5.2 Policing Mental Disorders

Policing post-deinstitutionalization has presented many challenges – including increased burdens on the police force and risks for the people they are policing. As discussed in Chapter 1, many people were released from psychiatric hospitals to be treated in the community, with the benefits of modern medical treatments and social safety nets. Many of these people thrived, but others – particularly those who experienced more severe mental illness – did not get the supports they needed (housing, health care, case management) to succeed. States did not fund community mental health centers that had been planned to replace hospital care. Meanwhile, substance use disorders increased by staggering amounts in most places, through the 1980s into the present day, with inadequate treatment available across the board.

In the face of these demands, police departments have had to develop increased training and staffing capacity for addressing mental health and substance use in their communities. Police officers need a heightened awareness and concern for people with mental disorders, including mental illness, substance use, and developmental disabilities, whom they may encounter in their work. This section covers several types of policing initiatives intended to help them meet these challenges more effectively and safely for all concerned.

5.2.1 Speciality Units Within Policing

Police bureaus across the United States have developed speciality units to address specific needs in their communities. These speciality units vary among police departments and needs identified by the community. One need identified has been the productive and safe engagement of people with mental disorders, and departments are increasingly looking to police-mental health collaborations to satisfy this need. The Department of Justice has encouraged development of such programs and offers a toolkit and funding opportunities to encourage their development.

In Oregon, the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) has developed the Behavioral Health Unit (BHU), which consists of four tiers of police response to assist people in the community struggling with a behavioral crisis involving a known or suspected mental disorder or substance use disorder. While all Portland Police receive mental health response training, certain BHU officers have “enhanced” training on mental disorders and deescalation tactics, beyond that provided to officers in general. These officers with enhanced training serve in a voluntary capacity on teams that can be dispatched to situations requiring these particular skills and techniques (Portland Police Bureau, n.d.).

A co-response approach is also used by PPB, partnering with Cascadia Behavioral Health Services, as part of the continuum of tactics in PPB’s BHU. In practice, PPB’s co-response approach involves a concerned community member calling the police. If the subject is known to have mental health needs or the concerned community member reports indicators of a mental disorder, police may have mental health professionals assist in the response. Specifically, police may remain at a safe distance from the subject while the mental health professionals respond to the concern. If they are able to resolve the situation, then no police intervention is needed. If the situation becomes dangerous or escalated, police are nearby to respond accordingly.

In Figure 5.2, the five-minute video shows an example of the work PPB’s Behavioral Health Unit provides to those struggling with mental health needs in the Portland metro area. This film shows a ride-along with Officer Josh Silverman and takes a brief look at a typical day for BHU’s Mobile Crisis Unit.

Figure 5.2. Ride Along with the Portland Police Bureau’s Behavioral Health Unit [YouTube Video]. Portland Police Bureau’s Behavioral Health Unit works to take a different approach to policing that can more effectively serve the community and those experiencing mental disorders.

5.2.2 Crisis Intervention Training (CIT)

In addition to development of specific response units, police departments have developed training programs to qualify their officers to respond appropriately and safely to community members with a variety of mental disorders. The most well-known of these training approaches, Crisis Intervention Training (CIT), is also known as the “Memphis Model.”

CIT training was first developed in response to public outcry after a Memphis police killing of an apparently suicidal young Black man, Joseph DeWayne Robinson, in 1987. Details are predictably scarce as to Robinson’s story, but it seemed clear after his death that his only weapon was a knife, and likely his only intent was to hurt himself. He was shot by police when he did not drop the knife per their demands (Connolly, 2017).

According to a 2016 New York Times article, “twenty-five percent or more of people fatally shot by police, have had a mental disorder” (Goode, 2016). More recent studies have placed the number even higher, and horrific incidents have continued. In October of 2022, the family of Daniel Prude, a Black man experiencing an apparent drug-involved mental health crisis, was killed by police in an encounter where he was held, naked, in the street and suffocated in a “spit hood” that was placed on him while he was held on the ground. Prude’s family settled a multi-million dollar lawsuit against the Rochester, New York police department who was found liable for his death, based on a failure to properly train its officers in managing a situation like Prude’s (Clifford, 2022).

