6.2 Crime as Learned Behavior

Learning is a key component of many criminological theories. The field of psychology provides explanations for mechanisms of human learning that have been adopted by criminologists attempting to understand criminal offending behavior. Additionally, some theories, categorized as interactionist theories, suggest that criminal behavior is learned through our interactions with others. These explanations emphasize group membership (such as belonging to a clique like the “plastics,” “geeks,” or “jocks” at school) and relationships in the socialization process. The learning process is especially important in theories that address behavior, gang development, and crime among youth.

One of the first theorists to associate crime with learning was Gabriel Tarde. He was a French sociologist and criminologist who tried to figure out how people became criminally involved. In his book The Laws of Imitation, Tarde (1903) argues that people do what they know, which he calls the theory of imitation. According to the theory of imitation, people who commit crimes are simply modeling the deviant behaviors they see around them. When it was published, this theory contradicted the commonly held belief that people who broke the law were simply bad people. Tarde’s theory was an important idea because it suggested that if criminal behavior was learned (imitated), then it could also be unlearned.

According to Tarde, imitation is the source of all progress that occurs, both good and bad. Tarde said people are influenced by those they have a close relationship with or at least by those they observe regularly, such as family members, neighbors, friends, and teachers. For this reason, Tarde named close contact as the first of his three laws of imitation.

The second law concerns the imitation of superiors by inferiors. Tarde said people are influenced by those who have power or are in positions of power. The person in the inferior position (such as a child, employee, or the new kid in school) may want to see themselves as “superior” and might imitate the behaviors and attitudes they see in those who hold power (such as their parents, boss, or the cool kid in school).

The third and final law of imitation is insertion. This means that the new behaviors that were learned through imitation replace the person’s old behaviors. Tarde believed people would observe someone else, want to be more like them, copy their behaviors, then adapt the behaviors to make them their own. In other words, the new behavior is customized and personalized as it replaces the old behavior.

Tarde’s ideas might sound familiar if you recall our discussion in Chapter 4 of Bandura’s Bobo doll experiments. Bandura’s work was much later than Tarde’s theorizing and used experimentation to support the idea that violent behavior could be learned and modeled. He saw family members, others in one’s subculture, and models provided by the mass media as primary teachers in observational learning. Even though research has never produced a direct link between violence on television and long-term violent behavior in individuals, Bandura was a frequent critic of the violence that appeared on television and in movies. His belief was that among individuals who are already aggressive, observing aggression will influence future aggressive behavior.

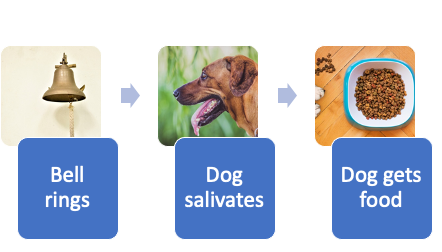

How exactly is this link between observation and behavior formed? If watching a television show or playing a video game is not enough to directly cause similar behavior, then how strong is the learned portion of criminal offending? Two scientists—one a physiologist and one a psychology student—discovered key aspects of learned behavior by studying animals. In the late 19th century, Ivan Pavlov was trying to study digestion in dogs when he noticed that the dogs’ reactions to food were changing over time. Based on his observations, he set up an experiment in which he would ring a bell before feeding the dogs. He noted that eventually, the dogs began salivating in anticipation of their food when they heard the bell (figure 6.2). This experiment illustrates the process of classical conditioning in which an automatic conditioned response is paired with a stimulus.

Classical conditioning relies on the idea that certain responses are natural and do not require learning. For example, dogs will salivate or get excited when they see and smell food (unconditioned stimulus). However, Pavlov discovered that these natural responses can be manipulated. He got dogs to salivate in response to a neutral stimulus (the ringing of a bell) that on its own elicited no response from the dogs. In other words, the bell was just a bell until Pavlov followed it with food. Once the dogs learned to associate it with food, they would salivate at the sound of the bell (conditioned response). He repeated this over and over again so that the dogs eventually started to salivate at the sound of the bell even when food was not present. We can see a similar response by Dwight in the hit show, The Office (figure 6.3).

