13 Critical Pedagogy

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify key elements of social reconstructionism and critical pedagogy

- Explain the major tenets of critical pedagogy and how they can be utilized to support instruction

- Summarize the criticisms of critical pedagogy and educational implications

- Explain major tenets of Critical Race Theory

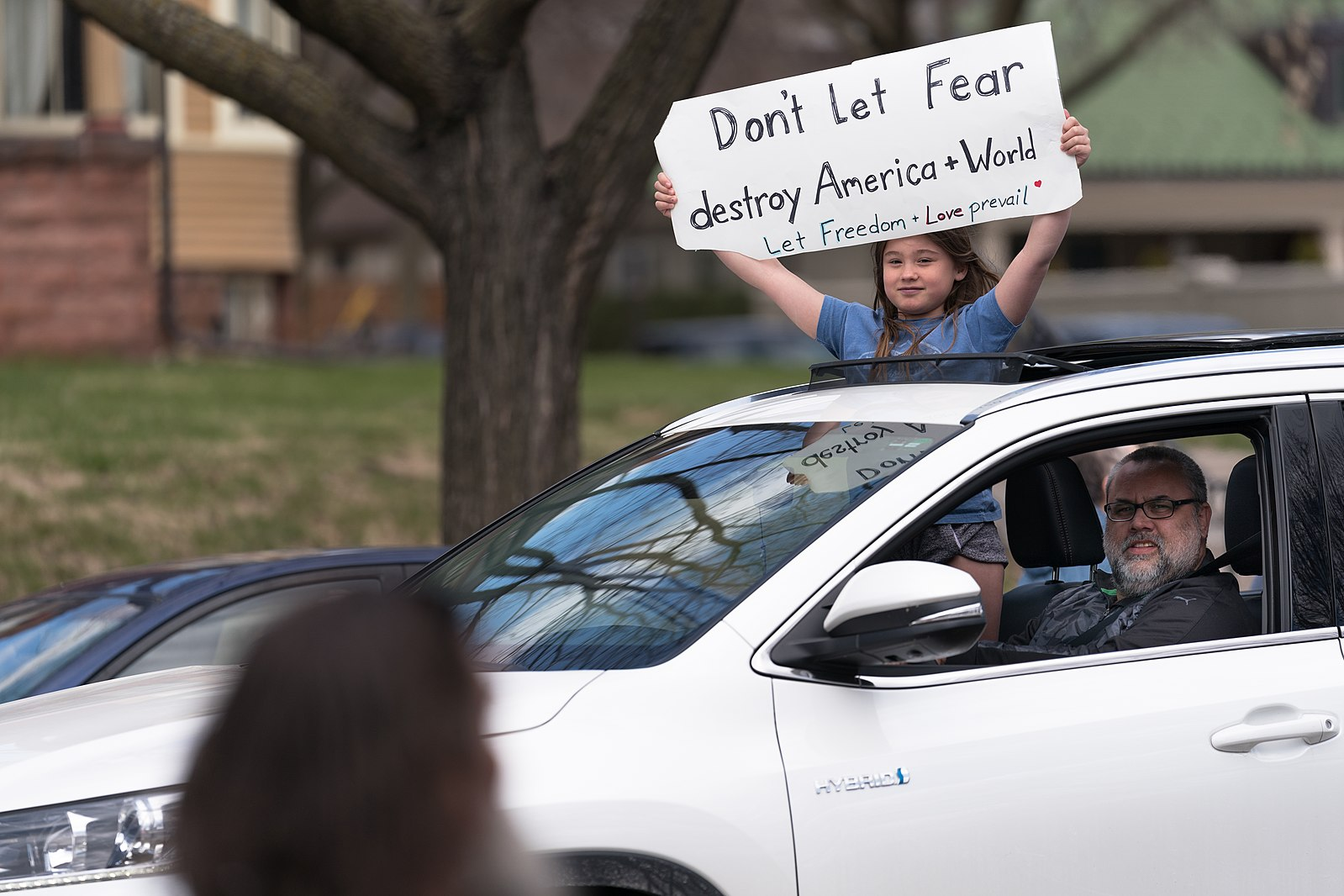

Image 13.1

Scenario:

