8.3 Perspectives on Education in Unequal Societies

When sociologists study the social institution of education, they focus on various questions. Often, those questions fit within the theoretical frameworks we introduced in Chapter 3. Functionalists, for example, ask how schools are instrumental in helping societies agree on morals and what is acceptable behavior. Conflict theorists ask how education supports the power of the dominant class. They see that gender, race, ability, or other social locations impact who teaches and who learns. Symbolic interactionists focus their inquiry on how people interact in educational settings, and the symbols, meanings, and consequences related to those interactions. Let’s look at those questions and perspectives in the context of unequal societies.

Democracy and Americanization: A Functionalist View

If you were to ask students around the world what education means to them (figure 8.6), you would receive many different answers based on their life circumstances. But most would point to specific life functions that schooling prepares them for. That might be gaining employment, supporting their family, or fulfilling life goals.

When studying education and social change, functionalists focus on the positive functions that education fulfills. They contend that education contributes to two kinds of functions for society. The first is manifest functions, which are the intended and visible functions. The second is latent functions, which are hidden, not recognized, or unintended functions.

Manifest Functions

One major manifest function associated with education is socialization. In the late 19th century, the French sociologist Émile Durkheim characterized schools as “socialization agencies that teach children how to get along with others and prepare them for adult economic roles” (Durkheim 1956) (figure 8.7). Since then, sociologists have extensively discussed the role of schools in producing a workforce for society. But socialization in schools also involves learning the values and norms of the society as a whole. Specifically, schools teach the values and norms of dominant culture.

Two of the most widespread dominant U.S. values students learn are individualism and competition. Instructors socialize students to value individualism and competition by openly rewarding the “best” individual. U.S. schools also teach patriotism as a cultural value, with associated norms and rituals. For example, students recite the Pledge of Allegiance each morning and learn about national heroes and the nation’s history (figure 8.8).

