4.4 Sequential Intercept Model

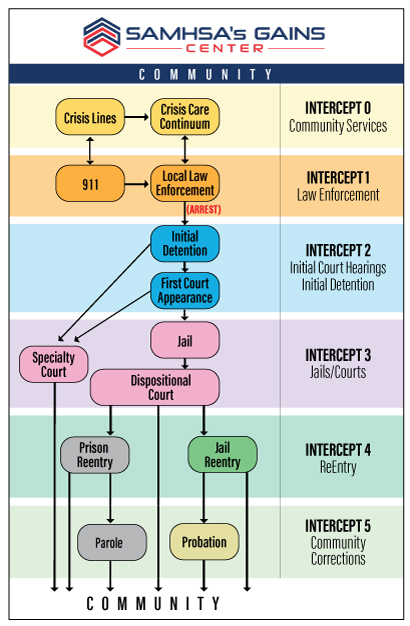

Diversion timing and opportunities are illustrated in the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM). The SIM is a valuable tool for discussing and assessing various diversion options that may be available in, or missing from, a community (figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7 is SAMHSA’s diagram of the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM). SAMHSA’s website provides a detailed description of the SIM and specifics about each Intercept, numbered zero to five. Intercept zero depicts community resources that precede entry into the criminal justice system. Intercepts one through five depict points in time that are progressively further along in the criminal justice progression. On the left side of the diagram are examples of diversion opportunities that occur at each designated intercept.

The SIM illustrates how exit from the criminal justice system can occur at several points in time, from beginning to end of a typical pathway through that system. Each intercept within the SIM represents a window in time during a person’s interaction with the criminal justice system where that person might be provided with direction or opportunity (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2022).

The SIM helps us visualize and consider each window in time where intervention and diversion might occur as a person proceeds through the criminal justice system. The specific diversion opportunities that may be available at each juncture are dependent upon the needs of the individual at that time, as well as the desires and resources of the community. Every community can look at the SIM and consider these important questions:

- Do we have diversion opportunities present at intercepts we consider most valuable?

- What opportunities or resources are missing?

- Where we lack diversion opportunities, can those be added or can others be shifted to maximize impact?

Because diversion involves cooperation from different agencies and groups who play roles in the process, creating opportunities requires input from an array of professionals, including first responders, mental health workers, and criminal justice professionals (Oregon Center on Behavioral Health and Justice Integration, 2022).

Each intercept in the SIM is briefly described below, with a link to the corresponding intercept discussion on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website, which provides more information and examples of programs at each intercept point. SAMHSA is an agency of the U.S. government that leads public health initiatives aimed at improving national mental health, and it offers excellent resources and information on mental illness and substance use disorders.[1]

4.4.1 Community Services (Intercept 0)

The very first intercept point, Intercept 0, is arguably the only opportunity in the SIM for true diversion out of the criminal justice system, in the sense of avoiding it entirely. This intercept was added to the model in 2017, several years after the SIM was initially developed, and it focuses on the first recognized need for service or point where a crisis is identified (Pinals & Felthous, 2017). Intercept 0 suggests responses that eliminate the need for police presence, never opening the door to the criminal justice system or the enormous risks that police encounters present for those with mental disorders. Community service responses, such as hotlines, crisis lines, or other non-police response systems are all encompassed in Intercept 0.

One exciting Intercept 0 option are response teams, considered police alternatives, that are increasingly being developed in cities throughout the country, often modeled after Eugene, Oregon’s early and successful CAHOOTS program, discussed further in Chapter 5 (Turner, 2022).

4.4.2 Law Enforcement (Intercept 1)

Before Intercept 0 was added to the SIM, Intercept 1 was the first imagined opportunity for diversion out of the criminal justice system. (See Using the Sequential Intercept Model to Guide Local Reform). Intercept 1, Law Enforcement, focuses on policing as a tool that can be used for far more than just arresting people. Intercept 1 imagines police serving as a filter of sorts: arresting people who need to be taken into criminal custody, while performing a protective or supportive role for others who may have been referred to or otherwise come to the attention of law enforcement but will not be best served by arrest. Of course, police have always had discretion to operate in this manner, but Intercept 1 spotlights this opportunity and encourages skilled and informed approaches by law enforcement. And, use of this discretion and skill to keep police interactions non-violent is critical for the safety of people who experience mental disorders. According to the Treatment Advocacy Center, approximately 1 in 4 people killed by police have serious mental illness (SMI). This appears to give people experiencing SMI a 16 times greater chance of death in these encounters than people without SMI.

