6.3 Can Societal Reaction to Crime Cause More Crime?

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that 62 percent of people released from prison in the United States in 2012 were rearrested within 3 years, and 71 percent were rearrested within 5 years, which sheds doubt on the argument that sanctions and punishments deter criminal behavior (Durose & Antenangeli, 2021). There is also a collection of conflicting research showing either that the experience of incarceration has no effect on future criminal offending (Nagin et al., 2009) or that it increases the likelihood of someone reoffending. Still other research shows that not subjecting people to formal punishments like incarceration makes them less likely to offend later in life (Petrosino et al., 2010). Simply put, a bunch of research shows that the classical perspective offers a conflicting and incomplete explanation of criminal behavior.

What might contribute to reoffending behavior? Taking a more holistic approach in which society’s reactions to criminals are considered offers another explanation for criminal behavior and, especially, for continued criminal offending (recidivism). Important to this perspective is the sociological idea of the “looking-glass self.” According to Charles Horton Cooley and George Herbert Mead, the self is developed based on how we see ourselves, how we think others see us, and how other people actually see us.

Imagine that you go to a job interview and are confident, but when you get there, the interviewer seems uninterested and bored. You might start to think that they doubt your abilities and think you are not a good fit, even if the interviewer believes you do have the skills for the job. As you adopt your perception of what they think about you, your perception of self can change too; you might walk in feeling confident and leave feeling defeated and unqualified.

What do our thoughts of self have to do with criminal behavior? Because our sense of self is influenced by interactions with others, we know and conform to others’ expectations of us. Sociologist Erving Goffman referred to this as role performance. Such performance is one component of symbolic interactionist theory, which in part posits that people take on roles when interacting with others. Think about how you present yourself and your life on Instagram versus LinkedIn. You probably present yourself differently to your friends and family than you do to professional contacts as a way of managing your image and the way people perceive you (figure 6.9). However, the process of role-taking can also result in criminal behavior. Furthermore, the way that people react to our presentation of self can lead to us being viewed as criminal.

Learn More: Conforming to Criminality

For centuries, researchers have been trying to understand how people can commit deplorable acts and why they do so. The Nazi genocide in World War II was a motivator for a lot of this research because it was (and still is) a struggle to understand how so many people went along with what the Nazis were doing.

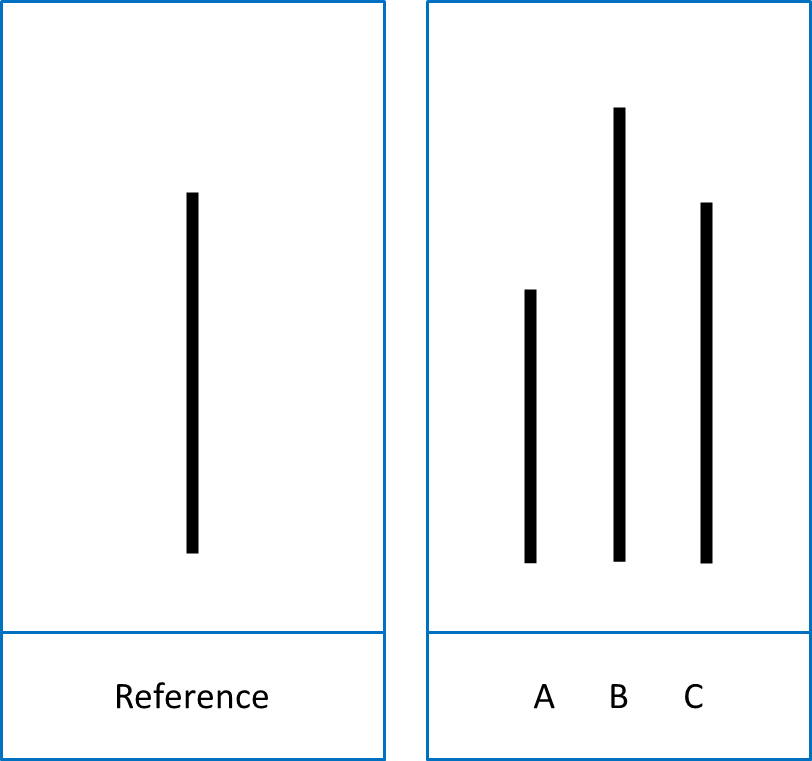

Psychologist Solomon Asch thought people were just conforming for their own protection. He conducted a study on conformity in the 1950s. His study focused on a fake “vision test” in which a group of students were asked to look at three lines and decide which line matched the length of the reference line (figure 6.10). What he was really studying was whether participants would change their answers to match (conform) with others in the group. Asch found that 75% of the participants conformed at least once, and 5% conformed every time. Asch’s study showed how conformity is overtrained in our educational system. Think back to elementary school and how conformity was rewarded. We are taught to conform, and as a result, going against a group is difficult for most.