Ms. Barrows woke in the middle of the night to rethink her unit on ratios. Students seemed totally uninterested. She thought back to her own schooling and recalled the teacher who made the difference in her schooling, the one who encouraged the students to consider different points of view on contemporary and historic events and develop critical questions that connected to their own lives. Ms. Barrows recalled how she and her classmates had conducted a role play and hotly debated the issues. The students ultimately wrote letters to their city council about the issues. They felt they were actually doing something about it. It did not feel like school work, and it ultimately drew Ms. Barrows to the teaching profession. Through the years, Ms. Barrows had become the “expert teacher” who mastered her content area with great pride. Her lesson plans had not changed much from year to year, and they were becoming rather tiring, even to her.

Thinking about this special teacher, Ms. Barrows knew her learning activities needed to engage the students with something meaningful, something they would care about. Thinking about the legacy of the institutions that informed the social fabric upon which her students exist, it became clear that provisioning an environment where students could analyze disparities and act on them would provide a relevant topic in which to explore ratios.

After a long night of contemplation and rumination, she began to plan a lesson on income inequality, showing salaries of famous athletes, rappers, politicians, social media celebrities, teachers, construction and restaurant workers. She found some Youtube videos profiling these individuals to draw students in at the start. She built in places for students to express their ideas on the topic and feel the impact on their own lives. She took students through the concepts of ratios and created relevant word problems for students to solve. Depending on the students and the learning experience, Ms. Barrows knew she wanted to create space for students to come up with next steps, not just with math but with this topic of income inequality. She knew she had to see where the learning experience took them, that she had to open herself up to this uncertainty, that her students needed to decide what was important to them and co-create next steps in the learning.

As you read about critical pedagogy, consider how important it is for educators to know what is meaningful to their students, and how this involves getting to know their students. Students are not blank slates. They are full of rich stories and experiences, and effective critical educators seek to engage those stories and experiences.These educators know that learning must be co-constructed and that they need to engage students in things they care about.

Image 13.2

What kind of questions could such a photo elicit? Consider the rich discussion possibilities on the concepts of freedom, fear and love.

INTRODUCTION

What is Social Reconstructionism?

Social reconstructionism was founded as a response to the atrocities of World War II and the Holocaust to assuage human cruelty. Social reform in response to helping prepare students to make a better world through instilling liberatory values. Critical pedagogy emerged from the foundation of the early social reconstructionist movement.

What is Critical Pedagogy?

Critical pedagogy is the application of critical theory to education. For critical pedagogues, teaching and learning is inherently a political act and they declare that knowledge and language are not neutral, nor can they be objective. Therefore, issues involving social, environmental, or economic justice cannot be separated from the curriculum. Critical pedagogy’s goal is to emancipate marginalized or oppressed groups by developing, according to Paulo Freire, conscientização, or critical consciousness in students.

Critical pedagogy de-centers the traditional classroom, which positions teachers at the center. The curriculum and classroom with a critical pedagogy stance is student-centered and focuses its content on social critique and political action. Such educators propose a liberatory practice, in which the central purpose of educators is to liberate and to humanize students in today’s schools so that they can reach their full potential. Using power analyses, they seek to undo structural societal inequities through the work of schooling. They emphasize the importance of the relationship between educators and students, as well as the co-creation of knowledge. Education is a way to freedom.

