8 Bioecological Model of Human Development

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify key elements of bioecological model

- Explain strategies utilized to implement bioecological model

- Summarize the criticisms of bioecological model and educational implications

- Explain how equity is impacted by bioecological model

- Identify classroom strategies to support the use of bioecological model

- Select strategies to support student success utilizing bioecological model

- Develop a plan to implement the use of bioecological model

Image 7.1

SCENARIO:

Luca had gotten into a fight again and as a result, Mrs. Hughes reached out to request an interpreter to meet with Luca’s parents. Luca was a quiet boy in her fifth grade class but he seemed to get into frequent trouble on the playground. Mrs. Hughes knew that there are often multiple possibilities for a child’s behavior and that she needed more information about the child. Naturally, she had her own observations about Luca in her classroom. But, what was his family like? Where did he live? Did his parents work a lot or were they around to support him? She knew Luca was the son of immigrants and she had met them briefly through an interpreter. She knew she needed to set up another meeting with them before making any decisions about how to proceed with Luca.

Mrs. Hughes understands that there are often multiple reasons for human behavior and that a number of factors are involved. As you learn about Brofenbrenner’s Bioecological Model of Human Development, consider the contexts or layers which may be impacting Luca on the playground.

Take a moment to watch these videos:

Video 7.1: “Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory”

INTRODUCTION

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005), was a Russian-American psychologist. At the age of 6, his family relocated to the United States. Bronfenbrenner attended Cornell University, where he completed his double major in psychology and music. He completed his MA at Harvard University then received his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan. Shortly after that, he was hired as a psychologist in the army doing many assignments for the Office of Strategic Services and the Army Air Corps. In administration and research, he worked as an assistant chief psychologist before he accepted the offer from the University of Michigan to work as an assistant professor in psychology. In 1948, he accepted an offer from Cornell University as a professor in Human Development, Family Studies and Psychology. Urie is world renowned for developing the innate relationship between research and policy on child development.

Human development refers to change over time, and time is typically characterized as chronological age. Age is not the cause of development; it is just a frame of reference. More specifically, development comprises interactions among various levels of functioning, from the genetic, physiological, and neurological to the behavioral, social, and environmental. Human development is a permanent exchange among these levels. And the older the person, the more influence and control the person has over these interactions.

Human developmental science attributes the driving force of development to so-called proximal processes: stimulating, regular face-to-face interactions over extended periods with people, objects, or symbols, which promote effective biological, psychological, and social development. For example, parents influence and shape their children through parenting behaviors, role modeling, and encouraging certain behaviors and activities for their children.

