9.2 Continuing and Emerging Crime and Victimization Topics

Although there may not be a consensus on the cause(s) of crime, one thing is certain: crime is not going away. Understanding root causes, risk factors, and more can help us mitigate risk, prevent or treat crime, and make our communities safer. All of what we discussed in Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 is still true! Going forward, the field of criminology will and should continue to study everything from property crime to violent crime. Here, we will discuss a few topics that are either newly emerging, highly impactful, or particularly intriguing to the public or researchers:

- mass murder

- crime and media

- gender-based violence

- cybercrime

Mass Murder

While other countries definitely experience their own types of tragedies, the United States has become known for certain types of horror-filled events where one or a few individuals take the lives of many. A mass killing or mass murder is federally defined as a single incident in which three or more people are killed in a public place (Investigative Assistance, 2013). The types of mass murder vary by the weapon used (such as a firearms, knives, explosives, vehicles, or even airplanes), by the perpetrator (such as a lone wolf, members of a cult, or religious extremists), by the amount of time between killings (meaning all in one event or across multiple locations), and by the motive (such as hate/bigotry, mental illness, religious extremism, or politics). What does not vary is that each type of mass murder includes the killing of at least three people by at least one perpetrator. With so many factors involved, there is a lot of variety in mass murders, despite them being some of the least common crimes committed.

Many contemporary mass murder single events are also termed mass shootings because of the use of firearms to kill or injure the greatest number of people in the shortest amount of time. These killings happen in the same location, such as at a school, workplace, public location, or event – and at the same time. School shootings, in which students arrive heavily armed and ready to kill their classmates and teachers, have gone from being extremely rare to becoming frighteningly common (figure 9.2). The incident most often referenced as the start of this horrible trend is the massacre at Columbine High School on April 20, 1999. Two high school seniors from the school, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, murdered 12 students and one teacher and injured another 21 people. They then killed themselves in the school library. At the time, Columbine was the deadliest school shooting in U.S. history, and even though it was not the first school shooting in the United States, it changed how we viewed safety in schools. Schools now routinely practice lockdowns and have active shooter drills. Students and teachers alike are all very aware of the possibility of a school shooting on their campus.

Understanding the reasons, motives, and causes of different types of mass murder events may be key to reducing them. The debate over gun control and accessibility in this country is a controversial policy discussion that comes up in every election and, typically, after every mass shooting on the news. Criminologists are well-situated to meaningfully contribute to this conversation.

Learn More: Mass Shootings in America

As we will discuss in this chapter, a mass shooting is defined as an event in which three or more people are shot (not counting the shooter). The Gun Violence Archive, an independent data collection and research group, keeps daily track of all gun violence in the United States dating back to 2014. Specific to mass shootings, 2023 was one of the top three deadliest years since the organization began tracking this data. In 2023, there were 656 mass shootings in this country. In 2022, there were a total of 646 mass shootings, in 2021, there were 689, and 2020 had a total of 610. These numbers show a frightening trend, with each year having almost double the number of mass shootings as occurred each year between 2014 and 2019, when the average was 348 mass shootings per year (Gun Violence Archive, 2024).

The largest mass shooting in terms of number of deaths and injuries in U.S. history occurred in Las Vegas, Nevada, on October 1, 2017. Twenty-two thousand fans were in attendance at the Route 91 Harvest Music Festival on the Las Vegas Strip when 64-year-old Stephen Paddock opened fire on the crowd. Paddock fired over 1,000 shots from inside his hotel room, a corner suite on the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino. Over the course of one week leading up to the shooting, he had moved an arsenal of firearms in 22 suitcases into two suites. These weapons included 14 AR-15 rifles, eight AR-10 rifles, one bolt-action rifle, and one revolver. Some of the AR-15 rifles were also equipped with bump stocks that allowed them to fire in rapid succession, and 12 of them had 100-round magazines. On September 30th, he placed a “do not disturb” sign on the doors of both of the suites. For 10 minutes, Paddock fired indiscriminately into the crowd at the concert as they tried to escape to safety. When police breached the door of the hotel suite after the shooting, Paddock was found dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to his head. His motive for the mass shooting remains unknown.

Shootings like this, although on a smaller scale, have become part of American culture. No other country in the world experiences mass shootings with the type of frequency that we do here in the United States. This phenomenon is not only not getting better, it appears to be getting far worse and gaining momentum.

Supplemental Resources

- You have the option to learn more about the Gun Violence Archive [Website].

- If you want to keep up with the Supreme Court’s cases and opinions, including those about ghost guns [Website] or gun rights/control [Website], you can follow Scotusblog [Website].