Major influences on the formation of critical pedagogy:

John Dewey, W.E.B. Dubois, Carter G. Woodson, Myles Horton, Herbert Kohl, Paulo Freire, Maxine Greene, Henry Giroux, Samuel Bowles, Herbert Gintis, Martin Carnoy, Michael Apple, bell hooks, Jean Anyon, Stanley Aronowitz, Peter McLaren, Donaldo Macedo, Michelle Fine

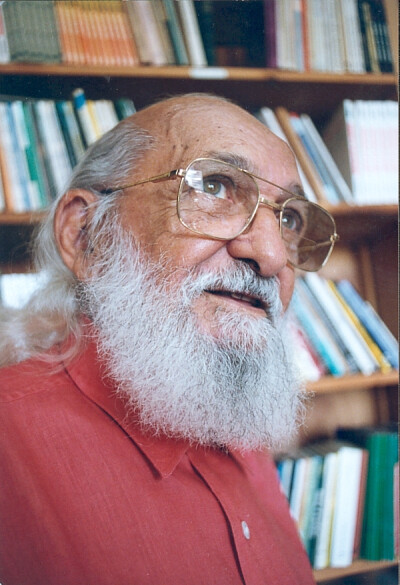

Image 13.3

Paulo Freire: 1921-1997

Paulo Freire was born in 1921 in the northeastern city of Recife in Brazil’s poorest region, Pernambuco. Much of Brazil’s citizenry were impoverished and illiterate, and run by a small group of wealthy landowners. Freire’s family was middle class but experienced hardships, especially during the Great Depression. His father died in 1934 and Paulo struggled to support his family and finish his studies. After completing his studies, Freire went on to work in a state-sponsored literacy campaign. It was here that Freire began to interact with the peasant struggle. Freire was nominated to lead Brazil’s National Commission of Popular Culture in 1963 under the liberal-populist government of João Goulart whose government created many policies to assist the poor such as mass literacy campaigns. As is often the case, these reforms were opposed by the upper classes who eventually supported the military coup which overthrew the government and installed a right-wing dictatorship. Freire was imprisoned for his political leanings and role with literacy reforms. Upon his release from prison, Freire went into exile for a number of years, returning in 1980 to become the secretary of education for the state of São Paulo.

Image 13.4

It was during his exile that Freire wrote the book which would make him globally famous. Pedagogy of the Oppressed was published in Portuguese in 1968, and in English in 1970 has had tremendous influence on educators worldwide. As people struggled for civil rights across the globe in the 1970s, Freire’s work had popular appeal. “However, [Freire’s] enduring popularity and influence attests to another, even more intractable context: even as many more people around the world have access to education, schooling everywhere remains intertwined with systems of oppression, including racism and capitalism, and traditional models of top-down education don’t work well for everyone” (Featherstone).

Freire’s critique of education was replicated and perpetuated the classist inequitable society, feeding oppressed workers into the capitalist structure. He wrote that our educational systems have the potential to liberate or oppress their students, and in the process humanize or dehumanize their students. Freire argues that people live one of two ways: humanized or dehumanized, and that this is the central problem of humankind. Freire argued that people become dehumanized because of unjust systems, systems that provide access to some and not to others.

Freire highlighted the power dynamic between teacher and students and critiqued the power that teachers held with the supposed “truth” of their opinions and curriculum (what should be taught in a particular discipline), as well as their evaluation of students. Freire critiques the traditional frame of the teacher as the authority or expert and the students as “empty vessels” or sometimes referred to as “blank slates.”

Freire coined the term “the banking method” for the way in which traditionally teachers deposit information into their students, as if they are empty vessels or receptacles. Students become oppressed through this system of education where they learn to memorize and regurgitate the facts deposited in them by their teachers. Students in these systems, in fact, come to expect such oppression and are in fact upset when their teachers do not take on the expert role. Freire believed that the traditional model creates a kind of ignorance where students are unable to critique knowledge and power, and are in fact dependent on their expert teachers.

In fact, Freire believed this mentality makes students vulnerable to oppression in their lives moving forward: at work, school, and in society at large. Freire believes it is critical for students to participate in this process of learning, to liberate themselves.

“For apart from inquiry, apart from praxis, men cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through invention and re-invention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry men pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other” (Freire).

Freire proposes to overthrow the traditional hierarchy in the classroom. Liberation and humanization result from what Freire referred to as “dialogical” interaction between teachers and students and a co-creation of knowledge and learning. He came to understand that true liberation comes about through dialogue between the teacher and student, where they learn from each other.