The goal of CIT, when it was developed and as it is used in law enforcement settings nationwide, was to prepare officers for encounters like those with Robinson and Prude (and many others) in hopes of better outcomes. One training technique, for instance, is to change the way officers approach people with mental disorders and teach officers how to defuse potentially violent encounters before use of force would become necessary (Goode, 2016). CIT training has also been cited as reducing officer injuries in mental health crisis calls by eighty percent (National Alliance on Mental Illness, n.d.).

The Portland Police Bureau, faced with the horrific 2006 killing of James Chasse (See Spotlight in this Chapter) and an ensuing Department of Justice investigation alleging a pattern of excessive use of force against people with mental disorders, embraced CIT training for all of its officers, later adding the enhanced training for additional officers discussed earlier. However, CIT training still gets mixed reviews in terms of results, especially as experts recognize it takes more than the current standardized 40-hour training to make change. Change comes with a culture shift that goes beyond what a 40-hour training provides. Change must come from police bureau leadership, from the remainder of the criminal justice system (e.g. prosecutors and judges), and from on-going collaboration with community behavioral health specialists.

5.2.3 Public Safety Strategy

In Oregon, the Department of Public Safety and Standards Institute (DPSST) is a training program for police officers, firefighters, first responders, 911 dispatch, and correctional officers. Every Oregon law enforcement officer, from every state and local agency, attends a 16-week academy through DPSST where they are trained on a variety of topics including: DUII response, search warrants, firearm training, and more. DPSST has also incorporated trainings on domestic violence, sexual assault, and human trafficking into the curriculum. Oregon takes great pride in its DPSST programs, which have been required by Oregon law since 1961 and incorporate a significant amount of scenario-based and hands-on trainings of the sort most observers want for law enforcement officers (Gabliks, n.d.).

While the DPSST training incorporates information about mental disorders, the number of training hours dedicated to this topic is small compared to the number of encounters law enforcement officers will inevitably have with people with mental disorders – as well as the potential high-stakes nature of these encounters.

DPSST training sections on mental disorders are reviewed by mental health professionals; however, these sections, along with many others, are taught by retired law enforcement officers. Experienced trainers in law enforcement are critical, however there is a missed opportunity when new law enforcement officers are trained primarily by seasoned officers. Holistic approaches at police academies are critical to provide law enforcement with various perspectives on what it means to serve and protect a community. Without facilitation and input from behavioral health professionals, community members, and people with mental disorders who have had police encounters,new officers entering the field of policing are not as well-served as they might be by standard DPSST training.

5.2.4 Guidelines for Encounters

Encounters with people with mental disorders are not necessarily more likely to escalate into violence than are encounters with people without mental disorders. It is a common misconception that people with mental disorders are more violent, generally, than people who do not experience mental disorders. In fact, people with mental disorders are not more violent. People with mental disorders and developmental disabilities need to be treated with compassion, patience and support when trying to convey information. It is never the goal to escalate situations, the goal should always be to use techniques to de-escalate situations wherever possible.

5.2.4.1 De-Escalation

De-escalation, or reduction in intensity or conflict, is an essential technique in the criminal justice field, where professionals are likely to consistently find themselves in tense and stressful, and even dangerous, situations. The goal of de-escalation is to bring a person back to their baseline, and away from an intense state where they may be unreasonable and unpredictable – due to panic or anger or other triggers, so that use of physical force is not required.

