2 Behaviorism

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify key elements of behaviorism

- Explain strategies utilized to implement behaviorism

- Summarize the criticisms of behaviorism and educational implications

- Explain how equity is impacted by behaviorism

- Identify classroom strategies to support the use of behaviorism

- Select strategies to support student success utilizing behaviorism

- Develop a plan to implement the use of behaviorism

Image 1.1

SCENARIO:

Mr. Mack was a brand new fifth grade teacher, full of hope, creative ideas and good intentions. However, he was stumped as to how to get his student Johnny to stay in his seat. Sometimes, Johnny would throw chairs out of frustration, and other times Mr. M could not even get a word out of him. Mr. M tried to get Johnny to look him in the eye as he was giving instructions, thinking that this would help Johnny to focus on the task at hand; this proved to be very challenging. Sometimes Mr M could just tell that Johnny was about to bolt outside and so he would warn Johnny to stay in his seat, letting him know that if he left his chair he would have to miss recess. Unfortunately, Johnny often had to miss recess and stay inside by himself. Mr. M felt exhausted and defensive when he had to consult with the school counselor. The counselor offered to come and observe the classroom and discuss possible strategies for helping Johnny and Mr. M.

As you read this chapter on behaviorism, consider how behaviorist strategies could help both Mr. M and Johnny to have a more productive relationship, and a better teaching and learning experience.

Video 1.1

Introduction

Behaviorism is primarily concerned with observable and measurable aspects of human behavior. In defining behavior, behaviorist learning theories emphasize changes in behavior that result from stimulus-response associations made by the learner.

Behaviorism:

|

Image 1.2

John B. Watson (1878-1958) and B. F. Skinner (1904-1990) are the two principal originators of behaviorist approaches to learning. Watson believed that human behavior resulted from specific stimuli that elicited certain responses. Watson’s basic premise was that conclusions about human development should be based on observation of overt behavior rather than speculation about subconscious motives or latent cognitive processes (Shaffer, 2000).

Watson’s view of learning was based in part on the studies of Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936). Pavlov was well known for his research on a learning process called classical conditioning. Classical conditioning refers to learning that occurs when a neutral stimulus becomes associated with a stimulus that naturally produces a behavior. Skinner believed that that seemingly spontaneous action is regulated through rewards and punishment. Skinner believed that people don’t shape the world, but instead, the world shapes them. Skinner also believed that human behavior is predictable, just like a chemical reaction.

Image 1.3

What is Behaviorism?

Behaviorism is primarily concerned with observable and measurable aspects of human behavior. In defining behavior, behaviorist learning theories emphasize changes in behavior that result from stimulus-response associations made by the learner. Behavior is directed by stimuli. An individual selects one response instead of another because of prior conditioning and psychological drives existing at the moment of the action (Parkay & Hass, 2000).

An individual’s response to a situation is based on prior conditioning and learned habits.

Behaviorists assert that the only behaviors worthy of study are those that can be directly observed; thus, it is actions, rather than thoughts or emotions, which are the legitimate object of study. Behaviorist theory does not explain atypical behavior in terms of the brain or its inner workings. Rather, it posits that all behavior is learned habits, and attempts to account for how these habits are formed.

Behaviorists focus on observable actions, rather than thoughts or emotions.

In assuming that human behavior is learned, behaviorists also hold that all behaviors can also be unlearned, and replaced by new behaviors; that is, when a behavior becomes unacceptable, it can be replaced by an acceptable one. A key element to this theory of learning is the rewarded response. The desired response must be rewarded in order for learning to take place (Parkay & Hass, 2000). Lessons learned from Behaviorism have guided educators over the years in thinking about strategies to change behavior.

Rewards are key to changing unacceptable behavior to acceptable behavior.

Behaviorism Advocates in Education

In education, advocates of behaviorism have effectively adopted this system of rewards and punishments in their classrooms by rewarding desired behaviors and punishing inappropriate ones. Rewards vary, but must be important to the learner in some way.

