5.2 The Social Structure

Auguste Comte, a French engineer turned philosopher, is often credited for coining the term sociology and founding the positivist movement. Rather than studying individuals and individual influences on behavior, Comte and other early sociologists were interested in a broader understanding of our society and culture. They wanted to study the ways that societies formed and functioned, how social structures influenced behavior (especially at a group level), and how cultures came to attribute meaning to behavior. Deviance and crime—remember the difference from Chapter 1?—are significant parts of these topics, so this is where sociology meets criminology. Many criminological theories are rooted in sociological thinking, and many also incorporate elements from the other approaches we have already discussed in this book.

First, what does social structure actually mean? In sociology, social structure refers to the framework and relationship between institutions, groups, and norms in a society. This includes social class, politics, economy, religion, behaviors, values, and more. So essentially, social structure is all the things that make up a society. It is a key concept in the field of sociology. See the following Learn More section for a current example of social structural concerns. Social structural theories of crime emphasize differences between groups in society, such as class, education, gender, race, or ethnicity. Distinctions between groups can be created by both formal (e.g., laws) and informal means (e.g., peer interactions).

We must again consider the social position of these theorists as they examine social structures. Early sociology, like criminology, prioritized the work of white men almost exclusively. This means that the lens through which societies and cultures were initially assessed typically came from a privileged position at best. Social norms and expectations such as traditional gender roles were embedded in many early attempts at explaining society and culture. We know that social norms change as societies change and progress, so definitions of deviance have certainly changed since many of these theories were introduced. We need to always consider what people are deviating from and according to whom. This is not to say these theories are wholly wrong or without value. Rather, it is a reminder to keep the theorists’ personal perspectives or biases (and your own) in mind.

Learn More: Attacking the Capital

On January 6, 2021, the world watched as American citizens stormed the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. (figure 5.2). Tensions had been high for months. The country was still in the grips of COVID-19 and had just experienced a summer filled with protests against police brutality of the Black community. Following the nationwide presidential election in November of 2020, Trump supporters began talking about a coup.

On January 6th, a joint session of Congress was in the Capitol formalizing the election of Joe Biden by officially counting and recording the electoral college votes from each state. This is a process that is led by the vice president and has occurred in every presidential election in U.S. history. Interestingly, when Donald Trump was elected president, Joe Biden was serving as vice president and led the same ritual to formalize that election. In 2021, the vice president was Mike Pence, and he refused to participate in Trump’s claims that the election had been stolen and Biden’s victory should be rejected.

While Congress was conducting its responsibility in the Capitol, Donald Trump spoke at a rally from which thousands marched down the street to the Capitol building. At least 2,000 of these individuals breached the security measures and entered the building. Many participated in vandalizing and looting in the Senate chamber and several offices, assaulting Capitol police officers and reporters, and searching for members of Congress while making threats of harm (including the murder of Vice President Mike Pence).

During this insurrection, five people were killed and 138 police officers were injured. Later, four more officers who survived that day died by suicide. In the time since, over 1,000 of the participants have been charged with federal crimes for the attack. As of July 2023, 629 of those had pleaded guilty and 127 had been found guilty at trial. Many of those convicted for their actions on January 6th were charged with sedition, a slightly lower charge than treason.

In this chapter, we look at theories about how society affects or even causes crime. There was a lot of upheaval in the country and society around the time of this particular event. We are going to talk about how different sociologists have attempted to explain criminal behavior and its link to social structures.

Durkheim and Anomie

Émile Durkheim was a French sociologist in the 1890s who viewed economic or social inequality and crime as natural and inevitable in society (figure 5.3). In fact, he thought that crime was not only normal, but necessary because it provided essential functions, such as defining a society’s moral boundaries and creating bonds among members through shared ideas of right and wrong. In other words, criminals are created by and symbolic for society.