“The more students work at storing the deposits entrusted to them, the less they develop the critical consciousness which would result from their intervention in the world as transformers of that world. The more completely they accept the passive role imposed on them, the more they tend to adapt to the world as it is and to the fragmented view of reality deposited in them” (Freire).

This pedagogy creates an environment of mutual respect, love, and understanding and leads students toward liberation. Freire believed that it is important that oppressed people define the world in their own terms. It is only with this common language (defined by the oppressed) that dialogue can begin. The concept of a superiority or hierarchy of educators such as a teacher has no place in Freire’s classroom. Dialogue must engage everyone equally.

bell hooks: 1952- 2021

“To educate as the practice of freedom is a way of teaching that anyone can learn. That learning process comes easier to those of us who teach who also believe there is an aspect to our vocation that is sacred; who believe that our work is not merely to share information but to share in the intellectual and spiritual growth of our students. To teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin.” (hooks)

bell hooks was born with the name Gloria Jean Watkins on September 25, 1952 in a segregated town of Hopkinsville, Kentucky to a working-class African American family. She was one of six children. Her mother worked as a maid for a White family and her father was a janitor. Eventually she took on the name of her great-grandmother, to honor her female lineage, spelling it in all lowercase letters to focus attention on her message rather than herself. She has written many books, and initially famous for her work as a Black post modern queer feminist and her first published work Aint I a Woman?: Black Women and Feminism in 1981. She taught English and Ethnic Studies for many years at a variety of institutions of higher learning. She wrote books on many topics including multiple forms of oppression, racism, patriarchy, Black men, masculinity, self-help, engaged pedagogy, personal memoirs, sexuality, feminism, and identity.

bell hooks grew up in segregated schools which provided shining examples of what schooling could be. Bell loved her Black teachers and describes school as a place of ecstasy and joy. Her black teachers were committed to nurturing intellect and activism among their Black students. They considered learning especially for Black people in the US, an important political act, a way to counter White racist colonization. These teachers made it their mission to know their parents and communities. Bell describes how these missionary Black teachers saw this important work as uplifting the race and provided a level of caring for the whole child, in order for that child to survive in a racist society. Bell’s disillusionment with education began with school integration, when she was bussed across town to White schools, where schooling was about ideas and no longer the whole person. She continued to feel disillusioned when she entered higher education.

hooks describes Paulo Friere as a mentor for he embraced the idea that learning could be liberatory. At a time when hooks had become quite disillusioned with education, Freire gave her hope and the confidence to transgress as an educator. She recalled “Finding Freire in the midst of that estrangement was crucial to my survival as a student” (p. 17). All the things Freire said about the banking method and traditional education complimented her ideas about what education should and should not be. hooks desired to co-create learning spaces with her students, to do away with the idea of the dictatorial teacher as an all-knowing expert. She passionately believed that learning should be engaging and ‘never boring,’ and without preconceived set agendas. Creating this excitement and engagement was dependent on knowing each other through dialogue in the classroom. The teacher must make every student feel valued and recognize that everyone in the classroom affects the dynamic.

The Vietnamese Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, was another major influence for hooks particularly regarding health and well-being. Self-actualization can not occur without self-care. Hooks’ holistic concept of engaged pedagogy centers care and healing in the process of learning. Thich Nhat Hanh was concerned with the whole body, more than just the mind (on which Freire primarily focused) according to bell hooks. This wholeness includes mind, body and spirit and emphasizes well-being, a somewhat radical notion in academia.

Video 13.1

Bettina Love: c. 1981-present

“When you understand how hard it is to fight for educational justice, you know that there are no gimmicks; you know this to be true deep down in your soul, which brings both frustration and determination. Educational Justice is going to take people power, driven by the spirit and ideas of the folx who have done the work of anti-racism before: abolitionists…this endless, and habitually thankless, job of radical collective freedom-building is an act of survival, but we who are dark want to do more than survive: we want to thrive. A life of survival is not really living” (Love, p.9).