One of the most prominent examples of Intercept 1, discussed in more depth in Chapter 5, is the training of law enforcement responders to de-escalate mental health crisis situations without unnecessary use of violence and coercion. Programs to accomplish this type of training have been developed over the past several decades and some police departments, such as Portland Police Bureau, now require all officers to complete a 40-hour crisis response training specifically targeted to interactions with people with mental disorders. A step further, co-response teams, where law enforcement officers are accompanied by trained mental health professionals, who together respond to and manage calls involving mental health crises, are an increasingly favored Intercept 1 approach. Both approaches, law enforcement training and co-response teams, are discussed further in Chapter 5.

4.4.3 Initial Detention and Initial Court Hearings (Intercept 2)

Intercept 2, Initial Detention / Initial Court Hearings, is focused on diversion opportunities for people who have been arrested and are facing initial criminal court appearances. Here, the emphasis is on screenings or evaluations to identify the presence of mental disorders and substance use disorders, as well as efforts to avoid or minimize time in custody, where possible. For example, community-located treatment and supervision can be a successful substitute for holding a person in custody prior to resolution of charges, allowing a person to avoid the negative impacts of jail, while benefiting from substance use treatment or other appropriate services.

Pretrial services in both the federal and state court systems would be considered an Intercept 2 diversion, as these programs allow a person to be supervised in the community while awaiting trial. Generally, the person charged with a crime appears before the court for their initial appearance. If the court agrees that the person is suitable for community supervision (for example, not likely to disappear or present a danger) they would be released with certain conditions to follow. A pretrial officer would be charged with supervising the person as they move through the court process. The person is not convicted of any offense at this stage, so it is still possible that charges could be dismissed in a resolution of the case.

4.4.4 Jails and Courts (Intercept 3)

As focus shifts to Intercept 3, Jails and Courts, the SIM highlights diversion opportunities for people who are being held in custody facing charges for offenses. A common criticism of diversion at this Intercept is that defendants may be required to admit guilt and face conviction or punishment should the diversion not succeed. Here, the threat of criminal justice consequences is used as leverage to ensure the participant’s cooperation in the diversion process. In other words, a person who has been required to admit to wrongdoing in order to qualify for diversion may be motivated by fear of conviction or incarceration if they do not follow through with the diversion program. Does this help in the end? Some observers may applaud this approach and consider it an opportunity for defendants that also prioritizes public safety. Others may argue that this type of leverage, or threat, is an inappropriate way to ensure treatment engagement when “forced” treatment is less likely to ultimately succeed.

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, most diversions are imperfect, and most could be improved in some respects by simply happening earlier, thereby avoiding interactions with law enforcement, avoiding incarceration, and/or avoiding creation of a criminal record with the impact on life opportunities that entails. This article from the Prison Policy Initiative uses a non-SIM “highway” model to discuss diversion opportunities, and develops the argument in favor of earlier diversions to maximize participant choice while minimizing criminal justice engagement.

One popular Intercept 3 option is the mental health court. Mental health courts, modeled after other problem-solving courts (e.g., drug courts) focus on treatment of a problem, rather than punishment of an individual, as a response to offending conduct. These problem-solving courts follow the long-time example of juvenile courts in considering not just what a person did, but why a person behaved in a particular way, using the court system to support sustainable behavior changes, rather than incarceration and eventual return to offending.[2]

Like typical courts, mental health courts are overseen by a judge, the person charged is represented by an attorney, and there is a prosecutor representing the state. The focus is on case management, connecting the charged person with community support, job opportunities, and treatment – all supervised by the court. A person may be given the opportunity to participate in mental health court when they have an identified mental disorder, and, generally when they have been charged with a non-violent offense appropriate to this more informal approach.