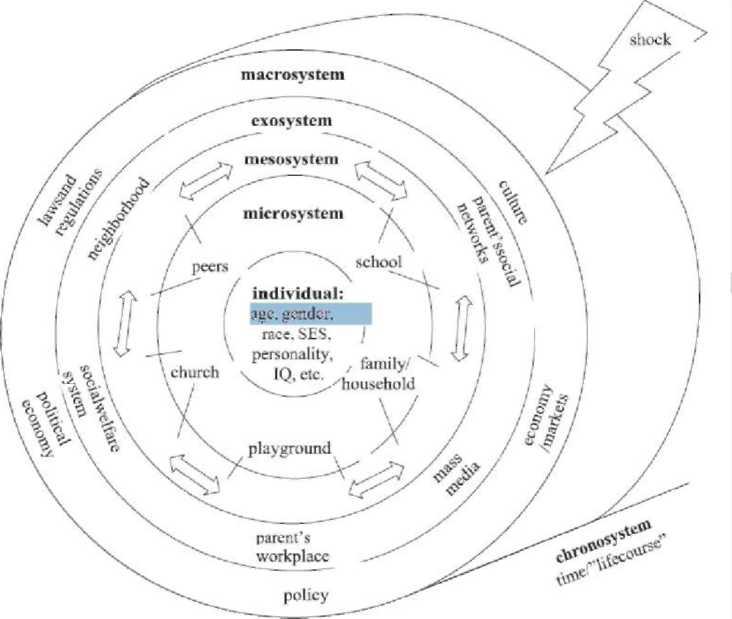

Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model (Figure 7.1) is well suited to illustrate some important dimensions of these human developmental processes, as it captures the complexity of human development as an intricate web of interrelated systems and processes. A basic tenet of the bioecological systems’ theories of development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006) is that child and youth development is influenced by many different “contexts,” “settings,” or “ecologies” (for example, family, peers, schools, communities, sociocultural belief systems, policy regimes, and, of course, the economy).

The model includes the following contexts, ecologies or settings, within the life of the individual:

- individual

- microsystem- immediate environment which includes family, school, peers

- mesosystem – relationships between microsystems, can affect what happens within an individual

- exo- and macrosystem: the belief systems, bodies of knowledge, material resources, customs, lifestyles

Figure 7.1 Bioecological Model of Human Development

Note: SES = socioeconomic status.

Remember Luca in the beginning of the chapter? Here is how this model helped Luca’s teacher Mrs. Hughes consider all the factors of the situation.

|

Context or Setting |

Description |

Example regarding Luca at the front of the chapter |

|

Individual |

the person involved |

Luca |

|

Microsystem |

immediate environment |

the impact of his school, family, US peers |

|

Mesosystem |

relationship between micros |

the relationship between the family/school or Luca and the teacher Does the family trust the teacher, the school? |

|

Exosystem |

People involved with whom you may not have any contact |

People who could impact but they may not have contact with (school board for example). Someone who has created a code of conduct for the district. |

|

Macrosystem |

cultural groups: could include language, race, gender, religion, class, etc |

Speakers of other languages, different relationship with teachers in their country of origin |

|

Chronosystem |

role of time, when this happened |

When did this family come to the US? How familiar are they with the US system of education? How old is Luca? |

This model is integrative and interdisciplinary, drawing on and relating concepts and hypotheses from disciplines as diverse as biology, behavioral genetics and neurobiology, psychology, sociology, cultural anthropology, history, and economics-focusing on and highlighting processes and links that shape human development through the life course (Bronfenbrenner, 1995).

Aspects of the Bioecological Model

Processes

Put very simply, children’s development is the result of proximal processes; of participating in increasingly complex reciprocal interactions with people, objects, and symbols in their immediate environments (their microsystem contexts) over extended periods of time (represented by the chronosystem) (Bronfenbrenner, 1994a).

Microsystem

According to Bronfenbrenner’s definition, “a microsystem is a pattern of activities, social roles, and interpersonal relations experienced by the developing person in a given face-to-face setting with particular physical, social, and symbolic features that invite, permit, or inhibit engagement in sustained, progressively more complex interaction with, and activity in, the immediate environment” (Bronfenbrenner, 1994b, p. 39).

Examples of settings within the microsystem are families, neighborhoods, day care centers, schools, playgrounds, and so on within which activities, roles, and interpersonal relations set the stage for proximal processes as crucial mechanisms for human development.

Context and the Interplay of Systems and Settings

In the bioecological model, contextual effects are manifested in a complex interplay of the micro-, meso-, exo-, and macrosystems. The ways these systems interact and influence each other can contribute to an understanding of how shocks to the macrosystem, such as a financial crisis, can disrupt the developmental process as it is transmitted to various settings in a child’s microsystem.

Household socioeconomic status, neighborhood characteristics, and school environments, just to mention a few, will determine the quality, frequency, and intensity of proximal processes. There is a significant body of literature that looks at how household poverty and hardship affect child development (see, for example, Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997). Neighborhood and community contexts and their influence on children have also been studied extensively (see, for example, Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, & Aber, 1997).