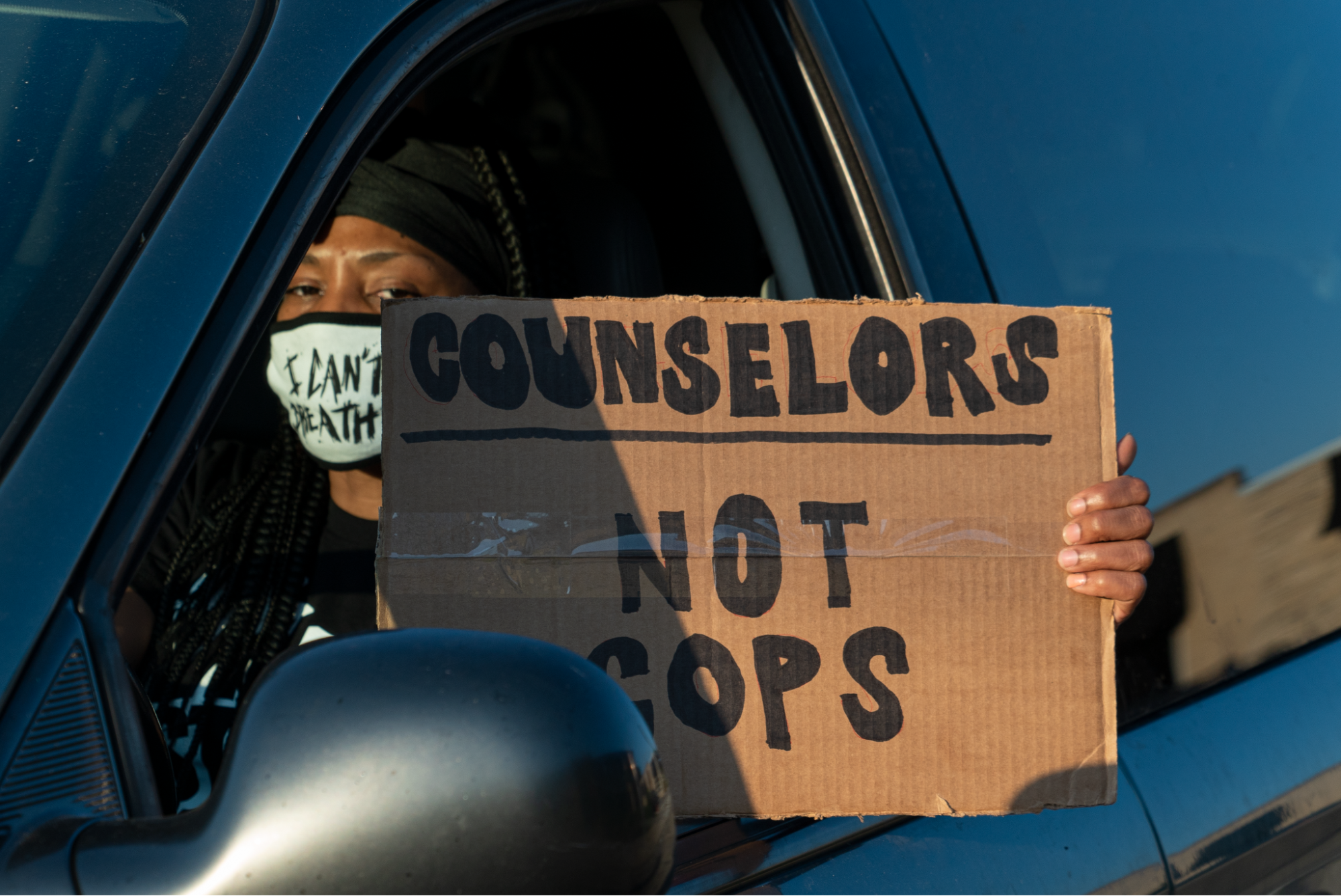

Educational systems also serve a manifest function of social control. Social control happens as instructors and school leaders encourage—and sometimes force—compliance with the norms of dominant society. For example, U.S. schools have established comprehensive systems for punishment, ranging from solitary confinement to interactions with campus police officers. Punishments are explained by school personnel as necessary to better equip students to navigate the authorities in the world. However, there are important implications to this system.

First, many punishment methods in schools normalize violence and isolation as forms of discipline (Michaelson and Durrant 2020). Sitting in a corner or expulsion is common. Nineteen states in the United States still allow corporal punishment (physical punishment intended to cause physical pain or discomfort) in the classroom, even though research shows that it’s not effective in redirecting student behavior (Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor 2016; Regev et al. 2012) (figure 8.9).

Second, Black and Brown youth are treated with discrimination (Gershoff 2016). For example, the school-to-prison pipeline refers to a national trend that funnels students out of public schools and into the juvenile and criminal legal systems. Many of these youth are Black or Brown and would benefit from additional support and resources. Instead, they are isolated, punished, and pushed out through “zero-tolerance” policies and the criminalization of minor infractions of school rules. As law enforcement officers have been increasingly assigned to schools, students are exposed to an institution that has a history of institutional racism.

Education, being used for socialization and social control with discrimination, has a long history in the United States. After the Revolutionary War, then again in the mid-1800s, government leaders wanted to establish a common set of shared values for the nation: freedom, liberty, patriotism, and unity. They aimed for a democracy: a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.