B.F. Skinner took the basics of Pavlov’s experiment of connecting a neutral stimulus (the bell) to positive reinforcement (the food) and expanded upon these ideas through experimentation on rats and pigeons. He saw that classical conditioning was limited to existing behaviors that are reflexively elicited and that it did not account for new behaviors. He saw behavior as being motivated by the consequences we receive for the behavior: the reinforcements and punishments. In other words, if a person or animal does something that brings about a desired result, they are more likely to do it again. If they do something that does not bring about a desired result, they are less likely to do it again. Skinner was describing operant conditioning.

In operant conditioning, the reinforcements and punishments for behavior can be positive or negative. Positive and negative do not mean good and bad. Instead, positive means you are adding something, and negative means you are taking something away. Reinforcement means you are increasing a behavior, and punishment means you are decreasing a behavior. Reinforcement can be positive or negative, and punishment can also be positive or negative. All reinforcers (positive or negative) increase the likelihood of a behavioral response. All punishers (positive or negative) decrease the likelihood of a behavioral response. Now let’s combine these four terms: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment (figure 6.4).

| Reinforcement | Punishment | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Something is added to increase the likelihood of a behavior (getting a reward). For example, a child is given a piece of candy when they clean their room. | Something is added to decrease the likelihood of a behavior (getting something bad). For example, a student is scolded for texting in class and stops as a result. |

| Negative | Something is removed to increase the likelihood of a behavior (something bad is removed). For example, your car stops beeping when you put on your seatbelt. | Something is removed to decrease the likelihood of a behavior (taking away something good). For example, a parent takes away a child’s favorite toy, so the child stops whining. |

Studies have shown that behavioral conditioning is rarely this straightforward and can easily backfire. For example, research has shown that spanking can increase aggressive behavior and that the more a parent spanks a child, the more likely the child is to defy the parent (Gershoff et al., 2016). Antisocial behavior and aggression have been linked to excessive use of positive punishment. This type of punishment may also contribute to cognitive and mental health problems. It can teach avoidance behavior and, for many, create a goal of simply avoiding punishment rather than learning the intended behavior. For further clarification on the difference between types of conditioning, the video in figure 6.5 is a great resource.

The learning and interactionist theories discussed in the following sections of this chapter all assume that criminal behavior is learned from others through interaction. They incorporate psychological understandings of the learning process and behavioral conditioning, as previously discussed, into their assumptions. More specifically, these theories assume that criminal behavior is transmitted between groups and generations, and they emphasize the importance of the relationship between “learner” and “teacher” or reinforcements and punishments. Let’s start with differential association theory and social learning theory to see how all of this comes together.

Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory

Now recognized as one of the most important criminologists of the 20th century, Edwin H. Sutherland (1947), developed differential association theory. Sutherland aimed to establish an individual-level sociological theory of crime that refuted claims that criminality was inherited. Sutherland explored the role of the immediate social environment, which was often discounted in broader macro-level theories, and suggested that behavior was primarily learned within small group settings. Importantly, Sutherland sought to articulate a formal theory by presenting propositions that could be used to explain how individuals come to engage in crime. In his Principles of Criminology textbook, Sutherland articulated the following nine propositions:

- Criminal behavior is learned. Stated differently, people are not born criminals. Experience and social interactions inform whether individuals engage in crime.

- Criminal behavior is learned in interaction with other persons in the process of communication. This communication is inclusive of both direct and indirect forms of expression.

- The principal part of the learning of criminal behavior occurs within intimate personal groups. The important and key people in your social life are where such learning processes occur.

- When criminal behavior is learned, the learning includes (a) techniques of committing the crime, which are sometimes very complicated, sometimes very simple; (b) the specific direction of motives, drives, rationalizations, and attitudes. The learning process involves both instruction on how to commit crimes and why they might be committed.

- The specific direction of motives and drives is learned from definitions of the legal codes as favorable or unfavorable. Definitions encompass an individual’s attitude toward the law. Attitudes toward the legality of crimes, deviance, or antisocial behavior can vary.

- A person becomes delinquent because of an excess of definitions favorable to violation of law over definitions unfavorable to violation of law. The balance of exposure to definitions favorable or unfavorable to the law is the primary determinant of whether an individual will engage in crime. If exposed to more definitions that are unfavorable to the law, individuals will be more likely to engage in crime.

