10.6 Environmental Inequity

Aimee Samara Krouskop and Kimberly Puttman

From an equity lens, there are two main ideas about the relationship between society and the environment. The first, as we described in Chapter 2, is the impact of human activity and decision-making. Environmental sociologists emphasize that environmental problems are the result of human decisions and activities that harm the environment. In the examples of environmental problems we’ve reviewed, the human factor is obvious: our personal behavior, the actions of corporations, and the weakness of government environmental regulation cause serious environmental problems that threaten the planet.

The second is the existence and consequences of environmental inequity. Recall from Chapter 3 that both globally and locally, our well-being is related to our social place (our intersecting racial, ethnic, and gender characteristics). Our social place influences our access to various environmental resources, including open spaces and nature (figure 10.26), clean water, and safe places during weather emergencies.

Inequity in Environmental Impact

Environmental inequity (also called environmental injustice) refers to the fact that low-income people and people of color are disproportionately likely to experience various environmental problems (Bullard and Johnson 2009; Mascarenhas 2009). They also experience inequity in environmental impact. These realities are due to unjust power imbalances in society that create an unequal distribution of resources. This unequal distribution is often the result of injustices against historically excluded groups of people.

For example, in 2021, nearly 1 million Californians lived with unsafe drinking water from a failing water system; more than two‑thirds of these were located in communities with significant financial need (Tilden 2022) (figure 10.27). To study this, we can ask: Which groups experience the impacts of environmental issues more than others? What are those impacts?

Human-Made Disasters

While human decision-making can harm the environment and therefore cause detriment to the human experience, human decisions made by people in power can also harm those with less access to resources. Sociologists McCarthy and King (2009) cite several environmental accidents that stemmed from reckless decision-making and natural disasters in which human decisions accelerated the harm that occurred.

One accident, the result of reckless decision making occurred in Bhopal, India, in 1984, when a Union Carbide pesticide plant leaked 40 tons of deadly gas. Between 3,000 and 16,000 people died immediately and another half million suffered permanent illnesses or injuries. A contributing factor to the leak was Union Carbide’s decision to save money by violating safety standards in the construction and management of the plant. Most who died were the poorest members of Bhopal, living in settlements near the factory (Broughton 2005; Agarwal 2022). Because of the resulting health issues survivors experienced, the gas leak entrenched their poverty and marginalization for following generations (“The Bhopal Tragedy: 30 Years of Injustice for Victims and Survivors” 2014) (figure 10.28).

Hurricane Katrina was another environmental and social disaster in which human decision-making resulted in a great deal of preventable damage (figure 10.29). After Katrina hit the Gulf Coast and especially New Orleans in August 2005, the resulting wind and flooding killed more than 1,800 people and left more than 700,000 homeless. McCarthy and King (2009:4) attribute much of this damage to human decision-making: “While hurricanes are typically considered ‘natural disasters,’ Katrina’s extreme consequences must be considered the result of social and political failures.”

Long before Katrina hit, it was well known that a major flood could easily breach New Orleans’ levees and have a devastating impact. Despite this knowledge, federal, state, and local officials did nothing over the years to strengthen or rebuild the levees. In addition, coastal land that would have protected New Orleans had been lost over time to commercial and residential development.

According to sociologist Nicole Youngman (2009:176), this development also “placed many more people and structures in harm’s way than had existed there during previous hurricanes.” All these factors led Youngman to conclude that Katrina’s impact “demonstrated how a myriad of human and nonhuman factors can come together to produce a profoundly traumatic event.” In short, the flooding after Katrina was a human disaster, not a natural disaster.

Hazardous Living Conditions

Outside of natural disasters, neighborhoods populated primarily by people of color and members of low socioeconomic groups are burdened with a disproportionate number of hazards, including toxic waste facilities, garbage dumps, and other sources of environmental pollution and foul odors that lower the quality of life.

