10 Bloom’s Taxonomy

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify key elements of Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Explain strategies utilized to implement Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Summarize the criticisms of and educational implications of Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Explain how equity is impacted by Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Identify classroom strategies to support the use of Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Select strategies to support student success utilizing Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Develop a plan to implement the use of Bloom’s Taxonomy

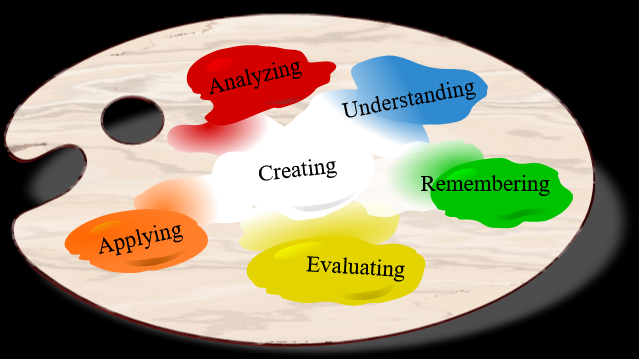

Image 10.1

Scenario:

Ms. Crawley was planning her lessons for the next couple of weeks for her high school history class. Thinking back to her favorite history teacher, she remembered what made it so exciting. They had to role play and debate controversial historical issues like voting rights. Having students play different roles in the debate really got them fired up and engaged. Ms. Crawley wanted to take the learning beyond a simple recall of information. She had to start with some introductory learning of the topic so that the students would be informed as they assumed their roles. She would use a film and read-around to help students understand the issues initially. She would put them in teams so they could create the character who would participate in the debate.

As you learn about Bloom’s Taxonomy, consider the complexity of the learning tasks and where that takes the student. Consider that this is sequential, that Ms. Crawley has to first introduce the information before the students can apply their learning. Consider what students will remember from such an engaging activity!

Check out this video for an introduction:

Video 10.1

INTRODUCTION

Benjamin Samuel Bloom (1913-1999) was born in Lansford, Pennsylvania, and received both a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Pennsylvania State University in 1935. He went on to earn a doctoral degree from the University of Chicago in 1942, where he acted as first a staff member of the Board of Examinations (1940-1943), then a University Examiner (1943-1959), as well as an instructor in the Department of Education.

Bloom’s most recognized and highly regarded initial work spawned from his collaboration with his mentor and fellow examiner Ralph W. Tyler and came to be known as Bloom’s Taxonomy. These ideas are highlighted in his third publication, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook I, The Cognitive Domain. He later wrote a second handbook for the taxonomy in 1964, which focuses on the affective domain. Bloom’s research in early childhood education, published in his 1964 Stability and Change in Human Characteristics sparked widespread interest in children and learning and eventually and directly led to the formation of the Head Start program in America. Aside from his scholarly contributions to the field of education, Benjamin Bloom was an international activist and educational consultant. In 1957, he traveled to India to conduct workshops on evaluation, which led to great changes in the Indian educational system. He helped create the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, the IEA, and organized the International Seminar for Advanced Training in Curriculum Development. He developed the Measurement, Evaluation, and Statistical Analysis (MESA) program at the University of Chicago.

Bloom’s Taxonomy was created in 1956 under the leadership of educational psychologist Dr. Benjamin Bloom in order to promote higher forms of thinking in education, such as analyzing and evaluating concepts, processes, procedures, and principles, rather than just remembering facts (rote learning). It is most often used when designing lesson objectives, learning goals, and instructional activities. Bloom et al. (1956) identified three domains of educational activities or learning:

• Cognitive Domain: mental skills (knowledge)

• Psychomotor Domain: manual or physical skills (skills)

• Affective Domain: growth in feelings or emotional areas (attitude)

Since the work was produced by higher education, the words tend to be a little bigger than what would be normally used. Domains may be thought of as categories. Instructional designers, trainers, and educators often refer to these three categories as KSA (Knowledge [cognitive], Skills [psychomotor], and Attitudes [affective]). This taxonomy of learning behaviors may be thought of as “the goals of the learning process.” That is, after a learning episode, the learner should have acquired a new skill, knowledge, and/or attitude. While Bloom et al. (1956) produced an elaborate compilation for the cognitive and affective domains, they omitted the psychomotor domain. Their explanation for this oversight was that they have little experience in teaching manual skills within the college level. However, there have been at least three psychomotor models created by other researchers. Their compilation divides the three domains into subdivisions, starting from the simplest cognitive process or behavior to the most complex. The divisions outlined are not absolutes and there are other systems or hierarchies that have been devised, such as the Structure of Observed Learning Outcome (SOLO). However, Bloom’s Taxonomy is easily understood and is probably the most widely applied one in use today.