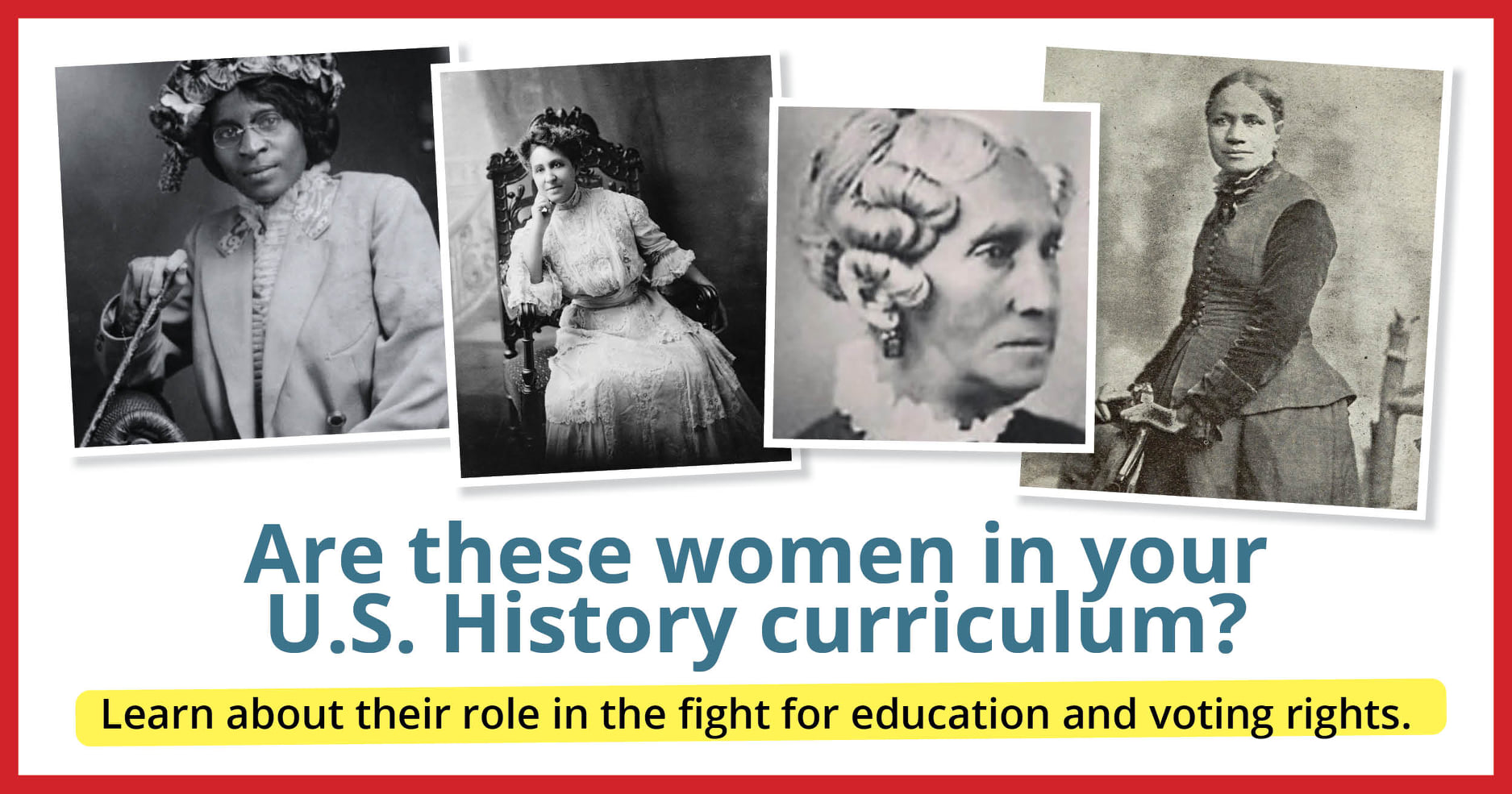

On one hand, early U.S. leaders argued that the democracy they strived for depended on freemen (those not enslaved or living as serfs) being able to read and write. Education was championed, particularly for families who were immigrants or poor (Bandiera et al. 2018) (figure 8.10). So through shared values, there could be more social stability in a rapidly expanding country. However, it was illegal for enslaved people to receive an education (and in some states, illegal for freed Blacks). Textbooks transmitted ethnic, racist, and sexist prejudices. This idealistic vision of a democracy of people unified with free and universal education was a myth.

This myth plays out in many ways today. In some U.S. schools, there are vast omissions related to slavery, genocide of Indigenous Peoples, forced displacement, and lack of recognition of women’s contributions to society (figure 8.11). Or reconsider the two groups of students reciting the Pledge of Allegiance in figure 8.8. At least two of the Japanese-American students shown there were forced into World War II internment camps soon after the photo was taken (Library of Congress n.d.). And Hawai’i, where the other students live, became a U.S. state after a U.S.-led illegal coup. Despite these conflicts, students were asked to express patriotism.

Latent Functions

Education also fulfills latent (hidden, not recognized, or unintended) functions. One important example, more often seen on university campuses, is providing a place for students to learn about and act on social issues. In 2011, the Occupy Wall Street movement swept across college campuses all over the United States (figure 8.12). The movement brought diverse groups of students together to address social and economic inequality. This is essentially a function of education that serves democracy.

Other latent functions, like their manifest cousins, have mixed implications when examined with an equity lens. For example, in school and college, students establish peer relationships and develop what sociologists call social networks. As we described in Chapter 2, social networks are social structures that exist between individuals and organizations. Social networks are important for connecting individuals through familiarity and for sharing access to resources.

In the educational setting, classmates or sports teammates might become friends, share tips on homework or dating, provide connections to extracurricular events, and offer access to myriad resources related to doing well in life. Those networks might last well beyond school years. The connections can help members access resources such as advanced education, jobs, or financial opportunities. However, membership in groups that have more financial and educational resources is often “pay to play.” That is, you have to pay extra fees to join activities or have specific clothing or equipment to be part of those groups. And even when there isn’t a financial barrier, you may not have time for extra socializing if you need to work and go to school at the same time. This function of education that leads to professional networking is only accessible to people with expendable income (Renn 2022).

