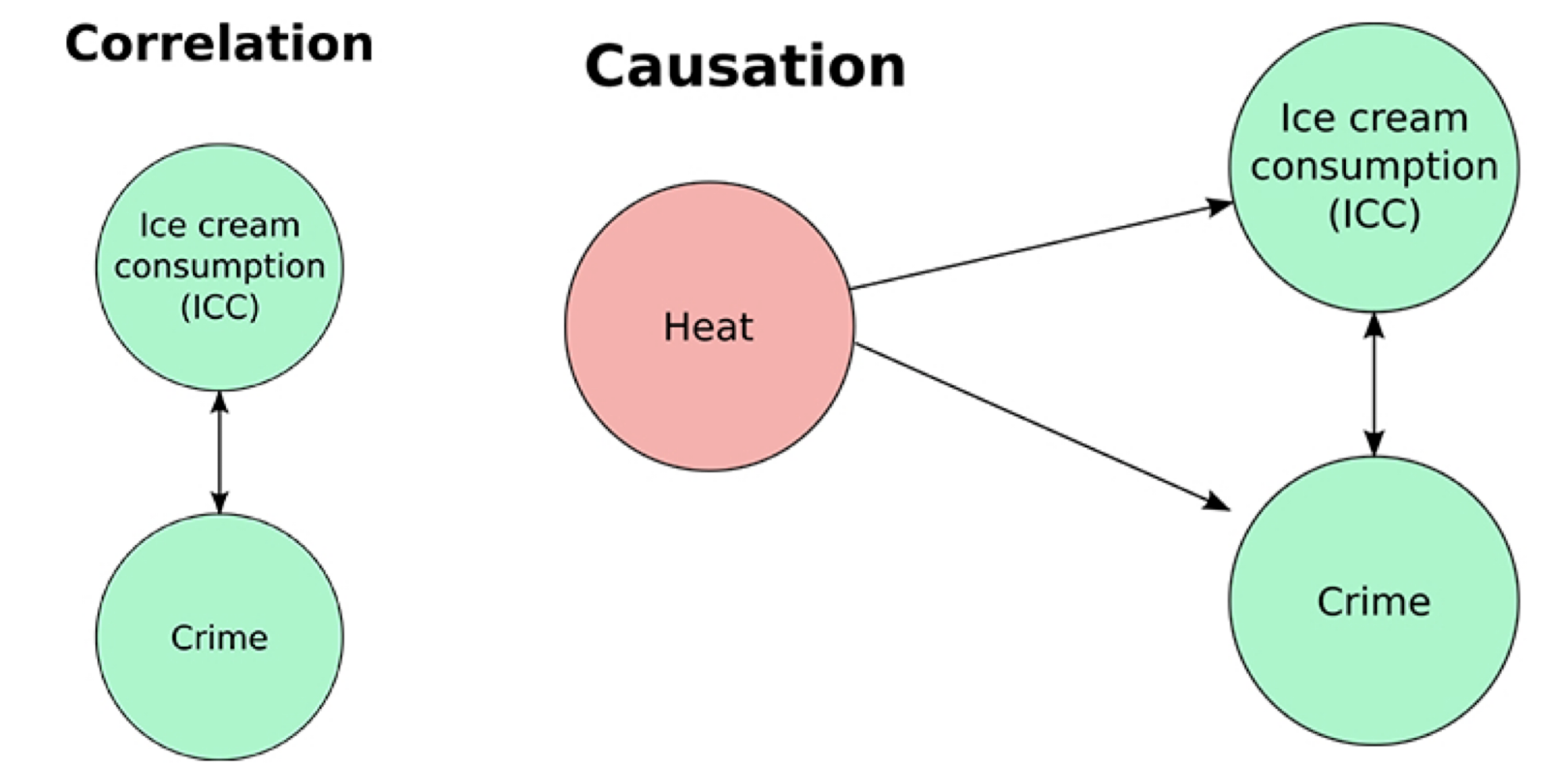

For example, research shows that ice cream sales and murder rates are positively correlated (Cohen, 1941; U.S. Department of Justice, 1969; Peters, 2013). This means that when ice cream sales go up, murder rates also go up, and vice versa. At first glance, someone may claim that ice cream is causing people to commit murder or that committing murder makes people hungry for ice cream. What do you think might be a better explanation? Can you think of a third variable that might cause ice cream sales and murder rates to both increase?

Consider the weather and what happens during summertime in Oregon. Thankful for the sunshine after months of rain, a lot more people spend time outside. Also, many homes in Oregon do not have air conditioning, so people may be more comfortable outdoors during heatwaves. A popular activity during hot periods is to eat ice cream. It is cold, refreshing, and delicious—thus, we see an increase in ice cream sales.

In some areas, more people being outside can lead to more conflict. For example, do you think gang-related murders are more likely to happen when it is cold and the group is hanging out inside someone’s garage, or when it is warm outside and the group is out and about, possibly encroaching on a nearby gang’s territory? When we consider how warm weather changes people’s behavior in this overly simplified example, it is possible to see that the weather itself can be a factor in both an increase in ice cream sales and an increase in murder rates and that ice cream and murder are actually in no way related (figure 1.5). If you want to see more silly examples of spuriousness that demonstrate the difference between correlation and causation, you have the option to read more at Spurious Correlations [Website].

All the criteria discussed here are important for making a good theory, but there is one last thing to consider: What’s the point? A criminological theory needs a purpose. A good criminological theory will help guide policies and practices to prevent or reduce crime. For example, a theory that connects childhood trauma to an increased likelihood of delinquent behavior in adolescence tells those working with at-risk youth that they may be able to prevent some offenses by intervening to protect kids from trauma or to help them work through what they have experienced.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for What Makes a Theory?

Open Content, Original

“What Makes a Theory?” by Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Jessica René Peterson.

“What Makes a Theory? Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Theory” definition from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary by Kenton Bell is licensed under CC BY SA 4.0.

Figure 1.3. “Flash Mob” by DMatUFWiki is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 1.5. “Ice cream and crime-causation” and “Ice cream and crime correlation” by Wykis are in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 1.4. “The Marshmallow Experiment – Instant Gratification” by FloodSanDiego is shared under the Standard YouTube License.