3 Social Cognitive Theory

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify key elements of social cognitive theory

- Explain strategies utilized to implement social cognitive theory

- Summarize the criticisms of social cognitive theory and educational implications

- Explain how equity is impacted by social cognitive theory

- Identify classroom strategies to support the use of social cognitive theory

- Select strategies to support student success utilizing social cognitive theory

- Develop a plan to implement the use of social cognitive theory

Image 3.1

SCENARIO:

Yesterday, Ms Mitchell felt exhausted at the end of the school day so today she was going to try something new. In her science class, the students could not seem to follow the neatly printed directions on the white board, nor did the color-coordinated handouts seem to make any difference. She had run around the room trying to respond to the different groups attempting the science project but there was a great deal of confusion. It was one of those days where she questioned her career choice- was she really cut out to be a teacher? After a good night’s sleep and coaching from a colleague, Ms. Mitchell was determined to try a different approach and model every step of the process. After she modeled each section, students seemed to get it quickly. Following some verbal encouragement from Ms. Mitchell, there was soon a happy buzz in the classroom as students engaged with each other in the steps of the science project. Ms. Mitchell was even able to rest her feet, drink her herbal tea and consider what a difference these simple strategies made.

What changes did Ms. Mitchell make? How did modeling the activity change the end result and facilitate their learning? How did her positive remarks reinforce their confidence with the tasks? How did group work also build engagement? As you read through this chapter, consider the power of observation and how learning occurs in a social context with a dynamic and reciprocal interaction of the person, environment, and behavior.

Video 3.1 – Social Cognitive Theory

Introduction

Image 3.2

Albert Bandura (1925-2021) was born in Mundare, Alberta, Canada, the youngest of six children. Both of his parents were immigrants from Eastern Europe. Bandura’s father worked as a track layer for the Trans-Canada railroad while his mother worked in a general store before they were able to buy some land and become farmers. Though times were often hard growing up, Bandura’s parents placed great emphasis on celebrating life and more importantly family. They were also very keen on their children doing well in school. Mundare had only one school at the time so Bandura did all of his schooling in one place.

Bandura attended the University of British Columbia and graduated three years later in 1949 with the Bolocan Award in psychology. Bandura then went to the University of Iowa to complete his graduate work. At the time, the University of Iowa was central to psychological study, especially in the area of social learning theory. By 1952, Bandura completed his Master’s and Ph.D. in clinical psychology. Bandura worked at the Wichita Guidance Center before accepting a position as a faculty member at Stanford University in 1953. Bandura has studied many different topics over the years, including aggression in adolescents (more specifically he was interested in aggression in boys who came from intact middle-class families), children’s abilities to self-regulate and self-reflect, and of course self-efficacy (a person’s perception and beliefs about their ability to produce effects, or influence events that concern their lives).

Bandura is perhaps most famous for his Bobo Doll experiments in the 1960s. At the time there was a popular belief that learning was a result of reinforcement. In the Bobo Doll experiments, Bandura presented children with social models of novel (new) violent behavior or non-violent behavior towards the inflatable rebounding Bobo Doll.

Image 3.3

Children who viewed the violent behavior were in turn violent towards the doll; the control group was rarely violent towards the doll. That became Bandura’s social learning theory in the 1960s. Social learning theory focuses on what people learn from observing and interacting with other people. It is often called a bridge between behaviorist and cognitive learning theories because it encompasses attention, memory, and motivation. Bandura went on to expand motivational and cognitive processes on social learning theory. In 1986, Bandura published his second book Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory, in which he renamed his original social learning theory to be social cognitive theory. Social cognitive theory claims that learning occurs in a social context with a dynamic and reciprocal interaction of the person, environment, and behavior.

