6.4 Subcultural Theories of Crime

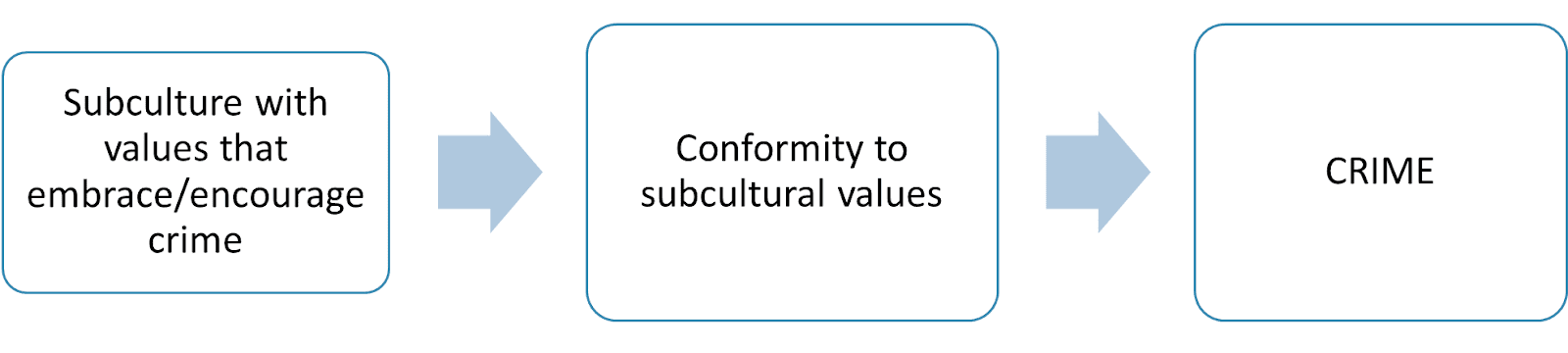

Culture consists of tangible things that you can touch as well as ideas, attitudes, and beliefs. The style of our buses in the United States compared to those in other countries becomes part of our culture, just as our norms about how close you should stand to other passengers on the bus are part of our culture (Conerly et al., 2024). Societies have a mainstream culture consisting of the conventional norms and status quo. Oftentimes, subcultures will also be present in a society. Subcultures are groups that share a specific identity that differs from the mainstream majority, even though they exist within the larger society (Conerly et al., 2024). Subcultural theories of crime view crime as a result of either conformity to a subculture or rebellion against the mainstream culture.

First, take a look at the context in which many of these theories developed. Following the housing boom and baby boom of the 1950s, the United States moved into an era of revolution in the 1960s and ’70s. Many social norms were challenged, ranging from rebellions against mainstream music and clothing to larger demands for change in civil rights for marginalized groups. Inequalities were brought out into the open and sociologists took notice.

Merton’s strain theory, as we discussed in Chapter 5, made a lot of sense to some criminologists in this setting, and they began to see how well it fit with certain groups or situations. Scholars within The Chicago School expanded the notions of strain and anomie, building upon Merton’s work, to explain how this might apply to everyday life for a broader population. Many subcultural theories combine elements of structural theories with components of learning and interactionist theories to explain how subcultures develop and may facilitate criminal offending. In this chapter, we will discuss theories on the subculture of violence, cultural deviance, and the code of the streets, as well as criminological explanations of gang formation, including status frustration theory and differential opportunity theory.

Deviating From the Dominant Culture

The dominant culture in a society is promoted as the only acceptable way to live, behave, and believe, whether or not smaller groups who are not represented in this dominant majority agree. The norms and values of the dominant culture are even considered “right” when they contradict what is actually preferred by smaller, less powerful groups. These other groups often develop their own subcultures, which may not align with the dominant culture and are considered deviant.

Among the sociologists in The Chicago School, the subcultures they witnessed in urban Chicago were the subject of much of their research. Most of the (especially early) theorists were part of the dominant culture in the United States. However, it is in this area that Black scholars were finally able to gain prominence by explaining what the experience is like from inside a subculture, rather than looking in from the outside as many white scholars did.

For decades, W.E.B. Du Bois, a Black sociologist working in the early 1900s, was excluded from discussions on criminological and sociological theories because of his race. Many of his assertions were later claimed by or credited to white scholars who made similar arguments. He also struggled to get published in academic journals and major periodicals because they did not accept work from Black scholars. His work did not become truly appreciated in the mainstream until nearly 100 years after it was presented. Du Bois studied crime in Black communities long before those in The Chicago School began their work. Du Bois is noted for his theories on racial injustice, the social construction of crime, and the criminalization of Blackness. He argued that Black communities experienced racist social and economic exclusion, creating an area where crime was one of the few options for survival.

Later, when Shaw and McKay published their social disorganization theory in the 1940s, they were given credit for discovering much of what Du Bois had already described. His work still gets conflated with theirs, despite the fact that Shaw and McKay looked at social control within neighborhoods, whereas Du Bois recognized the societal systems that caused the phenomena that led to social disorganization in the first place. He argued that resolving issues of racial exclusion, oppression, and economic injustice would drastically reduce criminal behavior. For some criminologists,these mechanisms of marginalization explain the development of subcultures that embrace or facilitate criminality.

