8.4 Policy Matters for Social Justice

One of the key drivers toward improving equitable access to education is government policy. In the Chapter Story, we introduced Indigenous communities in Bolivia and Colombia that see education as a force to create a more just society. Change in education in those countries has depended on students and teachers engaging in critical analysis while being deeply rooted in their communities and the environment.

Those qualities have been coupled with Indigenous-led civic action to transform education policy in government. In Bolivia, activists have achieved constitutional changes at the national level that grant more access to culturally relevant education that better serves students. These transformations in the institution of education provide a remarkable example of social justice.

Social justice is achieved when “everyone has fair access to the resources and opportunities to develop their full capacities, and everyone is welcome to participate democratically with others to mutually shape social policies and institutions that govern civic life” (Bell 2023). Policy related to the institution of education is crucial for achieving social justice. In this section, we look at three ways that education policy can play a role in changing educational systems and advance social justice.

Unequal Access

As we discussed earlier in this chapter, education for the “common man” was a core principle in establishing democracies in the late 1700s and early 1800s. However, in the United States, we haven’t yet achieved universal access to education, nor equitable ability to participate in education regardless of social location.

Segregation

One set of obstacles that exists in every state’s education system is segregation and lack of protection for students based on social location. Early education systems in the United States were segregated by law. Even when education was legal for many marginalized groups, it was in separate, segregated facilities that often provided lower-quality education. Or it was education that enforced oppression, and genocide. Educator and educational researcher Gloria Ladson-Billings summarizes part of this history:

In the case of African Americans, education was initially forbidden during the period of enslavement. After emancipation, we saw the development of freedmen’s schools whose purpose was the maintenance of the servant class. During the long period of legal apartheid, African Americans attended schools where they received cast-off textbooks and materials from White schools….Black students in the south did not receive universal secondary education until 1968 (Ladson-Billings 2006:5, italics added).

To the extent that higher education was possible for Black students, it was in schools established to primarily serve African Americans because admission was not possible in white universities. This segregation led to significant unequal outcomes in education. At the same time, African Americans responded resourcefully to create the educational institutions they needed (figure 8.20). Those schools established for African Americans were a resilient response. Many still exist, including the first: Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, which was established in 1838.

Today, in addition to providing the formal education needed to navigate U.S. society, these Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) also build economic wealth. Nathenson (2019) found that while HBCUs enroll far more low-income students than predominantly white institutions, more students experience upward mobility at HBCUs than at white institutions. For example, their calculations show that two-thirds of low-income students at HBCUs end up in at least the middle class.

Segregation happens to Latinx students as well. Earlier in this chapter, we introduced the experience of students who attended segregated schools for Mexican-Americans and who were tracked into ethnic and gender-specific classes. Mexican-American parents fought this segregation.

In California, parents Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez, who were Mexican and Puerto Rican, argued that their children deserved the right to go to the neighborhood school, rather than a school that Latinx students were restricted to. They organized other parents, boycotted schools, and sued the school district. Eventually, in 1947, school segregation based on ethnicity and language became illegal in California (Gonzales 1996:50) (figure 8.21). This case was foundational for further civil rights work, including national school desegregation (Robbie 2002).