EXAMPLE FROM THE CLASSROOM:

If a teacher wishes to teach the behavior of remaining seated during the class period, the successful student’s reward might be checking the teacher’s mailbox, running an errand, or being allowed to go to the library to do homework at the end of the class period. As with all teaching methods, success depends on each student’s stimulus and response, and on associations made by each learner.

Consider: how might have Mr. Mack in the intro scenario used these types of rewards to motivate Johnny?

Image 1.4

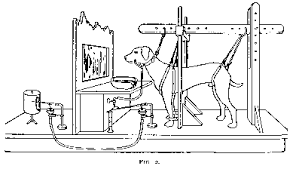

Watson’s view of learning was based in part on the studies of Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936). Pavlov was studying the digestive process and the interaction of salivation and stomach function when he realized that reflexes in the autonomic nervous system closely linked these phenomena. To determine whether external stimuli had an affect on this process, Pavlov rang a bell when he gave food to the experimental dogs. He noticed that the dogs salivated shortly before they were given food. He discovered that when the bell was rung at repeated feedings, the sound of the bell alone (a conditioned stimulus) would cause the dogs to salivate (a conditioned response). Pavlov also found that the conditioned reflex was repressed if the stimulus proved “wrong” too frequently; if the bell rang and no food appeared, the dog eventually ceased to salivate at the sound of the bell (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Classical Conditioning (Ivan Pavlov: 1849-1936)

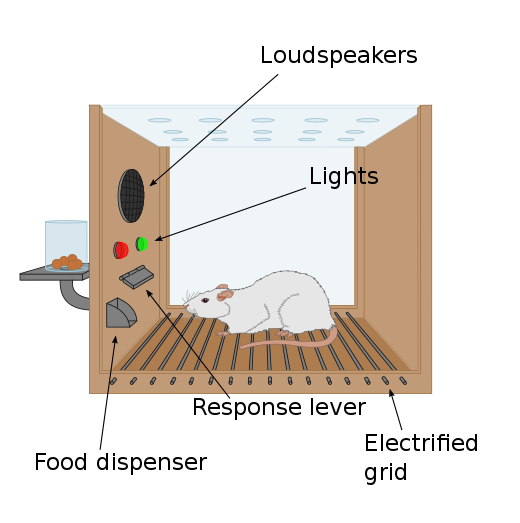

Image 1.5

Expanding on Watson’s basic stimulus-response model, Skinner developed a more comprehensive view of conditioning, known as

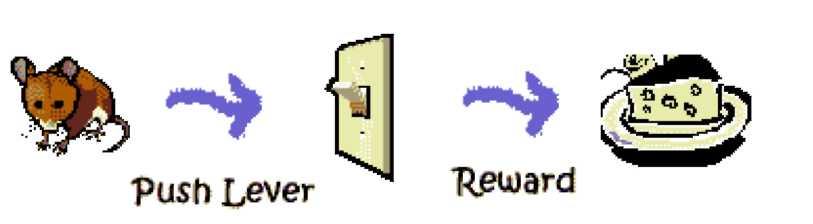

operant conditioning. His model was based on the premise that satisfying responses are conditioned, while unsatisfying ones are not. Operant conditioning is the rewarding of part of a desired behavior or a random act that approaches it (Figure 1.2). Skinner remarked that “the things we call pleasant have an energizing or strengthening effect on our behavior” (Skinner, 1972, p. 74). Through Skinner’s research on animals, he concluded that both animals and humans would repeat acts that led to favorable outcomes, and suppress those that produced unfavorable results (Shaffer, 2000). If a rat presses a bar and receives a food pellet, he will be likely to press it again. Skinner defined the bar-pressing response as operant and the food pellet as a reinforcer. Punishers, on the other hand, are consequences that suppress a response and decrease the likelihood that it will occur in the future. If the rat had been shocked every time it pressed the bar, that behavior would cease. Skinner believed the habits that each of us develops result from our unique operant learning experiences (Shaffer, 2000).

Figure 1.2. Operant Conditioning (B. F. Skinner: 1904-1990)

This illustration illustrates Operant Conditioning. The mouse pushes the lever and receives a food reward. Therefore, he will push the lever repeatedly in order to get the treat.

