11 Theory of Human Motivation

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify key elements of the theory of human motivation

- Explain strategies utilized to implement the theory of human motivation

- Summarize the criticisms of and educational implications of the theory of human motivation

- Explain how equity is impacted by the theory of human motivation

- Identify classroom strategies to support the use of the theory of human motivation

- Select strategies to support student success utilizing the theory of human motivation

- Develop a plan to implement the use of the theory of human motivation

Image 11.1

Scenario:

Third grade teacher Ms. Brodsky noticed that Anna was falling asleep in class again. She had deep dark circles under her eyes and she was having trouble focusing. Ms. Brodsky had prepared a part of her classroom especially for this moment. The corner of the room had a warm quiet alcove loaded with bean bag chairs, pillows and a low table with books. This was the place she brought kids who just needed a little extra TLC (tender loving care). She asked Anna to join her to do some reading while her instructional aide worked with the rest of the class. Ms. Brodsky pulled out some snacks and juice for Anna who ate them like it was her first meal in quite a while. She encouraged her to get comfy and read to her for a little bit. Eventually, Anna began to perk up and was eager to rejoin the activities with the rest of the class.

What is it that Ms. Brodsky understood about Anna’s needs and motivations? As you learn about Maslow’s Theory of Human Motivation, consider how all children arrive at our school doors with different circumstances. Some may have slept in a car or slept very little, or not had a meal or proper hygiene, and all of these things affect their ability to learn as Maslow’s theory points out, and as Ms. Brodsky well understood. Children can not learn if they are too tired or too hungry, and effective educators understand the need to pause and help the child wherever they happen to be.

Check out these videos as an introduction:

Video 11.1

Video 11.2

Image 11.2: Maslow

INTRODUCTION

Abraham Harold Maslow (1908-1970) was born in Brooklyn, New York. His parents were Jewish immigrants from Russia who were rather uneducated. Maslow was the sole Jewish boy in his neighborhood and was unhappy and lonesome throughout the majority of his childhood. Maslow also had problems within his home. His father continually degraded him and pushed him to excel in areas that were of no interest to him. His mother also treated him poorly. Because of this Maslow wanted no interaction with his parents. Maslow perceived his mother as being entirely insensitive and unloving. After a difficult childhood, Maslow was able to obtain a Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin in 1934. After he received his PhD, he continued to teach at the University of Wisconsin.

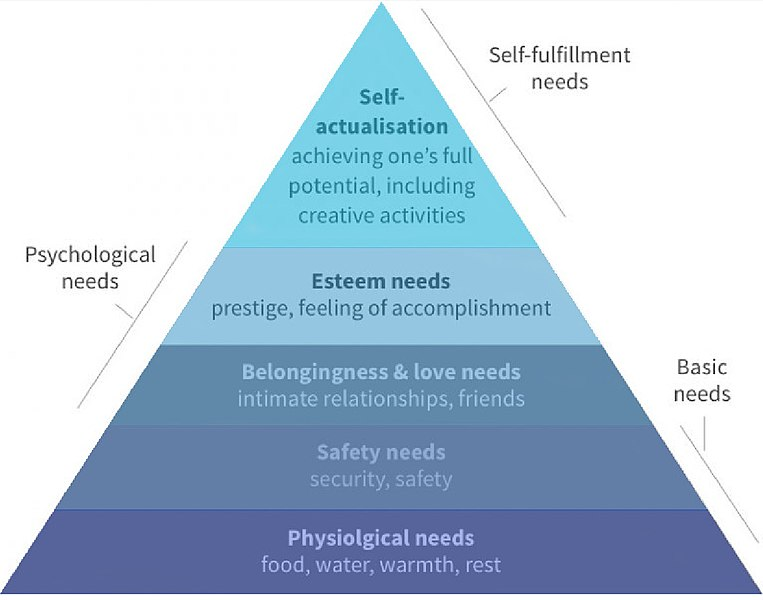

Maslow theorized that humans have several innate needs that were the basis for his theory of motivation on the hierarchy of needs. Furthermore, he believed that the needs are ranked in terms of a hierarchy. Non-humans can possess the lower, more basic needs also, but only humans may possess the higher needs. First, physiological needs are related to survival and these necessities include food, water, elimination, sex, and sleep. Maslow believed that if one of these needs is not achieved, it will rule the individual’s life, and that most humans achieve these needs easily. After one need is met, the individual moves onto the next level. However, Maslow stressed that a person can experience periodic times of hunger or thirst and still move onto higher levels, but the individual’s life cannot be dominated by just one need.