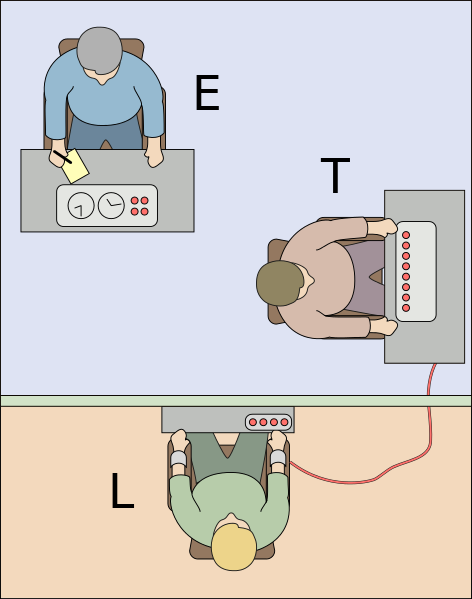

In 1961, Stanley Milgram followed up Asch’s experiment with his own that focused on obedience (figure 6.11). Milgram tried to answer the question of whether or not it was possible that many of the Nazis had simply been obediently following orders. The experiment setup was simple. There was a teacher and a learner. Unbeknownst to the “teacher,” the “learner” was a plant in the study (an actor) and knew what was going on. The teacher would read a list of words, and the learner had to recall a particular pair from a list of four possible choices. If the learner missed an answer, the teacher was supposed to give them an electric shock. Although the learner was not actually hooked up to a real machine that would produce a shock, the teacher believed that they were. When the teacher paused, not wanting to shock the learner (who had previously revealed that they had been checked out for heart issues), the facilitator of the experiment would say, “The experiment requires you to continue,” “It is absolutely essential that you continue,” and finally, “You have no other choice but to continue.” Even after the learner screamed, 65% of the participants in the teacher role continued to shock the learner up to the highest level (450 volts), and all the participants in the teacher roles continued administering shocks up to 300 volts. All the teachers shocked the learner at least once. Milgram (Mcleod, 2023) later explained in 1974, that his most important finding in this study was the “extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any length on the command of an authority.”

In 1971, Phillip Zimbardo conducted the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment in which college student participants were randomly assigned the roles of either “guard” or “prisoner.” In this study, the guards quickly began using their power to brutalize and humiliate the prisoners. The experiment was designed to last 2 weeks, but because of the trauma experienced by the participants, it was stopped after only 6 days. In this experiment, participants were not guided by an authority figure but rather by their own belief of how they were supposed to behave in their specific roles. If you want to learn more about this controversial study, you can watch the 8-minute video in figure 6.12.

These studies exemplify the significance of social interaction and reaction, role performance and identity management, and our tendencies to conform our behavior based on social expectations or pressure.

Labeling Theory

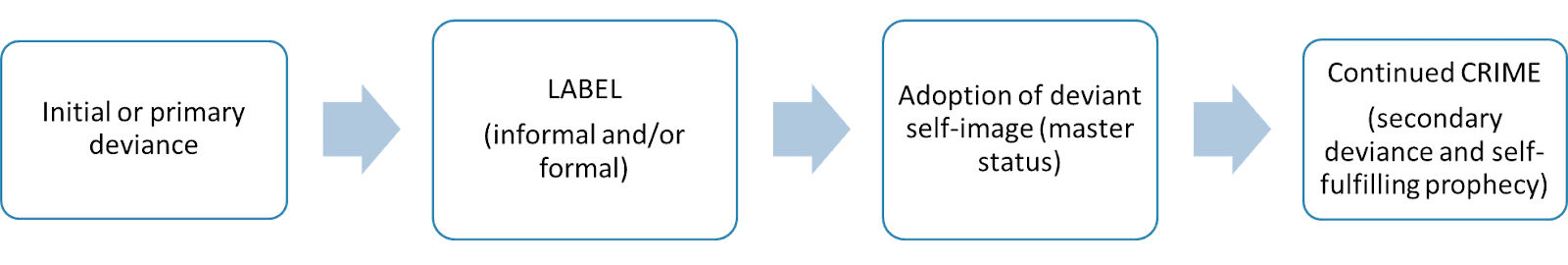

Rooted in the ideas of self-presentation and symbolic interactionism, American sociologist Howard Becker (1963) believed that “deviance is not a quality of the act the person commits, but rather a consequence of the application by others of rules and sanctions to an offender.” In other words, according to Becker’s labeling theory, someone only becomes deviant or criminal once that label is applied to them (figure 6.13). This can occur through negative societal reactions that ultimately result in a tarnished and damaged self-image and negative social expectations.

In an earlier formulation of labeling theory, Frank Tannenbaum (1938) referred to the process wherein a stigmatizing label may lead a person to start seeing themselves as a criminal. This occurs through “a process of tagging, defining, identifying, segregating, describing, emphasizing, making conscious and self-conscious” the criminal traits in question (Tannenbaum, 1938, p. 19-20). He calls this process the dramatization of evil. In this drama, the specialized treatment a young person is given by the police and courts is instrumental in leading them to see themselves as a criminal.

