5.3 The Chicago School

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Chicago was one of the fastest-growing cities as it experienced a huge influx of people, especially immigrants from various foreign nations. Throughout the 1900s, sociologists at the University of Chicago were witness to the interplay among different groups. So many theories came out of the University of Chicago during the 20th century that they became known collectively as The Chicago School. The Chicago School focused on urban settings, bringing to the forefront many new theories that centered urban America.

Robert E. Park, an American urban sociologist, spent his professional career studying human behavior as it pertained to human ecology, race relations, assimilation, migratory patterns, and social structure. Along with his colleagues, noted sociologists Ernest W. Burgess, and R. D. McKenzie, he published the book The City (1925). In it, they liken a city to a living organism, with interactions between humans and their natural environments acting in both a shared and conflicting manner, depending on a group’s location within the city.

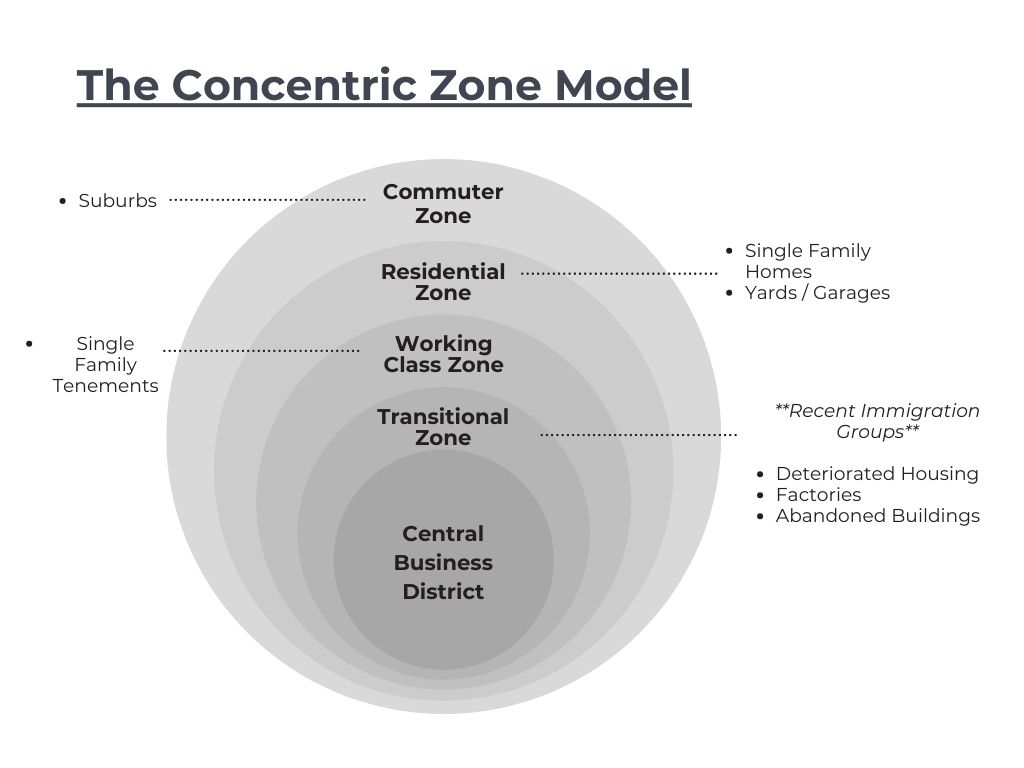

It was Burgess, however, who proposed the concentric zone theory, which states that a city’s design is conducive to criminal behavior within its zone of transition, which is the space between the areas where people work and where they live. In simpler terms, a city can be seen much like a target board, with multiple concentric circles surrounding a central hub (figure 5.10). Each circle is specific to its municipal function (manufacturing, city business, residential, etc.).

Shaw and McKay’s Social Disorganization Theory

In the 1940s, sociologists Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay took what they had learned as students of Park and Burgess and developed their own theory. They began to plot the addresses of juvenile court-referred boys and noticed that many of the addresses were located in the zone of transition (zone 2). Upon further investigation, Shaw and McKay noticed three qualitative differences in the transitional zone compared to other zones. First, the physical status included the invasion of industry and the largest number of condemned buildings. When many buildings are in disrepair, population levels decrease. Second, the population composition was also different. The zone in transition had higher concentrations of foreign-born and Black heads of families. It also had a transient population. Third, there were socioeconomic differences. The transitional zone had the highest rates of welfare, the lowest median rent, and the lowest percentage of family-owned houses. Interrelated, the zone also had the highest rates of infant deaths, tuberculosis, and mental illness.