Behaviorist techniques have long been employed in education to promote behavior that is desirable and discourage that which is not. Among the methods derived from behaviorist theory for practical classroom application are contracts, consequences, reinforcement, extinction, and behavior modification.

Table 14: Operant conditioning as learning and as motivation

|

Concept |

Definition phrased in terms of learning |

Definition phrased in terms of motivation |

Classroom example |

|

Operant |

Behavior that becomes more likely because of reinforcement |

Behavior that suggests an increase in motivation |

Student listens to teacher’s comments during lecture or discussion |

|

Reinforcement |

Stimulus that increases likelihood of a behavior |

Stimulus that motivates |

Teacher praises student for listening |

|

Positive reinforcement |

Stimulus that increases likelihood of a behavior by being introduced or added to a situation |

Stimulus that motivates by its |

Teacher makes encouraging remarks about student’s homework |

|

Negative reinforcement |

Stimulus that increases the likelihood of a behavior by being removed or taken away from a situation |

Stimulus that motivates by its |

Teacher stops nagging student about late homework |

|

Punishment |

Stimulus that decreases the likelihood of a behavior by being introduced or added to a situation |

Stimulus that decreases |

Teacher deducts points for late homework |

|

Extinction |

Removal of reinforcement for a behavior |

Removal of motivating stimulus that leads to decrease in motivation |

Teacher stops commenting altogether about student’s homework |

|

Shaping successive approximations |

Reinforcements for behaviors that gradually resemble (approximate) a final goal behavior |

Stimuli that gradually shift motivation toward a final goal motivation |

Teacher praises student for returning homework a bit closer to the deadline; gradually she praises for actually being on time |

|

Continuous reinforcement |

Reinforcement that occurs each time that an operant behavior occurs |

Motivator that occurs |

Teacher praises highly active student for |

|

Intermittent reinforcement |

Reinforcement that sometimes occurs following an operant behavior, but not on every occasion |

Motivator that occurs |

Teacher praises highly active student sometimes |

Operant Conditioning Summary

Contracts, Consequences, Reinforcement, and Extinction

Simple contracts can be effective in helping children focus on behavior change. The relevant behavior should be identified, and the child and teacher should decide the terms of the contract. Behavioral contracts can be used in school as well as at home. It is helpful if teachers and parents work together with the student to ensure that the contract is being fulfilled.

EXAMPLE:

Victor is falling behind in class. Mrs. O notices that he hasn’t done any homework lately. Regular practice with these math skills is important preparation for the upcoming quizzes. Victor is an immigrant and is not used to having homework count. Mrs. O decides to do a homework contract with Victor. Her bilingual aid contacts the parents so they are in the loop. Mrs. O offers rewards for the number of homework that are turned in. As a reward, Victor gets to choose his new job in class and he picks feeding the pet snake “Jake.”

ANOTHER EXAMPLE:

Madison is struggling to follow classroom behavioral expectations. Ms. B and Madison meet to talk about this and agree on a behavioral contract to minimize distractions. Provisions include that the student will sit in front of the teacher, will raise hand with questions/comments, and will not leave her seat without permission. Madison will get a check mark after each lesson for doing each of these things. At the end of the week, if Madison has 90% of the check marks, she can choose a prize from the class treasure chest.

Consequences occur immediately after a behavior (Figure 1.3 below). Consequences may be positive or negative, expected or unexpected, immediate or long-term, extrinsic or intrinsic, material or symbolic (a failing grade), emotional/interpersonal or even unconscious. Consequences occur after the “target” behavior occurs, when either positive or negative reinforcement may be given.

Positive reinforcement is presentation of a stimulus that increases the probability of a response. This type of reinforcement occurs frequently in the classroom. Teachers may provide positive reinforcement by:

• Smiling at students after a correct response;

• Commending students for their work;

• Selecting them for a special project; and

• Praising students’ ability to parents.

