6.3 Insanity as a Criminal Defense

The first section in this chapter discussed scenarios where an accused person’s mental disorder impacts their ability to navigate the court process. Backing up in time, the person’s mental state when they committed the offense (often months or years prior to resolution of the case) can be an important factor in how the case is ultimately resolved. The lack of mental capacity to commit a crime is a rare but important defense to criminal conduct. When a person asserts the insanity defense, they admit that they did the accused act, but they assert (and must prove) that they are not guilty of a crime due to the influence of their mental disorder.

The mere presence of a mental disorder does not make a person legally “insane” for purposes of the insanity defense. A mental disorder is a medical diagnosis – schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, intellectual disability, and so on. People who have these diagnoses live productive and pro-social lives in our communities, and, sometimes, people with these diagnoses engage in criminal behavior for which they should be held accountable. But occasionally – rarely – certain mental disorders can render a person legally insane under the law in their jurisdiction, and that insanity can provide a defense to otherwise criminal conduct.

When a person is found not guilty by reason of insanity, or guilty except for insanity (GEI) as it is called in Oregon, the result of this verdict is generally that the person is committed to the care of a state mental health provider, usually a state hospital for more serious offenses. Care may be ordered for an indeterminate period of time or, as it is done in Oregon, for a designated time period. In Oregon, the person may be, and often is, committed for the maximum time allowed for a prison sentence if the person had been convicted of that particular offense. So, if a person in Oregon is found GEI for a burglary of a residence, they may be committed to the state hospital for up to 20 years. Although this type of commitment, discussed in more detail in Chapter 9, may feel or look like a punishment, the order is not a criminal “sentence,” as the person has not been convicted of a criminal offense. Rather, the objective is to provide care and minimize the person’s danger to others as well as themselves.

6.3.1 Excuse vs. Justification Defense

Insanity is in the category of defenses where the person admits they did the harmful act at issue, but circumstances surrounding the act remove criminal responsibility – or criminal guilt – for the act. The two groups of defenses in this category are justification defenses and excuse defenses:

- Justification defense: the accused person has committed no crime because their behavior was warranted, or justified, by the circumstances. The classic example is self-defense: the accused person was being attacked, and they killed the alleged victim (the attacker) in order to save their own life. The accused has not committed a crime; they were defending themselves.

- Excuse defense: the accused person has done something wrong, but bears no criminal responsibility due to the circumstances of their action. Examples might include duress (offender was forced to hurt the victim) or infancy (offender is a small child). We might say the accused has committed no crime, or they have committed a crime, but we forgive or excuse it in this situation.

Insanity is an excuse defense because an unjustified wrongful act occurred, but the person cannot be held responsible due to the circumstances. For example, the accused person killed a victim they believed (incorrectly, due to a delusion) was attacking them. In fact, the victim was an innocent bystander on the sidewalk.

6.3.2 Formulations of the Insanity Defense

The idea of the insanity defense has long existed in the criminal common law, stemming from the basic notion that people should not be held criminally responsible for unintended actions or for events that they could not control. The Constitution demands that a person be competent to stand trial (under Dusky) and that right is carefully guarded. However, there is no similarly protected “right” to assert an insanity defense. A few states (Kansas, Idaho, Alaska, Utah, and Montana) have largely rejected the use of an insanity defense, and this has been found not to violate the Constitution. Kahler v. Kansas, 598 U.S. __ (2020). Most states do recognize the insanity defense in one of four basic formulations described in this section.

6.3.2.1 The M’Naghten Rule

The first enduring version of the insanity defense originated in the mid-1800s in England. This version of the defense was a reaction to a high-profile case involving a man named Daniel M’Naghten. M’Naghten had murdered a man named Edward Drummond, the Secretary to the Prime Minister of England. M’Naghten killed Drummond, believing that Drummond was actually the Prime Minister, and, under the influence of a paranoid delusional belief, that the Prime Minister was out to kill M’Naghten. M’Naghten was found not guilty and sent to a hospital under the common law approach to insanity at the time. However, many were upset by his acquittal, and as a result, a stricter rule was demanded and created: the M’Naghten Rule (Legal Information Institute, 2020).

