4.2 Crime in the Brain

When positivism emerged, many scientists and philosophers studied biological features, structures, and how they influence behavior. In the earliest departure from the classical school assumptions, criminologists wanted to understand how individual traits might explain why some people committed crimes and others did not. The idea that genetics, biological makeup, and the brain determined one’s criminality became a major assumption in the early and mid-1800s.

One biological explanation that found its footing at this time was the idea of moral insanity, which referred to habitual, uncontrollable criminality committed without motive or remorse. The three earliest proponents of this concept were Philippe Pinel in France, Benjamin Rush in the United States, and James Cowles Prichard in England (Rafter, 2004).

Pinel was the medical director of two asylums in France. He was interested in finding medical causes of moral insanity and was very careful about applying the scientific method as precisely as possible. In his 1801 book, Treatise on Insanity, he labeled five types of mental illness, including melancholy, dementia, idiocy, and madness with and without delirium.

Working during this same time and with similar interests was American physician Benjamin Rush. He is credited with developing a model of mental and moral functioning. In his 1812 book, Medical Inquiries and Observations, Upon the Diseases of the Mind, he described moral faculty as the ability to both distinguish between good and evil and to choose good. According to Rush, individuals suffer from either anomia, or total moral depravity, in which both the moral faculty and the conscience stopped functioning; or micronomia, a partial weakness of the moral faculty in which the individual remains aware of their wrongdoing.

James Cowles Prichard built on both of these earlier concepts in his 1835 publication, A Treatise on Insanity and Other Disorders Affecting the Mind. According to Prichard, the causes of criminal behavior and poor moral judgment are psychological and either inherited (biological) or from brain damage. In fact, he advocated for compassion and reform in the treatment of those with mental illness, including those who committed crimes.

This is a bold move away from the classical school of criminology because it indicates that the foundational concepts of deterrence will not actually prevent or stop crime. If some people are simply born or through trauma become unable to think rationally, they will not be able to weigh costs and benefits. Basically, Pinel, Rush, and Prichard believed and promoted that criminal behavior was not a decision, but was predetermined due to abnormal biology. They advocated for individualization of treatment, institutionalization, and other forms of care, not punishment.

Craniometry and Phrenology

Following the new ideas about mental capabilities came a movement to better understand the brain itself. Two scientific studies became popular: craniometry and phrenology. Craniometry is the idea that brain and skull size can tell us about one’s intelligence, behavior, and personality. Craniometrists would measure the circumference of their subjects’ skulls, or weigh the brains if they were using deceased subjects, and make determinations about who was “superior” or “inferior.” According to most craniometrists, white or Western European individuals were superior to other ethnic groups. Not only were these claims baseless and rooted in racism, but the methodology that led to such conclusions was flawed as the researchers typically knew who the brains or skulls belonged to before taking the measurements.

