9.2 Fundamentals of Civil Commitment

Imagine a person who has a serious mental illness; this person lives with family in the community, where they receive treatment and support. The person decides to stop taking prescribed medications and their symptoms escalate. Perhaps they begin hearing voices, and the voices direct them to start fires; they have thus far resisted the commands, but they find them compelling. Or, maybe the person has severe depression and their current presentation is similar to that which preceded an earlier suicide attempt, causing grave concern for their safety. The person refuses treatment, but their condition is deteriorating. In these circumstances, or many other scenarios we might imagine, the question is the same: how do we keep this person and those around them safe, while respecting the person’s rights to freedom and autonomy?

Civil commitment provides a way for the legal system to respond to this person who has become unsafe, to self or others, due to a mental disorder. Initiation of the civil commitment process allows a person to be taken to a hospital for intervention, and a completed civil commitment allows a judge to order the person to receive treatment for their mental disorder. A civil commitment order can, but does not always, require psychiatric hospitalization.

A civil commitment does not involve punishing a person for doing something wrong (which makes it different from a criminal case) but it does involve supervising a person and limiting their freedom—even potentially confining them (which is, in some ways, like a criminal case). Because civil commitment is a significant infringement on the freedom of a person who has done nothing wrong or criminal, it is important to be extremely cautious in its use. There are processes and procedures laid out in every state’s civil commitment laws to ensure that commitment is used properly and that the person’s rights to freedom and autonomy are protected.

9.2.1 Civil Commitment Process

Though all states have involuntary commitment processes, civil commitments are fairly unusual. After a long history of forced confinement and mistreatment, people with mental disorders today are now almost always treated on a voluntary basis—even when they have serious mental illness or disability. In 2015, it was estimated that only about 9 out of every 1000 people with serious mental illness were involuntarily committed (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019).

More commitments are initiated than are actually completed. Some people who find themselves facing civil commitment proceedings end up consenting to voluntary services, preferring that to being ordered into care (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). Many others are found inappropriate for commitment at some time during the process, for example if they do not present a danger to themselves or the community. Additionally, though it would be difficult to quantify exactly how often this occurs, commitment is not even attempted for a great number of people who do need care. Reluctance to initiate civil commitment proceedings is often based on two accurate perceptions about the process: that commitment is very difficult to obtain and that there are few resources to treat these patients.

The civil commitment process differs from state to state – and sometimes even county to county within a state – because each jurisdiction has its own involuntary commitment laws with unique language and procedures. Prior to the 1960s, when most civil commitment laws were developed, people with mental disorders tended to be confined or segregated as a matter of course, rather than based on strict legal standards. So, it is important to note that civil commitment laws evolved as a protective limitation on the practice of forcing people with mental disorders into treatment and institutions (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019).

Some states, including Oregon, have separate but parallel commitment statutes, one addressing people with mental illness (Oregon Revised Statutes, Chapter 426) and another for people with intellectual or developmental disability (Oregon Revised Statutes, Chapter 427). These laws have differing specifics suited to the protection of the populations addressed. References to Oregon law in this chapter are mainly concerning civil commitment due to mental illness under Chapter 426.