For instance, although family socioeconomic status is correlated with well-being and human development, it is not clear if socioeconomic status causes variations in health and well-being or if personal characteristics and dispositions of individuals influence both their socioeconomic status and their future socioemotional well-being and behavior (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010, p. 687; Mayer, 1997).

In addition, studies have started to unravel the pathways through which poverty affects child and youth development, ranging from the availability of quality prenatal and perinatal care, exposure to environmental toxins such as lead, less cognitive stimulation at home, harsh and inconsistent parenting, to lower teacher quality (McLoyd, 1998).

Furthermore, various studies have compared the implications of temporary versus chronic deprivation and how the impact differs according to the life stage of the developing person (Elder, 1999; McLoyd, 1998; McLoyd et al., 2009). In other words, a temporary drop in socioeconomic status during a crisis may have markedly different long-term implications depending on the age of the child.

Mesosystem

A mesosystem, according to Bronfenbrenner, “comprises the linkages and processes taking place between two or more settings containing the developing person” (1994b, p. 40), such as the relations between home and school. He notes that “it is formed or extended whenever the developing person moves into a new setting” (1979, p. 25).

The main distinction between the meso- and the microsystem is that in the microsystem activities, social roles, and interpersonal relations are confined to one setting, whereas the mesosystem incorporates the interactions across the boundaries of at least two settings (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 209).

Settings in the mesosystem can enhance (or diminish) people’s developmental potential when:

(1) a transition is made together with a group of others that they have engaged with in previous settings (versus alone) (for example, transition with a group of peers from kindergarten to first grade)

(2) when roles and activities between two settings are compatible (or incompatible) and encourage (or discourage) trust, positive orientation, and consensus on goals, as well as a balance of power in favor of the developing person

(3) when the number of structurally different settings is increased (or decreased) and others are more (or less) mature or experienced

(4) when cultural or subcultural contexts differ from each other

(Bronfenbrenner, 1979, pp. 209-223).

Exosystem

An exosystem refers to “the linkages and processes taking place between two or more settings, at least one of which does not contain the developing person, but in which events occur that indirectly influence processes within the immediate setting in which the developing person lives” (Bronfenbrenner, 1994b, p. 40).

An example of such an exosystem setting would be the parent’s workplace, in which the child does not interact directly, but which could indirectly, through parental stress, job loss, or the like, influence family dynamics and thus the developing child. Consequently, a causal sequence of at least two steps is required to qualify as an exosystem.

The first step is to establish a connection between events in the external setting, or exosystem, which does not include the developing person, to processes in the microsystem, which does include the person, and, second, to link these processes to developmental changes in the developing person (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Important to note in this context is the ability of the child to influence parents just as much as parents influence the child, and this influence can reach far beyond the family into settings of the child’s exosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

Research to date has focused on three prominent exosystems that are particularly likely to influence the developmental processes of children and youth through their influence on the family, school, and peers:

- parents’ workplaces,

- family social networks,

- neighborhood-community contexts (Bronfenbrenner, 1994b).

Macrosystem

The macrosystem captures “the overarching pattern of micro-, meso-, and exosystems characteristic of a given culture or subculture, with particular reference to the belief systems, bodies of knowledge, material resources, customs, lifestyles, opportunity structures, hazards, and lifecourse options that are embedded in each of these broader systems” (Bronfenbrenner, 1994b, p. 40). These include the laws and regulations, political economy, economic markets, and public policies of the societies within which the developing person is embedded.

The macrosystem can be interpreted as “space” that Lefebvre (1991) defined as an “unavoidably social product created from a mix of legal, political, economic, and social practices and structures” (p. 190). Individuals draw on these cultural tools that their environment puts at their disposal, or that they choose to make sense of challenges and imagine effective solutions. They also find strategies for action by observing the behaviors of those around them and the consequences of their actions.