As noted earlier in this chapter, some advocates dislike later-stage diversions such as mental health courts, voicing concern that these criminal-justice-involved efforts detract from more proactive community mental health initiatives (Berstein & Seltzer, 2003). Like all diversions, mental health courts have flaws, and one concern around this diversion approach is that it may actually encourage arrest and criminal justice system involvement by providing support in that context, where these supports may be harder to access outside of the system.

Watch the 13-minute video in figure 4.8 and consider the pros and cons of mental health courts, as well as other later-stage diversions. Ask yourself these questions:

- Are the potential benefits to the person and their community worth the risk of the deeper engagement in the criminal justice court system?

- Do you agree with the Minnesota judge in this video, who believes that mental health court offers a better alternative to a revolving door to prison? As the judge points out, a person will often leave prison and commit the same crimes, while a person going through mental health court is actually taught to be in the community.

Figure 4.8. A rare look inside a mental health court [YouTube Video]. This video provides a rare look inside a mental health court, where we hear from all the participants.

4.4.5 Reentry (Intercept 4) and Community Corrections (Intercept 5)

The later intercepts modeled in the SIM, Intercept 4 (Reentry) and Intercept 5 (Community Corrections) are more focused on community success after a person has moved through the criminal justice system. In these final opportunities for diversion, a person is not so much avoiding criminal justice involvement and consequences (as those have already occurred) but seeking to lessen the fallout of their justice system involvement, including the likelihood of recidivism, or reoffending, related to mental health and leading to return to the criminal justice system. This is no small task, as overall, offenders released from state prisons are found to reoffend at a rate of 83% within nine years of release (Alper et al., 2018).

At Intercept 4, the SIM is focused on reentry, where a person is leaving jail or prison and reentering the community, often under probation or parole supervision. Efforts to create success in reentry should begin during incarceration and continue in the community, as discussed further in Chapter 7 and Chapter 8. Diversion efforts at Intercept 4 may appear as arrangements to meet mental health, medical, or other basic needs as part of reentry planning. Without needed medications or other treatment in the community, people with mental disorders are more likely to engage in new offending behavior and find themselves, once again, winding through the criminal justice system (Weatherburn et al., 2021).

Intercept 5 focuses on community corrections, which refers to a period of oversight outside of jail or prison (probation), or after serving time in jail (parole). A person under this type of supervision will have particular conditions they must fulfill in order to remain in the community, and they can be sanctioned by the court or a supervising agency, potentially landing the person right back in custody.

One important aspect of any diversion at Intercept 5 is ensuring that supervising authorities are well-trained and attuned to mental health needs and disabilities. For example, probation officers may carry specialized caseloads of clients with identified mental health needs, and be highly focused on supportive collaboration with partner agencies and community organizations that may contribute to the success of community supervisees.

As one example of an Intercept 5 effort, the Multnomah County, Oregon, Mental Health Unit (MHU) provides supervision services for people with severe and persistent mental illness who are on parole, probation, and in post-prison status. The MHU partners with various state and community agencies and organizations that support and treat this population, including treatment providers, law enforcement, defense attorneys, the courts, and advocacy groups like NAMI. The goal of the MHU is to increase community safety, while reducing criminal recidivism and mental health relapse.

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT), or the use of FDA-approved medications to treat substance use disorders, in both jail and community settings, is a critical Intercept 4-5 intervention that has been shown to reduce enormous risks of relapse and overdose in people dependent on opioids and alcohol, particularly in the face of the ongoing opioid crisis.

4.4.6 Licenses and Attributions for Sequential Intercept Model

“Sequential Intercept Model” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.7. SAMHSA’s Gains Center diagram of the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) is in the public domain.

Figure 4.8. Video: A Rare Look Inside a Mental Health Court, Blue Forest Films – You tube license attribution

- The SIM was developed by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) GAINS Center for Behavioral Health and Justice Transformation. The GAINS Center is a government effort aimed at increasing community resources for justice-involved individuals via support and training for mental health professionals and organizations at all levels of government. The SAMHSA/GAINS goal to “transform the criminal justice and behavioral health systems” recognizes and seeks to reduce the problem of criminalization of mental disorders (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2022). ↵

- There are thirteen mental health courts in the State of Oregon including the Multnomah County Mental Health Court in Portland, led by Circuit Court Judge Nan Waller (Multnomah County District Attorney, 2022). ↵