- Differential associations may vary in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity. Not all associations (or interactions) are created equal. How often one interacts with a peer, how much time one spends with a peer, how long someone has known a peer, and how much prestige we attach to certain peers determines the strength of a particular association.

- The process of learning criminal behavior by association with criminal and anti-criminal patterns involves all of the mechanisms that are involved in any other learning. Learning is a process not specific to crime but to all behavior. Thus, the mechanisms through which we learn how to behave at work or in our families are the same general mechanisms that impact how we learn crime.

- While criminal behavior is an expression of general needs and values, it is not explained by those general needs and values, since non-criminal behavior is an expression of the same needs and values. Behaviors can have the same end goal. However, the means to obtain this goal can vary. Selling drugs or working at a retail store may both reflect the need to earn money; thus, we cannot separate delinquent or non-delinquent acts by different goals. Other factors (e.g., the balance of definitions one is exposed to) determine whether or not a person engages in a specific behavior (Sutherland & Cressey, 1978 p. 80-83; italics specify text as originally written and we have used bold text to emphasize important points).

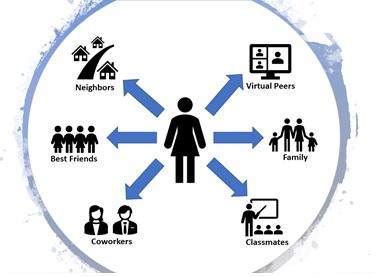

The primary component of the theory is the role of differential association(s). Individuals have a vast array of social contacts and intimate personal groups with whom they interact. Figure 6.6 depicts some examples of sources of social influence, including friends, family, siblings, neighbors, and co-workers. All of these people serve as sources of social influence, but the extent of their influence depends on the factors that characterize the interactions (e.g., frequency, duration, priority, and intensity). Not all peers/associates have the same level of influence. Consider your own social world. Who do you spend the most time with, trust more, look to regularly for help? These individuals comprise your intimate personal group that facilitates the definitions you might have regarding deviant or prosocial behavior. For instance, an individual whose friends are extremely important to them and that they have known for multiple years would be anticipated to have a greater degree of influence on that individual’s behavior than would a new acquaintance from class or work. Overall, research demonstrates that affiliation with delinquent peers can explain the initiation, persistence, frequency, type of offending, and desistance (Elliott & Menard, 1996; Fergusson & Horwood, 1996; Matsueda & Anderson, 1998; Thomas, 2015; Warr, 1993, 1998).

The effect of affiliation with deviant peers on criminal outcomes is attributable in part to how these sources of social influence inform the degree of definitions that are favorable or unfavorable toward the law. Although Sutherland did not clearly operationalize the concept of definitions at the time, it is generally understood that definitions reflect the attitudes favorable to crime that enable individuals to approve or rationalize behavior across situations (Akers, 1998). For example, definitions, or ideas, that are favorable to crime include “drinking and driving is fine” or “don’t get mad, get even.” Definitions that are not favorable to crime include “play fair” or “I must rise above insults and ignore them.” Individuals who internalize and accept definitions that are more favorable to crime will be more likely to actively participate in criminal behavior (figure 6.7).

At its core, differential association theory relies on the basic assumptions of classical conditioning that people learn to associate stimuli with certain responses over time. When Sutherland was theorizing about crime, the public generally saw people who committed crimes as abnormal. To Sutherland, criminal behavior was not about free-willed choice or abnormality but occurred due to what one learned from their close peers. His proposal that anyone could become a criminal through normal learning mechanisms was quite shocking.

Burgess and Akers’ Social Learning Theory

While Sutherland (1947) developed one of the most well-known theories, one limitation was his description of precisely how learning occurred. In the eighth proposition of differential association theory, Sutherland (1947) states that all the mechanisms of learning play a role in learning criminal behavior. This suggests that the acquisition of criminal behavior involves more than the simple imitation of observable criminal behavior, but Sutherland does not fully explain exactly how definitions from associates facilitate criminal behavior. Robert Burgess and Ronald Akers (1966) reformulated the propositions developed by Sutherland into what was initially called differential reinforcement theory. Akers (1998) eventually modified differential reinforcement theory into its final form, social learning theory.