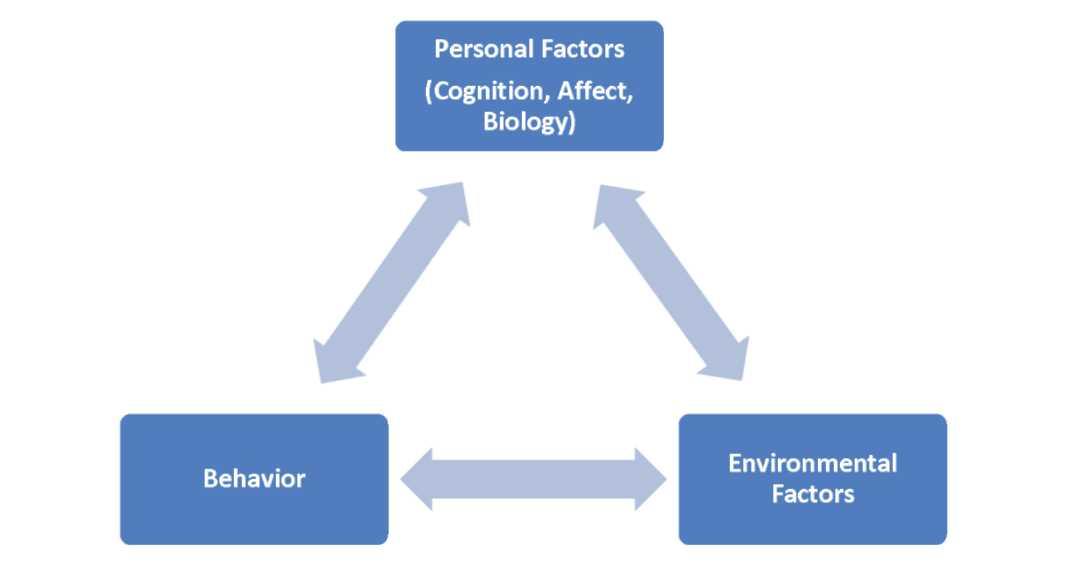

Social Cognitive Theory posits that people are not simply shaped by that environment; they are active participants in their environment. Bandura is highly recognized for his work on social learning theory and social cognitive theory. Social learning is also commonly referred to as observational learning, because it comes about as a result of observing others. Bandura became interested in social aspects of learning at the beginning of his career. Social learning theory emphasizes that behavior, personal factors, and environmental factors are all equal, interlocking determinants of each other (Bandura, 1973, 1977a; Figure 3.1).

Bandura proposed the idea of reciprocal determinism, in which our behavior, personal factors, and environmental factors all influence each other.

Figure 3.1 Reciprocal Determinism

“During their studies of aggression, Bandura and others determined that reciprocal determinism can be seen in everyday observations, and that approximately 75 percent of the time, hostile behavior results in hostile responses, whereas non-hostile acts seldom result in such consequences” (Bandura, 1973).

1. Personal: Whether the individual has high or low self-efficacy toward the behavior (i.e. Get the learner to believe in his or her personal abilities to correctly complete a behavior).

2. Behavioral : The response an individual receives after they perform a behavior (i.e. Provide chances for the learner to experience successful learning as a result of performing the behavior correctly).

3. Environmental: Aspects of the environment or setting that influence the individual’s ability to successfully complete a behavior (i.e. Make environmental conditions conducive for improved self-efficacy by providing appropriate support and materials). (Bandura, 2002)

Overview of Social Cognitive Theory

In 1986, Bandura published his second book Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory,

which expanded and renamed his original theory. He called the new theory Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). Bandura changed the name Social Learning Theory to Social Cognitive Theory to emphasize the major role cognition plays in encoding and performing behaviors. In this book, Bandura (1986) argued that human behavior is caused by personal, behavioral, and environmental influences. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) holds that portions of an individual’s knowledge acquisition can be directly related to observing others within the context of social interactions, experiences, and outside media influences. The theory states that when people observe a model performing a behavior and the consequences of that behavior, they remember the sequence of events and use this information to guide subsequent behaviors. Observing a model can also prompt the viewer to engage in behavior they already learned (Bandura, 1986, 2002).

In other words, people do not learn new behaviors solely by trying them and either succeeding or failing, but rather, the survival of humanity is dependent upon the replication of the actions of others. Depending on whether people are rewarded or punished for their behavior and the outcome of the behavior, the observer may choose to replicate behavior modeled. Media provides models for a vast array of people in many different environmental settings.

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) is a learning theory based on the idea that people learn by observing others. Consider the power of social media today in terms of influence and education. When people want to know something, they turn to Google, Youtube, and Pinterest to see how others do it.

- Learned behaviors can be central to one’s personality. While social psychologists agree that the environment one grows up in contributes to behavior, the individual person (and the way they process/ their cognition) is just as important.