All around the globe, members of minority groups bear a greater burden of health problems that result from higher exposure to waste and pollution (figure 10.30). This can occur due to unsafe or unhealthy work conditions where no regulations exist (or they are not enforced) for poor workers, or in neighborhoods that are uncomfortably close to toxic materials.

Research shows that in the United States, for many African-Americans, these inequities pervade all aspects of their lives. Examples include environmentally unsound housing, schools with asbestos problems, or facilities and playgrounds with lead paint. A 20-year comparative study led by sociologist Robert Bullard determined “race to be more important than socioeconomic status in predicting the location of the nation’s commercial hazardous waste facilities” (Bullard et al. 2007). His research found, for example, that Black children are five times more likely to have lead poisoning (the leading environmental health threat for children) than their white counterparts, and a disproportionate number of people of color reside in areas with hazardous waste facilities (Bullard et al. 2007).

Environmental Racism

Much of the heightened exposure to hazardous living conditions and disasters that Black families face is related to a form of systemic racism: environmental racism. Environmental racism is the deliberate targeting of communities of color for residence in areas more vulnerable to disaster, and the targeting of those residences for toxic waste disposal and the location of polluting industries. This targeting is done through policies and practices and includes the exclusion of people of color from environmental public policy-making (Chavis 2022). Our definition of environmental racism is informed by the work of the Reverend Ben Chavis, the originator of the term. We’ll learn more about Chavis in the Environmental Justice Movements section.