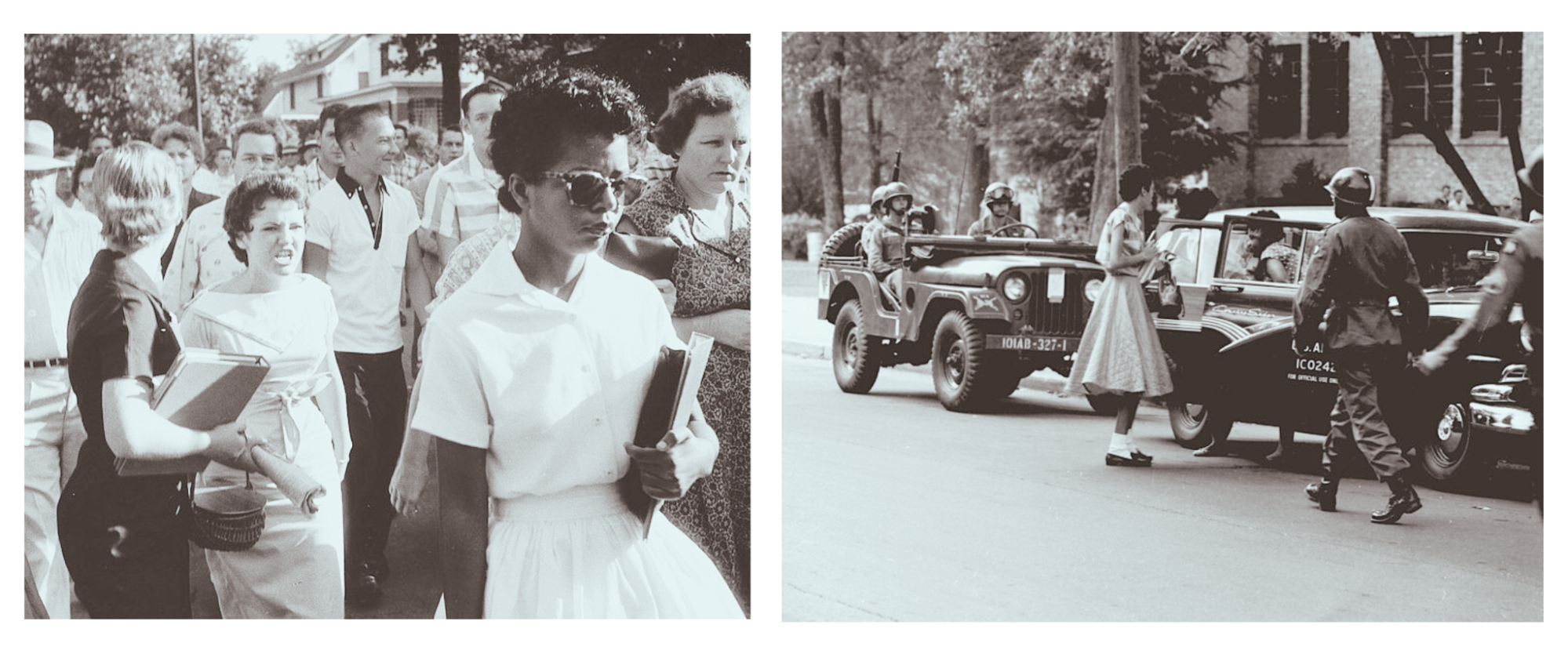

Nationally, state-sponsored racial segregation of public schools and other public spaces became illegal with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v Board of Education (U.S. Supreme Court 1954). This change in federal law resulted in passionate and often violent conflicts over integrating schools. One group of students in Little Rock, Arkansas, was the first to integrate a high school as a result of Brown. They were known as the Little Rock Nine.

These nine Black high school students faced violent white mobs protesting their attendance, and President Eisenhower was forced to authorize the National Guard and the Air Force to protect them. Only one of the Little Rock Nine graduated from Central High. The governor closed the school for a year to prevent integration, so the other students graduated from different high schools (figure 8.22).

Since 1954, many more laws have been passed that prohibit educational segregation and require integrated schools. For example, in 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, which prohibited discrimination based on race, color, ethnicity, and national origin. Title IV of this act prohibits segregation in schools. Title VI prohibits discrimination based on race, color, ethnicity, and national origin for any programs that receive federal funds, including schools and colleges.

Later measures outlawed discrimination based on sex (Title IX). Title IX opened the doors of education even wider to women, because colleges could no longer use sex as a reason to admit or fail to admit students. It also resulted in funding for women and for women’s sports. More recently, this amendment has been used to protect LGBTQIA+ students from discrimination in public and private schools, at least legally.