Safety needs appear when physiological needs are fulfilled. These are the needs for structure, order, security, and predictability. Reducing uncertainty is the chief objective at this stage. Individuals are free from danger, fear, and chaos when the safety needs are adequately met. Affiliation is the next level after the physiological and safety needs are attained. This level includes the need for friends, family, identification with a group, and a personally intimate relationship. A person may experience feelings of solitude and emptiness if these needs are not quenched. The esteem needs will follow only if one has achieved the physiological, safety, and belongingness needs. In this stage, approval must come from earned respect and not from fame or social status. Acceptance and self-esteem originate from engaging in activities that are deemed as being socially constructive. An individual may possess feelings of inferiority if the esteem needs are not reached.

If the previous needs are sufficiently met, a person now has the opportunity to become self-actualized. However, self-actualization is an exceptional feat since it so rarely occurs. A person who reaches this stage strives for growth and self-improvement. According to Maslow, the majority of people advance through the hierarchy of needs from the bottom up, in an orderly fashion.

Figure 11.1

The Basic Needs

The ‘physiological’ needs

The needs that are usually taken as the starting point for motivation theory are the so-called physiological drives. Young (1936) in a recent article has summarized the work on appetite in its relation to body needs. If the body lacks some chemical, the individual will tend to develop a specific appetite or partial hunger for that food element. It is most likely that the major motivation would be the physiological needs rather than any others. A person who is lacking food, safety, love, and esteem would most probably hunger for food more strongly than for anything else. If all the needs are unsatisfied, and the organism is then dominated by the physiological needs, all other needs may become simply non-existent or be pushed into the background.

The safety needs

If the physiological needs are relatively well gratified, there then emerges a new set of needs, which we may categorize roughly as the safety needs. All that has been said of the physiological needs is equally true, although to a lesser degree, of these desires. The organism may equally well be wholly dominated by them. They may serve as the almost exclusive organizers of behavior, recruiting all the capacities of the organism in their service, and we may then fairly describe the whole organism as a safety-seeking mechanism. Again, we may say of the receptors, the effectors, of the intellect and the other capacities that they are primarily safety-seeking tools. Again, as in the hungry person, we find that the dominating goal is a strong determinant not only of their current world-outlook and philosophy but also of their philosophy of the future. Practically everything looks less important than safety, (even sometimes the physiological needs which are being satisfied, are now underestimated). A person, in this state, if it is extreme enough and chronic enough, may be characterized as living almost for safety alone.

Another indication of the child’s need for safety is their preference for some kind of undisrupted routine or rhythm. They seem to want a predictable, orderly world. For instance, injustice, unfairness, or inconsistency in the parents seems to make a child feel anxious and unsafe. This attitude may be not so much because of the injustice per se or any particular pains involved, but rather because this treatment threatens to make the world look unreliable, or unsafe, or unpredictable. Young children seem to thrive better under a system which has at least a skeletal outline of rigidity, in which there is a schedule of a kind, some sort of routine, something that can be counted upon, not only for the present but also far into the future. Perhaps one could express this more accurately by saying that the child needs an organized world rather than an unorganized or unstructured one.

The central role of the parents and the family setup are indisputable. Quarreling, physical assault, separation, divorce or death within the family may be particularly terrifying. Also parental outbursts of rage or threats of punishment directed to the child, calling them names, speaking to them harshly, shaking them, handling them roughly, or actual physical punishment sometimes elicit such total panic and terror in the child that we must assume more is involved than the physical pain alone. While it is true that in some children this terror may represent also a fear of loss of parental love, it can also occur in completely rejected children, who seem to cling to the hating parents more for sheer safety and protection than because of hope of love.