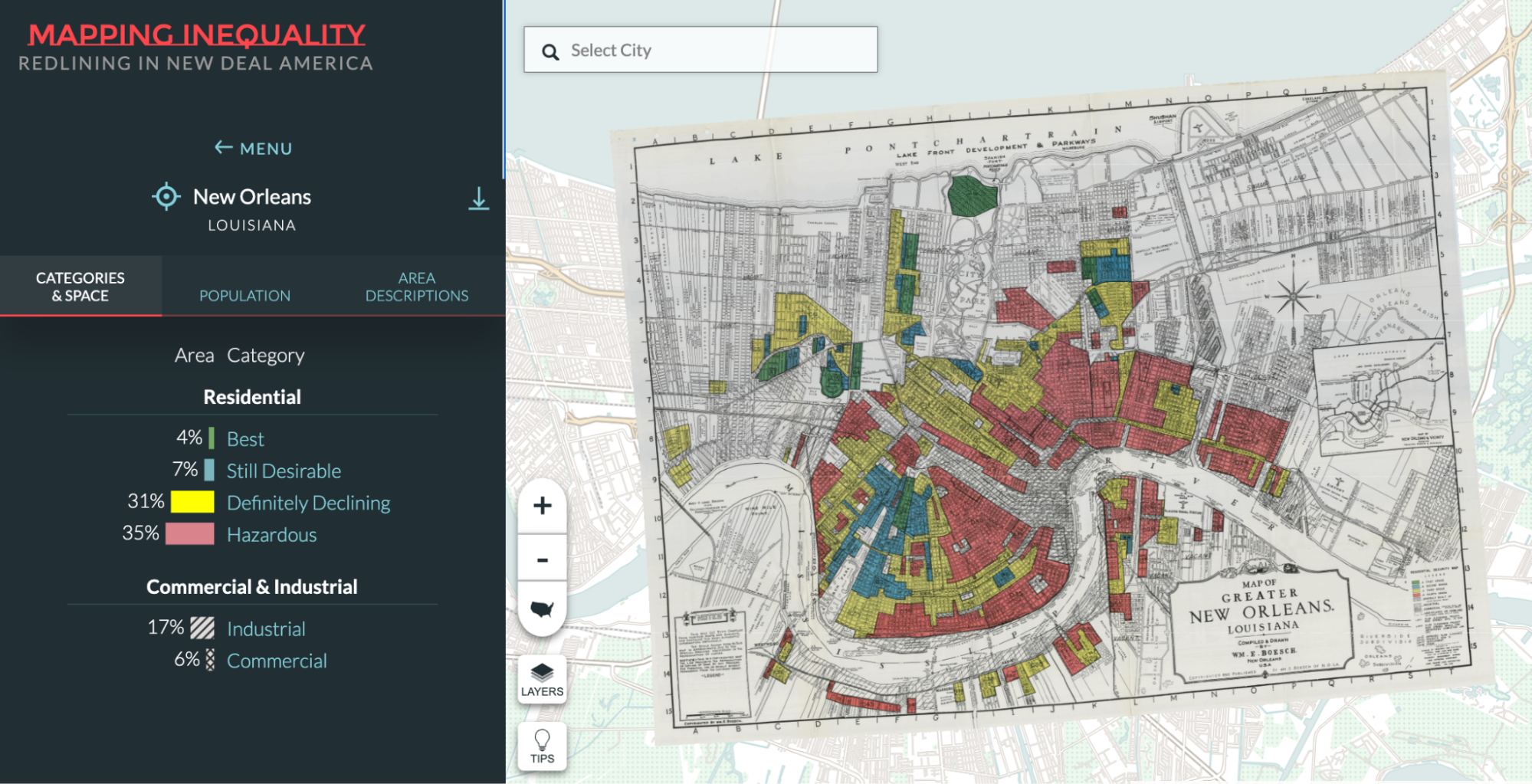

One example of environmental racism relates to the U.S. legacy of racist housing policies. The practice of redlining, the discriminatory housing practice we introduced in Chapter 3 and Chapter 8, has contributed significantly to segregating Black people in areas that incur lower levels of government support and protection than white neighborhoods.

Let’s look again at Hurricane Katrina. Take a few minutes to view the 1930s-era redlined map of New Orleans [Website] on the Mapping Inequality website (figure 10.31). Then, on the site, explore the box on the left to see how neighborhoods were graded and described.

Scientific American reports that “four of the seven zip codes that suffered the worst flood damage from Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans had Black populations of at least 75%” (Frank 2020). Sociologists Jean Ait Belkhir and Christiane Charlemaine add that people not living in poverty were able to escape due to their access to vehicles and credit cards.

However, the majority of Black and poor residents had no protection as the city had inadequate dikes, levees, and no evacuation plan. “Once the hurricane hit, the federal government was slow to respond. When it did, the saving of property was prioritized over the saving of people, and many people of color who were caught up in the evacuation decried the treatment they received.” In short, “exposure to the hurricane’s devastation was a function of place, race, gender, and class” (Belkhir and Charlemaine 2007:121).

This discrimination and the legacy of redlining have reinforced unjust living conditions for minority residents nationwide. A report conducted in 2021 by the real estate firm Redfin found that “formerly redlined neighborhoods have a larger share of homes endangered by flooding than neighborhoods that weren’t targeted by the racist 1930s housing policy” (Katz 2021).

Watch the 5-minute video “How Climate Change Is Making Inequality Worse” [Streaming Video] (figure 10.32). As you do, take note of the inequalities associated with climate change presented.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fHF4HHeOtkc

Taking a global view, we can peek into the work of the United Nations and its Sustainability Goal 10: reduce inequality within and among countries. The United Nations Environment Program focuses its work on Goal 10 with projects that reduce inequities related to the environment.

Pandemics and COVID-19

Consider what we’ve discussed about social place and our varied experiences with environmental change. What impacts do pandemics, as environmental issues, have on individuals in society, based on race, ethnicity, and gender?

The New York Times article “Virus Is Twice as Deadly for Black and Latino People Than Whites in NYC” reports that in 2020, the coronavirus was killing Black and Latino people in New York City at twice the rate that it was killing white people. The mayor of New York City reflected that this disparity matches the standard economic inequalities and differences in access to health care (Mays and Newman 2020).