Improved socioeconomic social status has also been traditionally identified as a latent function of education. However, education is not guaranteed to work this way. Social status requires access to social networks that are not available to some. Furthermore, some have access to better education than others. Even if direct access to education is the same, if students are not associated with the class and culture of the dominant society, they can experience obstacles to receiving an equitable education.

In the next section, we’ll discuss social capital, which dives further into the unequal implications of social networks. We’ll also discuss education’s impact on social mobility and how well this applies across groups of diverse social locations.

Poverty, Wealth, and Intersectionality: A Conflict Theory View

As students are asked about the meaning of education for them (figure 8.6), their responses will inevitably differ greatly based on their social location. Education for some means that they can help their families eat and maintain shelter. If you are a new immigrant student, education might simply mean gaining a better chance of doing well in your new home. If you are a girl in many parts of the world, education may be something that is even difficult to imagine obtaining (figure 8.13). Education for others means they can pursue the career that interests them the most.

Conflict theorists in sociology look at how education maintains or challenges unequal social power. As we examined in Chapter 3, students from under-resourced communities don’t receive the same educational opportunities as their more affluent peers, even when they have the same intellectual potential and are equally hard-working. This inequality helps to maintain existing structures of power across generations. Conflict theorists also examine students’ experiences through the lens of other intersecting social locations, as education reinforces and perpetuates social inequalities.

Social Mobility

One of the critical questions sociologists examine when they consider education and social change is whether education actually makes a difference in an individual’s life or the quality of life in a society. A common saying for those who work to end family poverty is “there are two ways out of poverty—education and savings.” Is this really true for all families?

Getting out of poverty, or changing one’s quality of life, is considered social mobility. As we described in Chapter 3, social mobility is an individual’s or group’s movement through the class hierarchy due to changes in income, occupation, or wealth. Families are an important group to consider with social mobility. When we consider the dream of immigrants to the United States in the past and today, many say that their aspiration is to work hard so that their children can have a better life than they do. Over time, individuals and families can get richer or poorer, moving between social classes. Education can contribute to social mobility, but many other influences impact a person’s relative ability to benefit from education and their potential for social mobility.

Early conflict theorists identified schools as designed to train working-class students to accept and retain their position as lower-class members of society (figure 8.14). They argue that our educational systems disperse resources with inequity, allocating more resources and opportunities to students in richer neighborhoods (Lauen and Tyson 2008). This inequity creates barriers to escaping poverty or improving the quality of one’s life. In Chapter 3 we introduced the inequities in education that exist in the United States based on intersecting social locations. That is, students from families with more wealth and income are more likely to have better access to educational opportunities and better chances of educational attainment.

Tracking

Tracking is considered one of the barriers to benefiting from education for some. Tracking is a formalized sorting system that places students on “tracks” (advanced versus low achievers) that perpetuate inequalities. Some educators believe that students do better in tracked classes because they are with students of similar ability and may have access to more individual attention from teachers. However, conflict theorists argue that tracking leads to self-fulfilling prophecies in which students live up (or down) to teacher and societal expectations (Education Week 2004).

Race, ethnicity, and gender-based tracking are easy to see in historical examples. In the early 1900s, Mexican-American children attended segregated schools, which deliberately defined what they could learn based on their ethnicity and their gender. For example, in 1923 in San Fernando, California, the Mexican Industrial School defined the curriculum in this way:

Girls will have more extensive sewing, knitting, crocheting, drawn work, rug weaving, and pottery. They will be taught personal hygiene, homemaking, and care of the sick. With the aid of a nursery, they will learn the care of little children. The boys will be given more advanced agriculture and shop work of various kinds (Los Angeles School Journal 1923 in Gonzalez 1996:47).

Mexican-American students in the United States were not only segregated, but they were also tracked into gender-specific vocational occupations.

But tracking is not just a historical practice. One way to see tracking today is by examining the Advanced Placement (AP) courses. The degree to which students have access to AP courses, and the rates by which they pass the AP test, all vary significantly by race and ethnicity, class, and geographic location. Researchers estimated that during the 2015–2016 school year, Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic students and students from rural areas had less access to AP exams. Indigenous and rural students were most likely to attend a high school with no AP offerings (Chatterji et al. 2021). These differences continue when you look at the amount of school support offered to students to learn the AP content and then actually take the test.

