1.3 Mental Disorders in Modern Times

America, somewhat later, had its own “father of psychiatry,” Dr. Benjamin Rush, who in 1812 would write the first psychiatry textbook to be printed in the United States: Observations and Inquiries Upon the Diseases of the Mind (Penn Medicine, 2017a). In addition to practicing medicine, Rush was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a civic leader who was outspoken in his opposition to slavery and support of education – including the education of girls (University Archives and Records Center, 2022). Some of Rush’s voiced beliefs were in conflict with his actions, however, as he is reported to have engaged in slave ownership for a period (Dickinson College, n.d.). Rush’s progressive views, limited as they were, extended to the treatment of patients with mental disorders.

1.3.1 The Rise of State Hospitals

By the early 1800s, American communities following in European footsteps had developed asylums as well. The higher-end asylums followed the lead of the French doctor Pinel, engaging in what was called moral treatment of patients. Benjamin Rush was a practitioner of this approach. Moral treatment for people with mental illness was based on the idea that ill patients could become well if they were treated kindly, in ways that appealed to the supposed “rational” parts of their minds.

Moral treatment specifically rejected the harsh treatments that had previously been used to respond to mental disorders, as well as the moral judgment or thinking that an ill person was somehow “bad” (Plested, 2017). Instead, the moral approach idealized peace, quiet, and seclusion. American asylums, as opposed to the dungeons of 17th century Europe, were intended to provide this peaceful atmosphere, in hopes of curing their inhabitants (D’Antonio, n.d.).

The active treatments for mental illness offered in American asylums remained very limited in the 1800s. Treatments still included older approaches such as bloodletting, but Dr. Rush himself introduced some new innovations as well. He created a “tranquilizer chair” (figure 1.7) and a gyrator, which would spin restrained patients, in order to encourage better circulation of their blood. The tranquilizer chair especially, though obviously troubling by today’s standards, was a step forward in that it was intended to calm patients by restraining their heads and bodies without the use of a straightjacket (Penn Medicine, 2017b).

Figure 1.7. Benjamin Rush’s tranquilizer chair was intended to calm patients by restricting their movement, as an alternative to using a straightjacket to control the patient.

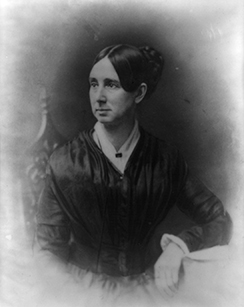

By the mid-1800s, though more expensive private asylums had incorporated moral treatment approaches, many poor American patients with mental disorders still languished in jail-like facilities (D’Antonio, n.d.). This state of affairs inspired school teacher-turned-reformer Dorothea Dix (figure 1.8) to push for change, specifically the establishment of what would be known as state hospitals. State hospitals were psychiatric facilities, in the model of the asylum, funded by the government to serve the public.

Figure 1.8. Dorothea Dix, a reformer and advocate for poor people and those with mental disorders, was instrumental in creating mental hospitals, known as state hospitals, in America.

Dix had reportedly visited jails with the intent of religious outreach, and she became concerned to realize the extent of mental disorders among people who were incarcerated. Recognizing this as a widespread problem in America, she traveled throughout the country during the 1850s and 60s, offering testimony to state legislatures and Congress, urging lawmakers to move people with mental disorders out of jail-like institutions. Dix proposed that states create special, publicly-funded hospitals to house this population. These new facilities imagined by Dix would be dedicated to treatment for those with mental illness, and she believed they offered the opportunity for better treatment, and even cures, for many patients. Dix’s advocacy contributed directly to the creation of more than 30 state hospitals. By 1870, nearly every state had a public hospital or asylum, built on the principles of moral treatment (D’Antonio, n.d.; Parry, 2006).

Dix’s advocacy and her results were impressive. However, over time it became clear that the new facilities promised more than they were able to deliver. State hospitals were indeed an improvement over previous facilities, but they offered no actual cure to most of their inhabitants (Tracy, 2019). In fact, the hospitals were increasingly used to house additional populations – such as the elderly or people with disabilities – who needed state-funded care, but who were not moving toward “recovery.” The state hospitals began to exceed their capacity and their limited resources, full of patients who really needed care for their entire lives (D’Antonio, n.d.).

