5 Week 5 – Voice

Leigh Hancock and Michelle Bonczek Evory

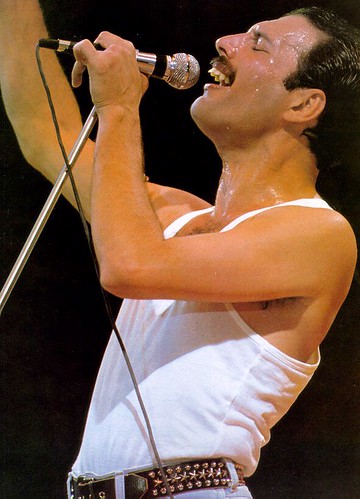

“Freddie Mercury” by kentarotakizawa is licensed under CC BY 2.0

When we talk of “voice” in a poem, we are identifying the characteristics that make up the way that we “hear” the speaker of the poem. The voice of a poem is responsible for creating trust between the reader and the speaker, in seducing the reader to lose him or herself in the experience. Voice helps a reader be enraptured by the poem.

Poet Billy Collins explains how the voice of a poem took on a bigger role once Modern poetry began to experiment with free verse:

Once Walt Whitman demonstrated that poetry in English could get along without standard meter and end-rhyme, poetry began to lose that familiar gait and musical jauntiness that listeners and readers had come to identify with it. But poetry also lost something more: a trust system that had bound poet and reader together through the reliable recurrence of similar sounds and a steady dependable beat. Whatever emotional or intellectual demands a poem placed on the reader, at least the reader could put trust in the poet’s implicit promise to keep up a tempo and maintain a sound pattern. It is the same promise that is made to the listeners of popular songs. What has come to replace that system of trust, if anything? However vague a substitute, the answer is probably tone of voice. As a reader, I come to trust or distrust the authority of the poem after reading just a few lines. Do I hear a voice that’s making reasonable claims for itself—usually a first-person voice speaking fallibly but honestly—or does the poem begin with a grandiose pronouncement, a riddle, or an intimate confession foisted on me by a stranger? Tone may be the most elusive aspect of written language, but our ears instantly recognize words that sound authentic and words that ring false. The character of the speaker’s voice played an indescribable but essential role in the making of those two piles I mentioned, one much taller than the other.

It is interesting that Collins refers negatively to the “voice of a stranger” as aren’t all speakers of poems strangers to a reader? We do not know the poet, so how can we possibly know the speaker? Yet here, Collins suggests that there is something in us that does know something of the speaker, some credibility that “sounds authentic” rather than “ringing false,” and this has more to do with tone of voice than subject matter. After all, who believes someone who doesn’t sound trustworthy? It is like watching a play with bad acting—you can’t lose yourself in the story or character, you cannot transport, you cannot release yourself to get “caught in its spell.” We have trouble trusting our senses and giving our time to the speaker without suspicion, which acts as a barrier between the reader and the experience. It is similar to what poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge called a “suspension of disbelief,” in a sense: We need to be willing to be wrapped up in a poem’s experience and if we’re untrusting than we’re not willing. Tone of voice develops from the many moves a poem makes and can be considered, in another way, the stance the speaker takes, the relationship between the subject matter and the speaker.

What Makes Voice

Voice depends on a variety of elements that make up the poems:

Subject Matter: Sharon Olds writes frequently about her father; William Heyen about the Holocaust; Mary Oliver about nature and animals. These subjects are not all that these writers choose to write about, but they do have a heavy, repetitive presence in their collections. To some extent, we associate the “voice” of these authors with their subjects.

Tone and Mood: Some poets (Dylan Thomas, for instance, or Matthew Arnold) are known for the serious voice of their poems. Other poets, like Billy Collins or William Carlos Williams, have a more playful, quirky approach or voice. Ezra Pound’s voice is that of a highly educated, cerebral man, while Lucinda Clifton writes with the rhythm and sass of a strong-minded African American woman. And many poets employ multiple and diverse voices depending on their subject matter and intent.

Diction: Perhaps the most influential element that creates voice and tone is diction, a term we use for “word choice” or the vocabulary used in a piece of writing. There is a range of diction—formal, informal, conversational, slang—and the words we choose reveal the emotional coloring of the speaker and the stance of the speaker in relation to the subject. There are no two words that mean the exact same thing—regardless of what a thesaurus tells you; synonyms are simply related, not exact variants. Diction can also reveal a speaker’s range of knowledge, education, culture, and regional influence. Dooes the poet say sneakers or tennis shoes? Soda or pop? Car or automobile?

Syntax and Grammar: Working hand in hand with diction is syntax, which refers to the order in which words are arranged. Syntax is how the poet delivers his or her thoughts. What the poet chooses to say creates character and voice in more than one way. Some of what’s related to syntax and grammar are sentence length, fragments, and active or passive voice.

Types of Images: Like subject matter, writers tend to favor certain images or image types. Read through Michael Burkard’s collected poems and you’ll find frequent uses of trains, rain, and shadows. Some poets’ bodies of work are filled with birds, or flowers, or astronomical metaphors, or images of the body.

Form: By simply looking at a poem on the page we may be able to identify a poet’s voice. Emily Dickinson’s short poems with stanzas and lines of equal length. Norman Dubie’s willingness to mix different stanzas and line lengths—a couplet followed by a sextet (six-line stanza), followed by a single line that stands on its own. e.e. cummings’s abandonment of punctuation and capitalization. All o f these affect the voice of the poem.