The Subculture of Violence and Cultural Deviance Theory

Marvin Wolfgang and Franco Ferracuti (1967) developed the subculture of violence theory, which states that certain norms and values in working class communities can explain violent crime. According to these researchers, violence is an expected and normalized response to conflict in these communities. It is not viewed negatively, but rather as just the way things are done. For this reason, Wolfgang and Ferracuti claimed people in this subculture are always prepared for interactions to turn violent. There is no guilt associated with the violence, according to Wolfgang and Ferracuti, and it is typically encouraged and valued. However, reacting to situations with violence is a learned behavior, which means it can be unlearned.

Walter Miller also believed that the entire lower class in America had its own subculture, with values and norms that differed from those of mainstream America. Miller’s (1958) cultural deviance theory claims that lower-class parents socialize their children into six focal concerns that run counter to mainstream culture, including trouble, toughness, smartness, excitement, fate, and autonomy (figure 6.17). According to Miller, adhering to these values is simply an act of conformity to the subculture held by the lower class. However, such adherence leads to delinquency and crime.

| Focal Concern (Value) | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Trouble | The value of being able to get yourself out of your own personal problems; can actually elevate your social status within the subculture |

| Toughness | The value of strength and ability and willingness to fight, especially to uphold your social reputation |

| Smartness | The value of being able to outsmart or con others to achieve material gains (street smarts) |

| Excitement | The value of thrill-seeking, especially as a way to escape the mundane existence of being in the lower class |

| Fate | The belief in destiny and luck; can disregard accountability and responsibility for one’s actions especially as many in the lower class do not believe they will live long lives |

| Autonomy | The value of independence and not being controlled by anyone |

The Code of the Streets

“It’s easy to be judgmental about crime when you live in a world wealthy enough to be removed from it. But the hood taught me that everyone has different notions of right and wrong, different definitions of what constitutes crime, and what level of crime they’re willing to participate in.”

Trevor Noah, South African comedian, political commentator, and former host of The Daily Show

In 1999, Elijah Anderson, a Black sociologist, studied Black neighborhoods in Philadelphia building on the work of W. E. B. Du Bois. In his book, The Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City, he named and detailed aspects of street culture that he said stresses a hyperinflated notion of manhood centering on the idea of respect. According to Anderson, respect was defined as being treated right or being granted deserved deference.

In this street culture or code of the street, a man’s sense of worth is determined by the respect he can command in public. Anderson found that since these young Black men lived in a subculture that was violent due to lack of jobs and basic public services, stigma related to race, and hopelessness, an individual could not back down from any threat, no matter how serious. Also, since economic and social circumstances limited opportunities for legitimate success, many of these men tried to find alternative ways of making money to provide for their families (similar to the innovators in Merton’s strain theory). As Trevor Noah suggested, the environment can alter what behavior is deemed acceptable.

In his research, Anderson identified two types of Black American families who resided in the inner-city: decent families and street families. Decent families embraced middle-class and mainstream norms, while street families fully embraced “street” culture, which was characterized by violence, aggression, and lawlessness. He claimed that standing against “middle-class decency” was ingrained in the code of the streets. The code, or rules and norms of the inner city, helped individuals achieve success on the streets but harmed their ability to achieve socially accepted (and legal) success (figure 6.18). This made for a difficult transition for individuals who wished to leave “the life” but lacked the skills to achieve success in a society where one does not benefit from being street-smart (figure 6.19).

Activity: Exploring Anderson’s Code of the Street

- How is the code of the streets at odds with mainstream/dominant culture?

- How do concepts discussed in the video relate to both subcultural theories and strain theories? In other words, how would each theory explain the significance of these concepts/factors?

- Based on examples provided in the video, what might contribute to racial tensions between Black community members and law enforcement in urban settings?

- How do you see girls and women represented in the code of the streets?

- Do you think that the values associated with lower-class and Black communities, according to subcultural theories, accurately reflect these communities? Do you think these communities deny middle-class/mainstream social norms?

- What are the ethical issues with researchers from mainstream or ethnocentric (white) cultures studying marginalized populations?

Gangs as Delinquent Subcultures

Frederic Thrasher, another white sociologist from the famed Chicago School, conducted a study in 1927 about gangs. He believed that the social conditions in the United States at the end of the 19th century had encouraged the development of street gangs. Like many of the other sociologists we have discussed, he was looking at the ways in which society caused crime and, in this case, encouraged people to band together.

During the 19th century, immigrants had filled the inner-city neighborhoods, creating a more culturally diverse population. They faced deteriorating housing, poor employment prospects, and a rapid turnover in the population. These conditions created neighborhoods with weak and ineffective social institutions and social control mechanisms. Thrasher believed the lack of social control encouraged youth to find alternative ways to establish social order, and they did so by forming gangs.