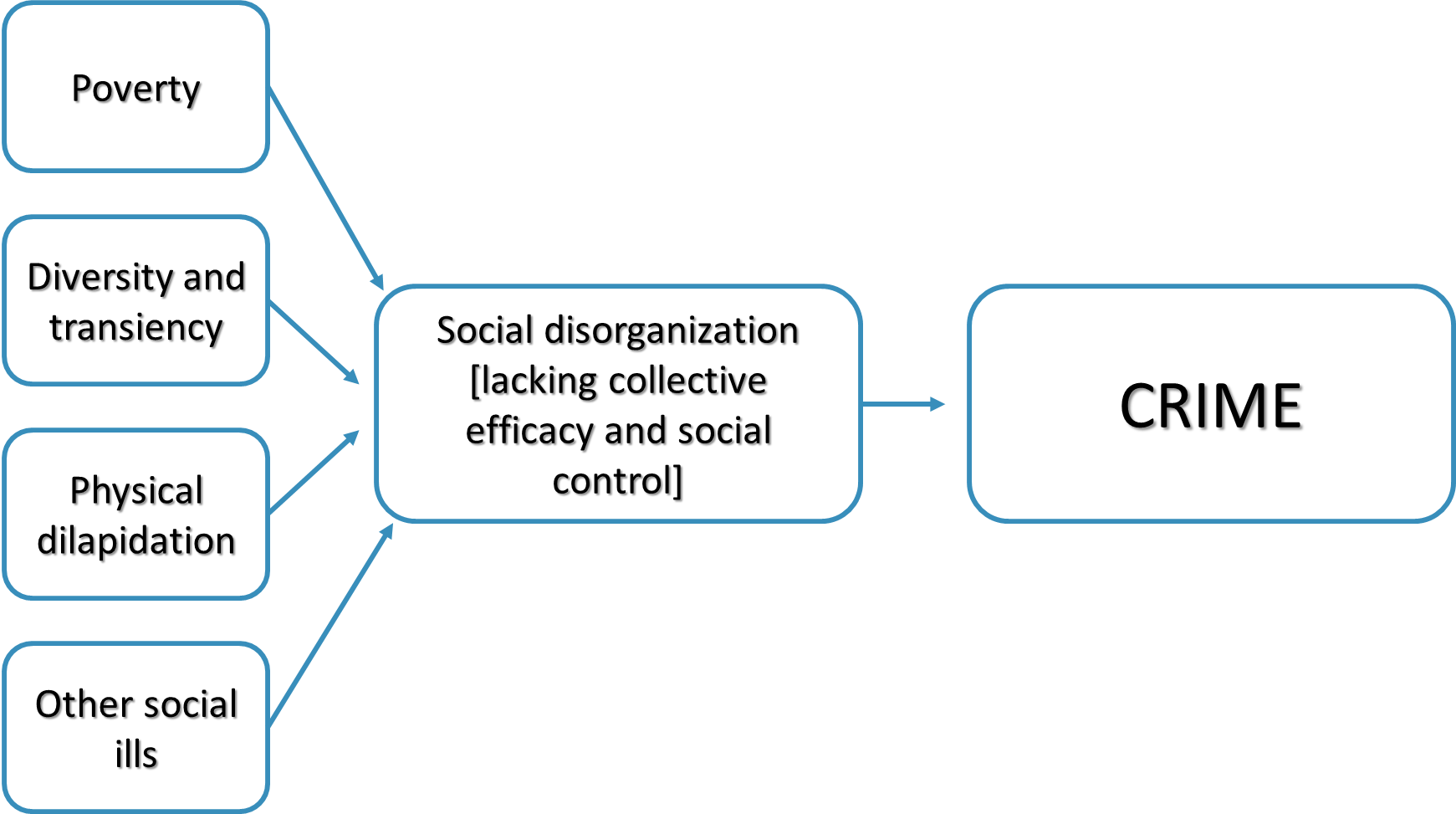

Shaw and McKay believed the zone in transition led to social disorganization. Social disorganization is the inability of social institutions to control individuals’ behavior. Consequently, their theory, social disorganization theory, claims that neighborhoods with weak community controls caused by poverty, residential mobility, and ethnic heterogeneity will experience a higher level of criminal and delinquent behavior. Since the zone in transition had people moving in and out at such high rates, social institutions (like family, school, religion, government, economy) and community members could no longer agree on essential norms and values. As earlier stated, many residents were from different countries. Speaking different languages and having different religious beliefs may have prevented neighbors from talking to one another and solidifying community bonds. As described by Durkheim, socially disorganized communities lack a collective conscience as well as the ability to mobilize their social networks against crime, also known as collective efficacy (Sampson et al., 1997).

Overall, Shaw and McKay concluded that crime and delinquency were the result of lacking economic opportunities and the breakdown of social control in families, neighborhoods, and communities (figure 5.11). They were two of the first theorists to put forth the premise that community characteristics matter when discussing criminal behavior. Rather than seeing criminal behavior as coming from dangerous people, they saw it as coming from dangerous places, regardless of the specific individuals who live there.

Learn More: Does Social Disorganization Theory Work Outside of the City?

Historically, crime rates have been lower overall in rural communities than in urban metropolitan areas (figure 5.12). Relying on social disorganization theory’s conceptual origins, there is a tendency to assume that urban communities are “disorganized” and rural communities are “organized.” In fact, this theory has been used to help explain the difference in crime rates between urban and rural areas. Initially and intuitively it makes sense that small towns, where everyone knows each other, would have shared beliefs, higher levels of collective efficacy, and perhaps better social control over unwanted and criminal behavior. However, a deeper dive exposes problematic assumptions, methodological issues, and many other considerations that have to be addressed when making such a comparison.

First, rural areas have long been painted as simple, peaceful, and without crime. While there are surely elements of this in the countryside, the assumption that crime just doesn’t happen in rural areas is inaccurate and has been harmful to the study of rural areas. Rural communities have been largely excluded from criminological research. Theories have been primarily based on urban populations, limiting their ability to explain crime in non-urban spaces. For example, neighborhoods and streets have often been used as units of measurement when testing social disorganization theory, but do we see the same type of community organization in rural areas where many acres may separate homes?

