9.3 Limitations on Civil Commitment

Over time, our society has come to recognize that people with mental disorders—like other people—enjoy individual rights and personal liberties. People do not automatically forfeit their rights to freedom and autonomy when they experience illness or disability. Rather, rights must be compromised only in extreme circumstances, for important reasons, and with adequate protections in place.

As you will recall from the history of mental disorders and the development of laws related to mental disorders in Chapter 1 and Chapter 3 of this text, the existence of rights for people with mental disorders was not always self-evident. The laws related to civil commitment help ensure that people who are experiencing mental illness and disability are not confined or forced into involuntary treatment improperly—merely because of their diagnosis or because they are more vulnerable. Civil commitment has rightfully taken its spot as a “last resort” option in the mental health continuum of care.

9.3.1 Use of Commitment: Safety vs. Freedom

The prospect of commitment raises important questions about the competing goals of safety and individual liberty:

- When is it appropriate to restrict the freedom of a person for something that is merely threatened, but has not yet happened? On the other hand, when is it appropriate to allow a situation to unfold where people may be hurt?

- More specifically to the topic of this text, are we pleased to have a mechanism to help a person avoid engaging in potential criminal activity? Or are we troubled by treating a person, in some ways, like they have committed a crime—when they have not?

Scholars, medical and legal professionals, and disability and mental health communities have struggled with these questions. Opinions differ on how best to strike a balance and identify what takes priority: a person’s need to receive care and treatment for a serious mental disorder that threatens health and safety—or the person’s right to decline treatment and move about the world as desired—even if that desire is influenced or compromised by a mental disorder.

As stated by one prominent scholar considering the issue of civil commitment, “Patients should not die with their rights on. But they should not live with their rights off, either.” (Hoffman, 1) In other words, it is troubling to think of someone sacrificing their life or health for an abstract “right” to liberty, yet it is also troubling to consider that a life preserved via involuntary care may lack the freedom that most of us consider essential to a good life. Do we allow a sick or disabled person to “die with their rights on,” or do we intervene, perhaps maintaining safety and life, but at the expense of freedom, forcing this vulnerable person to “live with their rights off?”

A further challenge in determining the right “balance” between these competing concerns is the impact of inappropriate factors, like racism, sexism, and ableism, on these determinations. For example, studies looking at civil commitment populations have found clear racial bias in involuntary commitment trends: “Patients of color [are] significantly more likely than white patients to be subjected to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, and Black patients and patients who identified as other race or multiracial [are] particularly vulnerable, even after adjustment for confounding variables” (Shea et al., 2022). When freedom and autonomy are generally valued less for a particular group—as has been the case for Black people, women and those with mental disorders in America—the concerns around involuntarily committing members of these groups in their “best interest” should be heightened.

While limits on civil commitment are critically important for protection of those with mental disorders, it is also true that many people involved in the civil commitment process experience legitimate frustration at the seeming unavailability of this tool. Legal and mental health professionals, as well as first responders, may naturally want to prevent harm or stop problems from materializing. A county attorney advocating for civil commitment, for example, has only this route to intervene prior to a person experiencing a severe deterioration in health and safety. If the person comes back to the courthouse as a criminal defendant, after civil commitment was denied, that can be seen as a system failure. If a goal is to avoid criminalizing mental illness, then shouldn’t civil commitment be used more often?

Community and family members may share similar feelings of frustration (or fear, or sadness) as they try to prevent a loved one from becoming very sick, or from acting in ways that might bring them harm or send them into the criminal justice system. Disability advocates may cite the loss of dignity a person may experience due to mental illness before court-recognized imminent danger makes them subject to commitment—and possibly destroys relationships, jobs, support systems, and other critical pieces of a stable life. Should we really allow it to go that far? Should the standard for stepping in with help be lower?

This issue is closely connected to the problem of criminalization discussed in Chapter 4. Ideally, people choose and have access to treatment in the community—but sometimes they can’t effectively access treatment. The criminal justice system can quickly become an alternative source of care, absorbing people who did not qualify for involuntary treatment in a civil process and so become criminally involved: arrested, charged, and confined. As we have learned, vastly more people receive mental health treatment in the criminal system than anywhere else. Objections to this state of affairs range from financial (it’s expensive) to practical (jail is a horrible place to provide mental health care) to ethical (it is simply wrong to criminalize mental disorders). Again, this begs the question: should civil commitment be an easier hurdle? Is the difficulty of obtaining commitment a source of the criminalization problem?