- People learn by observing others, with the environment, behavior, and cognition all as the chief factors in influencing development in a reciprocal triadic relationship (illustrated above in figure 3.1). For example, each behavior witnessed can change a person’s way of thinking (cognition). Similarly, the environment one is raised in may influence later behaviors.

Image 3.3

Human Capability

Evolving over time, human beings are featured with advanced neutral systems, which enable individuals to acquire knowledge and skills by both direct and symbolic terms (Bandura, 2002). Four primary capabilities are addressed as important foundations of social cognitive theory: symbolizing capability, self-regulation capability, self-reflective capability, and vicarious capability.

1. Symbolizing Capability: People are affected not only by direct experience but also indirect events. Instead of merely learning through trial-and-error processes, human beings are able to symbolically perceive events conveyed in messages, construct possible solutions, and evaluate the anticipated outcomes.

Example: People read to learn about history, and can use past events to consider current events.

2. Self-regulation Capability: Individuals can regulate their own intentions and behaviors by themselves. Self-regulation

relies on both negative and positive feedback systems, in which discrepancy reduction and discrepancy production are involved. That is, individuals proactively motivate and guide their actions by setting challenging goals and then making an effort to fulfill them. In doing so, individuals gain skills, resources, and self-efficacy.

Example: People are able to develop goals and work plans to make progress toward long term projects, such as Pursuing a Bachelor’s degree or building a garden shed in their backyard.

3. Self-reflective Capability: Individuals can evaluate their thoughts and actions by themselves, which is identified as another distinct feature of human beings. By verifying the adequacy and soundness of their thoughts through enactive, various, social, or logical manner, individuals can generate new ideas, adjust their thoughts, and take actions accordingly.

Example: People are able to vote on local ballot measures by reading all the voting literature and making educated assessments and decisions.

4. Vicarious Capability: Individuals can adopt skills and knowledge through observation of others’ actions and consequences, which also helps them gain insight into their own activities. From a study in 2002, Bandura concluded that much of the information encountered in our lives derives from mass media rather than a trial-and-error process (Bandura, 2002).

Example: People learn a great deal from current media (Google, Youtube, etc) which has a huge impact on their learning. In today’s world, people google first to understand their next steps.

Core Concepts of Social Cognitive Theory

Modeling/Observational Learning

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) revolves around the process of knowledge acquisition or learning directly correlated to the observation of models. People learn through the observation of modeling, which teaches general rules and strategies for dealing with different situations (Bandura, 1988).

Modeling is the term that best describes and, therefore, is used to characterize the psychological processes that underlie matching behavior (Bandura, 1986):

Learning would be exceedingly laborious, not to mention hazardous, if people had to rely solely on the effects of their own actions to inform them what to do. Fortunately, most human behavior is learned observationally through modeling: from observing others one forms an idea of how new behaviors are performed, and on later occasions this coded information serves as a guide for action. (Bandura, 1977b, p. 22)

In order for modeling /observational learning to occur, four processes exist (Bandura, 1977b, 1986):

- Attention: someone or something gets their attention

- Retention: the information is retained

- Production: practice and application

- Motivation: positive feedback

Outcome Expectancies

To learn a particular behavior, people must understand what the potential outcome is if they repeat that behavior. The observer does not expect the actual rewards or punishments incurred by the model, but anticipates similar outcomes when imitating the behavior (called outcome expectancies), which is why modeling impacts cognition and behavior. These expectancies are heavily influenced by the environment that the observer grows up in; for example, the expected consequences for a DUI in the United States of America are a fine, with possible jail time, whereas the same charge in another country might lead to the infliction of the death penalty. For example, in the case of a student, the instructions the teacher provides help students see what outcome a particular behavior leads to. It is the duty of the teacher to teach a student that when a behavior is successfully learned, the outcomes are meaningful and valuable to the students.

Self-Regulation

Self-regulation and self-efficacy are two elements of Bandura’s theory that rely heavily on cognitive processes. They represent an individual’s ability to control their behavior through internal reward or punishment in the case of self-regulation, and their beliefs in their ability to achieve desired goals as a result of their own actions, in the case of self-efficacy.

Image 3.4

Self-regulation is a general term that includes both self-reinforcement and self-punishment.