Crime and Media

Crime and media are intricately and historically linked. In our modern society, crime infotainment such as documentaries, podcasts, tv series, and other true crime media are incredibly popular. Journalistic reporting of crime and victimization has changed drastically since the time of print newspapers as we now get stories about crime from social media and other online outlets. Additionally, there is growing distrust for “the media” and “the news”—the ambiguous collective—that leads to public questioning of crime-related information.

Criminologists and media scholars alike have their work cut out for them. There is a heap of research already that assesses how the media portrays victims, perpetrators, and crime issues. Much of this research looks at the ways in which gender, race, religion, and other identities are represented in crime-related media. For many criminologists, the accuracy of and impact that these portrayals have on victims, public opinion about justice issues, knowledge of the legal system, and more are incredibly important.

Activity: Serial Murder in the Media

Serial murder differs from mass murder in at least two important ways. First, in serial murder, multiple people are murdered as part of more than one incident. Second, serial murder includes cooling off periods that separate each murder. In other words, the person committing the murders has time for any adrenaline-fueled emotional highs to subside before they commit the next murder. Scholars who study serial murder and serial murderers look at things like who is targeted and their characteristics (e.g., gender, race), as well as the lifestyle, education, occupation, and motivations of the people committing the murders. Although this type of crime is relatively rare, the public is fascinated by these cases.

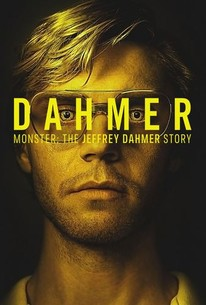

In 2022, the show Dahmer—Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story came out on Netflix (figure 9.3). With Evan Peters in the lead role, the show quickly became very popular, sparking memes and discussion across the internet. Although it was not a novel idea and many shows, documentaries, films, and podcasts explore the lives and crimes of famous serial killers, this one brought our morbid curiosity and the ethics related to these stories to the forefront.

Read this article about Rita Isbell [Website], the sister of Errol Lindsey who was one of Jeffrey Dahmer’s victims, to get one perspective related to this topic. Then answer the following questions.

- Does the telling of serial murder cases in the media educate or exploit? Think about the pros and cons, advantages and disadvantages of serial murder stories in different forms of media.

- Does having the details of these cases help educate the public on the realities of serial murder? Does that education help us be more prepared, able to avoid, or able to help victims of serial murder?

- Or do these stories exploit tragedies for profit? Do they further harm victims? Do they glorify murder and murderers?

- Does your answer differ when you consider different forms of media? For example, TV news media, internet news media, documentaries, “based on a true story” fictional films, TV shows, or podcasts. Explain your thoughts.

Supplemental Resources

- If you want to see public opinion and listenership of true crime podcasts, check out the Pew Research Center’s Survey [Website].

- If you want to see a famous example of how media coverage of crime can impact the involved parties watch the documentary Amanda Knox [Streaming Video] on Netflix.

Gender-Based Violence

Gender-based violence, a broad category of violence that is directed at someone because of their gender, is a phenomenon that occurs in all parts of the world and across time. Often, gender-based violence refers to violence against women that includes sexual assault and rape, intimate partner violence (violence committed by a sexual/romantic partner or ex-partner), domestic violence (violence in a domestic/family setting), and femicide (the killing of women because of their gender). According to The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, 47% of women in the United States reported any contact sexual violence – including rape, sexual coercion, and unwanted sexual contact – physical violence, and/or stalking victimization by an intimate partner at some point in their lifetime (Leemis et al., 2022). Additionally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that between 2003 and 2014, 55% of the homicides of American women involved an intimate partner, and non-Hispanic Black women had the highest rate of dying by homicide (Petrosky et al., 2017). Many cultural factors have been tied to these forms of gender-based violence, such as patriarchal structures and rape culture (Johnson & Johnson, 2021).

Gender-based violence can also include infanticide, which is the killing of an infant; honor killing, which is the killing of someone who has allegedly dishonored their family; female genital mutilation, which is the partial or total removal of female external genitalia; forced marriage; and human trafficking. Worldwide, girls and women are subjected to these types of violence at a disproportionate rate (UN Women, 2020).

Another area of focus regarding gender-based violence relates to hate crime victimization, particularly of transgender individuals. In a study that looked at violent victimization between 2017 and 2020, the rate of violent victimization against transgender persons was 2.5 times the rate among cisgender persons (Truman & Morgan, 2022). Relatedly, “corrective rape,” or rape that is intended to force the victim to conform to a heterosexual or cisgender identity, is a form of sexual violence often perpetrated against women and members of the LGBTQIA+ community. The issue of gender-based violence, in all of its forms, is not unique to the United States and is in need of continued criminological study.