Courts have wrestled with all of these questions, and they face the conundrum of how speedily and confidently to require involuntary treatment for people with mental disorders. Decisions by courts responding to these questions provide us with some Constitutional guidance around civil commitments. However, the issues and questions presented in this section are not easily or finally resolved.

9.3.2 The Requirement of Danger

One of the more important cases that speaks to the issue of civil commitment, and more broadly to the humanity and rights of people with mental disorders, is the case of O’Connor v. Donaldson, decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1975. Kenneth Donaldson (figure 9.3) was committed to the state psychiatric hospital in Florida by his father in 1957. Donaldson was committed based on a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Donaldson stayed in the Florida psychiatric hospital for over 15 years. During this time, Donaldson did not display dangerous behavior, and, it was generally agreed, he received minimal treatment for his mental disorder. During his time in the hospital, Donaldson tried repeatedly but unsuccessfully to be released into the care of friends, who had offered to help him live in the community. O’Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563, at 569.

Finally, Donaldson filed a lawsuit for his release against Florida authorities, including his attending physician at the hospital, Dr. O’Connor. Donaldson based his lawsuit on the federal civil rights statute, 42 USC Sec. 1983. The federal law Donaldson used (referred to as Section 1983) was originally passed as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act. Section 1983 was intended as a way to allow Black southerners to sue state officials (often police) who were violating their federal rights, such as the right to vote. Section 1983 allowed these lawsuits to be heard in federal—rather than state—courts. Federal courts were expected to be more sympathetic to civil rights, and hopefully less overrun by Klan members, than state courts.

Section 1983 in this case allowed Donaldson to assert that the state government (Florida), acting through its employees at the state hospital, had deliberately taken away Donaldson’s federal Constitutional right to liberty. Section 1983, though created in the days of Reconstruction, is still the most important way for a person to challenge a state government official of any type that has violated the person’s federal rights.

Donaldson’s federal lawsuit eventually made its way to the Supreme Court on appeal. In its decision, the Court made landmark statements that signaled a change in how people with mental disorders would be seen with respect to individual freedoms.

Justice Potter Stewart wrote for a unanimous court:

A finding of “mental illness” alone cannot justify a State’s locking a person up against his will and keeping him indefinitely in simple custodial confinement. Assuming that that term can be given a reasonably precise content and that the “mentally ill” can be identified with reasonable accuracy, there is still no constitutional basis for confining such persons involuntarily if they are dangerous to no one and can live safely in freedom.

May the State confine the mentally ill merely to ensure them a living standard superior to that they enjoy in the private community? That the State has a proper interest in providing care and assistance to the unfortunate goes without saying. But the mere presence of mental illness does not disqualify a person from preferring his home to the comforts of an institution.

May the State fence in the harmless mentally ill solely to save its citizens from exposure to those whose ways are different? One might as well ask if the State, to avoid public unease, could incarcerate all who are physically unattractive or socially eccentric. Mere public intolerance or animosity cannot constitutionally justify the deprivation of a person’s physical liberty.

In short, a State cannot constitutionally confine, without more, a nondangerous individual who is capable of surviving safely in freedom by himself or with the help of willing and responsible family members or friends.

O’Connor, 422 U.S. at 576 (internal citations omitted).

It is the last paragraph of the quotation above that is most commonly cited as the “holding,” or ultimate decision, of the O’Connor case. But the preceding paragraphs are significant as well, entertaining arguments in favor of restricting a person like Donaldson – and finding them inadequate. The O’Connor opinion’s grand and somewhat poetic language suggests that the Court recognized the importance of this opinion as it was issued.

The O’Connor Court was, in contrast to all of history, proclaiming that the rights of this vulnerable group of humans could not simply be erased in favor of a desire to “help” them—or due to a preference to avoid them. The Court’s findings acknowledged the condescension and stigma that played such a prominent role in treating people with mental disorders. The Court then clarified that this intolerance does not justify confinement. Rather, there must be something “more,” as the Court said, in order to justify confinement.

Figure 9.3 shows Kenneth Donaldson holding a copy of the Supreme Court decision ruling that he, and people like him, could not be confined due to the presence of mental illness alone. Donaldson’s case was an enormous legal victory for people with mental disorders.