Negative reinforcement increases the probability of a response that removes or prevents an adverse condition. Many classroom teachers mistakenly believe that negative reinforcement is punishment administered to suppress behavior; however, negative reinforcement increases the likelihood of a behavior, as does positive reinforcement. Negative implies removing a consequence that a student finds unpleasant. Negative reinforcement might include:

• Obtaining a score of 80% or higher makes the final exam optional;

• Submitting all assignments on time results in the lowest grade being dropped; and

Punishment involves presenting a strong stimulus that decreases the frequency of a particular response. Punishment is effective in quickly eliminating undesirable behaviors. Examples of punishment include:

• Students who fight are immediately referred to the principal;

• Late assignments are given a grade of “0;”

• Three tardies results in a call to the parents; and

• Failure to do homework results in after-school detention (privilege of going home is removed).

Figure 1.3 Reinforcement and Punishment Comparison

|

|

REINFORCEMENT |

REINFORCEMENT |

|

POSITIVE |

Positive Reinforcement Something is added to increase desired behavior. Ex: Smile and compliment student on good performance. |

Positive Punishment Something is added to decrease undesired behavior. Ex: Give student detention for failing to follow the class rules. |

|

NEGATIVE |

Negative Reinforcement Something is removed to increase desired behavior. Ex: Give a free homework pass for turning in all assignments. |

Negative Punishment Something is removed to decrease undesired behavior. Ex: Make student miss their time in recess for not following the class rules. |

Extinction decreases the probability of a response by withdrawal of a previously reinforced stimulus.

EXAMPLES OF EXTINCTION:

•Jane has developed the habit of saying the punctuation marks when reading aloud. Classmates reinforce the behavior by laughing when she does so. The teacher tells the students not to laugh, thus extinguishing the behavior.

• Mr. D gives partial credit for late assignments; other teachers think this is unfair, so Mr. D decides to then give zeros for the late work.

• Students are frequently late for Ms. Y’s art class, and she does not require a late pass, contrary to school policy. Ms. Y changes her policy, the rule is subsequently enforced, and the students arrive on time.

Modeling, Shaping, and Cueing

Modeling is also known as observational learning. Albert Bandura, an influential social-cognitive psychologist, has suggested that modeling is the basis for a variety of child behavior. Children acquire many favorable and unfavorable responses by observing those around them. A child who kicks another child after seeing this on the playground, or a student who is always late for class because his friends are late is displaying the results of observational learning.

“Of the many cues that influence behavior, at any point in time, none is more common than the actions of others.” (Bandura, 1986, p. 45)

Figure 1.4

In this picture, the child is modeling the behavior of the adult. Children watch and imitate the adults around them; the result may be favorable or unfavorable behavior!

Shaping is the process of gradually changing the quality of a response. The desired behavior is broken down into discrete positive movements, each of which is reinforced as it progresses towards the overall behavioral goal.

EXAMPLE OF SHAPING:

Mr. B would like his class to sit down quietly after entering the classroom, but they continue to talk after the bell rings. Mr. B gives the class one point for improvement, in that all students are seated. Subsequently, the students must be seated and quiet to earn points, which may be accumulated and redeemed for rewards.

Cueing is providing a student with a verbal or non-verbal cue as to the appropriateness of a behavior.

EXAMPLE OF CUEING:

Mrs. R is working with Danny, who often answers aloud instead of raising his hand. At the end of asking a question, Mrs. R says to the class, “I’ll call on someone who is raising their hand,” to help Danny remember to perform an action (hand raising) at a specific time (when a question is asked).

Behavior Modification

Behavior modification is a method of eliciting better classroom performance from reluctant students. It has six basic components:

1. Specification of the desired outcome. In other words, what must be changed and how it will be evaluated? One example of a desired outcome is increased student participation in class discussions.

2. Development of a positive, nurturing environment (by removing negative stimuli from the learning environment). In the above example, this would involve a student-teacher conference with a review of the relevant material, and calling on the student when it is evident that she knows the answer to the question posed.

