3.3 How Agencies Plan for the Future

Internships are a unique opportunity to understand how agencies function, starting with how the leaders of those organizations support human service workers and sustain the organization as a whole.

Strategic Plans

Strategic planning is how organizations operationalize their mission, vision, and values (Indeed, 2022). It outlines the steps and processes involved in incorporating their ideals into their day-to-day activities. If the mission statement tells you who an agency is, and the vision statement tells you where the agency is going, the strategic plan is the road map that explains how the agency is going to use their mission statement to achieve their vision statement in the next five to seven years. A review of the mission and vision statements is usually part of the strategic planning process, as is the identification and refining of the agency’s values. The plans are usually lengthy and filled with charts, graphs, and specific ideas for getting from where the agency is to where they want to be in the next five to seven years. At least, that is how it is supposed to work.

In the past, human services organizations have developed their strategic plans at the highest level of the organization, utilizing the skills of senior leadership and the governing bodies, such as the board of directors. Once developed, the plan is usually presented briefly at a staff meeting, placed in a notebook, and then set on the shelf for reference, where it is rarely reviewed until the next strategic planning process five to seven years later. Middle management and direct service staff may or may not be given access to the full plan, and even when all staff have access to that notebook, the plans tend to be written in language more common in the business world than in human services.

While the intent may be to have the plan direct and guide the work of the agency, the complexities of running a human services organization can be overwhelming, leaving little time to review the strategic plan. Situations beyond the control of the planning body can also interfere with the agency’s ability to implement its plan. For example, it is highly unlikely that strategic plans developed prior to 2020 included any planning for how to deliver services safely during a global pandemic.

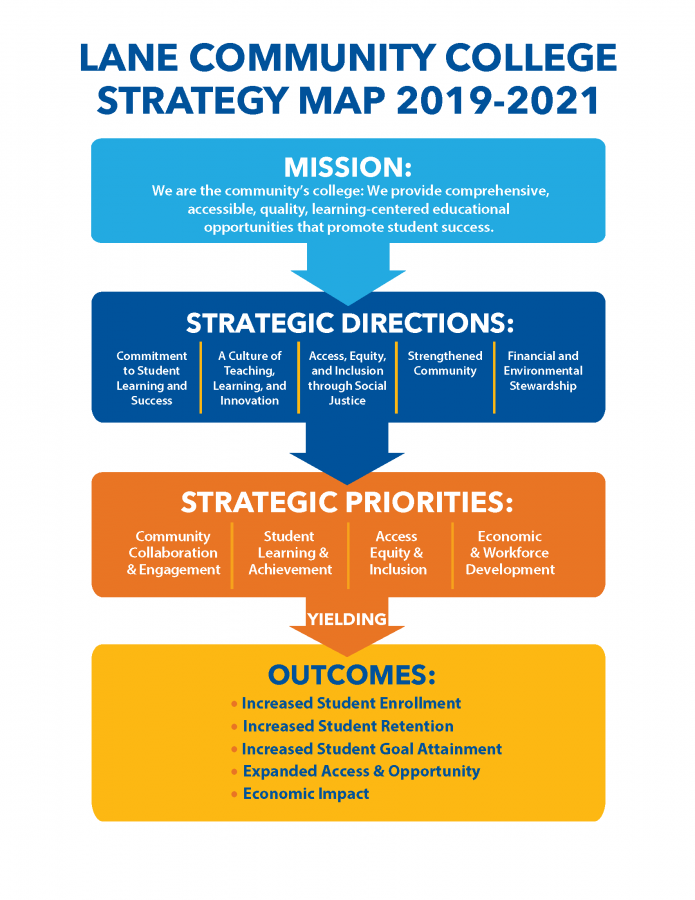

The good news is that things are changing, and strategic plans do not need to be cumbersome or difficult to read or to sit on a shelf gathering dust. Agencies and organizations are beginning to develop infographics to help communicate the basics of their strategic plan and keep the key concepts on everyone’s mind. This increases transparency, communication, and the likelihood of the strategic plan being fully implemented.