Video 10.2

The Cognitive Domain (Clark, 2015a)

The cognitive domain involves knowledge and the development of intellectual skills (Bloom, 1956). This includes the recall or recognition of specific facts, procedural patterns, and concepts that serve in the development of intellectual abilities and skills. There are six major levels of cognitive processes, starting from the simplest to the most complex:

- Knowledge

- Comprehension

- Application

- Analysis

- Synthesis

- Evaluation

The levels can be thought of as degrees of difficulties. That is, the first ones must normally be mastered before the next one can take place.

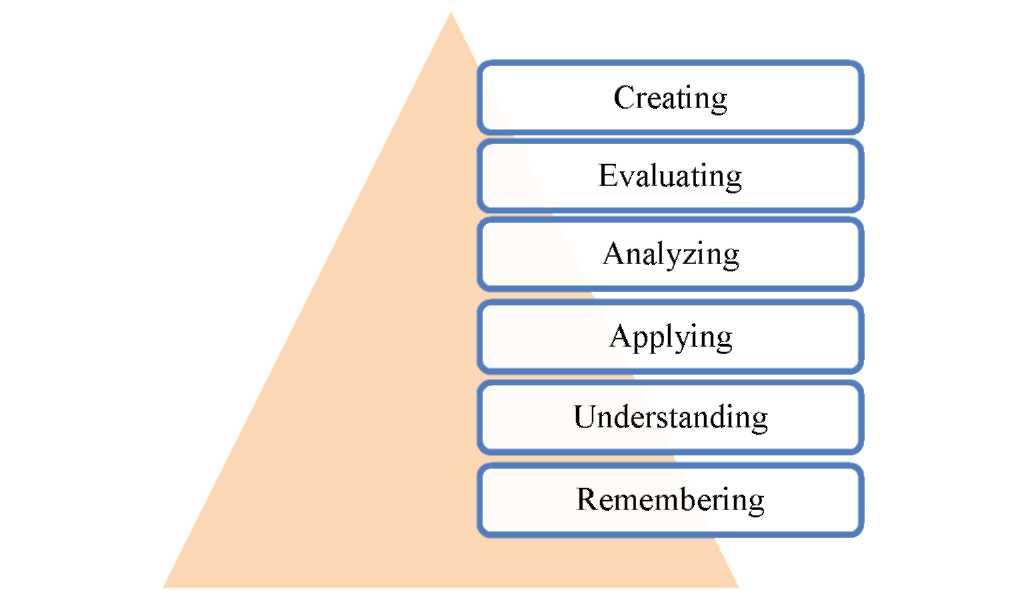

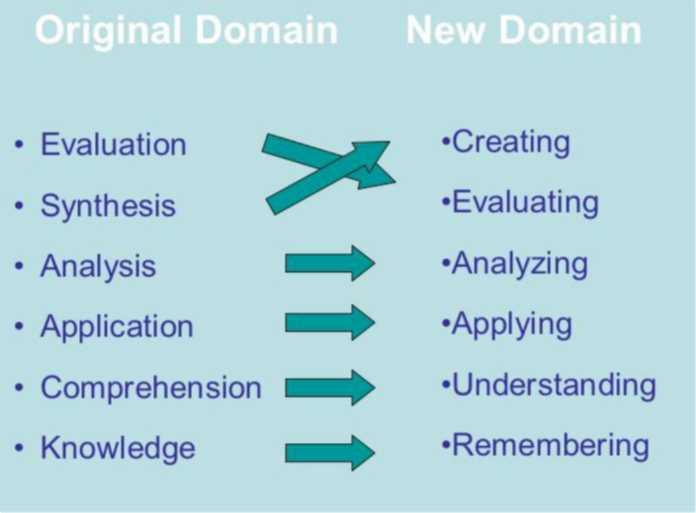

Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy

Lorin Anderson, a former student of Bloom, and David Krathwohl revisited the cognitive domain in the mid-nineties and made some changes, with perhaps the three most prominent ones being:

• Changing the names in the six levels from noun to verb forms;

• Rearranging them as shown in Figure 10.1 and Figure 10.2; and

• Creating a cognitive processes and knowledge dimension matrix (Anderson et al., 2000; Figure 10.5, Figure 10.6, & Figure 10.7).