Confronting a child with new, unfamiliar, strange, unmanageable stimuli or situations will too frequently elicit the danger or terror reaction, as for example, getting lost or even being separated from the parents for a short time, being confronted with new faces, new situations or new tasks, the sight of strange, unfamiliar or uncontrollable objects, illness or death. Particularly at such times, the child’s frantic clinging to his parents is eloquent testimony to their role as protectors (quite apart from their roles as food-givers and love-givers). From these and similar observations, we may generalize and say that the average child in our society generally prefers a safe, orderly, predictable, organized world, which they can count on and in which unexpected, unmanageable or other dangerous things do not happen, and in which, in any case, they have all-powerful parents who protect and shield them from harm. That these reactions may so easily be observed in children is in a way a proof of the fact that children in our society, feel too unsafe. Children who are raised in an unthreatening, loving family do not ordinarily react as we have described above (Shirley, 1942). In such children the danger reactions are apt to come mostly to objects or situations that adults too would consider dangerous.

Other broader aspects of the attempt to seek safety and stability in the world are seen in the very common preference for familiar rather than unfamiliar things, or for the known rather than the unknown. The tendency to have some belief system or world-philosophy that organizes the universe and the people in it into some sort of satisfactorily coherent, meaningful whole is also in part motivated by safety-seeking. Here too we may list science and philosophy in general as partially motivated by the safety needs (we shall see later that there are also other motivations to scientific, philosophical or religious endeavors). Otherwise the need for safety is seen as an active and dominant mobilizer of the organism’s resources only in emergencies, e.g. war, disease, natural catastrophes, crime waves, social disorganization, neurosis, brain injury, chronically bad situation.

The love needs

If both the physiological and the safety needs are fairly well gratified, then there will emerge the love and affection and belongingness needs, and the whole cycle already described will repeat itself with this new center. Now the person will feel keenly, as never before, the absence of friends, or a partner or children. They will hunger for affectionate relations with people in general, namely, for a place in their group, and they will strive with great intensity to achieve this goal. They will want to attain such a place more than anything else in the world and may even forget that once, when they were hungry, they sneered at love.

In our society the thwarting of these needs is the most commonly found core in cases of maladjustment and more severe psychopathology. Love and affection, as well as their possible expression in sexuality, are generally looked upon with ambivalence and are customarily hedged about with many restrictions and inhibitions. Practically all theorists of psychopathology have stressed thwarting of the love needs as basic in the picture of maladjustment. Many clinical studies have therefore been made of this need and we know more about it perhaps than any of the other needs except the physiological ones (Maslow & Mittelemann, 1941).

One thing that must be stressed at this point is that love is not synonymous with sex. Sex may be studied as a purely physiological need. Ordinarily sexual behavior is multi-determined, that is to say, determined not only by sexual but also by other needs, chief among which are the love and affection needs. Also not to be overlooked is the fact that the love needs involve both giving and receiving love (Maslow, 1942; Plant, 1937).

The esteem needs

All people in our society (with a few pathological exceptions) have a need or desire for a stable, firmly based, (usually) high evaluation of themselves, for self-respect, or self-esteem, and for the esteem of others. By firmly based self-esteem, we mean that which is soundly based upon real capacity, achievement and respect from others. These needs may be classified into two subsidiary sets. These are, first, the desire for strength, for achievement, for adequacy, for confidence in the face of the world, and for independence and freedom (Fromm, 1941). Secondly, we have what we may call the desire for reputation or prestige (defining it as respect or esteem from other people), recognition, attention, importance or appreciation. These needs have been relatively stressed by Alfred Adler and his followers, and have been relatively neglected by Freud and the psychoanalysts. More and more today however there appears to be widespread appreciation of their central importance.

Satisfaction of self-esteem leads to feelings of self-confidence, worth, strength, capability and adequacy of being useful and necessary in the world. But thwarting these needs produces feelings of inferiority, of weakness and of helplessness. These feelings in turn give rise to either basic discouragement or else compensatory or neurotic trends. An appreciation of the necessity of basic self-confidence and an understanding of how helpless people are without it, can be easily gained from a study of severe traumatic neurosis (Kardiner, 1941; Maslow, 1939).

The need for self-actualization

Even if all these needs are satisfied, we may still often (if not always) expect that a new discontent and restlessness will soon develop, unless the individual is doing what they are fitted for. A musician must make music, an artist must paint, a poet must write, if they are to be ultimately happy. What a person can be, they must be. This need we may call self-actualization.