3. Identification and use of appropriate reinforcers (intrinsic and extrinsic rewards). A student receives an intrinsic reinforcer by correctly answering in the presence of peers, thus increasing self-esteem and confidence.

4. Reinforcement of behavior patterns develop until the student has established a pattern of success in engaging in class discussions.

5. Reduction in the frequency of rewards-a gradual decrease the amount of one-on-one review with the student before class discussion.

6. Evaluation and assessment of the effectiveness of the approach based on teacher expectations and student results. Compare the frequency of student responses in class discussions to the amount of support provided, and determine whether the student is independently engaging in class discussions. (Brewer, Campbell, & Petty, 2000)

Further suggestions for modifying behavior can be found at the mentalhealth.net web site. These include changing the environment, using models for learning new behavior, recording behavior, substituting new behavior to break bad habits, developing positive expectations, and increasing intrinsic satisfaction.

Criticisms of Behaviorism

As you read the criticisms and limitations of behaviorism, consider how the pure use of behaviorism would impact Johnny, the student in Mr. M’s class.

Behaviorism can be viewed as overly simplistic and not addressing the unique needs of individuals. These unique needs may not consider multiple aspects of humans such as, experiences and an individual’s free will. In addition, humans all learn in different ways and may not consistently respond to stimulus. This leads individuals to believe that various external factors may impact behavior. “Important factors like emotions, expectations, higher-level motivation are not considered or explained” (McLeod, 2017).

Individuals are unique and may not all respond the same to stimulus. Additional factors (see left) may need to be considered.

Additional factors may include (not a full list):

- Learning differences

- Socioeconomic status

- Gender identity

- Cultural background

- Disabilities

- Psychological or social emotional

Image 1.6

Reflection Questions:What other factors do you think impact an individual’s behavior?How would you integrate these behaviors with the use of behaviorism? |

Educational Implications

Using behaviorist theory in the classroom can be rewarding for both students and teachers. Behavioral change occurs for a reason; students work for things that bring them positive feelings, and for approval from people they admire.

Individuals make changes in behavior for many different reasons.

They change behaviors to satisfy the desires they have learned to value. They generally avoid behaviors they associate with unpleasantness and develop habitual behaviors from those that are repeated often (Parkay & Hass, 2000). The entire rationale of behavior modification is that most behavior is learned. If behaviors can be learned, then they can also be unlearned or relearned. Behavior is learned and can be modified.

A behavior that goes unrewarded will be extinguished. Consistently ignoring an undesirable behavior will go far toward eliminating it. When the teacher does not respond angrily, the problem is forced back to its source-the student. Other successful classroom strategies are contracts, consequences, punishment and others that have been described in detail earlier. Behaviorist learning theory is not only important in achieving desired behavior in mainstream education. Special education teachers have classroom behavior modification plans to implement for their students. These plans assure success for these students in and out of school.

Image 1.7

Reflection Question:Explain some effective ways to change behaviors. What else should you consider when attempting to modify behavior? |

Chapter Discussion Questions:

- What are the key elements of behaviorism?

- Can you explain the benefits and drawbacks of behaviorism?

- How would you summarize the ways to implement behaviorism?

- What approach would you use to support our student (Johnny in Mr. M’s class)?

- What is the relationship between equity and behaviorism?

- What information would you use to support or not support the use of behaviorism in a diverse classroom

For additional information on behaviorism:

https://kstatelibraries.pressbooks.pub/seifertsutton/chapter/the-learning-process/

ATTRIBUTIONS

Image 1.1 “Kids Jumping off Dune “by Great Sand Dunes National Park and Reserve is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image 1.2 “B. F. Skinner” by Andrea Joseph is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image 1. 3: “Skinner Box” by AndreasJS is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image 1.4 “Behaviorism: Key Theorists” by Jocelyn Ferguson is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image 1.5 “The setup for Ivan Pavlov research on dog’s reflex” by Yerkes, R. M., & Morgulis, S. is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image 1.6 “Intersectionality” by Top 10 website is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image 1.7 Attribution not required:https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1452325utm_content=shareClip&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=pxhere