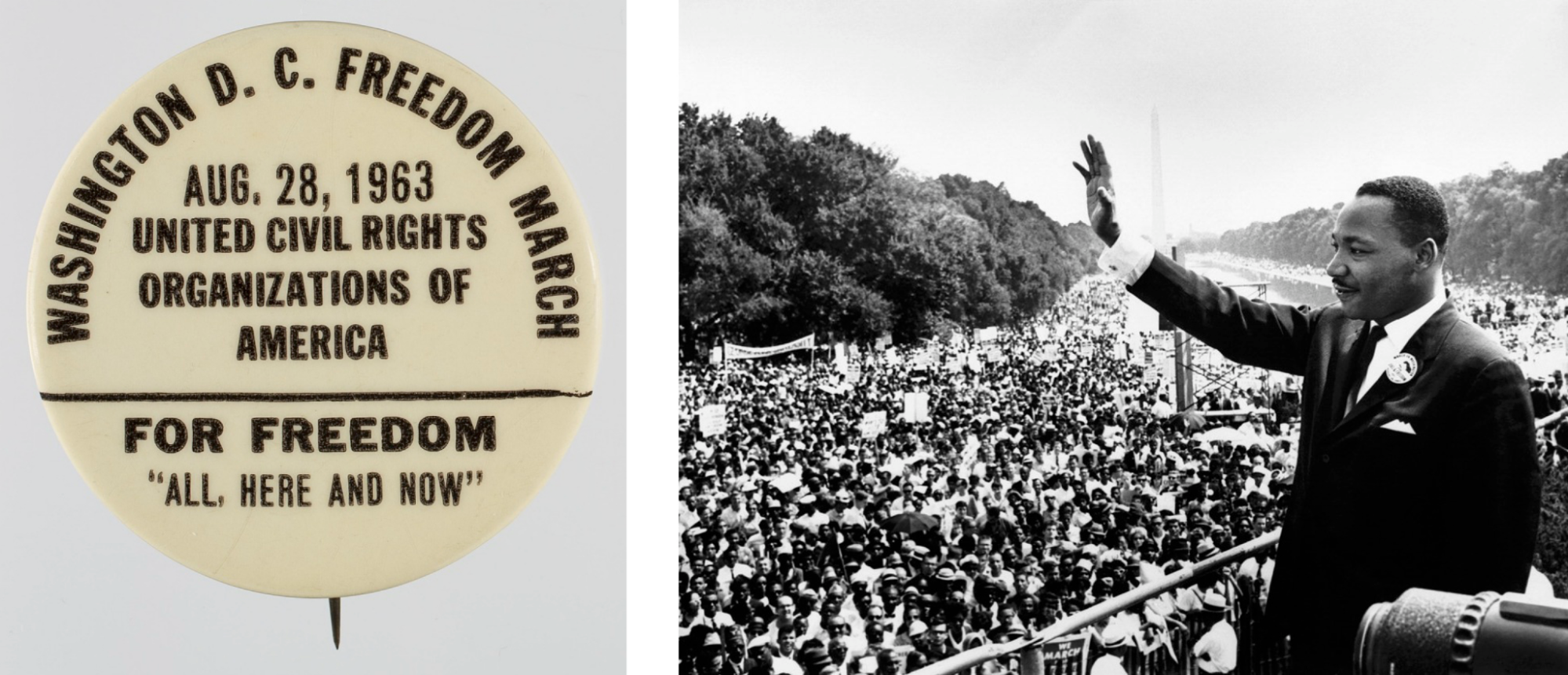

These legal changes were the result of fierce activism by Black, Brown, and white people, marked historically by the 1963 Freedom March of more than 200,000 demonstrators (figure 8.23). The march was successful in pressuring the administration of President John F. Kennedy to initiate the federal civil rights bill in Congress.

De Facto Segregation

Changes in federal and state laws are only one step in the process of creating social change for educational equity. Educational segregation is illegal. But de facto segregation, the segregation that occurs without laws but because of other social influences, still exists.