Beyond New York City, the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed many inequities and social issues. They include racism in health systems, segregated health services, xenophobia against people from China and other parts of East Asia, and a severe lack of data on the impacts of the disease among Native Americans. These inequities are mimicked by other pandemics.

Inequity in Environmental Transition

Inequity in environmental transition refers to uneven investment in environmental solutions based on social place. That is, based on our social place, we receive different access to environmental solutions, and we receive different protections from environmental issues. Many policies and initiatives established as solutions to environmental issues ignore or harm people of color or women.

For example, environmental policies such as expansions of public transport, carbon pricing, and taxes affect women and poorer households negatively because these policies often overlook their needs. To illustrate, a public policy transit route might serve the 9-to-5 commuter but overlook the needs of mothers who must arrange for their children to get to school.

In another scenario, environmentally friendly cooking stoves were discontinued from a program when organizers realized their impact on emissions was smaller than initially expected. However, the stoves have improved women’s and children’s health and safety (Gloor et al. 2022) (figure 10.33).

The Luskin Center for Innovation at the University of California, Los Angeles, notes that wealthier households are typically the first to adopt renewable energy installations, such as rooftop solar panels. However, as these installations reduce energy costs, lower-income households would receive a greater benefit from renewable energy at home (UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation n.d.)

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change outlines the following three principles important in attaining equity in our environmental solutions:

- Distributive justice: striving for an equitable allocation of the burdens and benefits of solutions among individuals, nations, and generations.

- Procedural justice: paying attention to who participates in decision-making about environmental solutions.

- Recognition: having respect for, engagement with, and fair consideration of diverse cultures and perspectives (IPCC 2022).

Many thinkers and organizations are working on ways that equity in environmental transition can be improved. This collective goal is often called “Just Transition.” For example, Marybelle N. Tobias is the founder and principal of Environmental Justice Solutions. She is helping the City of Oakland make equitable decisions for its 2030 Equitable Climate Action Plan (figure 10.34). (Optional: Watch this 4:10-minute video, “Oakland 2030: Equity at the Center” [Streaming Video], by Marybelle N. Tobias to learn more about her work).

Our social place influences the degree of our exposure to harmful or dangerous elements in the environment. As societies build solutions to harmful environmental issues, our social place also influences our access to those solutions.

Going Deeper

- For more information on redlining, see Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America [Website].

- For a story on xenophobia in the time of COVID-19, listen to this 25-minute podcast by NPR: “When Xenophobia Spreads Like a Virus” [Podcast].

- For an overview of issues related to COVID-19 and inequity, browse through COVID-19 Racial Equity and Social Justice Resources [Website] at Racial Equity Tools.

Native American Tribes and Environmental Racism

Native Americans are unquestionably impacted by environmental racism. The Commission for Racial Justice found that about 50 percent of all Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans live in communities with uncontrolled waste sites (United Church of Christ 1987). There’s no question that, worldwide, Indigenous populations are suffering from similar fates.

For Native American Tribes, the issues can be complicated—and their solutions hard to attain—because of the intricate governmental issues arising from a history of institutionalized disenfranchisement.

Unlike other racial minorities in the United States, Native American Tribes are sovereign nations. However, much of their land is held in “trust,” meaning that “the federal government holds title to the land in trust on behalf of the tribe” (Bureau of Indian Affairs 2012). Some instances of environmental damage arise from this crossover, where the U.S. government’s title has meant it acts without the approval of the Tribal government. Other significant contributors to environmental racism as experienced by Tribes are forcible removal and burdensome red tape to receive the same reparation benefits afforded to non-Indians.

To better understand how this happens, let’s consider a few example cases. The home of the Skull Valley Band of Goshute Indians was targeted as the site for a high-level nuclear waste dumping ground amid allegations of a payoff of as high as $200 million (Kamps 2001). Keith Lewis, an Indigenous advocate for Native American rights, commented on this buyout after his people endured decades of uranium contamination, saying that “there is nothing moral about tempting a starving man with money” (Kamps 2001). In another example, the Western Shoshone’s Yucca Mountain area has been pursued by mining companies for its rich uranium stores, a threat that adds to the existing radiation exposure this area suffers from U.S. and British nuclear bomb testing (Environmental Justice Case Studies 2004).