Social and Cultural Capital: A Symbolic Interactionist View

Let’s look one more time at what the diverse responses from students around the world might be when asked what education means to them (figure 8.6). As we described, responses will vary depending on their class, race, ethnicity, and gender. They will also vary according to their culture of origin. For example, if students were raised in an upper-class family, it might be important to them to achieve a final doctorate degree to meet the expectations of their social circle. If they were raised on a Native American reservation, they might find the most value in devoting their education to the betterment of their community.

Inquiry about meaning is at the core of symbolic interactionism. In the context of education, this perspective focuses on the cultural symbols present (gestures, signs, objects, signals, and words) in an educational setting. The meaning of those symbols is created through interactions, so everyone can understand that educational setting. For example, what meaning is there to desks and chairs in classrooms all facing forward in a row versus in a circle? How do the communication and language of principals influence the experience of teachers? How does social interaction with teachers affect how well students learn?

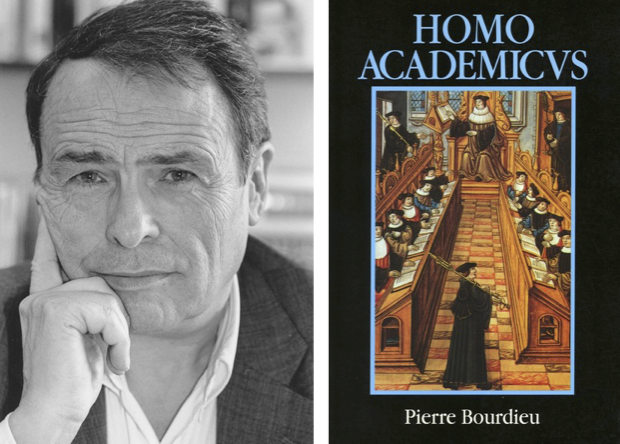

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu studied interactions in the context of social capital and cultural capital (figure 8.15). Social capital is the social networks or connections an individual has available to them due to group membership. Cultural capital is the cultural knowledge and items that help us navigate a society. It includes tastes, mannerisms, skills, material belongings, and credentials.

When expressions of cultural capital are shared, like specific tastes in music or how you hold your utensils, groups create a sense of collective identity. The degree to which members understand and follow the cultural capital of a group establishes their social position.

Applied to education, the kind of cultural capital a student has alters their experiences and opportunities in school. Because students of upper and middle classes are more likely to be raised by parents who graduated from college or have a college degree, they will enter school with more cultural capital to navigate the formal state-run educational systems than families of lower-class status. Ways of interacting and producing work, as well as understanding instructions and tests, are often the cultural capital of society members with more power and resources. This leaves others struggling to identify with cultural values and competencies outside their social group.

For example, there has been a great deal of discussion over what standardized tests such as the SAT really measure. Many argue that the tests group students by cultural capital rather than by natural intelligence. Consider the example SAT question used in the late 1980s in figure 8.16.

Most students probably know what a runner is and what a marathon is. However, many of the possible answers require specific cultural or class knowledge. In general, words like embassy, oarsman, regatta, and stable are typically used only by upper-class people in everyday life, which puts students from lower-income families at an unfair disadvantage. Passing the test is therefore based on cultural knowledge that some students do not have access to.

Colleges and universities are beginning to recognize that these and other standardized admissions tests are racially, ethnically, and culturally biased. Some schools are not using the test scores, and others are making the test optional (Carey 2023).

The power of cultural capital as a resource points to another concept examined in sociology, hidden curriculum. Hidden curriculum refers to the implicit social and cultural expectations, designed by dominant culture, that inform the educational process. This hidden curriculum reinforces the positions of those with higher cultural capital and bestows status unequally.

For example, consider how part of doing well in college is about following specific expectations of engaging in class, or understanding why an instructor would have office hours, or knowing that you can ask for an incomplete grade. Fifty-six percent of U.S. college students are the first in their families to attend college (Renn 2022). A first-generation student may not know these basic routines and practices of a college or university.