Self-reinforcement works primarily through its motivational effects. When an individual sets a standard of performance for themselves, they judge their behavior and determine whether or not it meets the self-determined criteria for reward. Since many activities do not have absolute measures of success, the individual often sets their standards in relative ways. For example, a weight-lifter might keep track of how much total weight they lift in each training session, and then monitor their improvement over time or as each competition arrives. Although competitions offer the potential for external reward, the individual might still set a personal standard for success, such as being satisfied only if they win at least one of the individual lifts. The standards that individuals set for themselves can be learned through modeling. This can create problems when models are highly competent, much more so than the observer is capable of performing (such as learning the standards of a world-class athlete).

Image 3.5

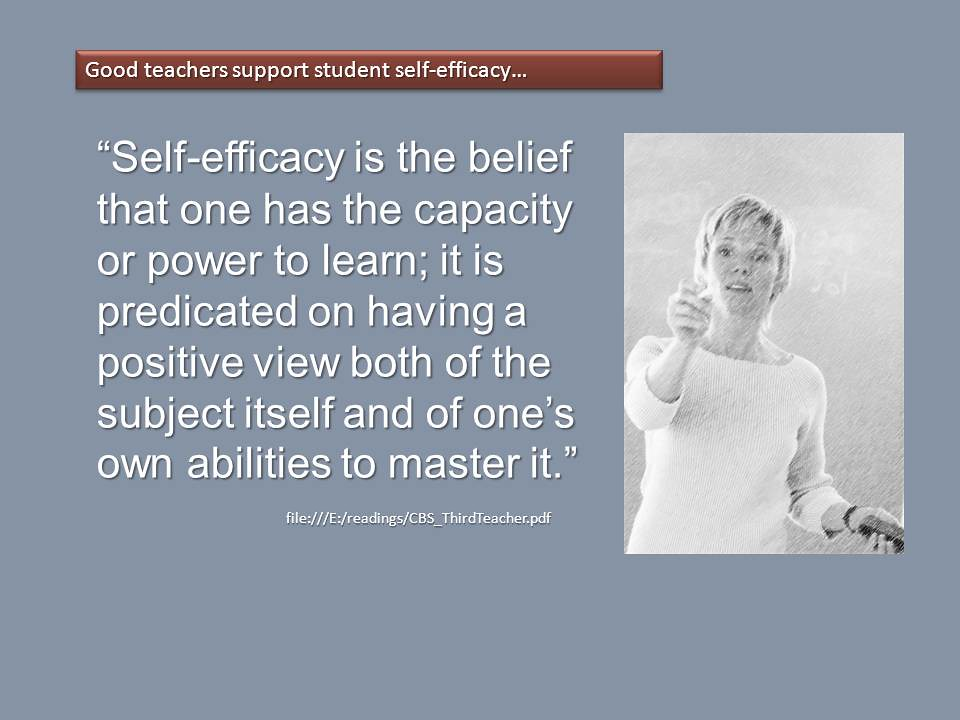

Self-Efficacy

Social Cognitive Theory posits that learning most likely occurs if there is a close identification between the observer and the model, and if the observer also has a good deal of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is the extent to which an individual believes that they can master a particular skill. Self-efficacy beliefs function as an important set of proximal determinants of human motivation, affect, and action-which operate on action through motivational, cognitive, and affective intervening processes (Bandura, 1989).

Self-efficacy can be developed or increased by:

• Mastery experience: which is a process that helps an individual achieve simple tasks that lead to more complex objectives.

• Social modeling: provides an identifiable model that shows the processes that accomplish a behavior.

• Improving physical and emotional states: refers to ensuring a person is rested and relaxed prior to attempting a new behavior. The less relaxed, the less patient, the more likely they won’t attain the goal behavior.

• Verbal persuasion: is providing encouragement for a person to complete a task or achieve a certain behavior. (McAlister, Perry, & Parcel, 2008)

For example, students become more effortful, active, pay attention, highly motivated and better learners when they perceive that they have mastered a particular task (Bandura, 1993). It is the duty of the teacher to allow students to develop and perceive their efficacy by providing feedback to understand their level of proficiency. Teachers should ensure that the students have the knowledge and strategies they need to complete the tasks. Self-efficacy development is an exploring human agency and human capability process.Young children may not have fully developed a sense of what they can and cannot do. So, adult guidance can support young children in developing self-efficacy. For example, they can climb to high places, wander into rivers or deep pools, and wield sharp knives before they develop the necessary skills for managing such situations safely.