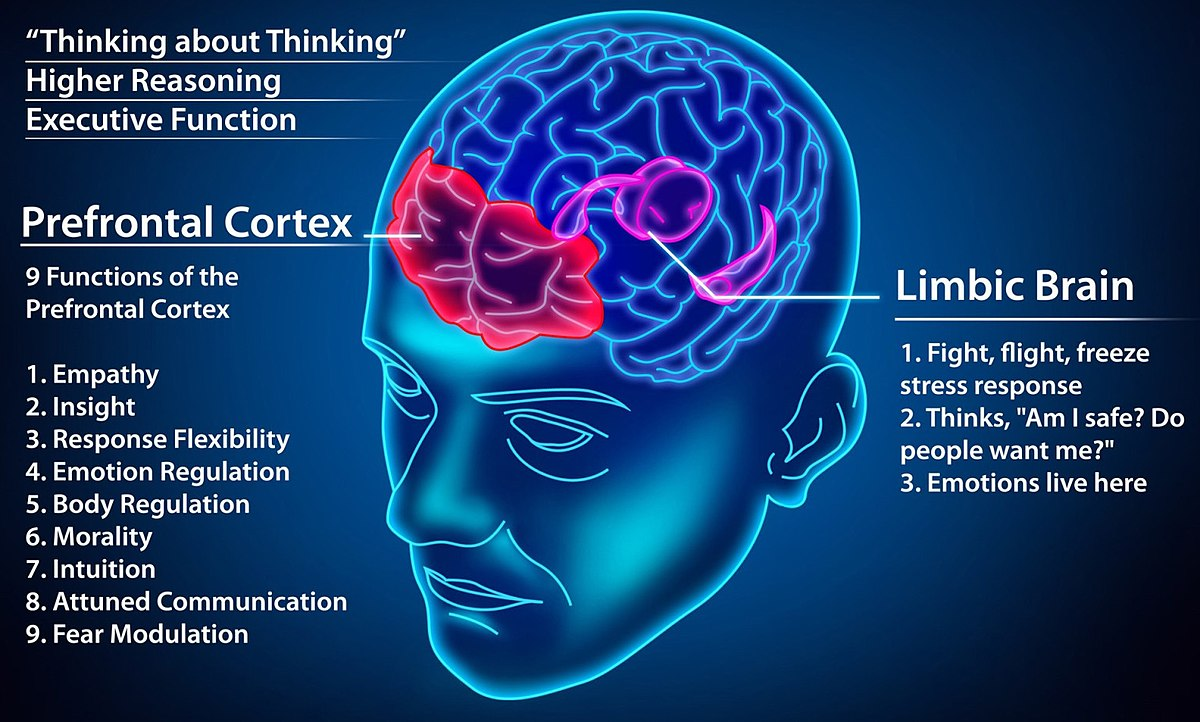

The first step in de-escalating a situation is to remain calm. Using your breath and your own coping skills to maintain a sense of calm will go far. People absorb external, escalating stimuli which causes their prefrontal cortex (i.e. rational brain that helps us make decisions and solve complex problems) to turn off. What is left to function is a person’s amygdala (i.e. fight, flight, or freeze part of the brain). When someone’s amygdala is activated, they cannot make rational decisions until their prefrontal cortex comes back online. The goal of de-escalation is to use skills to calm the amygdala and reactivate the reasonable prefrontal cortex.

Figure 5.3 shows the prefrontal cortex or the higher reasoning part of one’s brain and the limbic brain, which is the part of the brain that functions for survival in a stressful situation.

De-escalating a situation – as you are sharing your calmness with a very upset person – requires that you use assertiveness skills, that may include both physical and verbal assertiveness.

Physical assertiveness is generally taught as displaying a strong posture, firm stance, and open body language. Interacting with an panicked or very angry person is not the time to fold your arms together, slouch down, cross your feet, or divert your eye contact. It is a time to display calm body language, but also demonstrate authority. This approach includes being mindful of your movements and being sure to not raise hands above waist level or make sudden movements.

Physical assertiveness is also positioning yourself for safety. Throughout your career, it is very important to always be aware of your exits when meeting with someone where the situation could potentially escalate. You should always be closest to an exit and know how to re-position for safety if a situation escalates. For instance, if someone is becoming out of control when meeting in an office setting, move to safety by slowly making your way to the door. You can also position yourself so that a piece of furniture is between you and the person who may be a threat.

Verbal assertiveness is maintaining a sense of calm, and helping control a situation, with your voice. You may need to raise your voice initially to get an escalated person’s attention (e.g. call out their name), and then slowly bring your voice down, so the person must lower their voice in order to hear you speak. Verbal assertiveness includes using clear and short sentences with some form of directive. A directive to give to an escalated person may be, “I need you to step out of the doorway and let me pass.” It may also be something more direct to maintain your safety. For example, “put the knife down and step away from the kitchen.” When someone is in a heightened emotional state, they cannot comprehend complex sentences or complex problem solving; short sentences and precise directives can go far when working to deescalate a situation, verbally.

After skills have been used to effectively de-escalate a situation, it is important to rest and take care of yourself. De-escalating someone can be time-consuming and emotionally exhausting for the person tasked with de-escalating the encounter. Your body will have likely had an emotional and physical response to being around an escalated person, which could leave you tired and feeling drained. All these feelings are common after responding to an escalated situation (City of Portland, n.d.).