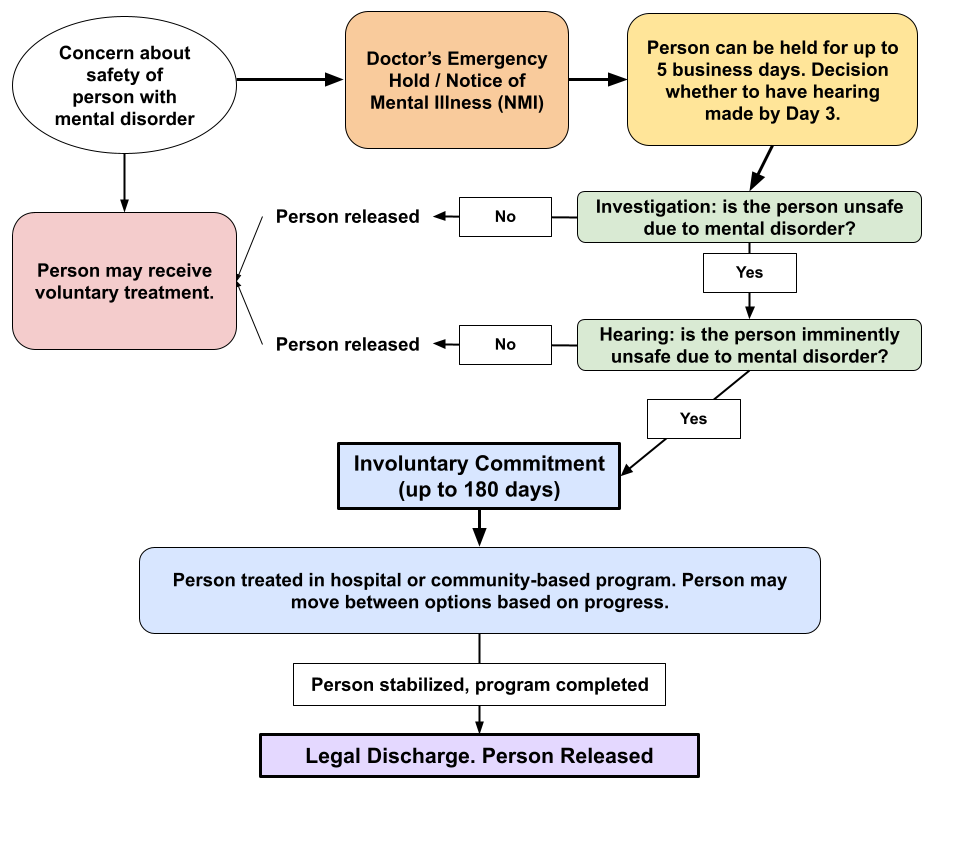

The flowchart in figure 9.1 shows the progression of the civil commitment process in Multnomah County, Oregon, as just one example of these procedures. The flowchart shows the general progression of the commitment process. As you can see, the process is triggered by a concern about safety due to mental disorder, then proceeds to a hold, an investigation, a hearing, and ultimately – maybe – an involuntary commitment. The proceedings can terminate at several points prior to a finalized commitment. Each part of the process shown in the flowchart is discussed in more detail in this section.

Figure 9.1: This flowchart shows the progression of the civil commitment process, based on the process used in Multnomah County, Oregon. Other states’ procedures may vary in specifics but follow the same general trajectory.

9.2.2 Initiating Commitment

The civil commitment process often starts with an emergency hold, which allows a doctor to order that a person be kept under medical supervision. This type of restriction may also be called a hospital hold (OAR 309-033-0210 (19)). The hold keeps a person safe while providing time for their mental health to be assessed and for involuntary commitment proceedings to be considered.

Often, however, a preliminary step is getting the person to a doctor who can assess the person’s mental health. If a person is unwilling to go voluntarily, the law generally allows the person to be picked up by police (taken into custody) and transported to a hospital. This type of police custody is authorized for the limited purpose and only the amount of time necessary to get the person to a hospital. Custody must be based on reliable information that the person needs to be controlled for safety reasons—that is, they are believed to have a mental disorder and they are dangerous to others or themselves.

