4.3 Crime in the Body

In the mid 1800s, the study of individuals’ facial features, known as physiognomy, became another popular way of assessing character or criminality. Unsurprisingly, and similar to craniometry and phrenology, distinctions in features among different racial and ethnic groups were deemed indicative of superiority and inferiority. The racist idea that white people were the superior race drove early attempts to find physical and biological differences that could support such claims.

In 1859, English naturalist Charles Darwin published his major work On the Origin of Species, in which he laid out his theory of evolution. He argued that all animals are descendants of a common ancestor and the diversity of species is the result of evolution, which occurred through a process of natural selection or “survival of the fittest.” In a later work, The Descent of Man (1871), among his arguments about the origins of humankind, Darwin said that virtue and vice tended to run in families. In other words, he said that moral sense was something that was likely inherited (Darwin, 1871).

Around this same time, the notion of “degeneracy,” or the idea of backward evolution (“devolution”), became popular and was used to explain not only criminality but also poverty and disability, including mental illness and physical and intellectual disabilities. This is where the term “degenerate” comes from and it continues to mean immoral and corrupt. In this argument, people with any physical, mental, or intellectual ailments and those who committed crimes were undesirable, unwelcome, and making humankind regress. Although Darwin’s work on evolution and natural selection was not specifically aimed at understanding criminality, it helped set the stage for some of the earliest and most prominent positivist theories of crime.

Learn More: Degeneracy in the Family Tree

The concept of degeneracy was promoted by several white, male, European psychiatrists and physicians who worked in asylums and prisons. In America, this concept caught on quickly with the work of Dugdale and Goddard. Richard Dugdale came out with his 1877 study of the “Jukes” family. Dugdale documented the various forms of degeneracy that supposedly proliferated across several generations of a single New York family. On the basis of his “Jukes” report, Dugdale argued for the forced sterilization of women he decided should not be allowed to have children. He also believed that degeneracy could be altered through the environment, so he promoted the notions of public welfare and education of people in lower socioeconomic classes.

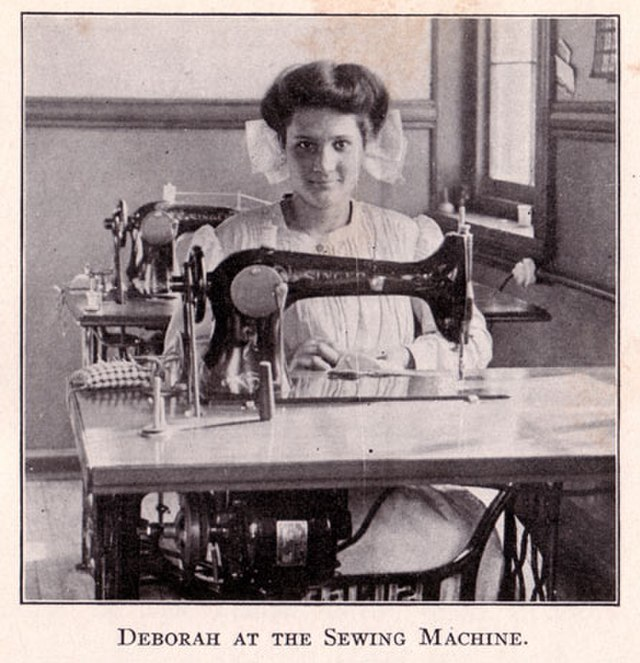

Similarly, Deborah Kallikak (figure 4.4) came to fame in 1912 when American psychologist Henry Goddard (1912) made her and generations of her family an example for his argument in favor of controlled human reproduction. He believed anyone with undesirable characteristics should not be allowed to reproduce. Goddard claimed Deborah’s family and, in fact, generations of Kallikaks had produced people who had low incomes, engaged in criminal acts, were mentally ill, and had intellectual disabilities; in other words, criminality and “inferiority” could be passed down just as eye color or hair color. He argued that, had the women in this family been stopped from having children, society could have been saved money and protected from harm.

In his book, Goddard claimed to have traced the Kallikak family back generations to determine the exact point in which the gene pool was sullied. The patriarch of this family tree, Martin Kallikak, had an affair with a barmaid. According to Goddard, the children produced with his wife were “good,” and the children produced with the barmaid were “bad,” a condition that lasted for generations (figure 4.5).

Goddard ran an institution for “feebleminded” children. Feebleminded, an outdated term that is now recognized as offensive, was used to describe those with intellectual disabilities, learning disabilities, and mental illness. It was there he supposedly studied Deborah Kallikak, the great-great-great granddaughter of Martin and the barmaid. He allegedly traced the family tree to find that the descendants of Martin and his wife were intelligent, morally upstanding, successful members of the community. In contrast, Goddard claimed that those who descended from the tryst with the barmaid were morally repugnant criminals or, at best, a drain on society. His book was a huge success and was used worldwide to justify the forced sterilization or murder of those determined to be undesirable. His legacy is deeply intertwined with Nazi genocide and the American eugenics movement, which we’ll discuss later in this chapter.

