1.5 How Does a Crime Become a Crime?

It is not always clear what does and does not count as criminal behavior. In some instances, a criminal act seems obvious and makes the study of such an offense simple. Murder, for example, is a fairly obvious crime. Although there are different degrees, murder is generally a pretty clear and obvious criminal offense. What about behavior that falls in the “gray area?” The varying degrees of crime and all their complexity is another area where criminology often comes in handy.

Let’s look at an example of less obvious crimes in history: so-called “ugly laws.” In many states in the 19th and 20th centuries, it was criminal for anyone to be seen in public who was “diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object” (Chicago City Code [1881] as cited by Schweik & Wilson, n.d.). Beginning in San Francisco in 1867 and spreading across the country in the 1870s and 1880s, some ugly laws remained on the books as late as 1974 in Chicago and Omaha. These laws unfairly criminalized people with disabilities and also often targeted those of an “unfavorable” social status (Gershon, 2021). Criminologists looked at ugly laws, their sources, their intentions, and their effects, and they provided research on the harmful consequences of such laws, eventually affecting policy.

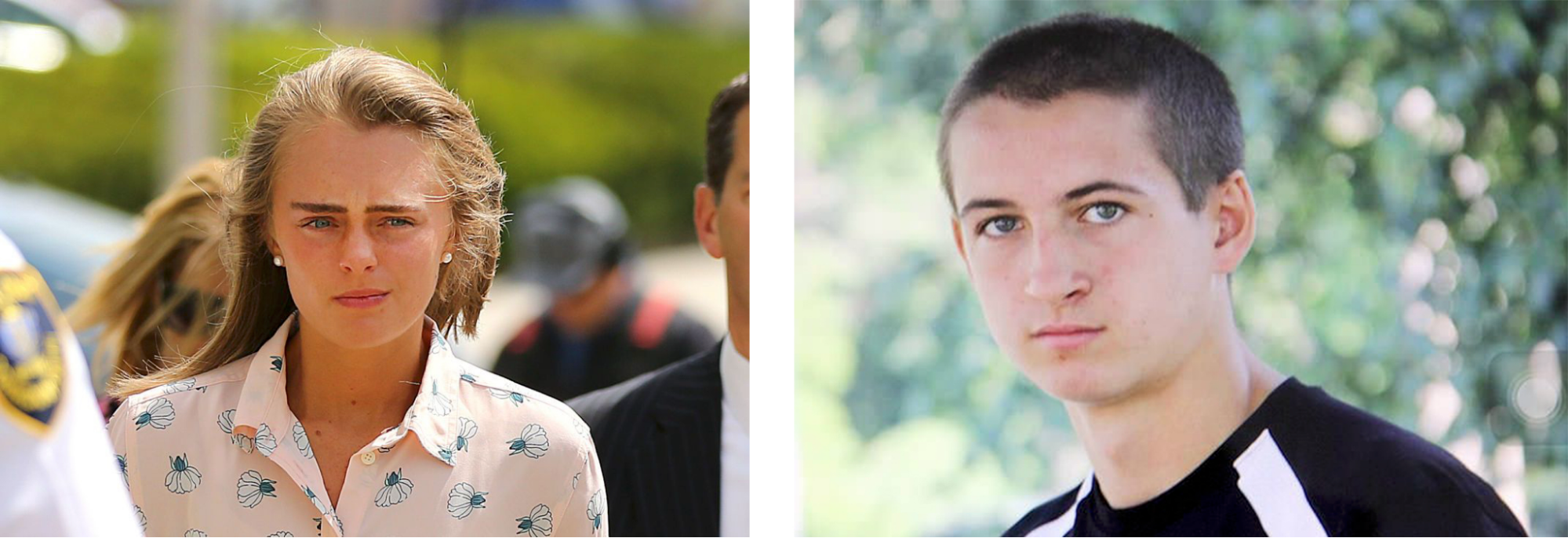

A more recent example is the determination that texting someone to encourage them to die by suicide is criminal. In 2017, Michelle Carter was convicted of manslaughter after texting her boyfriend multiple messages that pushed him to follow through with his suicidal ideation. Text records (figure 1.15) show that she brainstormed with him on the most effective, quickest, and least painful way to end his life. The most damning text message in this case was one in which she explained that she convinced her boyfriend, who had changed his mind and gotten out of the truck where he was poisoning himself with carbon monoxide, to get back in the truck and die (Commonwealth v. Carter, 2019).

Learn More: When Texting Becomes A Crime

The following transcript includes just some of the text messages exchanged between Michelle Carter and Conrad Roy after a failed suicide attempt in which Conrad claimed that he took an excessive amount of sleeping pills. All language, including typos, has been preserved in its original format. See if or when you think a legal line was crossed.

If you’re interested in the full transcripts, you can find them on this website.

Michelle Carter: I feel like such an idiot

Conrad Roy: Why

Michelle Carter: Beacuase you didn’t even do anything! You lied about this whole thing! You said you were gonna go to the woods and do it and you said things that made me feel like maybe you were actually serious, and I poured my heart out to you thinking this was gonna be the last time I talked to you. And then you tell me you took sleeping pills? Whixh first of all I know that’s a lie because you already said you wouldn’t get enough and idk how you would of got them. I’m just so confused. I thought you really wanted to die but apparently you don’t, I feel played and just stupid

Conrad Roy: Don’t I found out a new plan. and I’m gonna fo it tonight

Michelle Carter: I don’t believe you

Michelle Carter: You’re gonna have to prove me wrong because I just don’t think you really want this. You just keeps pushing it off to another night and say you’ll do it but you never do

Conrad Roy: okay

Michelle Carter: Okay what?

Conrad Roy: I’ll prove you wrong

Michelle Carter: What are you planning on doing?