Because the Court specifically forbade confining a “nondangerous” person who is “capable of surviving” in the community, the O’Connor case is often cited for the proposition that civil commitment – a restriction on liberty – is limited to people who are dangerous, whether to others or to themselves, such that they are incapable of surviving safely if free. Legislatures have included this dangerous requirement in their statutes, and courts interpreting it have specifically interpreted “dangerous” to mean imminently dangerous—or dangerous right now, at the time of the hearing. For example, if evidence indicates the person has ceased taking prescribed medication, and they are certainly going to decompensate and become dangerous in a few weeks, that is insufficient for commitment.

Is this requirement of danger, right now, too strict? Those who advocate for more liberal standards of commitment—desiring to offer involuntary treatment to a wider swath of patients—claim that O’Connor v. Donaldson does not exactly require dangerousness. In fact, as seen in the language quoted in this section, O’Connor forbids confinement of “nondangerous” people without “more,” and the Court never defines that “more.” Could it be that “more” includes a serious need for treatment? Or something else?

The argument that danger is not required by O’Connor is appealing to those who want civil commitment to be more available. This perspective suggests that people need help before they become dangerous, and that help should be provided, even if the person lacks the clear-mindedness to choose that help. Involuntary commitment could be used to treat a person who, for example, suffers from lack of insight as part of their mental disorder, and does not appreciate that they need treatment or medications. This person could, it is imagined, be helped at the first signs of deterioration rather than waiting until they are deeply psychotic and requiring a lengthy period of restorative treatment, possibly after hurting someone. Would this not be more efficient, more humane (Bloom, 2006)?

Setting aside the results for individuals, the general prospect of requiring danger in order to provide mental health treatment has bigger picture consequences. There is a powerful argument that the “dangerous” standard does not protect people with mental disorders, but rather hurts them. The “dangerous” standard may force society to allow people with mental disorders to become dangerous—fulfilling the negative thinking and stigma around people with mental disorders—before providing desperately needed help. This creation of danger, when alternatives exist, needlessly strengthens the negative public perception around mental illness and disability by effectively tying these conditions to dangerousness (Gordon, 2016).

The “gravely disabled” standard (or its variations), used in many states and discussed earlier in this chapter, has been an attempt to broaden the net for civil commitments outside of “dangerousness.” The idea behind these broader standards is to allow commitment of people who are experiencing severe deterioration and struggling to care for themselves—before danger is truly upon them. However, the gravely disabled or basic needs standards have often been viewed as still requiring, ultimately, dangerousness to self. In fact, many of the states that use this standard specifically include an element of “danger,” by inaction, in the requirement. Some statutes (including Oregon’s) specify that the grave disability results in serious harm (Bloom et al., 2017). It is unclear to what extent “grave disability” without resulting “danger” would be permitted as a basis for commitment under O’Connor—but perhaps a future Court case will tell us (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019).

9.3.3 The Requirement of Clear & Convincing Proof

Knowing that a person must be proved “dangerous,” in some sense, in order to commit them, the question arises as to how much proof of dangerousness is required. Just a few years after O’Connor v. Donaldson, the Supreme Court decided the case of Addington v. Texas (1979), which addressed this question of proof.

Like Kenneth Donaldson, Frank Addington had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, but unlike Donaldson, Addington was dangerous and probably needed to be committed. Addington had been threatening his mother, and according to doctors, he experienced delusions and had behaved in a dangerous manner repeatedly. Addington challenged his commitment in court, and the case went up on appeal, eventually to the Supreme Court. The issue before the Court was how much—or what level of—evidence should be required to support Addington’s commitment to the hospital. Addington, predictably, argued that it should be a lot of evidence, or as much as would be required to convict a person of a crime. The state, also predictably, argued that the evidence required was less, just a normal civil case. (Addington v. Texas, 1979)