Research aimed at testing social disorganization theory picked up in the 1960s and has remained pretty consistent since then. Researchers have found that many components of social disorganization theory, such as residential stability and home ownership, social network cohesion, poverty, and family disruption, can indeed be applied to crime in rural areas (Bouffard & Muftic, 2006; Lee, 2008; Moore & Sween, 2015). Other researchers, such as Kaylen and Pridemore (2013), found support for the link between disorganization and crime, but they concluded that the factors causing disorganization in rural settings differ from those that are traditionally thought to produce disorder in an urban context.

Critics of social disorganization theory highlight definition issues with the term “disorganization” and argue that communities that are traditionally deemed to be disorganized may still be organized—just in ways that oppose broader societal norms (Harkness et al., 2022). In other words, some communities and cultures may actually embrace certain types of crime or accept violence under certain circumstances. For example, a perceived threat to one’s masculinity in a highly patriarchal community might lead to violence that the community views as acceptable. Or, a community that financially thrives off a locally organized drug distribution operation may choose to protect and facilitate that behavior. In other words, high collective efficacy in a community does not always result in the absence of criminal behavior.

Taken together, applying social disorganization theory to rural areas brings us back to the original idea that place matters in understanding crime.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for The Chicago School

Open Content, Original

“Learn More: Does Social Disorganization Theory Work Outside of the City?” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.10. “The Concentric Zone Model” by Jessica René Peterson and Mindy Khamvongsa, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.11. “Diagram of Shaw and McKay’s Social Disorganization Theory” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“The Chicago School Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“The Chicago School” is adapted from “The Chicago School of Criminological Theory,” Introduction to Criminal Justice by Brandon Hamann, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include shortening and adding initial context.

“Shaw and McKay’s Social Disorganization Theory” is adapted from “The Chicago School,” Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Brian Fedorek, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include expanding and rewriting.

Figure 5.12. “Nursery with red buildings in rural Washington County, Oregon” by M.O. Stevens is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.