By the late 1800s, state hospitals were showing their overwhelm. They were overcrowded, increasingly filthy and offered very little in the way of actual treatment to their residents. (Spielman, Jenkins & Lovett), (Farreras). The practice of institutionalization, or keeping people with disabilities or mental illness in facilities rather than integrated into communities, was firmly entrenched. (Spielman, Jenkins & Lovett) Ultimately, the new hospitals championed by Dix were simply the latest way to confine and remove this population that was unwelcome in American society.

Stories of the horrors at state hospitals abound – and could fill an entire textbook. One example, the Willard Psychiatric Center, originally called the Willard Asylum for the Insane, first opened in 1869 and remained open for 130 years (New York Heritage, n.d.). At Willard, in upstate New York, reported “treatments” included submerging patients in ice-cold baths – while wintertime temperatures in the facility were said to be cold enough to freeze a glass of water left on a table overnight. (Willard Psychiatric Center, 2009; Spielman, Jenkins & Lovett).

Willard was not alone in its miserable treatment of patients; rather it was typical of state institutions at the time. Reports on other similar hospitals reveal that people were often treated cruelly – with reported beatings, sexual abuse, and experiments performed on unknowing residents (Brown, 2021). Since every state had built an institution for its mentally ill and/or disabled residents, nearly every state has a history of an abusive institution that existed for decades, at least, extending into recent history. Some of these histories remain more obscure than others, with residents often not able to express and publicize their experiences.

Oregon had its own infamous institutions, including the Fairview Training Center. Over the course of its life, Fairview confined thousands of people, from young children to elderly, with a range of disabilities that often included mental disorders. Fairview opened in 1908 as “an institution for the feeble-minded, idiotic, and epileptic,” with 39 “inmates.” It eventually became Oregon’s largest institution, housing 3000 residents at its peak. Fairview residents were restrained, whipped, drugged, and locked into small cages. Disabled children often entered Fairview and remained confined there for their entire lives. Thousands of Fairview residents endured forced reproductive sterilizations that continued to occur through the 1970s (James, 2015). Watch the video in figure 1.9 to hear from Fairview residents themselves who were victims of this practice.

Figure 1.9. Eugenics: In the Shadow of Fairview [OPB Video]. This short video clip from the longer documentary “In the Shadow of Fairview” highlights the story of the 2600 Oregonians who underwent forced sterilization due to their disabilities while at or trying to leave Fairview Training Center. See Spotlight on Carrie Buck later in this chapter, for additional information on the legality of forced sterilization.

Fairview remained operational (and overcrowded) well into the 1980s, despite advocacy by the oppressed residents, sanctions for mismanagement and abuse of the people it housed, and even a U.S. Department of Justice investigation in 1985. Fairview finally began to move residents out, but it stubbornly remained open until 2000. The institution downsized to 1500 residents in 1986, and to 300 by 1996 (Drummond, 2000). For more information on Oregon institutions, see the Spotlight in this chapter on the Oregon State Hospital.

1.3.2 SPOTLIGHT: Carrie Buck and the Practice of Eugenics

Of the many violations experienced by people with mental disorders, forced limits on their reproductive abilities remains one of most hurtful and lasting impacts of a time when this population was deprived of even the most basic human rights.

The reproductive sterilization movement in the United States took off in the 1890s. Proponents of forced sterilization argued that certain “unfavorable” characteristics in the gene pool were hereditary. Under that reasoning, it made sense to policy-makers that sterilizing people with these characteristics would eventually remove those genes from the population. Interference with and control of reproduction for these reasons is called eugenics.

Inmates of institutions with a variety of mental disorders (such as developmental disorders) and medical conditions like epilepsy were considered unfavorable to the human race and thus became targets of sterilization programs. At the time, more than a century ago, terms such as “feebleminded” were used to describe these people, and legally, these terms needed to be defined. As early 1900s fate would have it, a woman could be considered feebleminded if she was involved in prostitution, if she were to have intercourse while unmarried, and especially if she were to become pregnant out of wedlock. This brings us to the notable U.S. Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell.