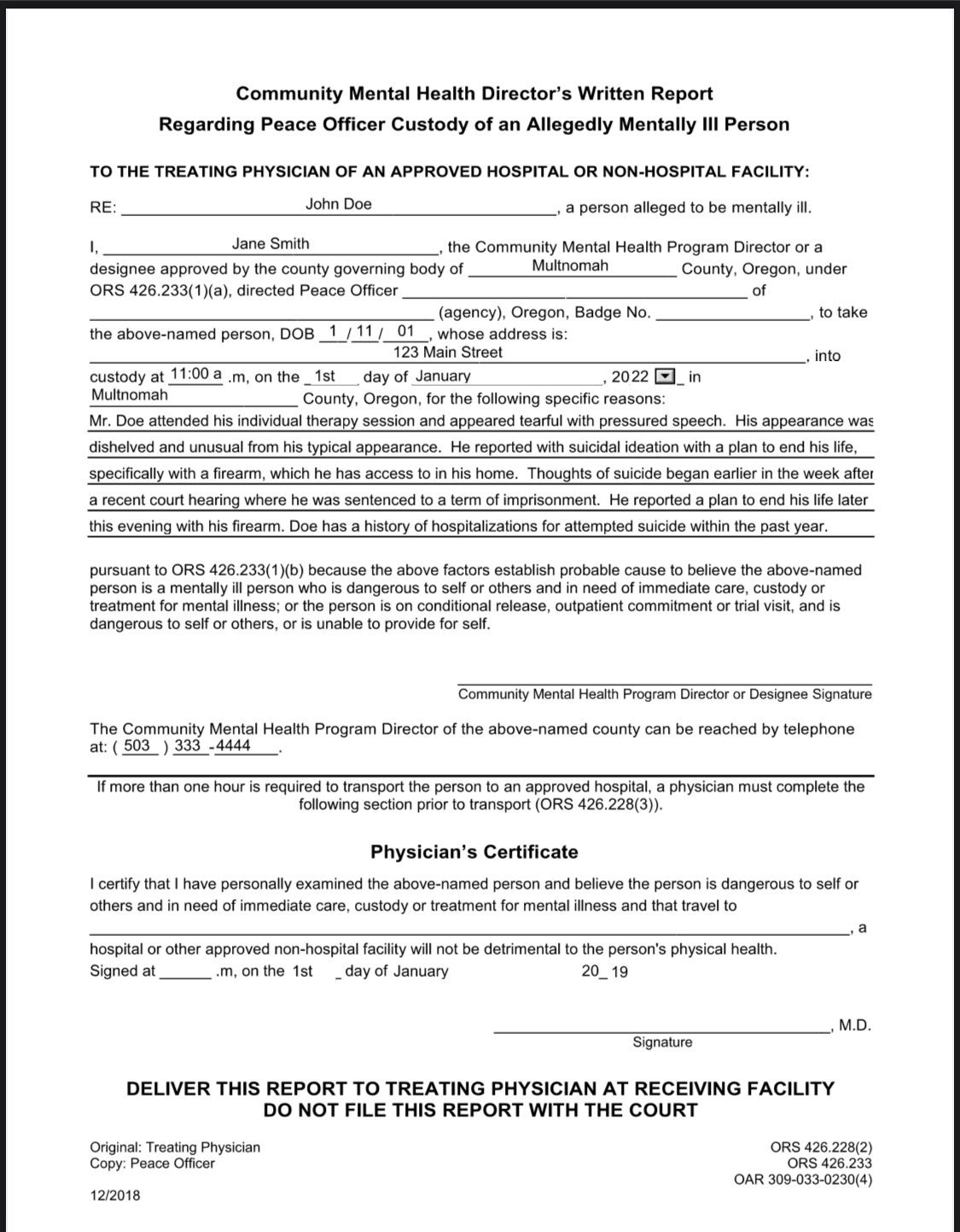

Custody can be initiated in various ways, and is regulated by state law. In Oregon, under Chapter 426, every county has a mental health director who designates qualified mental health professionals with the power to approve hospital transport (figure 9.2). Police can also take a person into custody and to a hospital on their own authority as peace officers. See the Spotlight on Initiating Civil Commitment for an example of a form used in Oregon to start the process of a hold.

9.2.3 SPOTLIGHT: Initiating Civil Commitment in Oregon

This form (figure 9.2) shows an example of an Oregon community mental health director’s authorization to take a person into custody for emergency mental health care. Note the specific details about immediate danger that are included in this example form.

Once a hold is initiated, its length is limited by state law. Most commonly, states permit involuntary admission to a hospital for just a few days before a judge must review the matter to ensure the medical hold is legally justified. In Oregon, for example, as shown in the flowchart in figure 9.1, a person may be held up to five business days on a doctor’s order, or hospital hold, before the case must be reviewed by a judge.

A medical hold is only one route to initiating civil commitment. Most states allow any person, following certain rules and procedures, to initiate the process of civil commitment via paperwork submitted to a court. In Oregon, the law allows certain designated officials, or any two people acting together (such as family or friends of the person), to initiate the commitment process. This type of request for civil commitment is usually called a public petition for civil commitment (OAR 309-033-0240 (1)(a)).

Regardless of how the civil commitment is initiated, the paperwork submitted to a court is what starts the legal process of civilly committing a person. In Oregon, the official paperwork submitted to a court is called a Notice of Mental Illness (NMI). The NMI is what triggers the court’s involvement in a legal commitment.

The next steps in the commitment process are a pre-commitment investigation and a civil commitment hearing. A pre-commitment investigation includes an evaluation by mental health professionals to determine what, if any, mental disorder the person is experiencing, and how that mental disorder is currently impacting the person facing commitment. Designated investigators, usually state or county mental health professionals, gather evidence that will be presented in a later commitment hearing. Investigators may speak with family members or other witnesses. The investigation is intended to establish whether the person’s current circumstances warrant civil commitment: does the person have a mental disorder, and does that mental disorder make them dangerous? The question of “dangerousness” is central to the court’s ability to commit a person, and it is not an easy question to answer. Dangerousness is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

9.2.4 Diversion from Commitment

Even where first steps toward civil commitment have been taken—a hospital hold is in place, or a petition has been filed, or a hearing has commenced—the person may not ultimately be committed. A pre-commitment investigation, or simply time, may reveal that the person is safe, or that the person does not have a mental disorder warranting commitment (e.g., they were intoxicated, not mentally ill).

Alternatively, during the pre-commitment period a person may be “diverted” into voluntary treatment—avoiding involuntary commitment by consenting to necessary care. Diversion in this context is used in the same sense that this text has previously (in Chapter 4) discussed criminal diversions: diversion allows a person to access services without the burden and/or stigma of a formal system determination against them. In other words, a person can get the benefit of treatment without a judge having to decide they are dangerous. Oregon law encourages diverting civil commitment subjects into voluntary intensive treatment for a 14-day period rather than finalizing commitment, where possible (ORS 426.237(1)(b)).