Persona

“A Poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in existence,” wrote John Keats, “because he has no Identity—he is continually in for—and filling some other Body.” In a letter to his brother, Keats famously wrote of the concept of “negative capability,” which he described as “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.” A type of cognitive dissonance, in which one can peacefully hold two opposing thoughts in the mind at once, Keats’ negative capability is what allows us as poets to imaginatively and empathetically muse upon the subject of our poems, or to enter the world of another, to speak from an imagined experience as if it were our own. In a persona poem, the poet adopts the perspective of a character or speaker in a specific situation. The poet steps outside his or her own body and into the body of this imagined speaker.

Adopting a persona widens a poet’s range of subject matter. It allows us to explore different subjects and points of view. Rather than only writing from our experience, we can invent a new character or speak from a person in history or in literature. In his book-length poem Shannon, Campbell McGrath speaks from the perspective of the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s youngest member Shannon when he goes missing in the prairie for over two weeks. Based on history, McGrath fills in the events and details no one could ever know. Speaking as Shannon, he writes:

The rest of the day the country shimmers

In a haze, these buffalo

Have no fear of me

Their eyes loll & moon in the grass

& I must shout to start them from my path

& hurl a stick at one brute

Oblivious as if I were invisible

Or he aware of my absolute helplessness.

William Heyen, also inspired by history, in his book Crazyhorse in Stillness, speaks from many personas. In the following, he depicts the plight of the buffalo by writing in the voice of an anonymous man hired on the prairie around the time of the Battle of Little Big Horn:

Job

I liked picking up the skulls best.

I could fling a calf’s by one horn

maybe twenty feet into the wagon.

It didn’t matter if it busted—

in fact, the smaller pieces the better.

But a bull’s skull took two of us

to twist it off its stem and lift it.

You each grabbed a horn,

or did it the smart way with a pole

through the jaw and an eyesocket.

All in all, it was good work,

but ran out, but you had the feeling

of clearing something up, a job

no one would need to do again.

Copyright ©William Heyen “Job” is licensed CC-BY-NC-SA.

Traci Brimhall’s poems in the book Our Lady of Ruins speak from the personas of multiple women ravaged by war:

Our Bodies Break Light

We crawl through the tall grass and idle light,

our chests against the earth so we can hear the river

underground. Our backs carry rotting wood and books

that hold no stories of damnation or miracles.

One day as we listen for water, we find a beekeeper—

one eye pearled by a cataract, the other cut out by his own hand

so he might know both types of blindness. When we stand

in front of him, he says we are prisms breaking light into color—

our right shoulders red, our left hips a wavering indigo.

His apiaries are empty except for dead queens, and he sits

on his quiet boxes humming as he licks honey from the bodies

of drones. He tells me he smelled my southern skin for miles,

says the graveyard is full of dead prophets. To you, he presents

his arms, tattooed with songs slave catchers whistle

as they unleash the dogs. He lets you see the burns on his chest

from the time he set fire to boats and pushed them out to sea.

You ask why no one believes in madness anymore,

and he tells you stars need a darkness to see themselves by.

When you ask about resurrection, he says, How can you doubt?

and shows you a deer licking salt from a lynched man’s palm.

“Our Bodies Break Light”, from OUR LADY OF THE RUINS: POEMS by Traci Brimhall. Copyright © 2012 by Traci Brimhall. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Point of View

Point of view also affects how we hear and receive the voice of a poem:

First Person ● I/We ● I went to the store to buy milk.

Most poets begin writing in first person, taking their own experiences as subject matter. The first-person point of view is present in memoir, the personal essay, and in autobiography and it allows us to be very close to not only the speaker’s observations, but also with his or her thoughts. This is the point of view used in a persona poem or a dramatic monologue.

Second Person ● You ● You went to the store to buy milk.

When poets use this point of view, they may be addressing a particular person in the poem, or they may be addressing the reader. They may even be talking about the speaker, attempting to make the reader imagine being the “I” which is really the “you.” This perspective can make the reader a character and it can also create a deep sense of connection between the reader and the speaker.

Third Person ● He/She/It ● Her daughter went to the store to buy milk.

Omniscient “Toby fastened his seatbelt and looked out the passenger side window. His mother, worrying about being late for the match, blasted the gas. Toby squeezed his hands into fists. He didn’t want to go. He thought himself better off at the playground. On the swings where he left her, Susan rebraided her hair. By the next day she’d forget what Toby had told her.”

The omniscient speaker is powerful and godlike, not limited by space or time. This speaker can enter the thoughts of all characters, is flexible and can go anywhere, anytime.

Limited Omniscient “Toby fastened his seatbelt and looked out the passenger side window. His mother, worrying about being late for the match, blasted the gas. Toby squeezed his hands into fists. His mother figured that he didn’t want to go. But she didn’t feel comfortable with him and Susan being unsupervised at the playground—especially with how much “in love” he might be thinking he was.”

In this example, we are limited to Toby’s mother’s thoughts. We can observe Toby but we cannot enter his thoughts. As readers we ride alongside with Toby’s mother, struggling as she does, experiencing what she does, discovering things only when she does. We are limited to her interpretations of the world—even if they are incorrect.

Objective “Toby fastened his seatbelt and looked out the passenger side window. His mother blasted the gas. “Now we’re going to be late,” she said. Toby squeezed his hands into fists and rolled his eyes. Through the rear window, on the swings where he left her, he could see Susan rebraiding her hair.”

Here, the most distant of the perspectives, we can observe only what a witness could sense with his nose, ears, mouth, eyes, and skin. Any judgments we make must arise from the text and where the speaker directs our attention.