The bioecological model is flexible enough to accommodate cross-national variations in the weight given to various aspects of human development influenced by the local culture (for instance, the greater emphasis on self-esteem, self-actualization, and individualization characteristic of the American upper-middle class; see Markus, 2004). It also takes into consideration meso- and macro level conditions for collective human development, including shared myths and narratives that buttress the individual sense of self and capabilities (see, for example, Hall & Lamont, 2009).

The bioecological model is capable of capturing “experiences.” Proximal processes and other interactions are “experienced by the developing person,” which is meant to indicate, “that the scientifically relevant features of any environment include not only its objective properties but also the way in which these properties are perceived by the persons in that environment” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 22). Experiences in this sense are individual (and collective) constructs of the “objective,” which determines an individual’s (and a group’s) capacity for making meaning and for self-representation (Hall & Lamont, 2009). Experiences, while in part determined by the individual’s personality, are embedded in local culture and customs; thus, understanding the cultural frameworks and narratives that shape the relationships and processes within and between settings and systems is crucial to recognizing factors that enhance or weaken the resilience of a developing person.

Educational Implications

The Bioecological Model by Bronfenbrenner looked at patterns of development across time as well as the interactions between the development of the child and the environment.

The implications of the model include the social and political policies and practices affecting children, families, and parenting. The Bioecological Model as depicted in Figure 7.1 serves as a visual organizer to both summarize and unpack key concepts and themes as they relate to individual development, teaching and learning, and educational practices.

As teachers and educators strive to become evidence-based practitioners, the goal of learning this model is to understand the theoretical and research foundations that inform the work in supporting students’ well-being, teaching and learning and identify and use other factors/resources such as parents, family, peers, to provide positive influence on students’ learning and development.

In that regard, Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model encourages much consideration of what constitutes supportive interactions in fostering development. It goes beyond identifying what might influence development, and, more importantly, assists in considering how and why it influences development. Furthermore, Bronfenbrenner’s theory also assists in considering how an interaction might be added or taken away or improved to foster development and, especially, how a face-to-face interaction between a developing individual and an agent within his or her environment might be changed. Although Bronfenbrenner’s multi-system model has value in identifying the resources that influence development, it is likely of most value in assisting consideration of how the resource might be used. Inherent within this idea is the emphasis Bronfenbrenner places on proximal processes, those interactions nearest to the individual have the greatest influence on the development of the individual.

Criticisms of the Bioecological Model

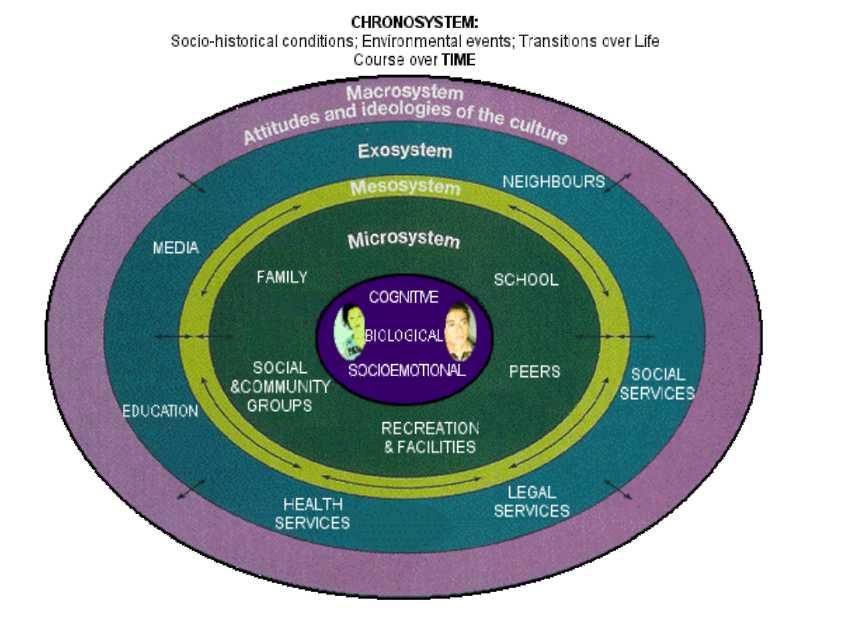

A criticism of Bronfenbrenner has been that the model focuses too much on the biological and cognitive aspects of human development, but not much on the socioemotional aspect of human development. A more comprehensive view of human development with the 3 domains of human development in the center is suggested (Integrated Ecological Systems and Framework, n.d.). This ecological model is called the Integrated Ecological Systems Framework (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 Integrated Ecological Systems Framework