Michelle Carter: Poision would work

Conrad Roy: Carbon monoxide or helium gas. I want to deprive myself of oxygen

Michelle Carter: How aware you gonna get those things?

Conrad Roy: I wish I had a gun

Michelle Carter: Would you use it?

Conrad Roy: Yes

Michelle Carter: Do you know anyone that has one?

Conrad Roy: I’m sorry I didn’t do it last night. I just took a handful of pills and went to sleep. idk I wanted to have one last good night sleep and I did

Michelle Carter: Don’t be sorry I understand that. I’m happy you got that good night of sleep. Im just still kinda in shock that you’re still here because I honestly thought you did it last night when you didn’t answer back

Conrad Roy: don’t feel like an idiot it’s gonna happen

Michelle Carter: Tonight?

Conrad Roy: Eventually

Michelle Carter: Cute 🙂 haha I love you

Michelle Carter: SEE THATS WHAT I MEAN. YOU KEEP PUSHING IT OFF! You just said you were gonna do it tonight and now you’re saying eventually….

Debates about free speech and assisted suicide raged as the courts decided that what Michelle did was, in fact, criminal and should be treated as such. Since then, other similar cases have come to light and ended in criminal charges and sentences. As a result of the precedent set by the Michelle Carter case, what may have otherwise been considered simply cruel and deranged is now considered criminal.

The Creation of Laws

The previous discussion raises the question, does society guide the laws or do the laws guide society? There is no clear answer to that complex question. When we look across the history of the United States, we can see many examples of laws and society changing one another. For example, traffic laws were created in response to the invention and proliferation of the automobile and changed the manner in which people moved from location to location in an orderly fashion (figure 1.16).

Prohibition (the banning of alcohol) in the 1920s was in response to an outcry from society about crime, corruption, social ills, and the general degradation of communities. Thirteen years later, prohibition was repealed after people realized it had missed the mark by encouraging the creation of organized crime to source and provide alcohol illegally. Drinking did not decrease, and crime merely shifted. Criminologists also study and bring to light the unintended consequences of laws like this.

Other recent examples of how changes in society have led to changes in laws include the legalization of marijuana for recreational use. Federally, the use of marijuana for any purpose is illegal, but many states (and their voters) have removed this law from their books. Societal norms around gender and sexuality have also shifted over time, and laws pertaining to the civil rights of the LGBTQIA+ community continue to change in various ways (if you want to learn more about legal changes, you can review LGBTQ Rights Timeline in American History [Website]).

Changes in specific definitions can also drastically alter what behavior counts as criminal. For example, the FBI’s definition of rape has changed significantly over the years. Before 1975, rape could not legally occur between married partners. Before 2011, penetration of body parts other than a vagina did not constitute rape, and consent was not part of the definition until 2013. How might criminologists play a role in these decisions?

Activity: Real and Ridiculous Federal and State Crimes

Read through the “ridiculous” federal and state crimes listed, and then consider the discussion questions at the end.

Ridiculous Federal Crimes

- It is a federal crime to sell “turkey ham” as “ham turkey” or with the words “turkey” and “ham” in different fonts.

- It is a federal crime in a national forest to wash a fish at a faucet if it is not a fish-washing faucet.

- It is a federal crime to knowingly let your pig enter a fenced-in area on public land where it might destroy the grass.

- It is a federal crime in any national park in Washington, D.C., to harass a golfer.

- It is a federal crime in a national park to allow your pet to make a noise that scares the wildlife.

- It is a federal crime to injure a government-owned lamp.

- It is a federal crime to sell onion rings resembling normal onion rings, but made from diced onion, without saying so.

- It is a federal crime to ride a moped into Fort Stewart without wearing long trousers.

- It is a federal crime to skydive while drunk.

- It is a federal crime to hunt doves and pigeons with a machine gun or a stupefying substance.

- It is a federal crime to take home milk from a quarantined giraffe or any animal that chews the cud.

- It is a federal crime to sell antiflatulent drugs without noting flatulence is referred to as gas.

- It is a federal crime in a national forest to say something so annoying to someone that it makes them hit you.

(FreedomWorks, 2016).

Ridiculous State Crimes

- In Wyoming, it is illegal to ski while intoxicated.

- In West Virginia, sex before marriage was illegal until 2010.

- In Washington, it is illegal to kill Bigfoot.

- In Virginia, it is illegal to hunt on Sundays.

- In Tennessee, it is illegal for anyone who has ever fought in a duel to hold public office.

- In South Carolina, up until 2016, it was illegal to seduce an unmarried woman with the promise of marriage.

- In Oklahoma, eavesdropping is illegal if what is overheard may be used to annoy others.

- In New Jersey, it is illegal to wear a bulletproof vest while committing a crime.

- In Nebraska, it is illegal to get married if you have a venereal disease.

- In Maryland, it is illegal to curse in public.

- In Louisiana, it is illegal to wrestle a bear for sport.

- In Georgia, it is illegal to eat fried chicken with a fork.

- In California, it is illegal to eat a frog that has died in a frog-jumping contest.

(Simon, 2018).

Discussion Questions

- How would a criminologist look at these laws?

- What do you think was going on that led to these laws? Do you think making these acts into crimes was the right way to address whatever was going on?

- Would you turn someone in for committing any of these crimes? Which ones? Why or why not?

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for How Does a Crime Become a Crime?

Open Content, Original

“How Does Crime Become a Crime?” by Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Jessica René Peterson.

“Learn More: When Texting Becomes a Crime” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“How Does a Crime Become a Crime? Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 1.16. “Merging traffic” by Oregon Department of Transportation is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 1.15, left. Photo (Michelle Carter) from Life and Lemons is included under fair use.

Figure 1.l5, right. Photo (Conrad Roy III) from Life and Lemons is included under fair use.