Most de-escalation training is, naturally, taught by and for men – who still make up the vast majority of law enforcement professionals. Women make up less than 15 percent of full time law enforcement officers in the United States (Van Ness, 2021). Commenters have observed that women may more naturally tend to deescalate situations, perhaps stemming from the physical reality that most cannot actually muscle their way out of confrontations and may be socialized throughout their lives to work as peacemakers. Female-presenting officers may more naturally rely on their voices, their reason, and their empathy to deescalate situations. These techniques may look and feel different in some ways from those discussed above – which are traditionally used and passed along in the current male-dominant law enforcement culture. Some advocates suggest that a substantial increase in women on police forces might be critical to truly changing the culture of policing. Women officers are statistically less likely to use excessive and deadly force than male officers, and so are male officers who work alongside them (Naili, 2015). However, even where police increase their female employees, racial disparities in arrests and other measures are not improved (Corley, 2022). In order to be truly effective, deescalation strategies need to be developed, and provided to officers, with the traits of the individual officer in mind, as well as the traits (gender, culture, disability status) of the person with whom they are working.

5.2.4.2 Use of Force

Use of force situations are the last resort when de-escalation encounters have been unsuccessful. Most law enforcement agencies have use of force policies. These policies describe an escalating series of actions an officer may take to resolve a situation. This continuum generally has many levels, and officers are instructed to respond with a level of force appropriate to the situation at hand, acknowledging that the officer may move from one part of the continuum to another in a matter of seconds.

An example of a use-of-force continuum follows:

-

Officer Presence — No force is used. Considered the best way to resolve a situation.

-

The mere presence of a law enforcement officer works to deter crime or

diffuse a situation. - Officers’ attitudes are professional and nonthreatening.

-

The mere presence of a law enforcement officer works to deter crime or

-

Verbalization — Force is not-physical.

-

Officers issue calm, nonthreatening commands, such as “Let me see your

identification and registration.” -

Officers may increase their volume and shorten commands in an attempt

to gain compliance. Short commands might include “Stop,” or “Don’t

move.”

-

Officers issue calm, nonthreatening commands, such as “Let me see your

-

Empty-Hand Control — Officers use bodily force to gain control of a

situation.-

Soft technique. Officers use grabs, holds and joint locks to

restrain an individual. -

Hard technique. Officers use punches and kicks to restrain an

individual.

-

Soft technique. Officers use grabs, holds and joint locks to

-

Less-Lethal Methods — Officers use less-lethal technologies to gain

control of a situation.-

Blunt impact. Officers may use a baton or projectile to

immobilize a combative person. -

Chemical. Officers may use chemical sprays or projectiles

embedded with chemicals to restrain an individual (e.g., pepper

spray). -

Conducted Energy Devices (CEDs). Officers may use CEDs to

immobilize an individual. CEDs discharge a high-voltage, low-amperage

jolt of electricity at a distance.

-

Blunt impact. Officers may use a baton or projectile to

-

Lethal Force — Officers use lethal weapons to gain control of a situation.

Should only be used if a suspect poses a serious threat to the officer or

another individual.-

Officers use deadly weapons such as firearms to stop an individual’s

actions.

-

Officers use deadly weapons such as firearms to stop an individual’s

5.2.5 Licenses and Attributions for Topic 1

DPSST Section attributed by Ashley Anstett.

De-escalation section attributed by Kendra Harding. Pieces of this section was learned through Portland Police Bureau Women Strength Programs developed by Sara Johnson (Introductory Self-Defense Classes | Class Schedules | The City of Portland, Oregon (portlandoregon.gov))

Behavioral Health Unit | Portland.gov

Figure 5.1 Ride Along with the Portland Police Bureau’s Behavioral Health Unit – YouTube

Use of Force: Copied verbatim from:

National Institute of Justice, “The Use-of-Force Continuum,” August 3, 2009, nij.ojp.gov:

https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/use-force-continuum

For Police, a Playbook for Conflicts Involving Mental Illness – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Learning | Bureau of Justice Assistance (ojp.gov)

Brain image (CC-BY-4.0)File:Blog prefrontal cortex.jpg – Wikiversity

Figure 5.3 “Trauma brain” by Jan Edmiston, A Church for Starving Artists is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0.