Figure 10.1 Revised Cognitive Domain

Image 10.2

This new taxonomy reflects a more active form of thinking and is perhaps more accurate. The new version of Bloom’s Taxonomy with examples and keywords is shown in Figure 10.3.

Figure 10.3: Levels of Original and Revised Cognitive Domain with Examples and Key Words

|

Old (Original) Cognitive Domain |

New (Revised) Cognitive Domain |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Levels |

Examples, Key Words (Verbs), and Learning Activities and Technologies |

Levels |

Examples, Key Words (Verbs), and Learning Activities and Technologies |

|

Knowledge: |

Examples: Key Words: |

Remembering: |

Examples: |

|

Comprehension: |

Examples: |

Understanding: |

Examples: |

|

Application: |

Examples: Key Words: |

Applying: |

Examples: |

|

Analysis: |

Examples: Key Words: |

Analyzing: |

Examples: Key Words: |

|

Synthesis: |

Examples: Technologies: |

Evaluating: |

Examples: Key Words: Technologies: |

|

Evaluation: |

Examples: |

Creating: |

Examples: Technologies: |

Image 10.3

Educational Implications

(Clark, 2015d)

Learning or instructional strategies determine the approach for achieving learning objectives and are included in the pre-instructional activities, information presentation, learner activities, testing, and follow-through. The strategies are usually tied to the needs and interests of students to enhance learning and are based on many types of learning styles (Ekwensi, Moranski, & Townsend-Sweet, 2006). Thus the learning objectives point you towards the instructional strategies, while the instructional strategies will point you to the medium that will deliver or assist the delivery of the instruction, such as elearning, self-study, classroom learning and instructional activities, etc.

The Instructional Strategy Selection Chart

(Figure 10.13) shown below is a general guideline for selecting the teaching and learning strategy. It is based on Bloom’s Taxonomy (Learning Domains). The matrix generally runs from the passive learning methods (top rows) to the more active participation methods (bottom rows). Bloom’s Taxonomy (the right three columns) runs from top to bottom, with the lower level behaviors being on top and the higher behaviors being on the bottom. That is, there is a direct correlation in learning:

• Lower levels of performance can normally be taught using the more passive learning methods.

• Higher levels of performance usually require some sort of action or involvement by the learners.

Figure 10.4 Instructional Strategy Selection Chart

|

Instructional Strategy |

Cognitive Domain (Bloom, 1956) |

Psychomotor Domain (Simpson, 1972) |

Affective Domain (Krathwohl, Bloom, & Masia, 1973) |

|

Lecture, reading, audio/visual, demonstration, or guided observations, question and answer period. |

1. Knowledge (Remembering) |

1. Perception 2. Set |

1. Receiving Phenomena |

|

Discussions, multimedia, Socratic didactic method, reflection. Activities such as surveys, role playing, case studies, fishbowls, etc. |

2. Comprehension (Understanding) 3. Application (Applying) |

3. Guided Response 4. Mechanism |

2. Responding to Phenomena |

|

Practice by doing (some direction or coaching is required), to simulated learning settings. |

4. Analysis (Analyzing) |

5. Complex Response |

3. Valuing |

|

Use in real situations. May use several high-level activities. |

5. Synthesis (Evaluating) |

6. Adaptation |

4. Organizing Values into Priorities |

|

Normally developed on own (informal learning) through self-study or learning through mistakes, but mentoring and coaching can speed the process. |

6. Evaluation (Creating) |

7. Origination |

5. Internalizing Values |

The chart above does not cover all possibilities, but most activities should fit in. For example, self-study could fall under reading, audio visual, and/or activities, depending upon the type of learning environment and activities teachers design.

Criticisms of Bloom’s Taxonomy

As Morshead (1965) pointed out on the publication of the second volume, the classification was not a properly constructed taxonomy, as it lacked a systemic rationale of construction. This was subsequently acknowledged in the discussion of the original taxonomy in its 2000 revision (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001), and the taxonomy was reestablished on more systematic lines. It is generally considered that the role the taxonomy played in systematizing a field was more important than any perceived lack of rigor in its construction.

