4.4 Crime in the Mind

Psychologists have contributed to the field of criminology by trying to figure out how personality traits, patterns in thinking, the subconscious mind, and mental illnesses or disorders may contribute to criminal behavior. Some psychological theories imply that humans lack agency, meaning that our behavior is out of our own control to a degree, while others point to predispositions toward certain behaviors that may lead to criminality. As you will see in later chapters, concepts and research from the field of psychology have influenced and been integrated into many theories of criminal offending.

It is difficult to talk about criminality or “abnormality” in the field of psychology without first mentioning Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud. He developed psychodynamic theories that use psychoanalysis to explain human behavior. Psychodynamic theories are formed around the following basic assumptions:

- Unconscious motives drive our feelings and behavior.

- Our feelings and behaviors as adults are rooted in our childhood experiences.

- We have no control over our feelings and behaviors since they are all caused by our unconscious, which we cannot see.

- Personality is made up of the id (primitive and instinctive), ego (decision-making), and superego (learned values and morals).

Psychoanalysis examines one’s childhood and tries to better understand their unconscious mind and motivations. According to Freud, the unconscious is where unpleasant memories and explosive emotions accumulate as repressed memories and emotions. In other words, what happened to us in the past can guide our behavior, even if we are not aware of the connection. In order to help someone change their behavior, Freud thought it was essential to access and understand their repressed memories via psychoanalysis. According to Freud, individuals are not aware of what determines their behavior. This is in contrast with the concept of “free will” that was part of the classical criminological theories discussed in Chapter 3.

German-British psychologist Hans Eysenck (1967) combined the study of behavior, biology, and personality to explain criminality, and formed the criminal personality theory. He suggested that certain inherited characteristics make crime more likely, but he did not believe that criminality itself is an inherited trait. Eysenck argued that behavior and personality traits can be either learned (conditioned) or genetic (inherited). He believed that psychoticism, extraversion, and neuroticism are important personality traits in relation to crime and how we control it. Neurotic extroverts are people who require high stimulation levels from their environments and whose sympathetic nervous systems respond quickly to stimuli. Psychotic extroverts are described as cruel, insensitive to others, and unemotional. Most of Eysenck’s work has since been rejected, but that did not stop his influence on the work of others.

Bandura and Criminal Modeling

The idea that criminal behavior can be learned is important to many theories, many of which will be discussed in Chapter 6 since they heavily emphasize social interactions in the learning process. However, at the core of all learning theories are the mechanisms by which we learn. We will start here with one of the first theorists to see a direct link between observation and aggressive behavior.

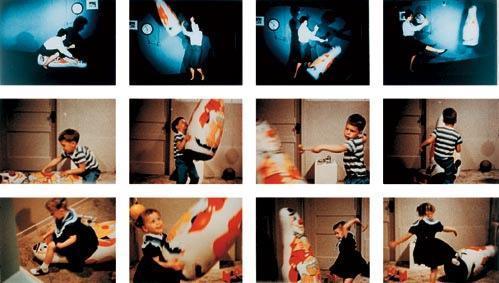

Canadian-American psychologist Albert Bandura studied learning and centered his research on the learning of aggression. His famous Bobo doll study (figure 4.8) in the 1960s involved children first watching an adult attack a plastic clown punching bag named “Bobo.” The children were then placed in a room with the Bobo doll where they copied the behavior, even using the same tools and words in their attacks. This study illustrated that people are capable of learning by simply watching others and observing the results of their actions. Bandura called this observational learning, or modeling. Later variations on his Bobo doll study led him to clarify the modeling process as involving attention to the model (e.g., the person modeling the behavior), retention of what was learned, motivation to imitate what was learned, and reproduction of the learned behavior (Bandura, 1977). This is just one mode of learning. We will discuss others and how they relate to crime theory in Chapter 6 alongside the theories they heavily influenced.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Crime in the Mind

Open Content, Original

“Crime in the Mind” by Curt Sobolewski, Taryn VanderPyl, and Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Crime in the Mind Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Bandura and Criminal Modeling” is adapted from “Learning,” Psychology 2e, Openstax, by Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include expanding and adapting to a criminological context.

Figure 4.8. “Bobo Doll Deneyi” by Okhanm is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.