The example in figure 3.1 is from Lane Community College in Eugene, Oregon. The infographic clearly shows how the mission drives the plans that lead to key outcomes.

Strategic plans traditionally include the following information:

- Mission and vision statements

- Strengths, needs, barriers, and opportunities assessment

- Long-term goals

- Yearly objectives

- Specific action plans

Agencies will choose the process that works best for them, including determining who should be involved in the process. While traditionally the planning has been made from a top-down perspective, human services organizations are leading the way in involving staff from throughout the agency, community partners, key stakeholders, and service users in the process.

One way to simplify the role of the strategic plan within an agency is to use a human services analogy. Think about what you have learned so far about the concepts of case management and goal setting with a service user. If you think of the agency as a service user receiving case management services, the strategic plan would be the primary service plan for the agency. In case management, you start with an intake process where you learn about the services user and what they want to change. They identify where they are now (mission statement) and where they want to be in the future (vision statement). You help them identify their strengths and areas for growth, along with any potential barriers to their success (strengths, needs, barriers, and opportunities assessment), and then set goals with specific measurable steps and accountability plans (long-term goals, yearly objectives, specific action plans).

Not all agencies have strategic plans. In 2016, the Concord Leadership Group (CLG) published a report called the Nonprofit Sector Leadership Report. They estimated that 49% of the 1006 nonprofit organizations they surveyed did not have written strategic plans (CLG, 2016). Some of the reasons that an agency might not have a strategic plan have already been discussed in this section, such as lack of follow-through on past strategic plans and not having the right people participating in the process. Another reason is the size of the agency. CLG reported that 58% of smaller agencies—those with a budget under $1 million—did not have a strategic plan (2016). In Oregon, 30% of nonprofit organizations have budgets of less than $1 million (Cause IQ, 2022). While there are many benefits to having a strategic plan, it isn’t a requirement.

Here are some questions about strategic plans that you as an intern might find helpful:

- Does the agency have a written strategic plan? If not, do you know the reason?

- Have you read your agency’s strategic plan? Have you asked to read it?

- When did the agency develop the current strategic plan?

- How was the strategic plan developed? Who participated?

- How were service users involved in the development of the strategic plan?

- How frequently does the organization review the strategic plan?

- Does the strategic plan include plans and goals related to diversity, equity, and/or inclusion?

- How does the strategic plan inform your work?

Exploring this information can help you get a feel for how the agency sets—and pursues—its goals and priorities.

Fiscal Solvency

Fiscal solvency refers to an agency’s ability to service any debt as well as meet any other financial obligations. The fiscal solvency of an agency is one of the key indicators of the organization’s health. Note that money wasn’t mentioned. That was purposeful. Having money or the lack of money does not always indicate how an agency is doing. The focus is more on how an agency manages its resources. Public or governmental human services agencies have guaranteed revenue streams and may or may not be fiscally healthy. We will talk more later about whether public agencies are adequately funded. Conversely, private nonprofit agencies have more complicated funding streams that are less predictable. While having adequate funding is important, money alone isn’t the answer.

When referencing agency resources, we are talking about more than money or an agency’s ability to collect, earn, or receive money. Resources are different for private and public agencies. For private agencies, resources include tangible items such as vehicles, property, office equipment, office supplies, products, and agency employees. Resources can also be intangible, and intangible resources need to be managed just as carefully. Agency reputation, staff morale, community partnerships, consumer satisfaction, relationships with the donor base, and social media presence are just a few examples. For public agencies, the agency resources that they can manage are primarily intangible. Technically, a public agency doesn’t own anything—the public does. If a public agency has a budget deficit, it cannot sell off extra office equipment to make up the difference, because they don’t own it—the taxpayers do. What public agencies can manage is their reputation, staff morale, community partnerships, and a limited amount of customer satisfaction.