Video 1.1 “Behaviorism: Pavlov, Watson, and Skinner” by youtube is in the Public Domain

REFERENCES

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundation of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Brewer, E. W., Campbell, A. C., & Petty, G. C. (2000). Foundations of workforce education. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

Huitt, W., & Hummel, J. (1998). The behavioral system. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/behavior/behovr.html

McLeod, S. A. (2017, February 05). Behaviorist approach. Simply Psychology. www.simplypsychology.org/behaviorism.html

Parkay, F. W., & Hass, G. (2000). Curriculum planning (7th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Shaffer, D. (2000). Social and personality development (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thompson Learning.

Skinner, B. (1972). Utopia through the control of human behavior. In John Martin Rich (Ed.), Readings in the philosophy of education. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

ADDITIONAL READING

Credible Articles on the Internet

Classroom management theories and theorists. (2013). Retrieved from

Cunia, E. (2005). Behavioral learning theory. Principles of Instruction and Learning: A Web Quest. Retrieved from

http://erincunia.com/portfolio/MSportfolio/ide621/ide621f03production/behavior.htm

Graham, G. (2002). Behaviorism. In E. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Stanford, CA: The Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2002/entries/behaviorism/

Hauser, L. (2006). Behaviorism. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from http://www.utm.edu/research/iep/b/behavior.htm

Huitt, W., & Hummel, J. (2006). An overview of the behavioral perspective. Educational Psychology Interactive.

Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/behavior/behovr.html

Huitt, W. (1996). Classroom management: A behavioral approach. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/manage/behmgt.html

Huitt, W. (1994). Principles for using behavior modification. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/behavior/behmod.html

Huitt, W., & Hummel, J. (1997). An introduction to classical (respondent) conditioning. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/behavior/classcnd.html

Wozniak, R. (1997). Behaviorism: The early years. Bryn Mawr, PA: Bryn Mawr College. Retrieved from http://www.brynmawr.edu/Acads/Psych/rwozniak/behaviorism.html

Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles

Bush, G. (2006). Learning about learning: From theories to trends. Teacher Librarian, 34(2), 14-18. Retrieved from

http://proxygsu-dal1.galileo.usg.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/224878283?accountid=1040

Delprato, D. J., & Midgley, B. D. (1992). Some fundamentals of B. F. skinner’s behaviorism. The American Psychologist,

47(11), 1507. Retrieved from http://www.galileo.usg.edu

Ledoux, S. F. (2012). Behaviorism at 100. American Scientist, 100(1), 60-65. Retrieved from http://proxygsu-dal1.galileo.usg.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1009904053?accountid=10403

Moore, J. (2011). Behaviorism. The Psychological Record, 61(3), 449-463. Retrieved from http://www.galileo.usg.edu

Ruiz, M. R. (1995). B. F. skinner’s radical behaviorism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19(2), 161. Retrieved from http://proxygsu-dal1.galileo.usg.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=slh&AN=9506232514&site=ehost -live

Ulman, J. (1998). Applying behaviorological principles in the classroom: Creating responsive learning environments.

The Teacher Education, 34(2), 144-156.

Books in Dalton State College Library

Bjork, D. W. (1997). B.F. Skinner: A life. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Skinner, B. F. (1974). About behaviorism (1st ed.). New York, NY: Random House. Retrieved from

http://books.google.com/books?id=Ndx7awW_1OcC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false

Smith, L. D., & Woodward, W. R. (1996). B.F. Skinner and behaviorism in American culture.

Bethlehem, London; Cranbury, NJ: Lehigh University Press.

Todd, J. T., & Morris, E. K. (1995). Modern perspectives on B.F. Skinner and contemporary behaviorism.

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Interactive Tutorials

Psychology Department. (2017). Positive reinforcement tutorial. Athabasca, Alberta, Canade: Athabasca University. Retrieved from https://psych.athabascau.ca/open/prtut/index.php

Video(s)

B. F. Skinner: A fresh appraisal. (1999). Retrieved from

http://digital.films.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?aid=8691&xtid=44905