In his book Division of Labour in Society, Durkheim (1997) explained societal development as moving from societies that were mechanical to societies that were organic. He described mechanical societies as primitive and agrarian, with all members performing the same basic functions based on gender roles. The constant, routine interaction between members of a small and tight-knit community led to strong uniformity in values, or a collective conscience. However, as a society like this develops, industrializes, and grows, it cannot function the same way. Labor has to be distributed and specialized. For example, most of us probably buy most of our groceries from a store and work a variety of non-farming jobs to afford them. In other words, we no longer perform the same duties as some of us are farmers, hair stylists, or bank tellers. When societal growth happens, people have to rely on other groups of people. This is when a society transforms into an organic society.

As a society grows and collective conscience fades, laws have to regulate interactions between people and help maintain some form of solidarity. On a smaller but relatable scale, think about the difference between working on a group project with two classmates versus eight classmates; you probably need more ground rules as the number of people increases. Durkheim saw the instability that could occur during the transition between society types as a state of normlessness, or anomie. Because this period lacks rules for behavior, Durkheim saw this as a prime time for social problems, such as crime, to thrive.

Durkheim’s sociology is much broader than the study of crime, but his work set the foundation for the future of criminological theory (Boyd, 2015). In Durkeim’s book Suicide (2002), he used statistics to demonstrate that suicide rates differed across social groups and that this pattern was relatively stable over time. Suicide rates were higher among industrial and commercial professions than agricultural ones, higher among urban city dwellers than people who lived in small towns, and higher among divorcees than married people. He believed that the differences in suicide rates among groups could be linked to anomic social conditions.

Strain Theories

One of the main theorists who was influenced by Durkheim’s work was Robert K. Merton. Merton (1938) took the concept of anomie and applied it specifically to American society. He thought many human appetites originated in the culture of American society rather than naturally. It is helpful to consider what was happening in the country at the time Merton was doing his work. The country had recently experienced the Great Depression (1929–1939) followed by World War II (1939–1945). After these two global catastrophes, the United States was financially better off than anywhere else as it was the global leader in the worldwide economy. During this time, soldiers returned home from war to free higher education (through the G.I. Bill) and a new residential construction boom that made for affordable and easily accessible housing. They also participated fully in the baby boom, which further boosted the economy.

All of this contributed to the rise of the “American Dream,” which many imagined as a blissful, white, nuclear family (mom, dad, and two kids) that owns a house with two cars in the driveway, a picket fence, and a dog (probably a golden retriever). However, no matter how you conceptualize the American Dream, most people would define it as achieving economic success in some form. The culturally approved method of obtaining the American Dream is through hard work, innovation, and education, especially a college degree. Merton recognized that this fantasy life is not available to everyone because the structure of American society is restrictive, and some people or groups are not given the same opportunities to achieve this cultural goal. When there is a disjunction between the goals of a society and the appropriate means to achieve those goals, anomie may result (figure 5.4).

When someone does not achieve a desired societal goal, they may feel strain or pressure. Merton claimed that everyone in American society was socialized to desire the same goals, regardless of their background. Consequently, those in lower socioeconomic classes are the most likely to experience obstacles to success and the resulting strain. This is the basis of Merton’s strain theory. Adolphe Quetelet, the theorist discussed in Chapter 3 who studied crime rate trends in France, would call this relative deprivation, which is inequality and gaps between wealth and poverty in a single place. Quetelet thought that this condition created opportunities for crime.

Let’s stop and really think about this idea. Imagine a kid living in a high-income household. That child is likely to live in a nicer neighborhood with good recreational and health-related resources. They may have access to private schools, tutors, and extracurricular activities that result in a better education and higher chances of getting into college. Rather than taking a low-paying after-school job to help pay the bills or cover some of their own expenses, a kid from a higher-income family may be able to volunteer their time or work in unpaid positions, which could give them access to career networks. From the very beginning, a higher socioeconomic status and social class provides individuals with opportunities that help them get closer to reaching our institutionalized goals. Those in lower socioeconomic classes do not have those same opportunities. And this is before even considering how racism, sexism, and other prejudices affect childhood and available opportunities.