The influence of Social Interaction

Social interaction becomes highly influential as students begin their schooling. Not only does the child learn a great deal from the family, but as they grow, peers become increasingly important. As the child’s world expands, peers bring with them a broadening of self-efficacy experiences. This can have both positive and negative consequences. Peers who are most experienced and competent can become important models of behavior. For many children, unfortunately, the academic environment of school is a challenge. Children quickly learn to rank themselves (grades help, both good and bad), and children who do poorly can lose the sense of self-efficacy that is necessary for continued effort at school. According to Bandura, it is important that educational practices focus not only on the content they provide, but also on what they do to children’s beliefs about their abilities (Bandura, 1986, 1997).

Adolescence

Image 3.6

As children continue through adolescence toward adulthood, they need to assume responsibility for themselves in all aspects of life. They must master many new skills, and a sense of confidence in working toward the future is dependent on a developing sense of self-efficacy supported by past experiences of mastery. In adulthood, a healthy and realistic sense of self-efficacy provides the motivation necessary to pursue success in one’s life.

In summary, as we learn more about our world and how it works, we also learn that we can have a significant impact on it. Most importantly, we can have a direct effect on our immediate personal environment, especially with regard to personal relationships, behaviors, and goals. What motivates us to try influencing our environment is specific ways in which we believe, indeed, we can make a difference in a direction we want in life. Thus, research has focused largely on what people think about their efficacy, rather than on their actual ability to achieve their goals (Bandura, 1997).

Impact of Social Cognitive Theory

Bandura is still influencing the world with expansions of Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). SCT has been applied to many areas of human functioning such as career choice and organizational behavior as well as in understanding classroom motivation, learning, and achievement (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 1994). Bandura (2001) brought SCT to mass communication in his journal article that stated the theory could be used to analyze how “symbolic communication influences human thought, affect and action” (p. 3). The theory shows how new behavior diffuses through society by psychosocial factors governing acquisition and adoption of the behavior. Bandura’s (2011) book chapter “The Social and Policy Impact of Social Cognitive Theory” to extend SCT’s application in health promotion and urgent global issues, which provides insight into addressing global problems through a macro social lens, aiming at improving equality of individuals’ lives under the umbrellas of SCT. This work focuses on how SCT impacts areas of both health and population effects in relation to climate change. He proposes that these problems could be solved through television serial dramas that show models similar to viewers performing the desired behavior.

Bandura (2011) states population growth is a global crisis because of its correlation with depletion and degradation of our planet’s resources. Bandura argues that SCT should be used to get people to use birth control, reduce gender inequality through education, and to model environmental conservation to improve the state of the planet. Green and Peil (2009) reported he has tried to use cognitive theory to solve a number of global problems such as environmental conservation, poverty, soaring population growth, etc.

Criticism of Social Cognitive Theory

- The social cognitive theory is that it is not a unified theory. This means that the different aspects of the theory may not be connected. For example, researchers currently cannot find a connection between observational learning and self-efficacy within the social-cognitive perspective.

- The theory is so broad that not all of its component parts are fully understood and integrated into a single explanation of learning.

The findings associated with this theory are still, for the most part, preliminary. - The theory is limited in that not all social learning can be directly observed. Because of this, it can be difficult to quantify the effect that social cognition has on development.

- Finally, this theory tends to ignore maturation throughout the lifespan. Because of this, the understanding of how a child learns through observation and how an adult learns through observation are not differentiated, and factors of development are not included.

Image 3.7

Educational Implications of Social Cognitive Theory

An important assumption of Social Cognitive Theory is that personal determinants, such as self-reflection and self-regulation, do not have to reside unconsciously within individuals. People can consciously change and develop their cognitive functioning. This is important to the proposition that self-efficacy too can be changed, or enhanced. From this perspective, people are capable of influencing their own motivation and performance according to the model of triadic reciprocality in which personal determinants (such as self-efficacy), environmental conditions (such as treatment conditions), and action (such as practice) are mutually interactive influences. Improving performance, therefore, depends on changing some of these influences.