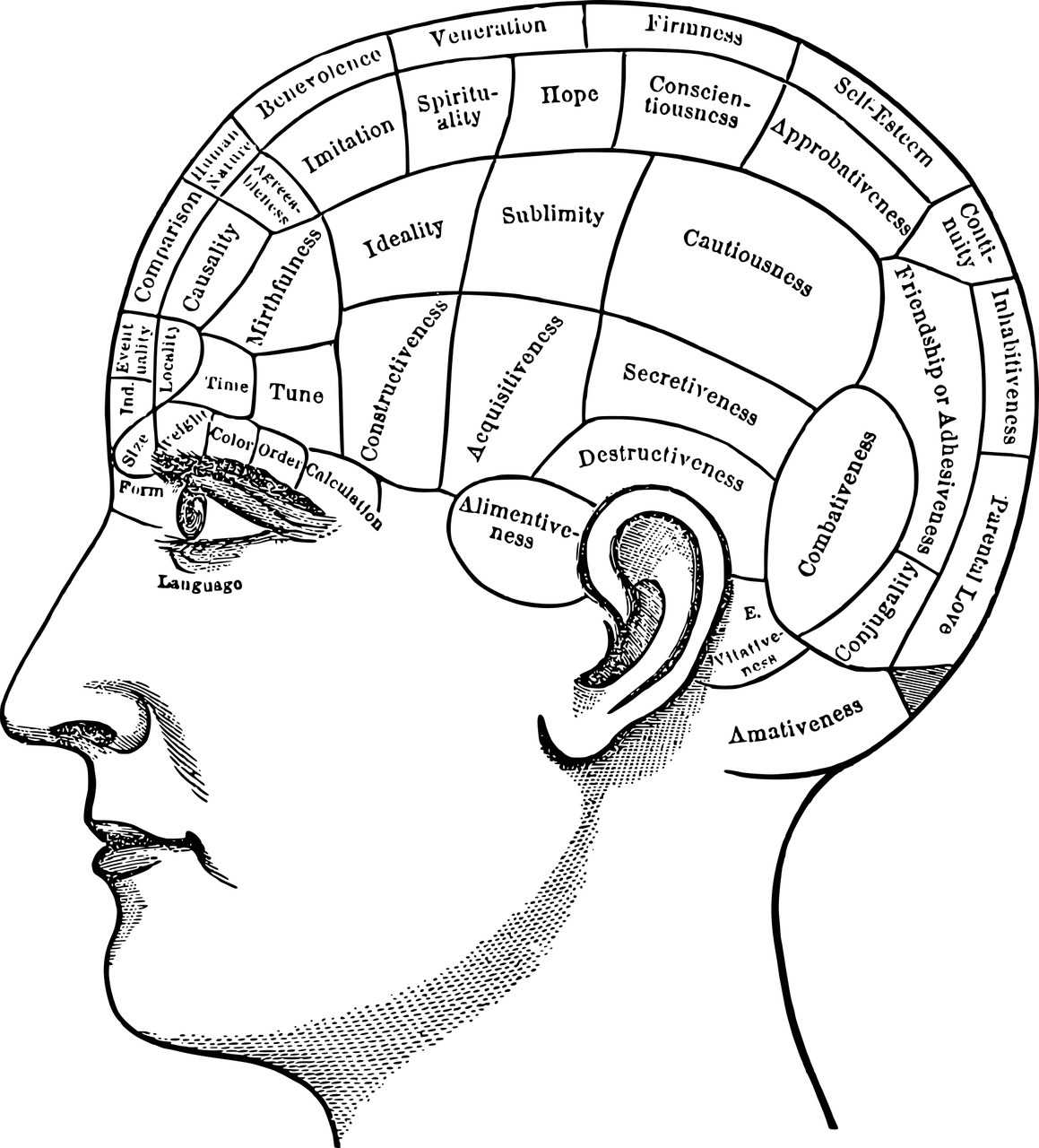

Similarly, phrenology was a theory claiming that different areas of the skull corresponded to different personality, behavioral, or mental functions (figure 4.2). Supporters believed that bumps on the skull indicated the shape of the brain underneath and the corresponding traits. Although it has been debunked and is widely regarded as pseudoscience today, phrenology was a popular idea during the first half of the 19th century.

The founder of phrenology, German researcher Franz Joseph Gall, collected skulls in the early 19th century, interviewed a variety of people from different social classes and vocations, studied and made casts of their heads, and then attempted to correlate traits with specific areas of the skull. According to his phrenology theory, criminal behavior was attributable to overdevelopment of the region of the skull responsible for “destructiveness.”

The growth of this concept can be partially explained by a Vermont railroad worker named Phineas Gage (figure 4.3). During what is easily one of the worst days at work in history, an explosion drove an iron rod into Gage’s cheek, through his brain, and out the top of his skull (Harlow, 1848). Miraculously, he lived to tell about it, but his personality and character changed. That made people, including Gall, want to find out more about the area of Gage’s brain that was pierced and why it had an effect on his behavior.

Through his research, Gall popularized the idea that criminal behavior was due to a physical abnormality or defect in the brain, not free will or anything that could be controlled. Furthermore, according to phrenology, these defects were not permanent, but instead were possible to address through treatment or self-regulation. For that reason, those believing in phrenology advocated for rehabilitation rather than punishment or deterrence. In fact, they believed brutal punishments could even make defects worse and weaken the “good” parts of the brain, like those responsible for kindness.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Crime in the Brain

Open Content, Original

“Crime in the Brain” by Mauri Matsuda and Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Crime in the Brain Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 4.2. “Physiognomy Phrenology Head” by Gordon Johnson is licensed under the Pixabay License.

Figure 4.3. “Photograph of railroad worker Phineas Gage with the railroad spike that pierced his brain” from the collection of Jack and Beverly Wilgus, and now in the Warren Anatomical Museum, Harvard Medical School, is in the Public Domain.