This term, first coined by Kurt Goldstein, is being used in this chapter in a much more specific and limited fashion. It refers to the desire for self-fulfillment, namely, to the tendency for them to become actualized in what they are potentially. This tendency might be phrased as the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming. The specific form that these needs will take will of course vary greatly from person to person. In one individual it may take the form of the desire to be an ideal mother, in another it may be expressed athletically, and in still another it may be expressed in painting pictures or in inventions. It is not necessarily a creative urge although in people who have any capacities for creation it will take this form. The clear emergence of these needs rests upon prior satisfaction of the physiological, safety, love and esteem needs.

Image 11.3

Future Characteristics of the Basic Needs

The degree of fixity of the hierarchy of basic needs

We have spoken so far as if this hierarchy were a fixed order but actually it is not nearly as rigid as we may have implied. It is true that most of the people with whom we have worked have seemed to have these basic needs in about the order that has been indicated. However, there have been a number of exceptions:

1. There are some people in whom, for instance, self-esteem seems to be more important than love. This most common reversal in the hierarchy is usually due to the development of the notion that the person who is most likely to be loved is a strong or powerful person, one who inspires respect or fear, and who is self-confident or aggressive. Therefore such people who lack love and seek it, may try hard to put on a front of aggressive, confident behavior. But essentially they seek high self-esteem and its behavior expresses more as a means-to-an-end than for its own sake; they seek self-assertion for the sake of love rather than for self-esteem itself.

2. There are other, apparently innately creative people in whom the drive to creativeness seems to be more important than any other counter-determinant. Their creativeness might appear not as self-actualization released by basic satisfaction, but in spite of lack of basic satisfaction.

3. In certain people the level of aspiration may be permanently deadened or lowered. That is to say, the less prepotent goals may simply be lost, and may disappear forever, so that the person who has experienced life at a very low level, i.e., chronic unemployment, may continue to be satisfied for the rest of his life if only he can get enough food.

4. The so-called ‘psychopathic personality’ is another example of permanent loss of the love needs. These are people who, according to the best data available (Levy, 1937), have been starved for love in the earliest months of their lives and have simply lost forever the desire and the ability to give and to receive affection (as animals lose sucking or pecking reflexes that are not exercised soon enough after birth).

5. Another cause of reversal of the hierarchy is that when a need has been satisfied for a long time, this need may be under-evaluated. People who have never experienced chronic hunger are apt to underestimate its effects and to look upon food as a rather unimportant thing. If they are dominated by a higher need, this higher need will seem to be the most important of all. It then becomes possible, and indeed does actually happen, that they may, for the sake of this higher need, put themselves into the position of being deprived of a more basic need. We may expect that after a long-time deprivation of the more basic need there will be a tendency to reevaluate both needs so that the more pre-potent need will actually become consciously prepotent for the individual who may have given it up very lightly. Thus, a person who has given up their job rather than lose their self-respect, and who then starves for six months or so, may be willing to take their job back even at the price of losing their self-respect.

6. Another partial explanation of apparent reversals is seen in the fact that we have been talking about the hierarchy of prepotency in terms of consciously felt wants or desires rather than of behavior. Looking at behavior itself may give us the wrong impression. What we have claimed is that the person will want the more basic of two needs when deprived of both. There is no necessary implication here that they will act upon their desires. Let us say again that there are many determinants of behavior other than the needs and desires.

7. Perhaps more important than all these exceptions are the ones that involve ideals, high social standards, high values and the like. With such values people become martyrs; they give up everything for the sake of a particular ideal, or value. These people may be understood, at least in part, by reference to one basic concept (or hypothesis) which may be called ‘increased frustration-tolerance through early gratification.’ People who have been satisfied in their basic needs throughout their lives, particularly in their earlier years, seem to develop exceptional power to withstand present or future thwarting of these needs simply because they have strong, healthy character structure as a result of basic satisfaction. They are the ‘strong’ people who can easily weather disagreement or opposition, who can swim against the stream of public opinion and who can stand up for the truth at great personal cost. It is just the ones who have loved and been well loved, and who have had many deep friendships who can hold out against hatred, rejection or persecution.