For a very real and current example of relative deprivation, think about the giant gap that exists between the “haves” and “have-nots.” There is a growing divide between even the “have somes” (the middle class) and the rich. According to the Federal Reserve, the richest 1% of Americans hold 31.3% of the wealth in the entire United States. For comparison, the poorest 50% of Americans hold less than 2.4% (Federal Reserve, 2023).

Merton’s Adaptations

Now, let’s get back to Merton’s theory and why goals, means, blocked opportunities, and relative deprivation matter for crime. Merton identified five different ways that people adapt to the goals of a society and the means to achieve those goals (figure 5.5). They include conformity, ritualism, innovation, retreatism, and rebellion.

| Adaption to Structural Strain | Want the American Dream? (Goals) | Follow conventional societal rules? (Means) |

|---|---|---|

| Conformity | Yes | Yes |

| Ritualism | No | Yes |

| Innovation | Yes | No |

| Retreatism | No | No |

| Rebellion | Reject culture and strive for change—may use legitimate or illegitimate means to do so | |

According to Merton, conformists are the people who embrace both a society’s conventional goals and the means of achieving them. In other words, conformists desire all the things that come with the American Dream and they take the “ideal” route to get there, such as by going to college and getting a well-paying respectable job. Merton believed that this was the most common adaptation when anomie is absent in a society. However, there are other ways that people may adapt, especially if they do not have the same ability to achieve the goals through the accepted means.

Ritualists are not really concerned with becoming wealthy or meeting other major societal goals. However, they are still content with or enjoy the traditional practices in society. An example of ritualists might be people who run a “mom and pop” local business. Perhaps ritualists feel safe following societal expectations even if they do not aim to, or simply are unable to, attain the ultimate goals.