In the fall of 1923, Carrie Buck (figure 1.10) was a 17-year-old foster child living in the state of Virginia. Her foster mother realized that Carrie was pregnant. She and her husband decided the best thing to do was to institutionalize Carrie for being an unwed teenage mother, despite the fact that this unplanned pregnancy was the result of a rape. Carrie’s condition was a sign that she was morally delinquent and thus “feebleminded.” Carrie’s baby was considered feebleminded upon her birth, having been born to a feebleminded mother, and was eventually adopted by Carrie’s former foster parents. Meanwhile, Carrie was sent to the Virginia Colony where she was reunited with her own mother, Emma Buck, who had also been institutionalized for feeblemindedness.

Figure 1.10 Carrie Buck, during the time she was institutionalized.

Carrie Bell was the first woman to be sterilized under Virginia’s 1924 Eugenical Sterilization Act. When this plan was challenged by a caregiver, it was examined by the Virginia courts and eventually approved by the United States Supreme Court in Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927). The Court approved Carrie Buck’s sterilization enthusiastically, comparing the procedure to a preventative health measure, like vaccination. This Court decision served to empower the eugenics movement in America, which ran its course from the 1890s through the 1970s.

Virginia went on to sterilize 8,300 people, but the practice was happening all over the country. Oregon passed an eugenics bill in 1913 and established an official Board of Eugenics in 1923. This board was later renamed the Board of Social Protection and remained intact until its abolition in 1983. Oregon forced sterilization on people with mental disorders at its Fairview Training Center, as discussed in the text, in addition to others – such as people identified as criminals and homosexuals. Youth in reform schools and young girls considered to be promiscuous were also sterilized as part of this movement. Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber issued a formal apology to Oregon’s 2,648 victims of forced sterilization in 2012.

Josefson, D. (2012). Oregon’s governor apologises for forced sterilisations. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1170108/#:~:text=In%20a%20historic%20gesture%20Oregon’s,were%20criminals%2C%20or%20were%20homosexual..

Antonios, Nathalie,, Raup, Christina, “Buck v. Bell (1927)”. Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2012-01-01). ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/2092.

Given that institutionalization of people with mental disorders was in place during a time of widespread racial segregation in America, there were also state hospitals, or sometimes parts of hospitals – such as basements – dedicated to housing Black patients. Though the Civil Rights Act of 1866 required state hospitals to accept Black patients, many completely refused to do so, and where they were admitted, they were segregated from white patients (Swenson, 2017). Virginia’s “Central Lunatic Asylum for the Colored Insane,” later known as Central State Hospital, was filled in the late 1800s with Black patients housed in primitive and abusive conditions. All of the women in the facility were guarded by men, based on the thinking that the women needed guards with enough strength to properly control them. Many of the Central State residents had been deemed mentally ill and fit for institutionalization based on nothing more than accusations by racist whites, unhappy with the free status of a former slave. Some were declared insane based on their simple desire to be free (Brumfield, 2021). Indeed, during the period of slavery, Black people had been routinely found to be mentally ill simply for desiring or attempting to escape enslavement (Swenson, 2017).

Patients in any early American institutions rarely received humane care or treatment for mental illness, or whatever disorder had led to their hospitalization, but this failing was especially pronounced for Black patients. These patients endured particularly dehumanizing treatment based on race. In records from the Central State Hospital, detailed notes about patients were almost always summaries of their “usefulness” – that is, their ability to work. Former slaves both in and out of institutions were considered valuable only to the extent they could be part of a planned cheap labor force in the post-slavery era (figure 1.11; Swenson, 2017).

Figure 1.11. This photo of Black women in the Central State Hospital shows them engaged in “diversional occupation.”

1.3.3 Treatment of Mental Disorders in the 1900s

During the mid-1900s, treatments offered to patients in state hospitals had expanded beyond bloodletting, but these treatments remained in experimental stages. Mentally ill and disabled people in institutions suffered the burden of trial and error. Modern electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which involves passing small electric currents through a patient’s brain, is performed under anesthesia with safeguards in place. ECT creates changes in brain chemistry that have been highly effective in treating conditions such as severe depression (Mayo Clinic, 2018). The original version of this treatment, however, known as electroshock therapy, induced seizures with large amounts of electricity. The procedure was done without anesthesia, and it was violent and dangerous. A patient described the experience of electroshock therapy at the Missouri state hospital in 1957:

Patients were generally on [electroshock] treatment twice a week . . . . Begging, pleading, crying, and resisting, they were herded into the gymnasium and seated around the edge of the room.