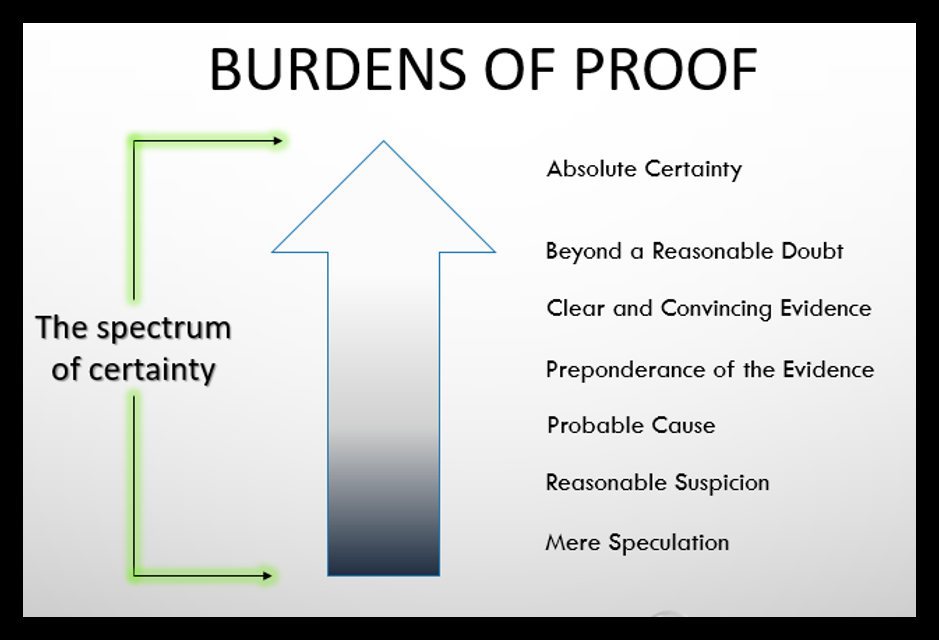

Typically, civil cases have a lower burden of proof, meaning the amount or level of evidence required to prevail, than criminal cases. Civil cases are generally lawsuits between private parties, such as cases involving contracts or money disputes. These cases are typically won with a preponderance of the evidence (often characterized as just enough to tip the scales, or 51%). Criminal cases, in contrast, require proof beyond a reasonable doubt to convict a person. Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is understood to mean overwhelming evidence which leaves no real doubt in the minds of decision makers. Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is not 100%, but it is somewhere closely below that level (figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4 shows the range of burdens of proof as a “spectrum of certainty.” Lowest on this list is a mere speculation. Certainty increases up from there to Preponderance of the Evidence in the middle, and Absolute Certainty at the top – beyond any of the levels required in court. The “burden” of proof gets harder as the need for certainty rises.

Addington argued that the state should be required to establish his suitability for involuntary commitment “beyond a reasonable doubt,” the same level required for a criminal conviction. The Texas Supreme court heard his case and decided that the normal civil standard of “preponderance” of the evidence was all that needed to be satisfied in a civil commitment case. The Supreme Court disagreed with both of them, finding that what was required was a less common, middle ground standard: clear and convincing evidence.

The clear and convincing standard of proof is more demanding than the preponderance standard, but less stringent than proof beyond a reasonable doubt. The Court wrote that this in-between standard of clear and convincing evidence was fitting the circumstances of civil commitment—which is more weighty than a typical civil lawsuit, but not quite criminal-level. The Court must weigh the “individual’s interest in not being involuntarily confined” against the “state’s interest in committing the emotionally disturbed [person].” 441 U.S. at 426. The Court emphasized that commitment is “a significant deprivation of liberty,” and found it “indisputable” that commitment will “engender adverse social consequences to the individual,” namely “stigma.” 441 U.S. at 427.

Though the Addington Court would not agree to require proof beyond a reasonable doubt, distinguishing civil commitment from criminal cases, the Court explained the need for at least the higher clear-and-convincing standard, in the interest of fairness:

“We conclude that the individual’s interest in the outcome of a civil commitment proceeding is of such weight and gravity that due process requires the state to justify confinement by proof more substantial than a mere preponderance of the evidence.”

441 U.S. at 428.

Under the Addington ruling, if a court considering civil commitment found that witnesses and other evidence indicated a person was just slightly more likely to be dangerous than not dangerous, that person could not be committed. The commitment judge would have to find that the person was far more likely to be dangerous than not dangerous—almost certainly so. This is a significant burden not lightly undertaken and not easily met, especially in a matter as complex as mental illness.

Like the O’Connor decision, the Addington decision serves as a limit on the use of civil commitment, and a reminder of the seriousness of this measure. While it is not a criminal conviction, commitment does require very substantial (clear and convincing) proof of a very serious concern (danger) before civil commitment can be used. In light of the historical disregard of rights of people with mental disorders, this is reassuring. Considering the need for protection and treatment of this vulnerable group, it is also potentially concerning.

9.3.4 Licenses and Attributions for Limitations on Civil Commitment

“Limitations on Civil Commitment” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.3. Photo of Kenneth Donaldson from Tampa Bay Times, https://www.tampabay.com/features/humaninterest/floridas-craziness-connected-to-kafkaesque-treatment-of-our-mentally-ill/2291870/, is included under fair use.

Figure 9.4. Burdens of Proof from Alaska Criminal Law – 2022 Edition by Robert Henderson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.