Social learning theory is composed of four main components: 1) differential associations, 2) definitions, 3) differential reinforcement, and 4) imitation. The first two components are nearly identical to those observed in differential association theory. Differential association was expanded to include both direct interactions with others who engage in criminal acts and more indirect associations that expose individuals to various norms or values. For example, friends of friends who may not directly interact with an individual still exert indirect influence through the reinforcing behaviors and definitions of a directly tied friend. Definitions were similarly described as the attitudes or meanings attributed to behaviors and can be both general and specific. General definitions reflect broad moral, religious, or other conventional values related to the favorability of committing a crime, whereas specific definitions contextualize or provide additional details surrounding one’s view of acts of crime. For example, a general definition of crime may reflect an individual’s belief that they should never hurt someone else, but the use of substances is acceptable because it does not harm anyone else. Recent efforts have also underscored that attitudes toward crime can be even more specific and depend on situational characteristics of the act (Thomas, 2018, 2019). For instance, an individual may hold the general definition that they should never fight someone. However, they may adopt a specific definition that suggests that if someone insulted their family or started the conflict, then perhaps fighting is acceptable.

Borrowing from principles of operant conditioning, Burgess and Akers (1966) argued that differential reinforcements are the driver of whether individuals engage in crime. This concept refers to the idea that an individual’s past, present, and anticipated future rewards and punishments for actions explain crime. If an individual experiences or anticipates that certain behaviors will result in positive benefits or occur without consequences, the likelihood that the behavior will occur will increase (figure 6.8). This process is comprised of four types of reinforcements or punishments:

- positive reinforcement: reinforcements that reward behavior, such as money, status from friends, and good feelings, will increase the likelihood that an action will be taken

- positive punishment: a negative or aversive consequence, such as getting arrested, injured, or caught, that occurs after a behavior is exhibited decreases the likelihood it will happen again

- negative reinforcement: reinforcements that help a person avoid the negative consequences of a behavior, such as avoiding getting caught, arrested, or facing disappointment from others, and increase the likelihood that an action will be taken

- negative punishment: the removal of a positive reinforcement or stimulus after an undesired behavior occurs to decrease the likelihood a person will engage in the behavior again; for instance, if a child gets into a fight with a friend, their parent may take away their cell phone, cut off their Netflix access, or remove other privileges.

Lastly, imitation, the mimicking of a behavior after observing others doing it, is often what facilitates the initiation of behavior. Once the behavior has been engaged in, imitation plays less of a role in the maintenance of or desistance from that behavior.

You can think of social learning theory as the combination of differential association theory with the concepts of operant conditioning. While differential association theory does not address how learning happens, social learning theory does. It emphasizes the importance of reinforcements and punishments to the learning process for crime and other behaviors.

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Crime as Learned Behavior

Open Content, Original

Figure 6.2. “Pavlov Dog Reaction” by Curt Sobolewski and Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0. It is adapted from the following images, all licensed under the Unsplash License: “a bell hanging on a wall with a rope” by rhoda alex; “close up photography of brown dog with tongue out” by Mpho Mojapelo; “brown peanuts in blue plastic bowl” by Mathew Coulton.

Figure 6.7. “Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.8. “Burgess and Aker’s Social Learning Theory” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Crime as Learned Behavior Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Crime as Learned Behavior” is adapted from “Operant Conditioning,” Psychology 2e, Openstax, by Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, Curt Sobolewski, and Taryn VanderPyl, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include expanding and adapting to a criminological context.

“Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory” is adapted from “Differential Association Theory” Introduction to Criminology by Dr. Zachary Rowan and Michaela McGuire, M.A. is licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include providing an example and a summary transition paragraph.

“Burgess and Akers’ Social Learning Theory” is adapted from “Social Learning Theory” Introduction to Criminology by Dr. Zachary Rowan and Michaela McGuire, M.A. is licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include providing a summary transition paragraph.

Figure 6.4. Table is adapted from”Positive and Negative Reinforcement and Punishment” by Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett in “6.3 Operant Conditioning“, Introduction to Psychology 2e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications including adding examples from the Openstax text.

Figure 6.6. “Figure 9.1 Variations in Sources of Social Influence” by Dr. Zachary Rowan and Michaela McGuire, M.A. in Intro to Criminology is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 6.3. “Pavlov Experiment” in Dunderpedia is included under fair use.

Figure 6.5. “The difference between classical and operant conditioning – Peggy Andover” by TED-Ed is shared under the Standard YouTube License.