Some critiques of the taxonomy’s cognitive domain admit the existence of six categories of cognitive domain but question the existence of a sequential, hierarchical link (Paul, 1993). Often, educators view the taxonomy as a hierarchy and may mistakenly dismiss the lowest levels as unworthy of teaching (Flannery, 2007; Lawler, 2016). The learning of the lower levels enables the building of skills in the higher levels of the taxonomy, and in some fields, the most important skills are in the lower levels, such as identification of species of plants and animals in the field of natural history (Flannery, 2007; Lawler, 2016). Instructional scaffolding of higher-level skills from lower-level skills is an application of Vygotskian constructivism (Keene, Colvin, & Sissons, 2010; Vygotsky, 1978).

Some consider the three lowest levels as hierarchically ordered, but the three higher levels as parallel (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). Others say that it is sometimes better to move to Application before introducing concepts (Tomei, 2010, p.66). The idea is to create a learning environment where the real world context comes first and the theory second to promote the student’s grasp of the phenomenon, concept or event. This thinking would seem to relate to the method of problem-based learning.

Furthermore, the distinction between the categories can be seen as artificial since any given cognitive task may entail a number of processes. It could even be argued that any attempt to nicely categorize cognitive processes into clean, cut-and-dried classifications undermines the holistic, highly connective and interrelated nature of cognition (Fadul, 2009). This is a criticism that can be directed at taxonomies of mental processes in general.

Chapter Discussion Questions:

- Explain the benefits of Bloom’s Taxonomy to support student success.

- How would you summarize Bloom’s Taxonomy?

- How would you use Bloom’s Taxonomy to support your students?

- How is equity related to Bloom’s Taxonomy?

ATTRIBUTIONS

Image 10.1: “Blooms Taxonomy “, Openclipart is in the Public Domain, CC0

Image 10.2: “The Sound Alternative ” by Learning Policy Institute is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Image 10.3: “Crossroads Elementary School ” by DoDEA is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Video 10.1: “Blooms Taxonomy in the Classroom” by Scott Ragsdale

Video 10.2: “3.2 – How to Write Learning Objectives Using Bloom’s Taxonomy” by Course Design on a Shoestring Budget is licensed under CC BY 4.0

REFERENCES

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P. W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R., … Wittrock, M. C. (2000). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York, NY: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, Handbook I: The cognitive domain. New York, NY: David McKay Co Inc.

Bloom, B.S. (Ed.). Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, Handbook I: The cognitive domain. New York, NY: David McKay Co., Inc.

Clark, D. R. (2015, January 12). Bloom’s taxonomy of learning domains. Retrieved from http: //nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/bloom.html#three_domains

Clark, D. R. (2015a, January 12). Bloom’s Taxonomy: The original cognitive domain. Retrieved from http: //nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/Bloom/original_cognitive_version.html

Clark, D. R. (2015b, January 12). Bloom’s taxonomy: The psychomotor domain. Retrieved from http: //nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/Bloom/psychomotor_domain.html

Clark, D. R. (2015c, January 12). Bloom’s taxonomy: The affective domain. Retrieved from http: //nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/Bloom/affective_domain.html

Clark, D. R. (2015d, January 12). Learning strategies or instructional strategies. Retrieved from http://nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/strategy.html

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2007). E-Learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John

Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Clark, R., & Chopeta, L. (2004). Graphics for learning: Proven guidelines for planning, designing, and evaluating visuals in training materials. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Dave, R. H. (1970). Psychomotor levels. In R. J. Armstrong (Ed.), Developing and writing behavioral objectives (pp. 2021). Tucson, AZ: Educational Innovators Press.

Ekwensi, F., Moranski, J., & Townsend-Sweet, M., (2006). E-Learning concepts and techniques. Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Instructional Technology. Retrieved from

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4ccf/02a87d6044fd181f1efcc0e2f819ef826486.pdf

Fadul, J. A. (2009). Collective learning: Applying distributed cognition for collective intelligence. The International Journal of Learning, 16(4), 211-220.

Flannery, M. C. (2007, November). Observations on biology. The American Biology Teacher, 69(9), 561-564. doi:10.1662/0002-7685(2007)69[561:OOB]2.0.CO;2

Harrow, A. (1972). A taxonomy of psychomotor domain: A guide for developing behavioral objectives. New York, NY: David McKay Co., Inc.