Degree of relative satisfaction

So far, our theoretical discussion may have given the impression that these five sets of needs are somehow in a stepwise, all-or-none relationship to each other. We have spoken in such terms as the following: “If one need is satisfied, then another emerges.” This statement might give the false impression that a need must be satisfied 100 per cent before the next need emerges. In actual fact, most members of our society who are typical are partially satisfied in all their basic needs and partially unsatisfied in all their basic needs at the same time. A more realistic description of the hierarchy would be in terms of decreasing percentages of satisfaction as we go up the hierarchy of prepotency, For instance, say the average citizen is satisfied perhaps 85 per cent in their physiological needs, 70 per cent in their safety needs, 50 per cent in his love needs, 40 per cent in their self-esteem needs, and 10 per cent in their self-actualization needs.

Unconscious character of needs

On the whole, however, in the average person, the needs are more often unconscious rather than conscious. It is not necessary at this point to overhaul the tremendous mass of evidence which indicates the crucial importance of unconscious motivation. It would by now be expected that unconscious motivations would on the whole be rather more important than the conscious motivations. What we have called basic needs are very often unconscious and likely become conscious through increased self-awareness.

Cultural specificity and generality of needs

Basic needs will vary across cultures. However, it is the common experience of anthropologists that people, even in different societies, are much more alike than we would think from our first contact with them, and that as we know them better we seem to find more and more of this commonness, we then recognize the most startling differences to be superficial rather than basic, e. g., differences in style of hair-dress, clothes, tastes in food, etc. Our classification of basic needs is in part an attempt to account for this unity behind the apparent diversity from culture to culture. No claim is made that it is ultimate or universal for all cultures.

Multiple motivations of behavior

These needs must be understood not to be exclusive or single determiners of certain kinds of behavior. An example may be found in any behavior that seems to be physiologically motivated, such as eating, or sexual play or the like. Clinical psychologists have long since found that any behavior may be a channel through which various determinants flow. Or to say it in another way, most behavior is multi-motivated.

Any behavior tends to be determined by several or all of the basic needs simultaneously rather than by only one of them. Eating may be partially for the sake of filling the stomach, and partially for the sake of comfort and amelioration of other needs. One may make love not only for pure sexual release, but also to convince one’s self of one’s sexuality, or to make a conquest, to feel powerful, or to win more basic affection. For example, it would be possible (theoretically if not practically) to analyze a single act of an individual and see in it the expression of their physiological needs, their safety needs, their love needs, their esteem needs and self-actualization.

Image 11.4

Summary

There are at least five sets of goals, which we may call basic needs. These are physiological, safety, love, esteem, and self-actualization. In addition, we are motivated by the desire to achieve or maintain the various conditions upon which these basic satisfactions rest and by certain more intellectual desires.

These basic goals are related to each other, being arranged in a hierarchy of prepotency. This means that the most dominant goal will monopolize consciousness and will organize the recruitment of the various capacities of the organism. The less prepotent needs are minimized, even forgotten or denied. But when a need is fairly well satisfied, the next prepotent (‘higher’) need emerges, in turn to dominate the conscious life and to serve as the center of organization of behavior, since gratified needs are not active motivators.

Thus, humans are perpetually wanting animals. Ordinarily the satisfaction of these wants is not altogether mutually exclusive, but only tends to be. The typical member of our society is most often partially satisfied and partially unsatisfied in all of their wants. The hierarchy principle is usually empirically observed in terms of increasing percentages of non-satisfaction as we go up the hierarchy. Reversals of the average order of the hierarchy are sometimes observed. Also it has been observed that an individual may permanently lose the higher wants in the hierarchy under special conditions. There are not only ordinarily multiple motivations for usual behavior, but in addition many determinants other than motives.

Any thwarting or possibility of thwarting these basic human goals, or danger to the defenses which protect them, or to the conditions upon which they rest, is considered to be a psychological threat. With a few exceptions, all psychopathology may be partially traced to such threats. A basically thwarted person may actually be defined as a ‘sick’ person, if we wish. It is such basic threats which bring about the general emergency reactions.