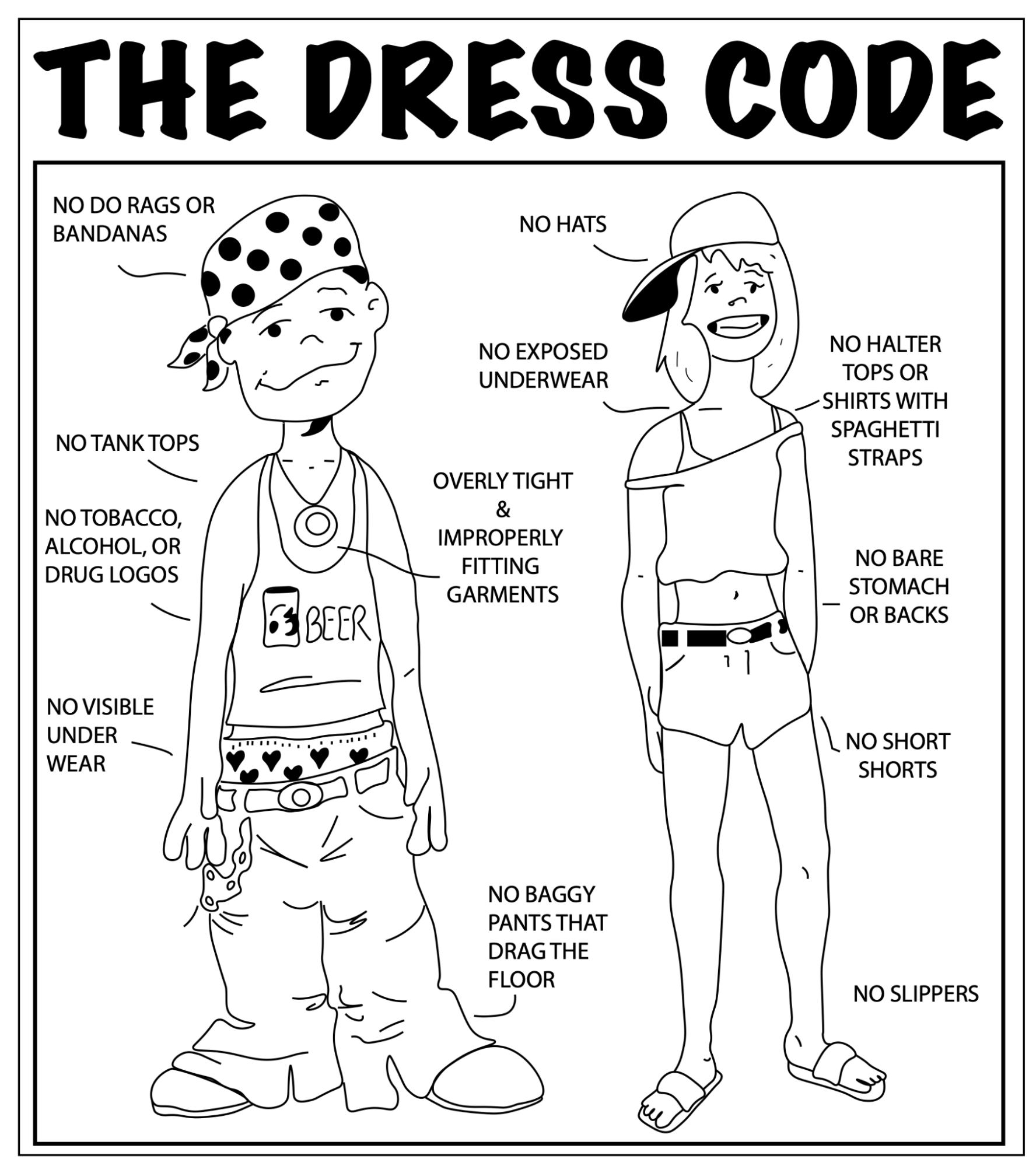

Hidden curriculum can go much deeper than these basics. First, critical theorists consider the socialization of students to strictly follow individuals in authority and take their rewards and punishments seriously as part of a hidden curriculum. There’s an irony that, although teachers convey the positive values of democracy in their political science curriculum, schools are rarely run democratically. Second, students are expected to follow the norms and values related to the dominant culture, which gives more validation to white, male, Christian, and cisgender bodies.

We can see this clearly in school dress codes, as they regulate which bodies are acceptable and which are not. For example, many dress codes prohibit wearing hats, do-rags, bandanas, or hijabs. This prohibition is racially and ethnically discriminating and supports oppression based on religion. In many cases, head coverings express a person’s racial, ethnic, or religious identity.