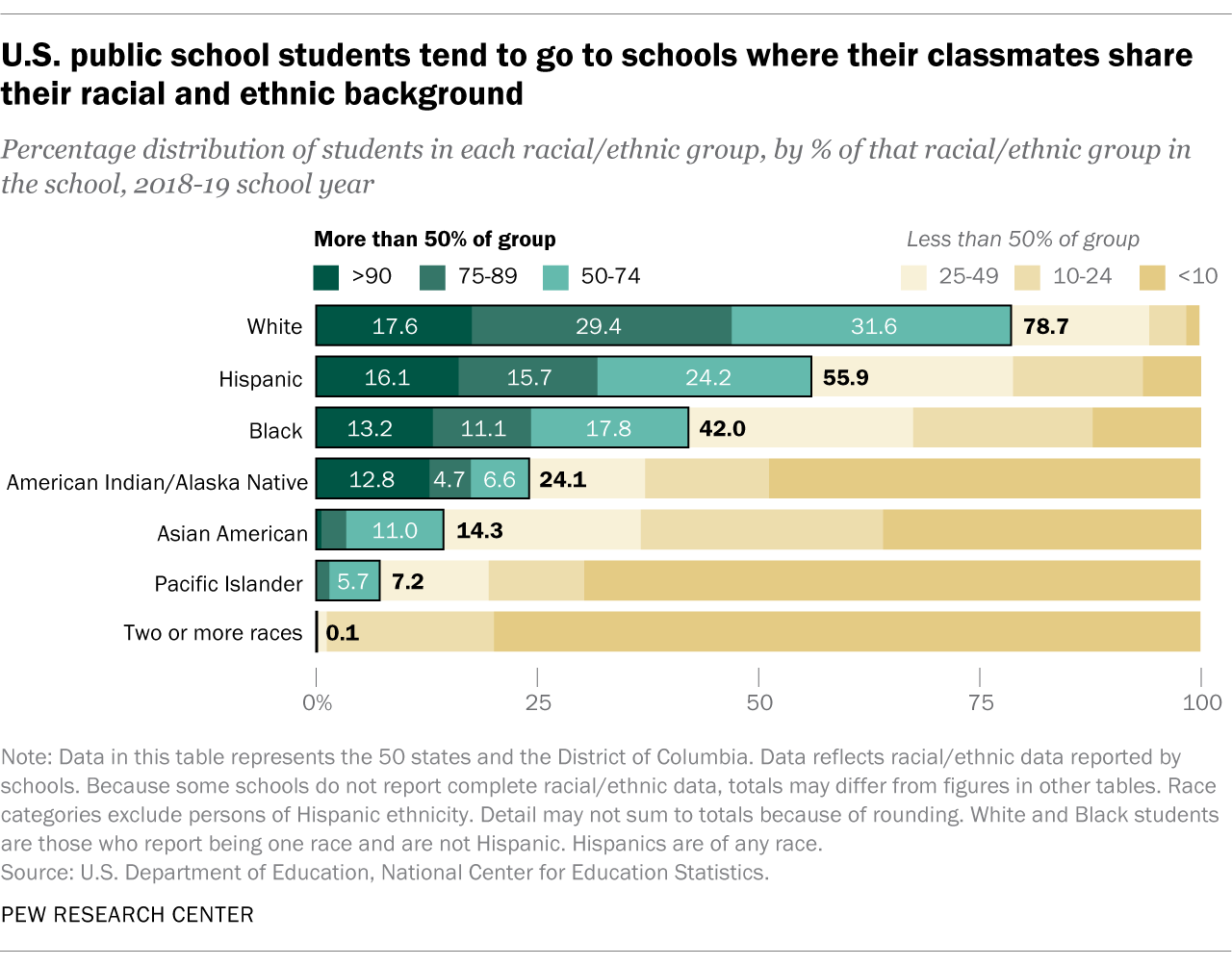

Using U.S. Department of Education data, Pew Research reports that in 2018–2019, most students attended schools that serve other students of their race and ethnicity (figure 8.24). One reason for this segregation is that we tend to live in neighborhoods that are also segregated. Rich people, who are more often white, tend to live with other rich people. Because children commonly go to schools in their own neighborhoods, the schools mirror the lack of integration in neighborhoods. While school segregation is against the law, segregated classrooms are alive and well.