Lombroso and Born Criminals

In the late 1800s, Cesare Lombroso’s work was taking Europe by storm. He is most closely associated with the origins of the positive school of criminology and is considered one of the earliest theorists to use the scientific method to study crime (Rafter, 2009). Unfortunately, the work he produced and the harm he caused with both his research practices and conclusions far overshadow any legitimate contributions he made to science.

Lombroso was a doctor employed by the Italian military, and he worked in asylum and prison institutions (Rafter, 2006). There, he conducted autopsies on people convicted of crimes. He documented and compared the physical characteristics of criminals and noncriminals by comparing the bodies of people who had been convicted of crimes to those in the Italian military. In his book The Criminal Man, Lombroso (1876) argued that criminals were distinct from noncriminals due to pathology, or abnormal physical and psychological characteristics.

Influenced by Darwin and the earlier proponents of “degeneracy,” Lombroso theorized that criminals suffered from a pathology known as atavism. According to Lombroso, an atavist was someone who was less evolved than the rest of society, and people who commit crimes were the most primitive among us. He described the most atavistic humans as sharing physical features, such as bulky jaw bones, small heads, prominent brows, darker skin, or larger ears. Essentially, he viewed any features that deviated from what he deemed the norm as stigmata that could indicate one’s atavism. In later years, Lombroso expanded this to include characteristics such as having tattoos, lacking remorse, or having a family history of epilepsy. In other words, Lombroso defined stigmata as physical, psychological, and functional anomalies (figure 4.6.; Ferrero, 1911; Mazzarello, 2011).

Lombroso believed that people who chronically engaged in criminal offending and had a collection of these stigmata were stuck in an earlier stage of evolution and were unable to change or stop offending. He referred to these individuals as born criminals and advocated for their incapacitation so they could not commit crimes or reproduce. In extreme cases, Lombroso even argued in favor of their deaths, but for those who had less severe physical abnormalities, he believed there was a chance of rehabilitation. Criminaloids, as he referred to them, were similar to “normal” people, and their criminality could be explained by a variety of factors, such as disease or environment (DeLisi, 2012; Rafter, 2006). Lombroso updated his theory over the course of five editions of his book, which was published in Italy between 1876 and 1897 and was very influential across Europe and in the United States.

Lombroso’s work has been widely criticized for several reasons. First, some of the physical characteristics that were said to distinguish born criminals from noncriminals could be explained by environment (e.g., poor nutrition) rather than heredity. Second, many of the physical characteristics Lombroso identified as physical stigmata were characteristics common in marginalized racial or ethnic groups. Third, subsequent research refuted many aspects of Lombroso’s theory. Nonetheless, his work became foundational to the positivist approach to criminology.

Sheldon and Somatotyping

Adding to the discussion of bodies and crime, American psychologist William Herbert Sheldon believed someone’s personality—and, therefore, criminality—could be identified by their body type. This theory is called somatotyping, and Sheldon made it somewhat popular in the 1940s and 1950s. He thought that body types and their corresponding characteristics were genetic and related to the way tissue layers developed. Based on the focused development of one’s endoderm (the first layer of tissue, which includes the internal organs), mesoderm (the middle layer of tissue, which includes muscles and bones), and ectoderm (the outer layer of tissue, which includes the skin and nervous system sensors), Sheldon (1954) believed one of the following three body types would result (figure 4.7):

- The ectomorph body build (thin, lean, delicate) was associated with an intellectual, introverted personality. He thought these people would be neurotic, artistic, and shy.

- The mesomorph body build (compact, athletic, muscular) was associated with an aggressive, extroverted personality. He thought these people would be competitive, risk-taking, and adventurous.

- The endomorph body build (soft, round, overweight/obese) was associated with a sociable, easy-going personality. He thought these people would be funny, lazy, and affectionate.

According to Sheldon, mesomorphs had the highest likelihood of being criminals. To test his theory, he assessed thousands of photos of nude male college students and sorted them into categories based on 17 different body measurements (Sheldon et al., 1940). He created a scoring system that would produce a three-number scale to indicate the amount of endomorphy, mesomorphy, and ectomorphy that was present in a person. According to Sheldon, a “bad” body was proof of a bad personality, and society should prevent bad bodies from producing more bad bodies.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Crime in the Body

Open Content, Original

“Crime in the Body” by Mauri Matsuda and Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Crime in the Body Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 4.4. “Kallikaks deborah2” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 4.5. “Kallikak Family caricature” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 4.6. “Plate 6 of Cesar Lombroso’s L’Homme Criminel” is in the Public Domain, courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Figure 4.7. “Bodytypes” by Granito diaz is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.