Another example is when dress codes prevent girls (but not boys) from wearing spaghetti straps or other clothing that shows too much skin (figure 8.17). Applying these rules to just girls is sexist. Professor of education Rouhollah Aghasaleh adds that this rule becomes part of supporting rape culture because the rules blame the survivor of sexual violence for “inciting” the attack, rather than holding the perpetrator responsible (Aghasaleh 2018).

Dress codes are also often written with gender binaries in mind. If a person is genderfluid or non-binary, they are invisible and unrecognized in the eyes of the school administration. If transgender or genderqueer students are forced to conform to gender-restrictive codes, they may have to do so at the cost of their identity. Social scientists point out that the results of this hardship may mean decreased academic success, more disciplinary issues, homelessness, and eventually incarceration (Greytak et al. 2009; Grant et al. 2011 in Glickman 2016).

Dress codes, as elements of hidden curriculum, reinforce the power, values, and behaviors of the dominant class. As Aghasaleh explains: “…our textbooks, teaching strategies, and instructional guides all tend to discriminate against bodies that do not fit” (Aghasaleh 2018:99). Non-white, lower-class, and female bodies are considered “disruptive, dangerous, or distracting” (Aghasaleh 2018:104). What is your assessment? Does the dress code in figure 8.17 sexualize women, support racism, or marginalize queer or non-binary students?

The concepts of social capital, cultural capital, and hidden curriculum are useful in explaining and predicting educational success in the U.S. mainstream educational scene. However, it’s important to acknowledge that they are based on the assumption that conforming to white dominant cultural practices, beliefs, and values is the only way to achieve educational (and life) success.

Labeling

When he was 23 years old, recent Stanford graduate Jeremy Iversen went undercover, posing as a high school student at a California high school. Out of that experience, he wrote the book High School Confidential, an account of the life experiences of Millennials. One of the problems he identified in his story is that of teachers applying labels to students.

Labels such as “easily distracted” or “ideal pupil” might seem to be helpful hacks for overburdened teachers as they struggle to give students what they need. A student learning English as a second language may be assigned classes to enhance their English skills. An autistic child will be given plenty of routines.

However, when students hear their labels from a person with authority over them and are treated as their label throughout the year, it can be detrimental to their schooling. If the label is a negative one, the student might begin to “live down to” that label. Sometimes these messages are extreme. One teacher, unaware that Iverson was a bright graduate of a top university, told him he would never amount to anything (Iverson 2006). Such labels are also difficult to “shake off,” which can create a self-fulfilling prophecy (Merton 1968).

Symbolic interactionists are interested in labeling as it relates to student-teacher interactions. A conflict theorist might add that this labeling is integrally related to inequities in the structure of education. For example, racially biased testing, as we discussed earlier with the SATs, may lead to a student being unfairly labeled a low achiever.

Credentialism

Closely related to labeling is credentialism, or the assumption of social superiority and inferiority based on formal educational attainment. In mainstream U.S. culture, credentials come in the form of diplomas, certificates, or awards we have achieved from formal institutions (figure 8.18). They serve as indicators of achievement, knowledge, and ability.

Credentialism is also an ideology that places formal education as superior to other ways of understanding human potential and ability. Ultimately, credentials are part of determining social status in the U.S. dominant society, prompting unequal life opportunities both during the process of education and in one’s career.

Going Deeper

To learn more about education and social mobility, watch “How America’s Public Schools Keep Kids in Poverty” [Streaming Video].

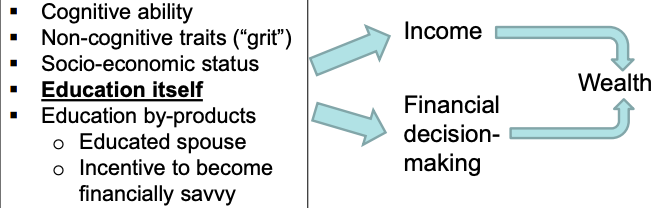

To understand more about the connections between education level and social mobility, take a look at this model. It was developed by economists from the Federal Reserve Bank. They studied wealth defined as owned land, savings, stocks, buildings, or businesses, and proposed the following relationship between education and wealth in the United States (figure 8.19).

In the first column, the researchers list characteristics that might influence a person’s attainment of wealth:

- Your cognitive ability

- Other traits related to success (such as “grit,” or how persistent you are)

- Your socioeconomic status

- Education itself

- Byproducts that come as a result of your level of education. These include the likelihood you will marry a similarly educated spouse and the likelihood that if you are born into a higher socioeconomic bracket, you’re more likely to live longer. This incentivizes people to do financial planning and allows investments to grow.