Differences in educational opportunities and educational outcomes are integrally linked to school spending. Unlike many other countries, where school spending is decided by the federal government, the United States allows each state to determine its education budget and how to spend it. Although school districts may be supported by federal funds, we see significant state and local variations in student spending. Because schools are funded by each state, partially based on local property taxes, the de facto segregation of schools is caused by the segregation of housing.

Why do we have housing segregation? As we discussed in Chapter 3, structural racism and de facto housing segregation have limited access to home purchasing for people of color. For decades, Black families especially were excluded from mortgage loans through redlining and contracts woven into property deeds that prevented them from purchasing in white neighborhoods.

This legacy has made an intergenerational impact. As families are excluded from neighborhoods that provide better educational access, they have been essentially excluded from the opportunities that better education affords.

Ability, Disability, and Inclusion

In addition to prohibiting segregation based on race, ethnicity, color, and gender, federal law requires that students who are labeled as “disabled” receive equitable education and educational support. The right to equal education and other accessibility was legalized in 1990 with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) was also passed in 1990. It required that K–12 school districts provide free and appropriate education to students with disabilities (Rivera et al. 2023).

In order to ensure equitable education, schools began to integrate classrooms (figure 8.25). The term inclusion began to be used, referring to the laws and practices that require disabled students to be included in mainstream classes, not separate rooms or schools.

In one example of inclusion supported by law, the Education of All Handicapped Children Act (EHC) of 1975 included deafness as one of the categories under which children with disabilities may be eligible for special education and related services. This law required public schools to provide educational services to disabled children ages 3 to 21. This law included d/Deaf students as disabled under the law, expanding the services available to them and increasing integration.

Inclusion advocates use “d/Deaf” to distinguish between two meanings: a physical condition and a social location. The term “deaf” is the medical condition of being physically unable to hear. It reflects the perspective of medical professionals who define deafness as a medical disability needing intervention, treatment, and special support to enable deaf people to function in a hearing world. “The medical model of disability says that people are disabled by their impairments or differences” (Thierfeld Brown 2023, emphasis added). In the medical model, people suffer from deafness.

When the word “Deaf” is capitalized, on the other hand, it refers to a culturally unique group of people. According to Dr. Lissa D. Stapleton, a Deaf studies professor, “The upper-case D in the word Deaf refers to individuals who connect to Deaf cultural practices, the centrality of American Sign Language (ASL), and the history of the community” (Stapleton 2015:569).

In this idea of Deafness, Deaf communities have their own language, culture, and practices that are different from hearing cultures but just as valuable. This definition uses the social model of disability, which says that disability is caused by the way that society is organized (Thierfeld Brown 2023). This model says that a physical limit is only a problem if society doesn’t address the need. If the world were organized to support d/Deaf people and hearing people, we would not see inequality.

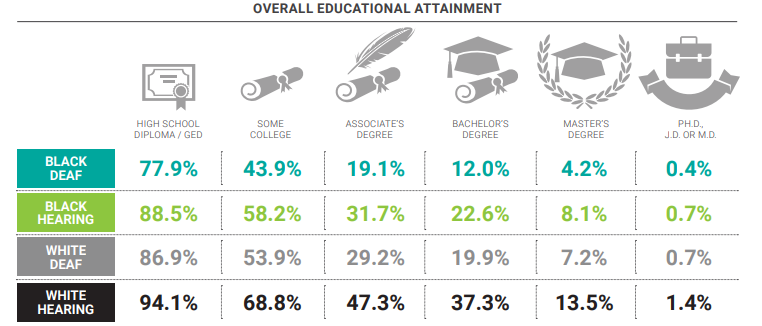

Let’s look at d/Deafness with an intersectional lens, as defined in Chapter 3. Specifically, what are the educational outcomes related to race and hearing status? The table in figure 8.26 addresses the overall educational attainment for Black Deaf, Black hearing, white Deaf, and white hearing students. It’s based on U.S. Census data from between 2008 and 2017.