So how can an intern learn about the fiscal solvency of an agency? Beyond asking your site supervisor to review the financial records, a simple internet search can reveal a great deal. Public agencies are required to make their budgets available to the public for review. For Oregon, public agencies’ budgets are available on the State’s website (State of Oregon, 2021b). Private agencies are required to file a 990 form with the IRS annually to maintain their nonprofit status. Those forms are available for public view, and most can be found at Cause IQ’s website or other watchdog websites. What those forms do not reveal is the budgeting process each agency uses, how the budget is monitored, and who within the agency has the authority to change how the agency resources are utilized.

When assessing an agency for financial solvency, most experts agree that you are looking for a balance of funding sources. For example, if an agency is funded only through fees, there is a risk that a single event, such as a natural disaster in the area, could disrupt their ability to provide the services and eliminate their primary revenue source. If their primary funding source comes from charitable donations, they are at risk for not meeting budget demands during economic downturns. There is no perfect formula because budgeting and managing an agency’s resources is an agency-specific process. Here are some things to look for regarding fiscal solvency:

- Transparency of budget and budgeting processes: Is the budget published on their website? Who is involved in the budgeting process and the budget review process? Is the budget discussed regularly at staff meetings and/or team meetings?

- Asset to debt: Does the agency have the recommended 2-to-1 asset-to-debt ratio?

- Agency endowment and/or reserve funds: Are endowment funds invested to earn interest for the agency? Endowment principal funds cannot be spent; only the interest can. Reserve funds are the monies an agency holds in reserve for potential revenue deficits and fluctuations.

- Wage ratio: How does the highest-paid employee’s salary compare to that of the lowest-paid employee? It should be no more than 3-to-1 for agencies with an annual budget under $5 million and 4-to-1 for agencies with budgets over $5 million.

- Overhead ratio: Is the agency’s overhead less than 25% of its annual budget? Sometimes the overhead ratio can be as much as 35%. Some grants have a limit on how much money can be used for administrative and overhead costs.

Here are some questions about fiscal solvency that you as an intern might find helpful:

- Have you read your agency’s budget?

- How was the budget developed? Who participated?

- How were service users involved in the development of the budget?

- How is the budget monitored? Is the budget discussed at staff meetings?

- Do you know how much the agency keeps in reserve funds? Does the agency have an endowment?

- What are the agency’s most valuable resources that are not monetary?

- Does the budget reflect the mission, vision, and strategic priorities as stated by the agency?

- Does the budget address issues of diversity, equity, and/or inclusion?

- How does the budget inform your work?

These questions may help you see how (or whether) the agency budget aligns with their stated goals.

Private versus Public Agencies

The table below provides a list of both private and public human services agencies and where their money comes from (figure 3.2).

| Private Human Services Agencies | Public Human Services Agencies |

|---|---|

|

|

| Where does the money come from? | Where does the money come from? |

|

|

How Agencies Plan for the Future Licenses and Attributions

“How Agencies Plan for the Future” by Sally Guyer MSW is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.1. “Lane Community College Strategy Map” © Lane Community College and is included under fair use.

Outlines the steps and processes involved in incorporating an agency’s mission, vision, and values into their day to day activities.

the formal summary of why an organization exists, who they serve, and how they are unique.

the formal summary of what an agency or organization wants to achieve.

a governing body of individuals who have been elected, selected, or appointed to oversee an organization.

the verbal, and non-verbal exchange of information between two or more people.

the practice or quality of including or involving people from a range of different social and ethnic backgrounds and of different genders, sexual orientations, etc. that may or may not intersect with each other.

the quality of being fair and impartial and providing equitable access to different perspectives and resources to all students.

the practice or quality of providing equal access to opportunities and resources for people who might otherwise systemically be excluded or marginalized, such as those who have physical or mental disabilities and members of other minority groups.

An agency’s ability to service any debt and meet its other financial obligations.