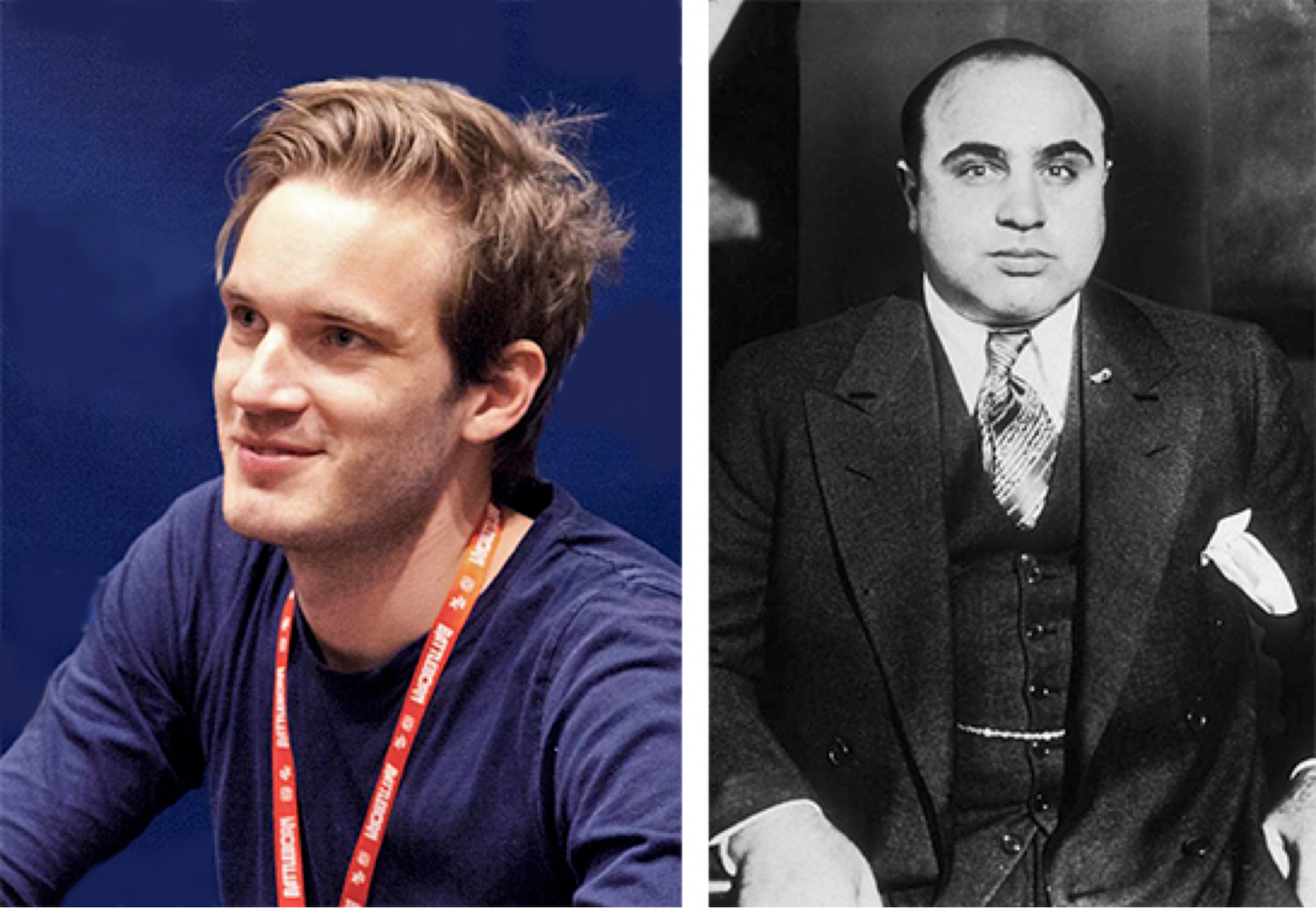

Innovators are people who very much want to reach conventional goals but reject or are incapable of reaching them through socially accepted means. Think of someone like Mark Zuckerberg or famous YouTuber PewDiePie; neither of these individuals followed the traditional means of achieving wealth, but they certainly attained the institutional goals (figure 5.6). Although these examples included legal routes, innovation is the adaptation that is most closely linked with crime. If you aren’t one of those types who make it big by following conventional means, what other routes might you take? For many, the answer might be selling drugs, stealing, or defrauding people out of their money. The popular show Breaking Bad is a great example of innovation as an adaptation to blocked opportunities.

There is one thing that separates retreatists from rebels. Neither are after the conventional goals or means of society, but rebels substitute alternative goals and means. For example, these may be radicals and revolutionaries who call for alternative lifestyles and a new social order. After George Floyd was murdered in 2020, a group protesting police brutality established the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ), later known as the Capitol Hill Organized Protests (CHOP) in a Seattle neighborhood (Holden, 2023). The people engaged in this demonstration illustrate Merton’s rebellion adaptation. In contrast, retreatists are “in the society but not of it” (Merton, 1938, p. 677). In other words, retreatists withdraw from society and may be voluntarily or involuntarily unhoused, survivalists, people in addiction, or people with severe mental illness. A stereotypical “pothead” who drops out of high school is a classic example.

Let’s put all of these concepts together. Merton saw U.S. society as having agreed-upon conventional goals and means to achieve them that most people embrace. However, in an unequal and inequitable society, not everyone can access either the means or goals, and this causes (structural) strain. While crime can occur among more than one adaptation to such circumstances, Merton saw innovators as the most crime-prone because they still want to achieve institutional goals but their access is blocked. These are the components and concepts that constitute strain theory. Figure 5.7 illustrates how the way someone adapts may lead to criminal behavior.

Activity: Kai and Adaptations to Strain

In 2013, Caleb Lawrence McGillvary, who is known better simply as “Kai,” became an internet sensation when his interview with a reporter went viral (figure 5.8). In it, Kai describes how he stopped a man, with whom he had been hitchhiking, from further injuring a person after hitting them with his car. In 2023, Netflix released a documentary about Kai titled The Hatchet Wielding Hitchhiker that explored his life, crimes, and fame.