Between them and the shock treatment table was a long row of screens. The table on the other side of the screen held as much terror for most of these patients as the electric chair in the penitentiaries did for criminals… In order to save time, one or more patients were called behind the screen to sit down and take off their shoes while the patient who had just preceded them was still on the table going through the convulsions that shake the body after the electric shock has knocked them unconscious.

One attendant stands at the head of the table to put the rubber heel in their mouth so they won’t chew their tongue during the convulsive stage. On either side of the table stand three other attendants to hold them down . . . (Missouri State Archives, 2003)

Likewise, early brain surgeries to cure mental disorders were ill-advised and often devastating. These procedures were predecessors to modern surgical approaches to brain disorders, which are very promising in certain cases, such as severe epilepsy – but the practices and goals were quite different. Lobotomies, where part of the brain would be removed with a goal of managing or curing mental illness, were performed on patients up until the 1950s in America (Tracy, 2019). Perhaps the most famous recipient of a lobotomy was Randle McMurphy, the fictional hero of Ken Kesey’s 1962 anti-psychiatry novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, set at an Oregon psychiatric institution. Kesey’s book came out as civil rights activists were questioning all aspects of establishment and authority in America – including the state hospitals.

Rosemary Kennedy, the sister of eventual President John F. Kennedy, was subjected to a lobotomy as a young woman (figure 1.12). Rosemary’s father, Joseph Kennedy, reportedly ordered the lobotomy, which occurred in 1941 when Rosemary was in her early 20s. As a result of the surgery, she was gravely disabled (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, n.d.). It was believed that Joseph Kennedy’s request was motivated by Rosemary’s disruptive behavior that caused the family embarrassment and threatened the Kennedy males’ political careers (Gordon, 2015). Rosemary was influential largely because of the impact her surgery and ensuing disability had on her powerful and famous siblings; she herself was hidden from public view and was cared for in an institution away from even her family for most of her life.

Figure 1.12 is a photo of Rosemary Kennedy, who was given a lobotomy by doctors at the direction of her father, Joseph Kennedy (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, n.d.).

1.3.4 SPOTLIGHT: The Oregon State Hospital, Then and Now

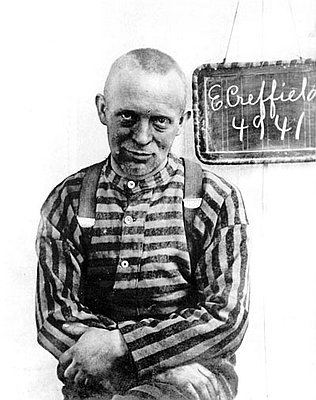

After Corvallis-area cult leader Edmund Creffield (figure 1.13) was convicted on charges of adultery, most of the members of the Brides of Christ Church were committed to what was then called the Oregon State Insane Asylum in Salem. The diagnosis was “religious hysteria,” and the women were committed by concerned family members. The year was 1904, and the Asylum had only been in operation since 1883.

Figure 1.13. Edmund Creffield, shown in an Oregon State Penitentiary photo around 1904. Follow this link for more of Creffield’s fascinating story.

The Oregon State Insane Asylum was, at the close of the 1800s, considered a safe place for people to take their family members for many reasons, in addition to supposed insanity. Some had committed crimes, others were developmentally disabled, and many others may have simply been seen as a burden to society. A report released by the Oregon State Insane Asylum in 1896 listed the various “causes for insanity” among those admitted between December 1894 and November 1896. Among these reasons were things such as business trouble, financial trouble, loss of sleep, menopause, and even masturbation (Mentalhealthportland.org, 2012).

Purportedly, asylum patients could receive treatment and rehabilitation, and then return back to society. Unfortunately, a mental institution’s idea of “treatment” back in the 1800s and early 1900s was often more detrimental than helpful, and many abuses occurred. Among these treatments were lobotomies, ice baths, electroshock therapy, straightjackets, sedation, and even forced sterilization.