Sociologist Edwin Lemert expanded on the concepts of labeling theory and identified two types of deviance that affect identity formation. Primary deviance is a violation of norms that does not result in any long-term effects on the individual’s self-image or interactions with others. Speeding is a deviant act, but receiving a speeding ticket generally does not make others view you as a bad person, nor does it alter your own self-concept. Individuals who engage in primary deviance still maintain a feeling of belonging in society and are likely to continue to conform to norms in the future.

Sometimes, in more extreme cases, primary deviance can morph into secondary deviance. Secondary deviance occurs when a person’s self-concept and behavior begin to change after their actions are labeled as deviant by members of society. The person may begin to take on and fulfill the role of a “deviant” as an act of rebellion against the society that has labeled them as such. For example, consider a high school student who often cuts class and gets into fights. The student is reprimanded frequently by teachers and school staff, and soon enough, they develop a reputation as a troublemaker. As a result, the student starts acting out even more and breaking more rules. The student has adopted the “troublemaker” label and embraced this deviant identity. Secondary deviance can be so strong that it bestows a master status on an individual. A master status is a label that describes the chief characteristic of an individual. In other words, a person can be resocialized into a deviant role and their identity based on social reaction to and labeling of an initial deviant act. Some people see themselves primarily as doctors, artists, or grandparents, while others see themselves as people who beg, commit crimes, or use drugs.

To illustrate how important the label is in continued criminal behavior, consider this example. A high school student steals an SAT-prep book, doesn’t get caught, uses it to get a great score on the SATs, gets into and graduates from a good college, goes to law school, and later becomes a successful judge. The initial deviance or primary deviation did not really affect the student or their future. On the other hand, let’s assume the student was caught stealing the book, and the store owner pressed charges. When everyone at school finds out, parents and teachers might make comments about the student’s lack of integrity or character. The resulting criminal record (formal label) and reputation (informal label) could impact the student’s scholarship opportunities, make college dreams less accessible, and cause anxiety about the now uncertain future. As a result of not attending college, the student starts to feel inferior to classmates who did and begins selling drugs on the side to make more money, leading to an arrest for distributing illicit substances.

In this example, we can see how the social reaction to the student’s primary deviance and the resulting formal and informal labels impacted the student’s future offending behavior. Such a process can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies in which a person acts in line with the label that has been placed on them because they start to conform to others’ expectations of them. Many teen and young adult comedies (figure 6.14 A and B) explore related ideas of role performance, presentation of self, and labeling theory in action.

Labeling theory may help us better understand the high rate of recidivism in the United States that was discussed previously. One of the most difficult labels in society for people to see past is the label of the “criminal.” Labeling theory suggests that once an individual is labeled, they may begin to identify with that label, and continue to engage in behaviors consistent with those labels. In other words, criminal sanctions may backfire because labeling someone as a “delinquent” or “criminal” may actually increase their future delinquency and criminal behavior. (figure 6.15)

Activity: Rosenhan on Being Sane in Insane Places

- What emotions, images, or characteristics come to mind when you hear the terms “insane” or “sane”?

- How does this study relate to labeling theory?

- Think about the time and context in which Rosenhan’s study took place. How can culture and time impact what is considered deviant behavior?

- What are some terms used to describe people who commit crime or become involved in the criminal justice system that might become stigmatizing labels?

- How might Rosenhan’s study relate to the experience of being incarcerated in prison?

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Can Societal Reaction to Crime Cause More Crime?

Open Content, Original

“Can Societal Reaction to Crime Cause More Crime?” by Jessica René Peterson and Mauri Matsuda is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Learn More: Conforming to Criminality” by Curt Sobolewski and Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Jessica René Peterson.

“Activity: Rosenhan on Being Sane in Insane Places” by Jessica René Peterson and Mauri Matsuda is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.10. “Asch study example lines” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.15. “Labeling Theory Diagram” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Can Societal Reaction to Crime Cause More Crime? Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Labeling Theory” is adapted from:

- “Labeling Theory,” Introduction to Criminology by Dr. Sean Ashley is licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson and Curt Sobolewski, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include adding extensive examples, providing summary transitions, and tailoring to the American context.

- “Labeling Theory,” Psychology 2e, Openstax, by Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson and Curt Sobolewski, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include adding extensive examples and providing summary transitions.

Figure 6.9. Graphic adapted from Instagram logo, which is in the Public Domain; LinkedIn logo, which is in the Public Domain, CC0 1.0; and Blush Design, which is licensed under the Blush Design License.

Figure 6.11. “Milgram experiment v2” by Fred the Oyster is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved

Figure 6.12. “Stanford Prison Experiment” by Jo Taylor-Campbell is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 6.13. “Labeling theory” by Sociology Live! is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 6.14. Images from Easy A and Mean Girls are included under fair use.

Figure 6.16. “Rosenhan – Being Sane in Insane Places” by Mr Bodin is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.