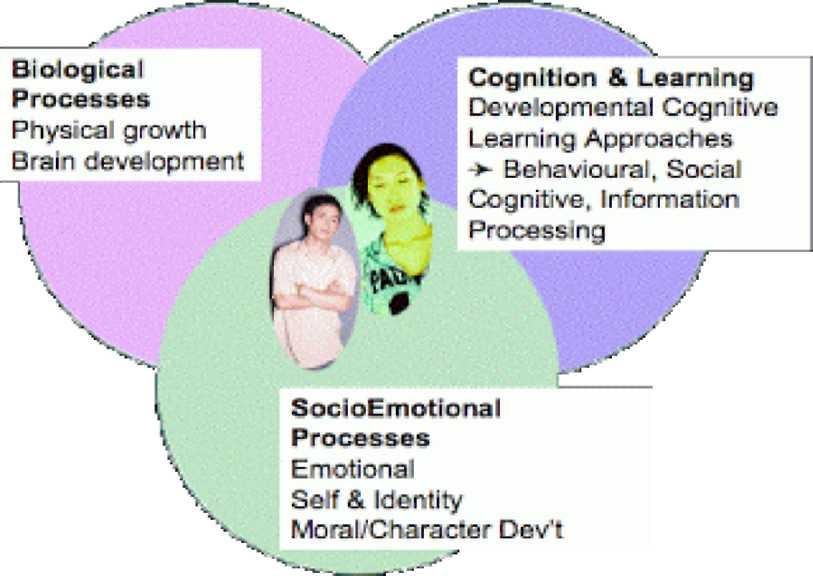

Developmentalists often refer to the three domains as overlapping circles that represent the intricately interwoven relationship between each of the following aspects of an individual’s experience (Figure 7.3).

Biological Processes: the physical changes in an individual’s body.

Cognitive Processes: the changes in an individual’s thinking and intelligence.

Socioemotional Processes: the changes in an individual’s relationship with other people in emotions, in personality and in the role of social contexts in development.

Figure 7.3: Processes of Human Development

Chapter Discussion Questions:

- How do the systems interact to support student success?

- How would you summarize the bioecological model?

- How would you use the specifics of the bioecological model to support your students?

- How is equity related to the bioecological model?

ATTRIBUTIONS

Image 7.1: “Child Development Stages Graphic” by Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Video 7.1: “Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory” by Rachelle Tannenbaum

REFERENCES

Alkire, S. (2002). Dimensions of human development. World Development, 30(2), 181-205. UK: Elsevier Science.

Baumrind, D. (1989). Rearing competent children. In W. Damon (Ed.), Child development today and tomorrow (pp. 349378). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Nature-Nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychological Review, 101(4), 568-86.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1995). Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective. In P. Moen, G. Elder, & K. Lusher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 619-647). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The biological model of human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 793-828). New York, NY: Wiley.

Carter, P. (2007). Keeping it real: School success beyond black and white. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Conger, R., K. Conger, & Martin, M. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 685-704.

Corrales, K., & Utter, S. (2005). Growth failure. In P. Q. Samour & K. King, Handbook of pediatric nutrition (3rd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Damon, W., & Lerner, R. M. (1998). Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development. New York, NY: Wiley.

Duncan, G., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (Eds.). (1997). Consequences of growing up poor. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Elder, G., & Caspi, A. (1988). Economic stress in lives: Developmental perspectives. Journal of Social Issues, 44 (4), 2545.