He described gangs as coming together spontaneously at first, then becoming bonded through conflict with other gangs and the surrounding community. What made Thrasher’s work unique from other theories with similar concepts (such as social disorganization theory and strain theories) was his identification of gangs as a subculture. Although he was the first to start down this road of studying subcultures, several other subculture scholars followed suit as they worked to understand gangs specifically and in a subcultural context.

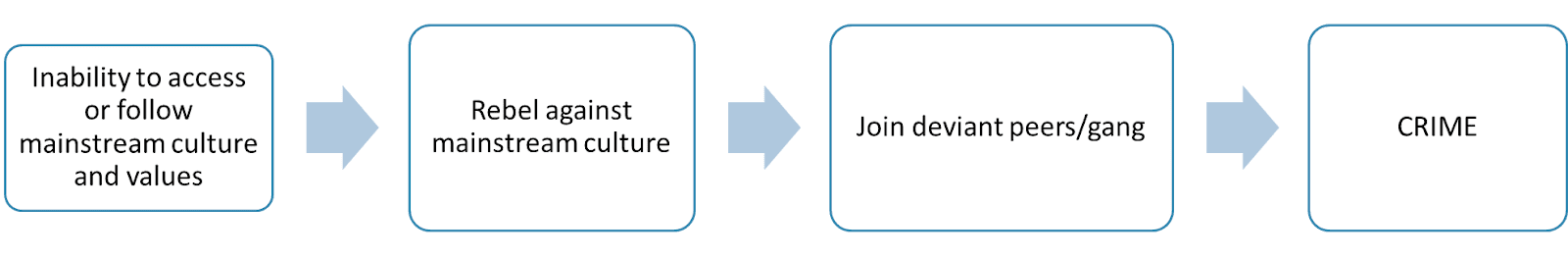

In the 1950s, Albert Cohen applied concepts from Merton’s strain theory and subcultural theories to juvenile gang formation. As with many early criminologists, Cohen saw juvenile delinquency primarily as a working-class, male phenomenon. This is because working-class youth are taught the democratic ideal that everyone can become rich and successful, but in school they encounter a set of distinctly middle-class values against which their behavior is measured. These class-specific values are framed as universal, making it much easier for middle-class youth to achieve recognition in school for behaving “correctly.” This leads to feelings of inferiority, which last as long as the working-class boys cling to that particular worldview. This strain is referred to as status frustration, for which status frustration theory is named.

According to Cohen (1955), boys experiencing status frustration may adopt attitudes and standards that defy the mainstream middle-class ideals as a way of rebelling against them and relieving the guilt of not being able to live up to them. This response is referred to as reaction formation. The delinquent subculture presents young boys with a new set of values and a means of acquiring status within a different cultural context. For example, while the middle-class places value on controlling aggression and respecting property, the culture of the gang legitimizes violence and group stealing (Cohen, 1955). While the act of theft may bring material benefits, it also reaffirms the cultural cohesion of the new group and the status of its members. It is a joint activity that derives its meaning from the common understandings and common loyalties of the group (figure 6.20).

Like Merton and Cohen, criminologists Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin (1960) researched societal goals and the ability to achieve those goals. Incorporating concepts from Sutherland’s differential association theory, they heavily emphasized the different opportunities (some more legal than others) available for juveniles to get what they want. They noticed that some neighborhoods offered more opportunities to participate in illegitimate means (like theft or selling drugs) to achieve one’s goals. Their differential opportunity theory identified three different types of gangs that would develop based on the type of neighborhood and the legal and illegal opportunities offered there.

The three gang types that can form according to differential opportunity theory are criminal gangs, conflict gangs, and retreatist gangs. Criminal gangs form in lower-class neighborhoods that already have organized criminal networks of adults who mentor the youth into crime. These illegal opportunities for achieving wealth facilitate this youth gang formation. Conflict gangs form in neighborhoods that are unstable and disorganized. Like their environment, these gangs are unorganized, and rather than engaging in organized crime for profit, members tend to use violence as a means of gaining respect within their neighborhood. This is because these neighborhoods lack legal and illegal opportunities for financial and material gain. Finally, retreatist gangs also form in areas where legal and illegal opportunities for gain are lacking. However, rather than using violence to achieve status and respect, the members simply want to escape from their reality and may engage in personal drug use to do so.

For each explanation of male youth gang formation, the theorists explored the impact of social structure, learned behavior, strain and opportunity, and/or adherence to subculture norms. Additionally, they all recognized the unique status of adolescence and how it can make people more susceptible to peer pressure or feelings of inferiority.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Subcultural Theories of Crime

Open Content, Original

“Subcultural Theories of Crime” by Jessica René Peterson, Curt Sobolewski, and Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.17. “Miller’s Cultural Deviance Theory” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.18. Subculture conformity graphic by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.20. Juvenile delinquency graphic by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Subcultural Theories of Crime Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Gangs as Delinquent Subcultures” is adapted from “Delinquency as a Subculture,” Introduction to Criminology by Dr. Sean Ashley, licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include substantially expanding and tailoring to the American context.

“Subculture” definition by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 6.19. “Street Codes — Code of the Street, Elijah Anderson” by Code of the Street, Elijah Anderson is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.