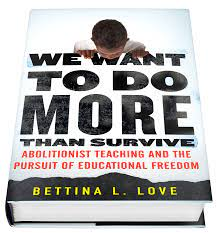

Image 13.6

Bettina Love describes being raised in the 1980s in Rochester, New York. She is an American academic and author, and currently is the William F. Russell Professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, where she has been instrumental in establishing abolitionist teaching in schools. Love defines abolitionist teaching as restoring humanity to children in schools. Abolitionist schooling is based on intersectional justice, anti-racism, love, healing and joy, that all children matter, and specifically affirming that Black Lives Matter.

“Abolitionist teaching asks educators to acknowledge and accept America and its policies as anti-Black, racist, discriminatory and unjust and to be in solidarity with dark folx and poor folx fighting for their humanity and fighting to move beyond surviving. To learn the sociopolitical landscape of their students communities through a historical intersectional justice lens” (Love, p. 12)

Love weaves themes of hip hop into her education praxis. She believes the elements of hip hop have everything to do with self-awareness, critical thinking, and social emotional intelligence. She gives particular attention to knowledge of self. In elementary classrooms, she breaks down the elements of hip hop to work with her students.

Image 13.7

Love is known for advocating for the elimination of the billion-dollar industry of standardized testing, opposing English-only policies and the school-to-prison pipeline, and providing a strong critique of how teachers are prepared. She began her teaching career in a “failing” school in Florida serving low-income immigrant children of many educational and language backgrounds. It was here she began to see how “educational reforms” such as No Child Left Behind (NCLB), the Common Core, and Race to the Top created a sense of hopelessness for students, their families, and staff.

Love unapologetically states that some people should not be teaching because they lack understanding of oppression and oppressed groups who may be sitting in their classrooms (Love, p. 14) and that such teachers should not be teaching Black, Brown, or White children. “Many of these teachers who ‘love all children’ are deeply entrenched in racism, transphobia, classism, rigid ideas of gender, and Islamophobia”(Love, p. 12).

“Teachers must embrace theories such as Critical Race Theory, Settler Colonialism, Black Feminism, dis/ability, critical race studies and other critical theories that have the ability to interrogate anti-Blackness and frame experiences with injustice, focusing the moral compass toward a north star that is ready for a long and dissenting fight for educational justice” (Love, p. 12).

Love points out that when educators do not understand the meaning behind the statement/the movement “Black Lives Matter,” they should not be teaching because they lack a fundamental understanding of systemic and historic racism and how it has impacted Black communities and Black students. Such educators tend to blame the victim instead of the systems, for example blaming the incarcerated father instead of learning about how the justice system has incarcerated disproportionate numbers of Black men.

Critical Race Theory

So, what is Critical Race Theory anyways? Critical Race Theory (CRT) has been used by all sides of the political spectrum as a marketing tool or divisive instrument. In popular media, there is not much accurate information about it. Educators who use CRT believe it is vital to understand how racism operates at all levels in US society, whether by law or custom. Any educator who cares about effectively working with communities of color must spend some time understanding the tenets of this theory, and it behooves anyone who works in US schools to take the time to learn the theory, and especially if they are critiquing it. This is simply a brief introduction and further study is strongly recommended.

CRT was initially developed by Derrick Bell and Alan Freeman who were frustrated by the slow pace of racial reform in the US. In the 1970s many activists and scholars felt that while the Civil Rights Movement had stalled, the law disregarded people of color and lacked an understanding of racism and how deeply embedded it was in US society. CRT provides an analysis in which power structures in the US are based in historic and systemic White supremacy and White privilege which in turn marginalizes people of color. With CRT, the individual racist is irrelevant because society is set up to give more access to White people over others in all areas of society: education, health care, housing, politics, justice etc. This is what is known as White privilege and it has to do with our collective history of inequities upon whose foundation this nation is built. If you do not know much about this history, plan on building your knowledge base through workshops, classes and other resources such as what is listed below:

Video 13.2

Systemic Inequality in America – Resources

|

As leaders and as educators, we should not perpetuate wrongs of the past, and this happens when we do not examine our past and do not account for things that have had a huge impact on our present lives. We need to recognize historical patterns and understand their impact, such as how the people who had access to housing (especially in certain neighborhoods) built their wealth which has compounded and created the income gap that exists between White and Black families (see Video 13.2), and impacts all aspects of society including education. The US educational system has not adequately educated us on this topic and at the same time has become highly politicized regarding topics such as race or inequality which have been presented as antithetical to notions of meritocracy and patriotism. This dichotomy does not serve us well as it prevents us from evolving and moving forward as a nation. As a result, many educators have been coached or mandated to avoid these topics. Generations of US Americans have internalized these stories, unconsciously or consciously, and hence, do not see the oppression unless they are called to examine it, and this is what Critical Race Theory helps us to do.

Image 13.8

What does “White Supremacy” Mean?

White supremacy is a historically based, institutionally perpetuated system of exploitation and oppression of continents, nations, and individuals of color by white individuals and nations of the European continent; for the purpose of maintaining and defending a system of wealth, power and privilege.

The main tenets of Critical Race Theory (CRT) are:

- Racism is deeply embedded in all aspects of US society. The power structure is based in White supremacy and privilege. CRT rejects myths of meritocracy and liberalism because they ignore systemic and historic inequities (for example: meritocracy doesn’t add up when some people have been accumulating generational wealth due to historic racism for many decades. Check out resources above; educate yourself!

- Intersectionality: recognizes a multidimensionality of oppressions including race, sex, class, gender, sexual orientation and how in combination, these play out in a variety of settings. CRT seeks to recognize all oppressions and how they intersect with race.

- Counter narratives challenge the dominant narrative and give voice to those who have been silenced by white supremacy. Their stories are critical to centering the experiences of people of color.

- There is a commitment to Social Justice to end all forms of oppression.

While CRT started in the legal field, it has spread to other disciplines such as education.

When applying CRT to public K-12 education, one must consider:

- Who are our teachers?

- Who are our students?

- What is in our curriculum? Who created it? Who is promoted in the curriculum? Which voices are centered? Which voices are left out? Do they not matter?

- Who gets promoted in our schools?

- Who tests well? Who gets into TAG and honors courses?

- Who sits on our school boards? Who are our educational leaders?

- How are schools funded?

- Whose language is promoted? Whose language is left out and what is the impact of that?

- How is success measured? Grading for what? Whose values? Who decides?

- Who is made to feel that they belong? Who does not belong?

- Who typically gets the best prepared teachers?

- Who gets college degrees, masters degrees, and how recently?

- Does race correlate with any of this? (a fundamental question when using a CRT lens)

How do the answers to all these questions help you to think about CRT as it applies to our educational system? If you do not know how race correlates, you probably will not understand CRT. Critical educators would recommend that you deepen your understanding of how race is so embedded in our institutions and our history, and specifically our educational system, which has clear repercussions for how our society is ultimately structured, and who becomes our political, economic, and social leaders. In order to live in a more just society, critical educators want our students to wrestle with these questions, and fight for a more just future. They want the learning to move beyond the classroom and connect with the lives and challenges of our students. Paulo Freire, bell hooks, Bettina Love, Malcolm X, Dr. Martin Luther King and many others have said this will be a fight and a struggle that will likely not be realized in your own lifetimes. When you understand this, you can grasp the enormous potential and responsibility of educators on a daily basis in the United States.