Diversion to voluntary treatment may be preferred over involuntary commitment for many reasons. Voluntary treatment is potentially more effective and less expensive than commitment. Voluntary treatment may be more available; in many states, there is a critical shortage of beds and facilities for people who are committed involuntarily. It may also be more attractive to the impacted person than a lengthy and restrictive commitment, which can last for many months.

Finally, though civil commitment does not create a criminal record, it does create a record with consequences. A person who has been civilly committed will face limitations on their right to possess firearms (18 USC Sec. 922(d)(4)). They may also be more readily committed in the future, should similar circumstances arise. Oregon law, for example, provides a special pathway for commitment where a person has two previous commitments and is exhibiting the same symptoms that preceded the earlier commitments (ORS 426.005(1)(f)(C)(i-iv)). A person who engages in voluntary treatment, even in a last-minute diversion from commitment, does not face these consequences.

9.2.5 Commitment Hearing & Outcome

If a person who is the subject of commitment proceedings is not diverted into voluntary treatment or otherwise released from the process, the next step is a commitment hearing. The commitment hearing usually occurs fairly quickly—ideally in a matter of days from the initial hold.

A judge or hearings officer presides over the hearing to consider the evidence and decide whether to order the civil commitment. The person facing commitment will have an attorney to represent them, so they may oppose the commitment, and the state is represented by an attorney who advocates in favor of commitment. Witnesses, including pre-commitment investigators and mental health evaluators, will be allowed to testify and/or submit reports, and attorneys can ask them questions.

The evidence and questions at the hearing are directed to the issues of whether the person is:

- affected by a mental disorder, and

- whether they are currently dangerous or gravely disabled.

The presence of a mental disorder is, usually, not the primary issue; professional evaluators will offer expert opinions as to whether a person has mental illness, or the person may well agree that they have a mental illness. The second question, whether the person is a danger to themselves or others, is the much more difficult and contentious question. The way that the particular state or its courts define “dangerous” will be critical to the court’s decision on this issue, and of course, states define this term in varying ways. In order for commitment to be ordered, a person’s risk has to fit within the definition of “dangerous” in that particular state.

Typically, “dangerous” has its commonly understood meaning—likely to cause harm— so that a person who is making serious threats against themselves or another person, or who seems poised to hurt themselves or another, may be deemed “dangerous.” Courts have also interpreted “dangerous” to mean immediately or imminently dangerous – meaning dangerous now, not in the future.

Many states also have a commitment category for “grave disability.” Grave disability is a specialized term which usually means that the person is unable to provide for their basic needs (food, shelter) such that they will experience harm in the very short term. For example, a person experiencing delusions or paranoia about food may be unable to eat. If the person develops malnutrition due to these symptoms of their mental illness, they may be considered gravely disabled by their mental illness. Some states have a “grave disability” standard for commitment without using those precise words. Oregon, for example, allows commitment of a person who is “unable to provide for basic personal needs” (ORS 426.005(1)(f)(B); Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019).

If, at the conclusion of a commitment hearing, the judge does find that, due to mental illness, the person is immediately dangerous or gravely disabled, as required by state law, then the judge will order an involuntary commitment. A commitment usually lasts for several months, but it can be shortened if the person regains stability warranting early discharge. The maximum time for a commitment in Oregon is 180 days, after which another hearing is required to continue involuntary treatment. This time period is fairly typical among state laws.

The care provided to a person via civil commitment may include hospitalization or an outpatient treatment program. In some circumstances, and with additional procedures, psychiatric medications can be required for the committed person. Medicating a person on an involuntary basis requires a showing of “good cause,” meaning the medication is necessary to deal with an emergency situation, or proof that the person does not have capacity to make a reasonable decision about taking medication, so medical providers must make the decision for the person. In Oregon, involuntary medication is a multi-step process with at least two doctors involved, and there is a separate opportunity for legal review as well (Yost et al., 2012).

As shown in the flowchart in figure 9.1, Oregon provides opportunities for a person to improve and progress, even while they are civilly committed. The person may start treatment in a hospital setting and progress to a less restrictive community setting. If a person makes significant progress and no longer meets criteria for commitment, the person can also be transitioned to “voluntary” status—in which case they can make a choice to leave the hospital (ORS 426.300). Most states have similar, though not identical, options for resolving commitments.

9.2.6 Licenses and Attributions for Fundamentals of Civil Commitment

“Fundamentals of Civil Commitment” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.1. Flowchart of Civil Commitment in Oregon by C. Courtney, H. Courtney and Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adapted from Multnomah County Commitment Services. ].

“SPOTLIGHT: Initiating Civil Commitment in Oregon” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.2. Community Mental Health Director’s Hold Form by Oregon.gov is included under fair use. Form filled out by Kendra Harding.