In the “four corners” area where Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico meet, a group of Hopi and Navajo families have been forcibly removed from their homes so the land could be mined by the Peabody Mining Company for coal valued at $10 billion (American Indian Cultural Support 2006). Years of uranium mining on the lands of the Navajo of New Mexico have led to serious health consequences, and reparations have been difficult to secure; in addition to the loss of life, people’s homes and other facilities have been contaminated (Frosch 2009) (figure 10.35).

In yet another case, members of the Chippewa near White Pine, Michigan, were unable to stop the transport of hazardous sulfuric acid across reservation lands, but their activism helped bring an end to the mining project that used the acid (Environmental Justice Case Studies 2004).

These examples are only a few of the hundreds of incidents that Native American Tribes have faced and continue to battle against. Sadly, the mistreatment of the land’s original inhabitants continues via this institution of environmental racism. How might the work of sociologists help draw attention to—and eventually mitigate—this social problem?

Licenses and Attributions for Environmental Inequity

Open Content, Original

“Environmental Inequity” is written by Aimee Samara Krouskop and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 10.26. Merged photo from images in Central Park is on Flickr, by Rick Schwartz and licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

The definition of environmental inequity in “Inequity in Environmental Impact” and “Human-Made Disasters” are adapted from “20.4 Understanding the Environment” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Photos replaced or added.

Figure 10.27. A photo by Dorothea Lange is published by the Library of Congress with no known restrictions (left). A photo of Vue Her in Singer, California, is provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and published on Flickr, under public domain (right).

“Hazardous Living Conditions” is adapted from sections in “20.3 The Environment and Society” in Introduction to Sociology 3e. Photo added.

Figure 10.28. “In Bhopal, Thirty-Four Years After the Leak” is provided by Bhopal Medical Appeal and Rohit Jain and published on Flickr, under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 10.29. “Hurricane Katrina as it Approached New Orleans” was made available by the U.S. NOAA and published on Wikipedia (left). “FEMA Urban Search and Rescue Task Force Members” is made available by mad mags and published on Flickr, under CC BY-NC 2.0 (right).

Figure 10.30. “A Burning Site for the Recovering of Copper from Electronics Waste in Agbogbloshie, Accra, Ghana” is provided by Fairphone and published on Flickr, under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 10.31. Screenshot of a redlined map of New Orleans, Louisiana, from the Mapping Inequality Website, is published under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.33. “A Woman in Rwanda Cooks with Cooking Stove” by Rwanda Green Fund and is published on Flickr under CC BY-ND 2.0 (right). “Clean Cooking in Refugee Settlement” is published on Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 4.0 (left).

Figures 10.35. Two of the many paintings by Chip Thomas of the Navajo Nation (left and right). Both images are published by the Library of Congress here and here with no known restrictions.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 10.32. “How Climate Change Is Making Inequality Worse” is published on YouTube and licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 10.34. Screenshot of, and video, “Oakland 2030: Equity at the Center” is published on YouTube and licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

recognition that we do not all receive the same power and resources in society. This informs action to identify and dismantle systems of power, privilege, and oppression.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

the fact that low-income people and people of color are disproportionately likely to experience various environmental problems.

differences in access to resources or opportunity between groups that are the result of treatment by a more powerful group; this creates circumstances that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

an organization of workers who work together to improve their wages and working conditions.

the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

a form of systemic racism created by policies and practices that disproportionately force communities of color to live near toxic waste and airborne matter, burdening them with health hazards.

the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, concerning the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

the discriminatory practice of refusing loans to creditworthy applicants in neighborhoods that banks deem undesirable.