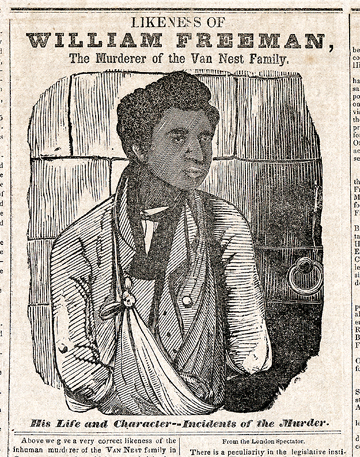

The insanity defense, and with it the M’Naghten rule, came to America just a few years later, in 1847, as part of the case of a Black and Indigenous man named William Freeman (figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2 shows an image of William Freeman in his jail cell in 1847.

Freeman had lived a difficult life, with signs of mental illness and a stint in prison where he sustained a serious head injury from beatings. After his release from prison, Freeman brutally murdered a family – both parents and a toddler. He was defended in court by William Seward, who had been the governor of New York and would later serve as a Senator and Secretary of State under President Lincoln. Despite public hostility towards him for taking on this case, Seward was committed to seeking justice for Freeman. Seward attempted to defend his client based on insanity. The trial court declined to entertain the evidence, however, and found Freeman guilty. Seward appealed Freeman’s case – and with arguments based in part on the recent English M’Naghten case, won him a new trial with the right to present evidence of insanity. Sadly, Freeman died prior to his new trial. The M’Naghten rule, however, survived and became the American legal standard for insanity (Legal Information Institute, 2021).

Under the M’Naghten rule, the defendant is presumed to be sane until they prove to the court or jury that due to a mental disorder at the time of the act, the person fits one or both of these criteria: (1) they do not know the “nature and quality of the act” they are doing, or (2) if they do know what they are doing, they do not know it is wrong.

For example, a person who is significantly developmentally and intellectually disabled kills a victim, but due to the influence of their mental disorders they believe they have helpfully assisted the victim to go to sleep, with poison. This scenario might support an insanity defense under the first M’Naghten prong. Alternatively, the person has killed the victim, and they do know they did that, but they thought (due to a delusional disorder) they had to kill the victim to protect their children from certain death at the hands of the (actually innocent) victim. This second scenario might warrant a defense under M’Naghten’s second prong.

The M’Naghten rule is not perfect, and some of the later-developed versions attempt to improve upon it. However, the M’Naghten rule became the standard definition for insanity in the United States, and it remains so in about half of the U.S. States and the federal courts (Legal Information Institute, 2020).

6.3.2.2 The Irresistible Impulse Test

Under the Irresistible Impulse test, an accused person argues that a mental disorder prevented them from controlling their behavior or compelled them to do the bad act: they were unable to stop themselves. Therefore, they lack criminal responsibility for what is essentially an event outside their control. While the M’Naghten rule focuses on the accused person’s mental state, the Irresistible Impulse approach considers the person’s volition, or choice. Even where a person does understand their wrongful conduct, which would make them ineligible under M’Naghten, the Irresistible Impulse test asks whether the person was capable of controlling their choice to do the act, given the impact of their mental disorder.

The Irresistible Impulse test is not so much a stand-alone legal standard as it is an addition to the M’Naghten rule, seeking to fill a perceived gap in coverage by M’Naghten. Many consider this test to be too broad, risking that a person with mere low self-control (rather than, say, a person with severe mania who is unable to control their conduct) could use the defense and avoid accountability (Legal Information Institute, 2020). Indeed, much criminal conduct is committed on “impulse,” so the difficult question is whether that impulse was, truly, “irresistible.”

Given its limitations, the Irresistible Impulse test is infrequently used, making only occasional appearances since it was first created by an Alabama court in the late 1800s. Parsons v. State (1887). One sensational example of the Irresistible Impulse defense was discussed earlier in this text in the Spotlight on Lorena Bobbitt (Chapter 2). Lorena cut off her then-husband’s penis and disposed of it alongside a road in 1993, resulting in a riveting multi-year international news cycle. Bobbitt was not convicted of any crime for this act, however, because the jury in her trial found that she had acted under the force of an irresistible impulse – she “snapped” due to the impact of being raped by her husband, while experiencing multiple mental disorders (depression, post-traumatic stress disorder) that, themselves, would not have excused her conduct.

6.3.2.3 The Durham Rule

Under the Durham rule of insanity, an accused person is not criminally responsible if their wrong act was the “product” of a mental disorder. This “product” approach has been followed in New Hampshire since the late 1800s, but it got its name from a federal court case that used the same idea: Durham v. United States (1954). The rule seems appealing in its simplicity, but it is not widely used and currently remains the law only in New Hampshire.