Criticism of CRT

Critical Race Theory very recently has become a source of much debate across the country, somewhat to the surprise of people who have been studying these issues for years. “Fox News has mentioned ‘critical race theory’ 1300 times in less than four months. Why? Because critical race theory (CRT) has become a new bogeyman for people unwilling to acknowledge our country’s racist history and how it impacts the present” (Rashawn Ray and Alexandra Gibbons, Brookings Institute). NBC News reported that Critical Race Theory is not actually taught in K-12 education but due to the negative attention it is getting, educators are weary of using certain authors, teaching about systemic racism or on a variety of historic and social topics. Most people critiquing CRT do not seem to understand what the theory actually stands for, and have framed it as a divisive framework. Again, it is important for all educators to understand what the theory stands for, and that is not taught in US schools. This debate continues to highlight how divided the country is on race and racism, as is brought into focus through the debate over the phrase “Black Lives Matter.”

Watch these clips about the Critical Race Theory debate:https://www.mediamatters.org/fox-news/fox-news-obsession-critical-race-theory-numbers https://www.cbsnews.com/news/critical-race-theory-teachers-union-honest-history https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/teaching-critical-race-theory-isn-t-happening-classrooms-teachers-say-n1272945 |

Image 13.9

ATTRIBUTIONS

Image 13.1 “Fist Typography” by GDJ is in the Public Domain, CC0

Image 13.2 “Liberate Minnesota Protest” by Wikipedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image 13.3 “Paulo Freire” by Flickr is in the Public Domain

Image 13.4 “Income Inequality” is in the Public Domain

Image 13.5 “As More People of color Raise their consciousness” by Flickr is in the Public Domain

Image 13.5 “We want to do more than survive” by Bettina Love

Image 13.6 “HipHop Mascot” by vectorportal.com is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image 13.7 “Nelson Mandela Quote” by j4p4n open clipart is in thePublic Domain

Image 13.8 “United States Public School for Eskimos – Frank G. Carpenter collection” by is in the Public Domain

Film Clips

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mqrhn8khGLM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kY2C_ATNFEM

https://www.mediamatters.org/fox-news/fox-news-obsession-critical-race-theory-numbers

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/critical-race-theory-teachers-union-honest-history

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/teaching-critical-race-theory-isn-t-happening-classrooms-teachers-say-n1272945

REFERENCES

- Darder, Baltodano, Torres, The Critical Pedagogy Reader, 2nd edition, New York, RoutledgeFalmer,

2009

2. Featherstone , Liza https://www.jstor.org/stable/4028864?mag=paulo-freires-pedagogy-of-the-oppressed-at-fifty

3. Freire, Paulo, 1921-1997. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York :Continuum, 2000.

4. Hooks Bell. Teaching to Transgress : Education As the Practice of Freedom, Routledge 1994.

5. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-oneonta-education106/

6. https://newsreel.org/video/RACE-The-House-We-Live-In

7. https://www.mediamatters.org/fox-news/fox-news-obsession-critical-race-theory-numbers

8. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/15/books/bell-hooks-dead.html

9. Ladson-Billings, Gloria; Tate, William F, IV. Towards a Critical Race Theory of Education, Teachers College Record, Vol. 97, Iss. 1, (Fall 1995): 47.

10. Love, Bettina L. We Want to Do More Than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom. Boston, Massachusetts, Beacon Press, 2019.

11. McCausland, P. 2021. Teaching critical race theory isn’t happening in classrooms, teachers say in survey. NBC News, July 1.

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/teaching-critical-race-theory-isn-t-happening-classrooms-teachers-say-n1272945

12. O’Kane, C. 2021. Head of teachers union says critical race theory isn’t taught in schools, vows to defend “honest history”. CBS News, July 8.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/critical-race-theory-teachers-union-honest-history/

13. Ray, R., and A. Gibbons. 2021. Why are states banning critical race theory? The Brookings Institution.

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2021/07/02/why-are-states-banning-critical-race-theory/

14. Sawchuck, S. 2021. What Is critical race theory, and why is it under attack?

Education, Week , May 18. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/what-is-critical-race-theory-and-why-is-it-under-attack/2021/05?utm_source=nl&utm_medium=eml&utm_campaign=eu&M=62573086&U=1646756&UUID=cc270896d99989f6b27d080283c5630c

15. Skloot, Rebecca, 1972-. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York :Random House Audio, 2010.