Criticisms of Maslow’s Theory of Motivation

(McLeod, 2017)

The most significant limitation of Maslow’s theory concerns his methodology. Maslow formulated the characteristics of self-actualized individuals from undertaking a qualitative method called biographical analysis. He looked at the biographies and writings of 18 people he identified as being self-actualized. From these sources he developed a list of qualities that seemed characteristic of this specific group of people, as opposed to humanity in general. It is extremely difficult to empirically test . Maslow’s concept of self-actualization in a way that causal relationships can be established. From a scientific perspective there are numerous problems with this particular approach. First, it could be argued that biographical analysis as a method is extremely subjective as it is based entirely on the opinion of the researcher. Personal opinion is always prone to bias, which reduces the validity of any data obtained. Therefore, Maslow’s operational definition of self-actualization must not be blindly accepted as scientific fact.

Furthermore, Maslow’s biographical analysis focused on a biased sample of self-actualized individuals, prominently limited to highly educated white males (such as Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Albert Einstein, William James, Aldous Huxley, Gandhi, and Beethoven). Although Maslow (1970) did study self-actualized females, including Eleanor Roosevelt and Mother Teresa, they comprised a small proportion of his sample. This makes it difficult to generalize his theory to females and individuals from lower social classes or different ethnicities, which leads to questions on population validity of Maslow’s findings.

Another criticism concerns Maslow’s assumption that the lower needs must be satisfied before a person can achieve their potential and self-actualize. This is not always the case, and therefore Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in some aspects has been falsified. Through examining cultures in which large numbers of people live in poverty (such as India), it is clear that people are still capable of higher order needs such as love and belongingness. However, this should not occur, as according to Maslow, people who have difficulty achieving very basic physiological needs (such as food, shelter etc.) are not capable of meeting higher growth needs. Also, many creative people, such as authors and artists (e.g. Rembrandt and Van Gogh) lived in poverty throughout their lifetime, yet it could be argued that they achieved self-actualization.

Psychologists now conceptualize motivation as a pluralistic behavior, whereby needs can operate on many levels simultaneously. A person may be motivated by higher growth needs at the same time as lower level deficiency needs. Contemporary research by Tay & Diener (2011) has tested Maslow’s theory by analyzing the data of 60,865 participants from 123 countries, representing every major region of the world. The survey was conducted 2005-2010. Respondents answered questions about six needs that closely resemble those in Maslow’s model: basic needs (food, shelter); safety; social needs (love, support); respect; mastery; and autonomy. They also rated their well-being across three discrete measures: life evaluation (a person’s view of his or her life as a whole), positive feelings (day-to-day instances of joy or pleasure), and negative feelings (everyday experiences of sorrow, anger, or stress). The results of the study support the view that universal human needs appear to exist regardless of cultural differences. However, the ordering of the needs within the hierarchy was not correct. According to Diener, “Although the most basic needs might get the most attention when you don’t have them, you don’t need to fulfill them in order to get benefits from other loftier needs. Even when we are hungry, for instance, we can be happy with our friends” (as cited in Bauman, 2017, p. 41).

Image 11.5

Educational Implications

(McLeod, 2017)

Maslow’s theory of motivation is also called the theory of hierarchical needs. Maslow’s (1968) has made a major contribution to teaching and classroom management in schools. Rather than reducing behavior to a response in the environment, Maslow (1970) adopts a holistic approach to education and learning. Maslow looks at the complete physical, emotional, social, and intellectual qualities of an individual and how they impact on learning.

Applications of Maslow’s hierarchical needs theory to the work of the classroom teacher are obvious. Before a student’s cognitive needs can be met they must first fulfill their basic physiological needs. For example, a tired and hungry student will find it difficult to focus on learning. Students need to feel emotionally and physically safe and accepted within the classroom to progress and reach their full potential.

Maslow suggests students must be shown that they are valued and respected in the classroom and the teacher should create a supportive environment. Students with a low self-esteem will not progress academically at an optimum rate until their self-esteem is strengthened. Maslow (1971) argued that a humanistic educational approach would develop people who are “stronger, healthier, and would take their own lives into their own hands to a greater extent. With increased personal responsibility for one’s personal life, and with a rational set of values to guide one’s choosing, people would begin to actively change the society in which they lived” (p. 195).

Chapter Discussion Questions:

- Explain the benefits of the theory of human motivation to support student success.

- How would you summarize the theory of human motivation?

- How would you use the theory of human motivation to support your students?

- How is equity related to the theory of human motivation?