The Durham rule is so broad that it would seem to cover everything under the two previously discussed rules – M’Naghten and Irresistible Impulse – and more. It does not sit well with many observers that under the Durham rule, a person might understand what they are doing, know it is wrong, and be able to control their actions — yet still be excused from criminal responsibility upon the conclusion of a mental health provider that the person’s actions were otherwise a “product” of a mental disorder (Legal Information Institute, 2020). For example, the defense in this form could be used, in theory, by a drug user who blames criminal conduct on a substance use disorder – an outcome that would not appeal to the general public. According to critics, the Durham rule is also too dependent on the conclusions of mental health professionals — which can vary greatly person to person (FindLaw, 2019). the-durham-rule.html

6.3.2.4 The Model Penal Code Rule

Many states, including Oregon, have adopted large portions of their criminal law from the Model Penal Code (MPC). The MPC is a criminal code created by the American Law Institute (ALI), a group of legal experts, in 1972. The MPC was developed in order to provide state lawmakers with standard language on which to base their statutes. The MPC included a version of the insanity defense that is similar to the M’Naghten Rule, with a touch of Irresistible Impulse. This MPC version (MPC Section 4.01) provides that a person is not responsible for criminal conduct where, as a result of a “mental disease or defect,” they lack “substantial capacity” to either:

- “appreciate” the criminality of the conduct, or

- “conform” their conduct to the requirements of the law.

The MPC thus allows the insanity defense to be used where a person did not understand what they were doing, or did not know that it was wrong, or was unable to stop their wrongful behavior (Legal Information Institute, 2020).

About twenty states use a Model Penal Code version of the insanity defense (just a few short of the number that use a variation on the M’Naghten rule; FindLaw, 2019b). The federal courts had initially adopted the Model Penal Code version, as well. However, federal law was amended to restrict use of the insanity defense in the 1980s. Public outcry demanded the defense be more restrictive after the acquittal of John Hinckley, who had shot then-President Ronald Reagan in an attempt to impress actress Jodie Foster. The Hinckley case is discussed in more detail in the Spotlight in this chapter.

Oregon’s affirmative defense of insanity tracks the language of the Model Penal Code but is entitled “guilty except for insanity,” more commonly known as GEI. ORS 161.295, 161.305. Happily, Oregon in recent years rejected the outdated and offensive Model Penal Code language of “mental disease or defect” and substituted “qualifying mental disorder” as the precedent for a GEI verdict. ORS 161.295(1). In Oregon, and elsewhere, a mental disorder is excluded from the defense if the disorder consists solely of repeated criminal or antisocial conduct. This exclusion ensures that diagnoses such as pedophilia or antisocial personality do not excuse criminal conduct. ORS 161.295(2). See Chapter 2 for more discussion of specific disorders.

6.3.3 SPOTLIGHT: John Hinkley, Jr. and the Insanity Defense

John Hinckley, Jr. was raised in a home not unlike that of many conservative American families. His father worked full time, and his mother stayed home to care for her son and keep up the house. Hinckley was emotionally dependant upon his mother throughout his adolescence, but none would ever have guessed that he would someday become notorious for an attempted presidential assassination.

The first signs of trouble came in the late 70s when Hinckley first viewed the movie Taxi Driver. What began as a simple affinity for the film later became an all-consuming obsession. He adopted the dress, mannerisms, and lifestyle of the main character, and developed a burning desire for the actress, Jodie Foster, who depicted a teen prostitute in the film.