By the middle of the century, it became apparent that the Oregon State Insane Asylum wasn’t large enough to house all of the Oregonians in need of inpatient mental health services. By 1958, the Oregon State Insane Asylum was vastly overcrowded with 3,545 patients, causing already-horrific conditions to be even worse. This led to the opening of several new mental health facilities around the state, and the Asylum officially changed its name to Oregon State Hospital.

Fortunately, as science and medicine have made advances, so has our understanding of effective treatments for mental disorders. Psychiatric facilities such as the Oregon State Hospital no longer administer lobotomies or any of the other horrific “treatments” that were once the norm. Treatments for mental disorders now often include medications, supplemented by individual and group therapies and activities.

As discussed in more depth in the main text, psychiatric hospitals that remain in operation have improved vastly since the time of their inception. However, the overall mental health system in the United States, including Oregon, has floundered since deinstitutionalization, or the widespread closure of the old version of these hospitals. Recognizing the inadequacy of community mental health supports, Oregon has renewed its commitment to this population – at least for the moment. In the 2021-2022 legislative session, Sen. Kate Lieber and Rep. Rob Nosse passed large investment packages for Oregon’s behavior and mental health system. A combined total of $1.25 billion will be invested in substance abuse programs, mental health treatment, and therapeutic housing options. With any luck, these new services will ensure those Oregonians who need these services will be able to access them when they need them, and receive the best care possible.

The History of the Oregon State Hospital from 1883-2012. Mentalhealthportland.org. Retrieved from http://www.mentalhealthportland.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/The-History-of-the-Oregon-State-Hospital-from-1883-2012.pdf.

Porter, L. (2022). Straight Talk: Lawmakers call a $1.25 billion investment in Oregon’s behavioral health system the beginning of turning around a neglected system. KGW8.com. Retrieved from https://www.kgw.com/article/entertainment/television/programs/straight-talk/straight-125-billion-investment-oregon-behavioral-health-system-historic/283-e81b49d7-8b4c-4705-9b87-61b5e6a3f046.

1.3.5 The Decline of Mental Hospitals

Significant changes to the American approach to mental disorders, and to the status quo of institutionalization, began to occur in the 1940s. President Harry Truman signed the National Mental Health Act in 1946, leading to the creation of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) a few years later. Over the next decades, the NIMH significantly expanded America’s commitment to use science to understand and treat mental illness (National Institute of Mental Health, 2021). Scientific progress would, eventually, lead to opportunities for treatment of mental disorders outside of hospitals.

The idea of asylums, and state hospitals, had been to provide care via a sheltering environment, which necessarily removed people with mental disorders from their communities. Also, while primitive brain surgeries and shock therapy had many drawbacks, one was that they could not be accessed in the community – these were hospital-based treatments. Thus, a most revolutionary scientific development in treating mental disorders was the development of psychiatric medications. Unlike previous procedures and treatments that could only be performed in hospital settings, medications that treated mental disorders could be used in the community. And where severe symptoms might have required confinement of patients, medications to control symptoms of mental illness alleviated that need for confinement. Just as many activists were beginning to question the routine institutionalization of people with mental disorders, medication management provided an opportunity to end this approach.

In 1949, lithium was introduced as the very first effective medication to treat mental illness, specifically what is now known as bipolar disorder (Tracy, 2019). Another critical breakthrough occurred in 1952, when the first antipsychotic medication, chlorpromazine, became publicly available. Antipsychotic medications treat psychosis, a debilitating aspect of mental illness that impacts a person’s ability to distinguish what is real. People experiencing psychosis may have delusions, where they believe something that is not real, or hallucinations, where they see or hear things that do not exist. Antipsychotic drugs treat and help control these symptoms – allowing a person to again perceive reality (National Institute of Mental Health, 2022). Chlorpromazine, marketed and more commonly known as Thorazine, effectively (though not completely) controlled symptoms of psychotic illness in many patients (Tracy, 2019).