ATTRIBUTIONS

Image 11.1: “Motivation -what is it” by Wikipedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Image 11.2: “Abraham Maslow ” is in the Public Domain

Image 11.3: ” Education is the light of society. Without a free and equitable education system, a society will never civilize itself above Maslow’s basic needs.” by Ken Whytock is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Image 11.4: “Quotation about the motivation of teacher feedback” by Ken Whytock is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Image 11.5: “Middle School Students Eating Lunch” by Peter Howard is in the Public Domain, CC0

Video 11.1: “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” by Sprouts Schools

Video 11.2: “Daniel Pink – Motivation ” by The Brainwaves Video Anthology

REFERENCES

Adler, A. (1938). Social interest. London: Faber & Faber.

Bauman, S. (2017). Break open the sky: Saving our faith from a culture of fear. New York, NY: Multnomah.

Cannon, W. B. (1932). Wisdom of the body. New York, NY: Norton.

Freud, S. (1933). New introductory lectures on psychoanalysis. New York, NY: Norton.

Fromm, E. (1941). Escape from freedom. New York, NY: Farrar and Rinehart.

Goldstein, K. (1939). The organism. New York, NY: American Book Co.

Kardiner, A. (1941). The traumatic neuroses of war. New York, NY:

Hoeber. Levy, D. M. (1937). Primary affect hunger. Psychiat., 94, 643-652.

Maslow, A. H. (1939). Dominance, personality and social behavior in women. Journal of Social Psychology, 10, 3-39.

Maslow, A. H. (1942). The dynamics of psychological security-insecurity. Character & Pers ., 10, 331-344.

Maslow, A. H. (1943a). A preface to motivation theory. Psychosomatic Med., 5, 85-92.

Maslow, A. H. (1943b). Conflict, frustration, and the theory of threat. Journal of Abnormal (Soc.) Psychol., 38, 81-86.

Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a Psychology of being. New York, NY: D. Van Nostrand Company.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Maslow, A. H. (1971). The farther reaches of human nature. New York, NY: Viking.

Maslow, A. H., & Mittelemann, B. (1941). Principles of abnormal psychology. New York, NY: Harper & Bros.

McLeod, S. A. (2017). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Retrieved from www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

Murray, H., Barrett, W., Homburger, E., Langer, W., Mereel, H. S., Morgan, C. D., …Wolf, R. E. (1938). Explorations in personality. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Plant, J. (1937). Personality and the cultural pattern. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund.Page 116

Shirley, M. (1942). Children’s adjustments to a strange situation. Journal of Abnormal Soc. Psychol., 37, 201-217.

Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 354-365.

Tolman, E. C. (1932). Purposive behavior in animals and men. New York, NY: Century. Wertheimer, M. (n.d.). Unpublished lectures at the New School for Social Research.

Young, P. T. (1936). Motivation of behavior. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

ADDITIONAL READING

Credible Articles on the Internet

Boeree, C. G. (2006). Abraham Maslow. Retrieved from http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/Maslow.html

Burleson, S., & Thoron, A. (2009). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and its relation to learning and achievement. Retrieved from https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/WC/WC15900.pdf

Gawel, J. E. (1997). Herzberg’s theory of motivation and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/files/herzberg.html

Green, C. D. (2000). Classics in the history of psychology. Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm

Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles

Gambrel, P. A., & Cianci, R. (2003). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Does it apply in a collectivist culture. Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 143-161.

Gordon Rouse, K., A. (2004). Beyond Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: What do people strive for? Performance Improvement, 43(10), 27-31.

Hagerty, M. R. (1999). Testing Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: National quality-of-life across time. Social Indicators Research, 46(3), 249-271.

Milheim, K. L. (2012). Towards a better experience: Examining student needs in the online classroom through Maslow’s hierarchy of needs model. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 8(2), 159.

Vanagas, R., & Raksnys, A. V. (2014). Motivation in public sector- motivational alternatives in the Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Public Policy and Administration Research Journal, 13(2). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13165/VPA-14-13-2-10

Books at Dalton State College Library

Goble, F. G. (1978). The third force: The psychology of Abraham Maslow. New York, NY: Grossman.

Maslow, A. H. (1999). Toward a psychology of being (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley & Sons.

Sheehy, N. (2004). Fifty key thinkers in psychology. New York, NY: Routledge.

Videos and Tutorials

Child Development Theorists: Freud to Erikson to Spock and Beyond. Retrieved from Films on Demand database.