Learn More: Gender-Based Hate Crimes

Hate crimes are defined by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) as criminal acts that are at least partly motivated by the perceived identity or group affiliation of the victim (figure 9.4). In other words, hate itself, and often hate speech, is not considered a hate crime. There are several federally protected identities, but states can decide which other groups will be protected under hate crime legislation within their borders. Gender and gender identity are not protected in every state.

As discussed in Chapter 2, the FBI collects data on hate crimes. There are few hate crimes against women and transgender people reported each year. However, this data source is severely limited and does not represent the actual amount of hate crime victimization taking place. Hate crimes are shakily defined, significantly underreported, often misclassified by law enforcement, and difficult to prove and prosecute. First, legislation typically does not recognize various forms of gender-based violence as a hate crime. For example, rape targeting women victims will not show up in the hate crime data, even though the victim was likely chosen because of gender.

Second, hate crimes are underreported for multiple reasons. According to the National Crime Victimization Survey, people choose not to report for various reasons, such as fearing retaliation or fearing or distrusting the police. For transgender individuals, reporting their victimization might also mean outing themselves and placing themselves in danger. A study in West Virginia in 2011 found that hate crimes were undercounted by approximately 67%, and, related to the third limitation, they found classification errors in the way police were reporting hate crimes (Haas et al., 2011).

Finally, hate crimes can be difficult to prove and prosecute in court. Without clear evidence, such as video or witness accounts of a perpetrator using slurs during the commission of a crime, it may not be possible to secure a conviction. Prosecutors may fear that a hate crime charge could jeopardize the entire case and thus choose not to pursue such charges. Hate crime charges also tend to spark public and political debates, which may deter a prosecutor from pursuing hate crime charges.

The intersection of gender-based violence and victimization with hate crimes is not clear and will likely continue to evolve.

Supplemental Resources

- Learn more about the intersection of transphobia and hate crimes by reading this Insider investigation that uncovered 15 murders driven by transphobia (only one of which was successfully prosecuted as a hate crime): “‘Love us in private and kill us in public’: How transphobia turns young men into killers” [Website].

- Learn more about intimate partner violence at the National Domestic Violence Hotline [Website], which includes statistics, research, and resources.

- Learn more about sexual assault at the National Sexual Assault Hotline [Website], which includes statistics, research, and resources.

Cybercrime

Technological advancements have drastically changed the way we live our lives. New tools and technologies can make life easier, but they can also create new opportunities for harm and victimization. Not only is it challenging for the law to keep up with these changes, but the field of criminology has to adapt and evolve as well.

Cybercrime is an umbrella term that refers to essentially all crime that is committed via the internet or with the use of computers. As Artificial Intelligence (AI) capabilities improve and become harder to detect, issues such as deepfake videos that impose someone’s likeness onto an existing video may change the way fraud, identity theft, blackmail, and more are committed (figure 9.5). Although internet and mobile phone connectivity varies across the globe and is especially lacking in developing countries, 95% of the world’s population has mobile broadband network coverage and 63% are using the internet (International Telecommunications Union, 2022). The expansion of these network connections makes it easier for organized crime groups to facilitate the trafficking of drugs, people, guns, and other contraband.

Criminologists will continue to research how to detect these threats, the impact of cybercrime victimization, and practical investigative practices for identifying and catching people engaged in cybercrime. This topic is forever and fast-changing as our technologies grow and change.

Activity: Deepfake Pornography

Read this brief article, “Taylor Swift and the Dangers of Deepfake Pornography” [Website], as well as Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s press release [Website] about federal legislation that was introduced in March 2024.

- How do you think deepfake pornography impacts the privacy and rights of individuals whose faces are used without consent?

- Should there be specific laws addressing the creation and dissemination of deepfakes? Why or why not?

- How might exposure to deepfake pornography affect individuals, both those depicted and viewers?

- What responsibilities do social media platforms, tech companies, or pornography websites have in preventing the spread of deepfake pornography?

- How does deepfake pornography intersect with issues of gender, power, and exploitation?

Supplemental Resources

- If you are interested in learning more about cybercrime and career opportunities for investigating cybercrime, check out the FBI’s cyber threat web page [Website].

- You can learn how to report cybercrime via the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) [Website].

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Continuing and Emerging Crime and Victimization Topics

Open Content, Original

“Continuing and Emerging Crime and Victimization Topics” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Mass Murder” by Jessica René Peterson and Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Learn More: Mass Shootings in America” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Jessica René Peterson.

“Continuing and Emerging Crime and Victimization Topics Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 9.2. “Mass Shootings in the U.S.” by JoleBruh is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.4. Image by Dan Edge is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 9.5. Image by harshahars from Pixabay is licensed under the Pixabay License.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 9.3. DAHMER is included under fair use.