Fueled by the scientific successes of the late 1940s and 1950s, as well as the growing activism against institutional treatment of mental disorders, the Community Mental Health Act (CMHA) was passed by Congress in 1963. President John F. Kennedy, whose sister had undergone a lobotomy twenty years earlier, signed it into law (figure 1.14). The CMHA promised federal support and funding for community mental health centers (National Institutes of Health, 2013). This legislation (along with some of the other laws discussed in Chapter 3 of this text) was intended to change how services for mental disorders were delivered in the United States. Specifically, the CMHA meant to shift mental health care to communities, bringing patients along to live safely in those communities.

Figure 1.14. President John F. Kennedy signs the Community Mental Health Act into law in 1963. Oregon Representative Edith Green is in the background, with other lawmakers.

The signing of the CMHA was done with hope and good intentions for reducing institutionalization of all people with mental disorders – those with mental illness as well as people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. In a speech to Congress promoting his agenda, President Kennedy described a plan that would change the landscape for people with mental disorders:

I am proposing a new approach to mental illness and to mental retardation.[1] This approach is designed, in large measure, to use Federal resources to stimulate State, local and private action. When carried out, reliance on the cold mercy of custodial isolation will be supplanted by the open warmth of community concern and capability. Emphasis on prevention, treatment and rehabilitation will be substituted for a desultory interest in confining patients in an institution to wither away.

John F. Kennedy, Special Message to the Congress on Mental Illness and Mental Retardation, February 5, 1963 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021).

The CMHA anticipated the building of 1500 mental health centers in communities, which would allow half of the nearly 600,000 people with mental disorders who were then institutionalized in state hospitals to be treated, instead, in their homes and communities (Erickson, 2021). While the CMHA did help connect many people with community-based treatment, and psychiatric hospitalizations decreased drastically in the ensuing years, the law did not meet its full promise. Only half of the expected mental health centers were ever built, and funding proved inadequate for the ones that were created. Though the CMHA provided dollars to build the mental health centers, it did not provide continuous funding to run them, expecting states to step up with support. States, though, were quick to reduce their own contributions when funding was tight or other priorities were more politically popular (Smith, 2013).

Critics argue that the CMHA was an example of “optimism without infrastructure” (Erickson, 2021). The CMHA was well-intentioned, hopeful even, but there were failures in executing its plans; in the end, not nearly enough community support was available for people to quickly leave institutions, or to get the help they needed when they did leave. This was particularly true for people with more serious or severe mental disorders.

1.3.6 Licenses and Attributions for Mental Disorders in Modern Times

“Mental Disorders in Modern Times” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Reliance on “Psychology 2e, 16.1- Mental Health Treatment: Past and Present ” by R. M. Spielman, W. J. Jenkins & M.D. Lovett, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Spotlight: The Oregon State Hospital: Then and Now” by Monica McKirdy is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Spotlight: Carrie Buck and the Practice of Eugenics by Monica McKirdy is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.7. Benjamin Rush’s Tranquilizing Chair: National Library of Medicine, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 1.8. Dorothea Dix, a reformer and advocate for poor people and those with mental disorders, was instrumental in creating mental hospitals, known as state hospitals, in America. https://openstax.org/apps/archive/20220815.182343/resources/786d97164070b11e752032847da5beec8b02071e

Figure 1.9. “Eugenics: In the Shadow of Fairview” [clip of Season 15 Episode 1] by OPB is included under fair use.

Figure 1.10. Photograph of Carrie Buck at the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, taken by A.H. Estabrook before the Buck v. Bell trial in Virginia, is in the public domain.

Figure 1.11. Photo of Black women in the Central State Hospital is in the public domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7f/Diversional-occupation-csh.jpg

Figure 1.12 Photo of Rosemary Kennedy, https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/the-kennedy-family/rosemary-kennedy, included under fair use.

Figure 1.13. Photo of Edmund Creffield at Oregon State Penitentiary, c. 1904., Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46627349

Figure 1.14. Photo by Cecil Stoughton is in the Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Mental retardation was the medical term that predated the modern and preferred term intellectual disability. As retardation became used as a slur, drawing on the nearly universal societal disdain for people with intellectual disability, the term was rejected by disability self-advocates, and eventually the general public, as well as the legal and medical establishment (Social Security Administration, 2013). ↵