All of these factors both increase income and lead to better financial decision-making. Increased income and better financial decision-making influence the acquisition of wealth. This study concludes that it’s not education itself that directly leads to wealth. Rather, people who are wealthy already are more likely to have access to education and attain higher educational outcomes (Emmons 2015).

Licenses and Attributions for Perspectives on Education in Unequal Societies

Open Content, Original

“Perspectives on Education in Unequal Societies” by Kimberly Puttman and Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Democracy and Americanisation: A Functionalist View” includes adapted content from “16.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Education” in Introduction to Sociology 3e by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Kimberly Puttman and Aimee Samara Krouskop licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 include expanding and rewriting, including images, the addition of social change examples, and notes to highlight inequality.

Figure 8.6 “Education can be a force for stability and for change” is on Flickr, by UNICEF Ethiopia, and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 8.7. “Parachute” is on Flickr, by Jim George and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (left). “Little Tiny Cop” is on Flickr by Angelina Earley and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (right).

Figure 8.8. “Pledge of Allegiance” by Dorothea Lange is on Flickr and in the public domain (left). “A Teacher and Fourth Graders in Honolulu, Hawai’i” by Greg Concilla is on Flickr, provided by Waikiki Natatorium and licensed under CC BY 2.0 (right).

Figure 8.9. “Counselors Not Cops” on Flickr, by Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association (MTEA) and licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 8.10. “Detail from Government Mural” by Elihu Vedder, is on Wikipedia and in the public domain.

Figure 8.12. “Occupy Harvard Tents in Harvard Yard” is on Wikimedia Commons, by Occupy Harvard and is in the public domain.

Figure 8.13. “Pakistani teenager Malala Yousafzaï” is on Flickr, by European Parliament and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 8.14. “Lunchroom Equipped by Boys and Conducted by Girls” is in the public domain. Courtesy of the National Photo Company Collection (Library of Congress).

“Tracking” definition taken from “16.2. Theoretical Perspectives in Education” in Introduction to Sociology 3e by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.15. “Pierre Bourdieu, Portrait” by Bernard Lambert, is on Wikipedia and licensed under CC-BY-SA (left).

Figure 8.18 “Kindergarten Graduation” is on Flickr, by ktbuffy, and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 8.19. This model of education is found in the presentation, “Education and Wealth: Correlation Is Not Causation” by William R. Emmons and Society for Financial Education and Professional Development, included under fair use.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.6. “What Does Education Mean to You?” by UNICEF is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 8.11. “Are These Women in Your U.S. History Texts?” is published on the Zinn Education Project Facebook page and included under fair use.

Figure 8.15. “Homo Adacemicus Book Cover” by Stanford University Press is included under fair use (right).

Figure 8.16. “SAT Test Question” is published in the article, “The Cost of Good Intentions: Why the Supreme Court’s Decision Upholding Affirmative Action Admission Programs Is Detrimental to the Cause,” by Leslie Yalof Garfield and included under fair use.

Figure 8.17. “Dress Code” appears in the article “Dress code set for Darlington Co. students” (creator unknown). It was traced to improve image quality by Katie Losier and included under fair use.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

the lifelong process of an individual or group learning the expected norms and customs of a group or society through social interaction.

patterns of behavior that we recognize in each other that are representative of a person’s social status.

the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

a way to regulate, enforce, and encourage conformity to norms both formally and informally.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.

the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group.

recognition that we do not all receive the same power and resources in society. This informs action to identify and dismantle systems of power, privilege, and oppression.

the rank, honor, or prestige attached to one’s position in society or a group.

the social networks or connections that an individual has available to them due to group membership.

an individual’s or group’s (e.g., family) movement through the class hierarchy due to changes in income, occupation, or wealth.

a science guided by the understanding that the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

differences in access to resources or opportunity between groups that are the result of treatment by a more powerful group; this creates circumstances that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair.

a formalized sorting system that places students on “tracks” (advanced versus low achievers) that perpetuate inequalities.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the cultural knowledge and items that help one navigate a society.

the implicit social and cultural expectations, designed by dominant culture, that inform the educational process.

the systemic and extensive nature of social inequity and harm woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness.

a communally organized and persistent set of beliefs, practices, and relationships that meet social needs and organizes social life.

the assumption of social superiority or inferiority based on formal educational attainment.

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

a combination of a person's or family's economic and social position in comparison to others.