Hearing people have higher educational attainments than d/Deaf people, except for the PhD, JD, or MD levels, in which Black hearing and white d/Deaf people comprise only 0.7 percent of each population that attained that level of education. Black d/Deaf people had the lowest level of educational achievement of any category.

Audism is one factor explaining the suffering in these students’ stories and the different outcomes of d/Deaf students. Audism is “the notion that one is superior based on one’s ability to hear or behave in a manner of one who hears” (Humphries 1977:12). Students who are d/Deaf experience discrimination because others assume hearing people are superior. They design the education experience with hearing people in mind. Together, audism and racism impact who learns.

Educational Debt

One of the most common ways that analysts study inequity in education is with the achievement gap: any significant and persistent disparity in academic performance or educational attainment between different groups of students. For example, gaps might be studied between white students and students of color, or students from higher-income and lower-income households (Great Schools Partnership 2013). Achievement gaps can be identified at any level of schooling, from kindergarten to high school and college.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings (figure 8.27) explores what makes the most effective teachers, with a particular focus on those who are able to close the achievement gap for Black students. During a speech in 2006, she argued that sociologists should study educational debt rather than the achievement gap.

Educational debt is the cumulative impact of directing social-political harm toward students of color, including allotting fewer resources toward their education (Ladson Billings 2006). This education debt includes a few characteristics.

The first characteristic is economic. According to Ladson-Billings, the achievement gap is problematic because it is a short-term measure, not a long-term one. Short-term measures don’t help us understand the deeper roots of the problem. Our educational debt stems from a series of long-range decisions that initially made education illegal for some and segregated for others, followed by decades of inequitable spending.

The second component of our educational debt is sociopolitical (a combination of social and political factors). For example, consider the impact that structural racism in voting arenas has on education. Black and Brown people face more tangible barriers on their way to the polls, such as transportation problems, times, and locations not conducive to their work schedules. They are also more likely to be asked to show photo ID at the polls. As people of color are excluded from voting, they are, in turn, excluded from decision-making that affects their school districts.

Finally, Ladson-Billings argues that education experiences a moral debt “that reflects the disparity between what we know and what we actually do” (Ladson-Billings 2006:8). She asks, “What is it that we might owe to citizens who historically have been excluded from social benefits and opportunities?”

She quotes Randall Robinson: “No nation can enslave a race of people for hundreds of years, set them free bedraggled and penniless, pit them, without assistance in a hostile environment, against privileged victimizers, and then reasonably expect the gap between the heirs of the two groups to narrow” (Robinson 2000 as cited in Ladson-Billings 2006:8).

Education-related policy in the United States has an extensive and elaborate history, from the exclusion of students based on race and ethnicity to the rights laws that tackled integration and access, including protections for students with disabilities. The notion of educational debt provides another framing for our education story. It avoids calling out specific groups for poor outcomes. It instead encourages us to focus, with a moral lens, on the results of unequal social and economic structures and their impact on education over time.

Going Deeper

For more on the story of educational segregation and integration, watch the video “Separate but Not Equal: The Stories Behind Brown v The Board of Education” [Streaming Video].

For more on desegregation with Latinx students, watch “Austin Revealed: Chicano Civil Rights ‘Desegregation and Education’” [Streaming Video].

For more on the Little Rock Nine, see this History.com page [Website] with a blog and video.

To hear more on Sylvia Mendez and Mendez vs Westminster, watch the video “Mendez v Westminster: Desegregating California’s Schools” [Streaming Video].

For more information on school funding, read the report Education Statistics: Facts About American Schools [Website]. At the end of the article, there is an interactive map of the United States that shows the spending per pupil for each state.

To see more maps that show redlining, see the site Mapping Inequality [Website] and this accompanying guide [Website].

For more information on racial restrictive covenants in Seattle, see this Seattle Civil Rights and History project page [Website].

To hear more about inclusion, watch “Integrating Deaf Children into a Regular Classroom” [Streaming Video].

To learn more about Gloria Ladson-Billings, read the article “Gloria Ladson-Billings: Daring to Dream in Public” [Website].