Discussion Questions

- Do you think Kai has conventional goals according to Merton’s strain theory?

- Do you think Kai is following conventional means according to Merton’s strain theory?

- Which of Merton’s adaptations do you think Kai best fits? Explain.

- What societal factors do you think contribute to Kai’s behavior? Explain.

Agnew’s General Strain Theory

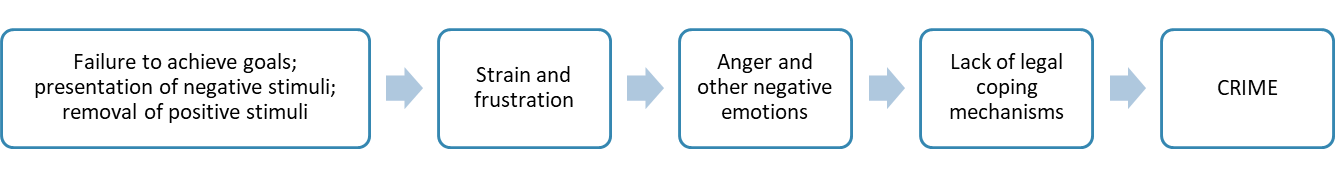

Taking Merton’s ideas about structural strain resulting from imbalances in society, Robert Agnew (1992) applied the concept of strain to people of all social classes and economic positions to explain crime. He identified strains that occur at the individual level rather than focusing on the broader, structural level of society as Merton did. Such sources of strain include:

- failure to achieve positively valued goals

- removal of positively valued stimuli

- presentation of noxious (negative) stimuli

The first type of strain is quite similar to what Merton described: the inability to achieve a goal that you desire, such as wealth, due to blocked opportunities. The other two types of strain that Agnew identified sound complicated but are quite simple. The removal of positively valued stimuli means losing something you like. This could include getting laid off from your dream job, losing a loved one or pet, moving to a new city away from your friends, or even experiencing your parents’ divorce. Presentation of noxious stimuli refers to something unwanted entering your life. Examples of this might include experiencing abuse or discrimination from a loved one or acquaintance, developing health problems, or getting a new boss who is a major jerk. Agnew believed situations like these could cause strain on a person, even if they were anticipated or vicariously experienced by imagining the feelings of someone who was directly impacted.

Importantly, Agnew did not claim that these types of strain directly caused crime. Instead, they led to a negative affective state that could include anger, depression, disappointment, or fear. It is the negative affective state that leads to crime, especially among those who do not have support to help them cope, escape painful situations, or boost their self-confidence. See figure 5.9 for an illustration of Agnew’s general strain theory.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for the Social Structure

Open Content, Original

“The Social Structure” by Jessica René Peterson and Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Learn More: Attacking the Capital” by Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Activity: Kai and Adaptations to Strain” by Jessica René Peterson and Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.5. “Merton’s Adaptations to Strain” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.7. “Diagram of Merton’s Structural Strain Theory” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.9. “Diagram of Agnew’s General Strain Theory” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“The Social Structure Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Durkheim and Anomie” is adapted from “Crime and Social Norms” in Introduction to Criminology by Dr. Sean Ashley, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include substantially expanding and rewriting.

“Strain Theories” is adapted from “Strain Theories,” in Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Brian Fedorek, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include substantially expanding and rewriting.

Figure 5.2. “DC Capitol Storming IMG 7965” by TapTheForwardAssist is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.3. “Émile Durkheim” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 5.4. “people in street at nighttime” by Andreas M is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 5.6, left.”PewDiePie at PAX 2015 crop” is in the Public Domain, CC0 1.0.

Figure 5.6, right. “Al Capone-around 1935” is in the Public Domain, courtesy of the Federal Bureau of Investigations.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.8. “Kai, Hatchet Wielding Hitchhiker, Amazing Interview w/ Jessob Reisbeck” by Jessob Reisbeck is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.