Relevancy to the classroom:

In teaching and learning, the challenge upfront is to:

- Get the learner to believe in his or her personal capabilities to successfully perform a designated task.

- Provide environmental conditions, such as instructional strategies and appropriate technology, that improve the strategies and self-efficacy of the learner.

- Provide opportunities for the learner to experience successful learning as a result of appropriate action (Self-efficacy Theory, n.d.).

Image 3.8

Implications in classroom teaching and learning practices:

1. Students learn a great deal simply by observing others;

2. Describing the consequences of behavior increases appropriate behaviors, decreasing inappropriate ones; this includes discussing the rewards of various positive behaviors in the classroom;

3. Modeling provides an alternative to teaching new behaviors. To promote effective modeling, teachers must ensure the four essential conditions exist: attention, retention, production, and motivation (reinforcement and punishment);

4. Instead of using shaping, an operant conditioning strategy, teachers will find modeling is a faster and more efficient means of teaching new knowledge, skills, and dispositions;

5. Teachers must model appropriate behaviors and they do not model inappropriate behaviors;

6. Teachers should expose students to a variety of models including peers and other adult models; this is important to break down stereotypes;

7. Modeling also includes modeling of interest, thinking process, attitudes, instructional materials, media (TV and advertisement), academic work achievement and progress, encouragement, emotions, etc. in the physical, mental and emotional aspects of development.

8. Students must believe that they are capable of accomplishing a task; it is important for students to develop a sense of self-efficacy. Teachers can promote such self-efficacy by having students receive confidence-building messages, watch others be successful, and experience success on themselves;

9. Teachers should help students set realistic expectations ensuring that expectations are realistically challenging. Sometimes a task is beyond a student’s ability;

10. Self-regulation techniques provide an effective method for improving student behaviors.

Chapter Discussion Questions:

- Explain the benefits of social cognitive theory to support students?

- How would you summarize social cognitive theory?

- How would you use social cognitive theory to support your students?

- How is equity impacted by the use of social cognitive theory?

ATTRIBUTIONS

Image 3.1 “The Clear and Direct Attach on America’s Children” by Learning Policy Institute

Image 3.2 “Albert Bandura Psychologist” by Wikipedia Commons

Image 3.3 “Neural networks, Explain That Stuff” by Chris Woodford

Image 3.4 “Children Learn how to make” by U.S. Department of Agriculture

Image 3.5 “Educational Postcard: “Definition of Self-efficacy”Children Learn how to make” by Ken Whytock

Image 3.6 Young Teenagers Playing Guitar Band of Youth, Wikimedia Commons

Image 3.7 “A teenager engrossed in his smartphone.” by Pabak Sarkar

Image 3.8 “Participants of the first Air Force resiliency teen” by Defense Visual Information Distribution Service

FILMS

“Social Cognitive Theory” by youtube is in the Public Domain

“Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory” by youtube is in the Public Domain

REFERENCES

Ahmed, A. (2009, July). Effect of breastfeeding educational program based of Bandura social cognitive theory on breastfeeding outcomes among mothers of preterm infants. Poster presented at the ILCA Conference, Orlando, FL.

Aubrey, J. S. (2004). Sex and punishment: An examination of sexual consequences and the sexual double standard in teen programming. Sex Roles, 50(7-8), 505-514. Page 29

Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1977a). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191215. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1977b). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought & action: A social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1988). Organizational application of social cognitive theory. Australian Journal of Management, 13(2), 275302. doi :10.1177/031289628801300210

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44 (9), 1175-1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist,28(2),

117-148. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3

Bandura, A. (1994). Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. Preventing AIDS, 25-59.

Bandura, A. (1995). Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3(3), 265-299. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03

Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In J. Bryant & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 94-124). New York, NY: Routledge.

Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31 (2), 143-164.

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1, 164-180.

Bandura, A. (2011). The social and policy impact of social cognitive theory. In M. Mark, S. Donaldson, & B. Campbell (Eds.), Social psychology and evaluation (pp. 33-70). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1963). Social learning and personality development. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1963). A comparative test of the status envy, social power, and secondary reinforcement the ries of identificatory learning. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 527-534.