Florsheim, P., Tolan P. H., & Gorman-Smith, D. (1996). Family processes and risk for externalizing behavior problems among African American and Hispanic boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64 (6), 1222-1230.

Furstenburg, F. F., Cook, T., Eccles, J., Elder, G. H., & Sameroff, A. (1999).

Managing to make it: Urban families in high-risk neighborhoods. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Garcia-Coll, C., Lamberty, G., Jenkins, R., Mc Adoo, H. P., Crnic, P., Wasik, B. H., & Vazquez, H. G. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 18911914.

Gottlieb, G., Wahlsten, D., & Lickliter, R. (1998). The significance of biology for human development: A developmental psychobiological systems view.” In R Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., Vol. 1). New York, NY: Wiley.

Hall, P., & Lamont, M. (Eds.). (2009). Successful societies: How institutions and culture affect health. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Integrated ecological systems and framework. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/humandevelopmentlearning/integrated-framework

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing.

Markus, H. R. (2004). Culture and personality: Brief for an arranged marriage. Journal of Research in Personality, 38, 7583.

Martin, D., McCann, E., & Purcell, M. (2003). Space, scale, governance, and representation: Contemporary geographical perspectives on urban politics and policy. Journal of Urban Affairs, 25(2), 113-121.

McLoyd, V. C. (1990). The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development, 61(2), 311-346.

Pearlin, L., & Kohn, M. (2009). Social class, occupation, and parental values: A cross-national study. In A. Grey (Ed.), Class and personality in society (pp. 161-184). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Rodriguez, M. L., & Walden, N. J. (2010). Socializing relationships. In D. P. Swanson, C. M. Edwards, & M. B. Spencer (Eds.), Adolescence: Development during a global era (pp. 299-340). Burlington, MA: Academic Press.

Thelen, E., & Smith, L. (1998). Dynamic systems theories. In R. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

Warikoo, N. (2010). Balancing act: Youth culture in the global city. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

ADDITIONAL READING

Boemmel, J., & Briscoe, J. (2001). Web Quest project theory fact sheet on Urie Bronfenbrenner. Retrieved from http://ruby.fgcu.edu/courses/twimberley/EnviroPol/EnviroPhilo/FactSheet.pdf

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. Retrieved from

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0114/abstract

Bronfenbrenner, U. (n.d.). Ecological models of human development. Retrieved from

http://www.psy.cmu.edu/~siegler/35bronfebrenner94.pdf

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977.) Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Retrieved from

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.458.7039&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles:

Brendtro, L. K. (2006). The vision of Urie Bronfenbrenner: Adults who are crazy about kids.

Reclaiming Children and Youth, 15(3), 162-166.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513530. Retrieved from http://www2.humboldt.edu/cdblog/CD350-Hansen/wp-

content/uploads/sites/28/2014/08/Bronfenbrenner.pdf

Guhn, M., & Goelman, H. (2011). Bioecological theory, early child development and the validation of the population level early development instrument. Social Indicators Research, 103(2), 193-217.

Lang, S. S. (2005). Renowned bioecologist addresses the future of human development.

Human Ecology, 32(3), 24-24.

Rosa, E. M., & Tudge, J. (2013). Urie Bronfenbrenner’s theory of human development: Its evolution from ecology to bioecology. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 5(4), 243-258.

Stolzer, J. (2005). ADHD in America: A bioecological analysis. Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(1), 65-75, 103.

Taylor, E. (2003). Practice methods for working with children who have biologically based mental disorders: A bioecological model. Families in Society, 84(1), 39-50.

Wertsch, J. V. (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 23, 143-151.

Books at Dalton State College Library:

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Friedman, S. L., & Wachs, T. D. (1999). Measuring environment across the life span: Emerging methods and concepts. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Videos and Tutorials:

History of parenting practices: Child development theories. (2006). Retrieved from Films on Demand database.