Keene, J., Colvin, J., & Sissons, J. (2010, June). Mapping student information literacy activity against Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive skills. Journal of Information Literacy, 4(1), 6-21. doi: 10.11645/4.1. 189

Krathwohl, D. R., Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1973). Taxonomy of educational objectives, the classification of educational goals. Handbook II: Affective domain. New York, NY: David McKay Co., Inc.

Lawler, S. (2016, February 26). Identification of animals and plants is an essential skill set. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/identification-of-animals-and-plants-is-an-essential-skill-set-55450

Morshead, R. W. (1965). On Taxonomy of educational objectives Handbook II: Affective domain. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 4(1), 164-170. doi :10.1007/bf00373956

Paul, R. (1993). Critical thinking: What every person needs to survive in a rapidly changing world (3rd ed.). Rohnert Park, CA: Sonoma State University Press.

Simpson, E. J. (1972). The classification of educational objectives in the psychomotor domain. Washington, DC: Gryphon House.

Tomei, L. A. (2010). Designing instruction for the traditional, adult, and distance learner: A new engine for technology-based learning. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

ADDITIONAL READING

Credible Articles on the Internet

Armstrong, P. (n.d.). Bloom’s taxonomy. Retrieved from http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

Bloom’s taxonomy of education objectives. (2016). Retrieved from https://teaching.uncc.edu/services-programs/teaching-guides/course-design/blooms-educational-objectives

Bloom’s taxonomy revised: A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.ccri.edu/ctc/pdf/Blooms_Revised_Taxonomy.pdf

Eisner, E. W. (2000). Benjamin Bloom. Prospects: The quarterly review of comparative education, xxx

(3). Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001231/123140eb.pdf

Eisner, E. W. (2002). Benjamin Bloom 1913-99. Retrieved from http://www.ibe.unesco.org/International/Publications/Thinkers/ThinkersPdf/bloome.pdf

Forehand, M. (2005). Bloom’s taxonomy: Original and revised. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Athens, GA: University of Georgia. Retrieved from http://epltt.coe.uga.edu/index.php?title=Bloom%27s_Taxonomy

Hess, K. K., Jones, B. S., Carlock, D., & Walkup, J. R. (2009). Cognitive rigor: Blending the strengths of Bloom’s taxonomy and webb’s depth of knowledge to enhance classroom-level processes. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED517804.pdf

Honan, W. H. (1999). Benjamin Bloom, 86, a leader in the creation of head start. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1999/09/15/us/benjamin-bloom-86-a-leader-in-the-creation-of-head-start.html?pagewanted=1

Huitt, W. (2004). Bloom et al.’s taxonomy of the cognitive domain. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/cognition/bloom.html

Illinois Online Network. (n.d.). Objectives. Retrieved from http://www.ion.uillinois.edu/resources/tutorials/id/developObjectives.asp#top

Overbaugh, R. C., & Schultz, L. (n.d.). Bloom’s taxonomy. Retrieved from http://www.fitnyc.edu/files/pdfs/CET_TL_BloomsTaxonomy.pdf

Shabatura, J. (2013). Using Bloom’s taxonomy to write effective learning objectives. Retrieved from https://tips.uark.edu/using-blooms-taxonomy/

Wilson, L. (2016). Anderson and Krathwohl-Bloom’s taxonomy revised. Retrieved from http://thesecondprinciple.com/teaching-essentials/beyond-bloom-cognitive-taxonomy-revised/

Peer-Reviewed Articles

Athanassiou, N., McNett, J. M., & Harvey, C. (2003). Critical thinking in the management classroom: Bloom’s taxonomy as a learning tool. Journal of Management Education, 27(5), 533-555.

Halawi, L. A., Pires, S., & McCarthy, R. V. (2009). An evaluation of E-learning on the basis of bloom’s taxonomy: An exploratory study. Journal of Education for Business, 84(6), 374-380.

Hogsett, C. (1993). Women’s ways of knowing bloom’s taxonomy. Feminist Teacher, 7 (3), 27.

Kastberg, S. E. (2003). Using bloom’s taxonomy as a framework for classroom assessment. The Mathematics Teacher, 96(6), 402-405.

Seaman, M. (2011). Bloom’s taxonomy: Its evolution, revision, and use in the field of education.

Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue, 13 (1), 29-131A. Page 102

Books from Dalton State College Library

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (Complete ed.). New York, NY: Longman.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals (1st ed.). New York, NY: Longmans & Green.

Videos and Tutorials

The critics: Stories from the inside pages. (2006). Retrieved from Films on Demand database.