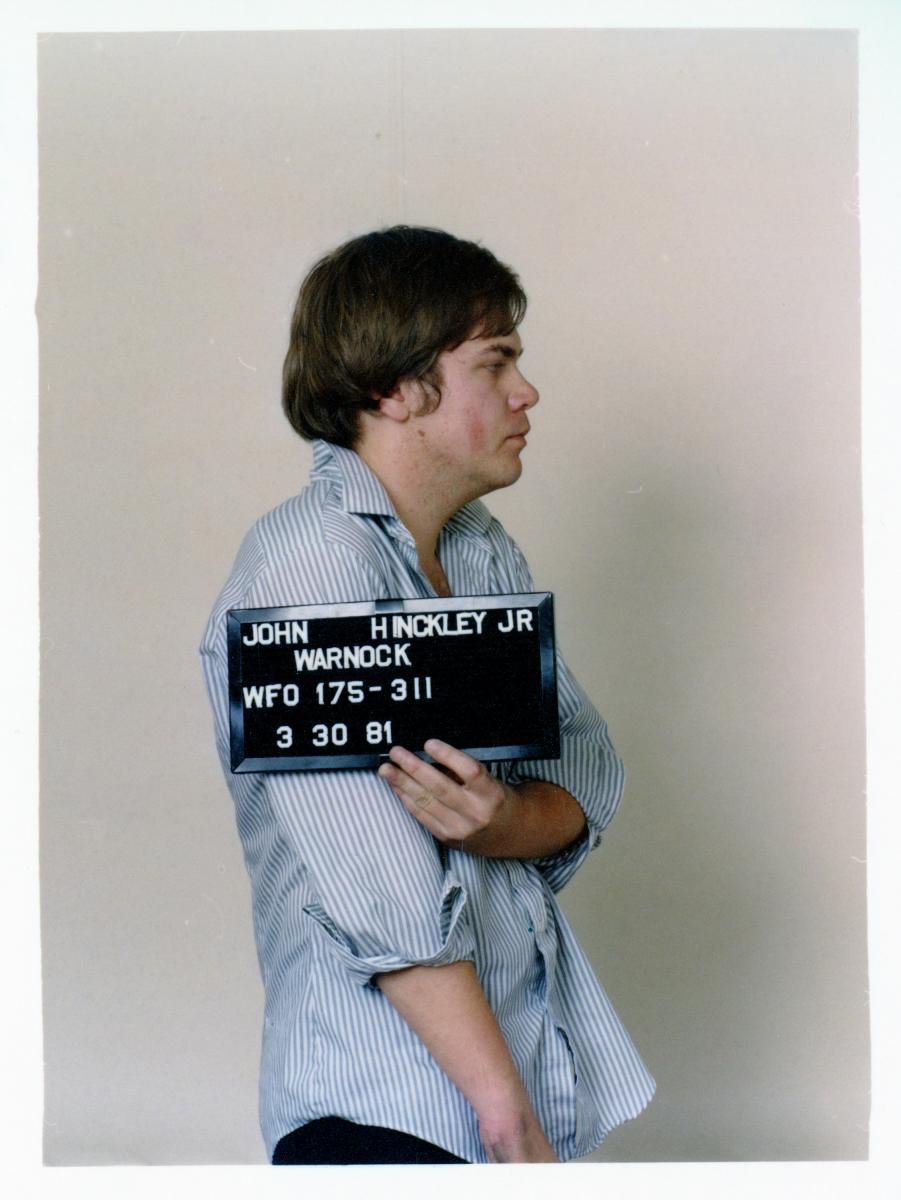

This obsession manifested itself outwardly in the form of stalking. As his mental health deteriorated, and Jodie Foster remained unimpressed by his attempts to get her attention, Hinckley came to the conclusion that he needed to assassinate the President of the United States. By the time he acted on this decision, Ronald Reagan was the sitting President. Hinckley made his attempt on March 29, 1981, and was promptly taken into custody (figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3. John Hinckley, Jr. ‘s 1981 mugshot, holding identifying sign.

John Hinckley was put on trial in 1982, and many Americans were outraged when he was found not guilty by reason of insanity. ABC News conducted a poll the day after the verdict was read, and it showed that 83% of the respondents believed “justice was not done” and Hinckley should have been found guilty of a crime. This public pressure spurred Congress—and many individual states—to enact major reforms. In fact, eighty percent of the insanity reforms that happened over the next decade can be attributed to the outcry over the Hinckley verdict (Collins, Hinkebein, & Schorgl, 2022). All of the reforms focused on limiting a defendant’s ability to use the insanity defense in a criminal trial.

As for John Hickley, he was transferred to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington. He was released back into the community in July, 2016 after 41 years hospitalized under the supervision of mental health professionals.

Resources:

Collins, K., Hinkebein, G., Schorgl, S. (2022). The Hinckley Trial’s Effect on the Insanity Defense. Retrieved from https://famous-trials.com/johnhinckley/540-insanity.

Linder, D. (2008). The Trial of John W. Hinckley, Jr. Retrieved from http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hinckley/hinckleyaccount.html.

Linder, D. (2022). John Hinckley, Jr. Trial (1982). Retrieved from https://famous-trials.com/johnhinckley.

6.3.4 Licenses and Attributions for Insanity as a Criminal Defense

“The Insanity Defense” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“SPOTLIGHT: John Hinckley and the Insanity Defense” by Monica McKirdy is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.2. is an image of William Freeman in his jail cell in 1847. Originally from the Rochester Daily Advertiser, http://www.rickgrunder.com/sold.htm, in the public domain.

Figure 6.3. Photo of John Hinckley from https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/public/archives/photographs/jhjphotos/jhj-206.jpg is in the public domain.