Licenses and Attributions for Policy Matters for Social Justice

Open Content, Original

“Policy Matters for Social Justice” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Images 8.20-8.23 and 8.25 added by Aimee Samara Krouskop.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 8.20. “Mural by Wayne Rafiki Morris” is on Flickr, by art around and licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 8.21. “Sylvia Mendez” is published by the Zinn Education Project and is in the public domain (left). “Mural created by Orange County, California students” is in the public domain (right).

Figure 8.22. “Operation Arkansas, Little Rock Nine” is on Wikipedia, by the U.S. Army, and in the public domain (left). “Hazel Bryan yelling at Elizabeth Eckford” is on Wikipedia, by Will Counts, and in the public domain (right).

Figure 8.23. “Button from Washington DC Freedom March” from the Smithsonian National Museum is included under CC0 (left). “Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Addresses a Crowd” is on Wikipedia by Public Affairs Office and is in the public domain (right).

“De Facto Segregation” includes adapted content from “De Facto Segregation” in Creating Under-resourced Communities: Racism, Segregation, Redlining in Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice by Nora Karena, originally in “Finding a Home: Inequities” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Carla Medel, Katherine Hemlock, and Shonna Dempsey, Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 1e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Nora Karena, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include adding new content about structural racism to redlining. Modifications by Kimberly Puttman, licensed under CC BY 4.0, apply the concept of redlining to education.

Figure 8.25. “Rising Children” by Carol M. Highsmith is on Flickr, shared by GPA Photo Archive and licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

“Ability, Disability, and Inclusion” and “Education Debt” include adapted content from “Education as a Social Problem” by Kimberly Puttman, in Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Significantly edited to apply a social change lens.

Figure 8.26. “Overall Educational Attainment” from Postsecondary Achievement of Black Deaf People in the United States (p. 12) by Carrie Lou Garberoglio, Lissa D. Stapleton, Jeffrey Levi Palmer, Laurene Simms, Stephanie Cawthon, and Adam Sale, published by the National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes, is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.24. “U.S. Public School Students Tend to Go to Schools Where Their Classmates Share Their Racial and Ethnic Background” from “U.S. Public School Students Often Go to Schools Where at Least Half of Their Peers Are the Same Race Or Ethnicity” by Katherine Schaeffer and Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C., is licensed under the Center’s Terms of Use.

Figure 8.27. “Image of Gloria Ladson-Billings” by Marcus Miles, published in “Gloria Ladson-Billings: Daring to Dream in Public” by Käri Knutson, University of Wisconsin-Madison, is included under fair use.

the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that a society needs.

a state where "everyone has fair access to the resources and opportunities to develop their full capacities, and everyone is welcome to participate democratically with others to mutually shape social policies and institutions that govern civic life.”

large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society.

the social position an individual holds within their society. It is based upon social characteristics of social class, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, and religion and other characteristics that society deems important.

a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior.

the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions.

the systemic and extensive nature of social inequity and harm woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness.

the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group.

a policy or system of segregation or discrimination on grounds of race

the financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions.

figures, extents, or amounts of phenomena that we are investigating.

the way human interactions and relationships transform cultural and social institutions over time.

segregation that occurs without laws but because of other social influences.

the system of racial bias that exists across institutions and society.

the discriminatory practice of refusing loans to creditworthy applicants in neighborhoods that banks deem undesirable.

the laws and practices that requires disabled students be included in mainstream classes - not separate rooms or schools.

a group of people that share relationships, experiences, and a sense of meaning and belonging.

the shared beliefs, values, and practices in a group or society. It includes symbols, language, and artifacts.

differences in access to resources or opportunity between groups that are the result of treatment by a more powerful group; this creates circumstances that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair.

any significant and persistent disparity in academic performance or educational attainment between groups of students with different social locations.

the cumulative impact of directing social-political harm toward students of color, including allotting fewer resources toward their education.

a Christian concept for work that is assigned to a person by God and that provides meaning and purpose to a person’s life.