Evans, R. I., & Bandura, A. (1989). Albert Bandura, the man and his ideas: A dialogue. New York, NY: Praeger.

Green, M., & Peil, J. A. (2009). Theories of human development: A comparative approach (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Inc.

Hardin, M., & Greer, J. D. (2009). The influence of gender-role socialization, media use and sports participation on perceptions of gender-appropriate sports. Journal of Sport Behavior, 32 (2), 207-226.

Lent, R., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994, August). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45 (1), 79-122.

Martino, S. C., Collins, R. L., Kanouse, D. E., Elliott, M., & Berry, S. H. (2005). Social cognitive processes mediating the relationship between exposure to television’s sexual content and adolescents’ sexual behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89 (6), 914.

Mastro, D. E, & Stern, S. R. (2003). Representations of race in television commercials: A content analysis of prime-time advertising. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 47 (4), 638-647.

McAlister, A. L., Perry, C. L., & Parcel, G. S. (2008). How individuals, environments, and health behaviors interact: Social cognitive theory. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (4th ed., pp. 169-188). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Miller, K. (2005). Communication theories: Perspectives, processes, and contexts (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Nabi, R. L., & Clark, S. (2008). Exploring the limits of social cognitive theory: Why negatively reinforced behaviors on TV may be modeled anyway. Journal of Communication, 58 (3), 407-427.

Ormrod, J. (2008). Human learning (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Pajares, F., Prestin, A., Chen, J., & Nabi, R. L. (2009). Social cognitive theory and media effects. In R. L. Nabi, & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), The sage handbook of media processes and effects (pp. 283-297). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Raman, P., Harwood, J., Weis, D., Anderson, J. L., & Miller, G. (2008). Portrayals of older adults in US and Indian magazine advertisements: A cross-cultural comparison. The Howard Journal of Communications,19(3), 221-240.

Santrock, J. W. (2008). A topical approach to lifespan development. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Inc. Self-efficacy theory. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://edutechwiki.unige.ch/en/Self-efficacy_theory

ADDITIONAL READING

Credible Articles on the Internet

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. The American Psychologist, 44, 1175-1184. Retrieved from http://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/Bandura1989AP.pdf

Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of child development (pp. 1-60). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Retrieved from http://www.des.emory.edu/mfp/Bandura1989ACD.pdf

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (pp. 71-81). New York, NY: Academic Press. Retrieved from http://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/Bandura1994EHB.pdf

Bandura, A. (1999). A social cognitive theory of personality. In L. Pervin, & O. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality, (2nd ed., pp. 154-196). New York, NY: Guilford Publications. Retrieved from https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/Bandura1999HP.pdf

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Retrieved from http://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/BanduraPubs/Bandura1991OBHDP.pdf

Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Journal of Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51, 269-290. Retrieved from http://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/Bandura2002AP.pdf

Beck, H. P. (2001). Social learning theory. Retrieved from http://www1.appstate.edu/~beckhp/aggsociallearning.htm

Boeree, C. (2009). Personality theories: Albert Bandura. Retrieved from http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/bandura.html

Green, C. (1999). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. Retrieved from

http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Bandura/bobo.htm

McLeod, S. (2016). Bandura: Social learning theory. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/bandura.html

Moore, A. (1999). Albert Bandura. Retrieved from http://www.muskingum.edu/~psych/psycweb/history/bandura.htm

Pajares, F. (2002). Overview of social cognitive theory and of self-efficacy. Retrieved from https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Pajares/eff.htm

Social learning theory. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/a/nau.edu/educationallearningtheories/home/social-learning-thoery

Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles

Grusec, J. E. (1992). Social learning theory and developmental psychology: The legacies of Robert Sears and Albert Bandura. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 776-786.

Ponton, M. K., & Rhea, N. E. (2006). Autonomous learning from social cognitive perspective. New Horizons in Adult Education & Human Resource Development, 20(2), 38-49.

Books in Dalton State College Library

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1959). Adolescent aggression: A study of the influence of child-training practices and family interrelationships . New York, NY: Ronald Press Co.

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1963). Social learning and personality development. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Videos and Tutorials

Bandura’s Bobo doll experiment. (2012). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dmBqwWlJg8U

Films Media Group. (2003). Bandura’s social cognitive theory: An introduction. Retrieved from Films on Demand database.