7.3 Inequality in Belonging

Kimberly Puttman

We have already started seeing how inequality in belonging relates to families. Let’s look deeper at citizenship, ethnicity, and sexual orientation to see how these social locations impact belonging.

Early Roots: Slavery, Bodily Autonomy, Citizenship and Class

In the first part of this book, we’ve examined how class, race, gender, sexual orientation and ability/disability shape the experiences of social problems. As we look deeper, we see that a powerful connection exists between slavery, bodily autonomy, citizenship, and class.

In the early years of our country’s founding, wealthy White immigrants wanted to maintain their wealth and social standing. In the North, many of these wealthy owners became mill or manufacturing businessmen. In the South, many of these wealthy owners owned land, growing cotton, tobacco, and sugar. These crops were labor intensive and needed abundant cheap labor to ensure profit. White enslavers enslaved Black Africans to do the work in forced labor camps (plantations). Northern manufacturers also benefited from slavery because their mills used cotton and other southern crops to create cloth and blankets they sold.

To ensure that they made money, enslavers enforced a system that stripped enslaved people of their bodily autonomy. Bodily autonomy is the idea that a person has the power to decide what happens to their own body (Artim N.d.). Part of the definition of slavery is that an enslaved person is denied their bodily autonomy by an enslaver. Enslaved people could not choose where they worked or what they ate. They could not get married (Berry 2018). Enslavers could harm or kill enslaved people for any reason without any legal retribution.

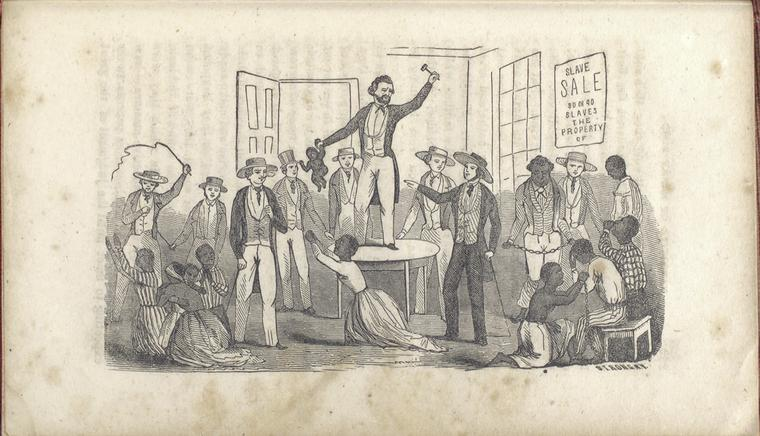

While these restrictions were horrific for any enslaved person, women faced additional challenges to their bodily autonomy. Enslavers could rape them at any time. Their children could be sold for any reason, as depicted in the illustration in Figure 7.8, showing a Black child being sold at auction, with their mother pleading to stop the sale.

Beyond the individual experience of violence, enslavers codified new rules about children and race. Reversing centuries of English law, which said that any child belongs to the father’s family, colonists enacted laws that said children belonged to the mother. In 1662, the Virginia colonists passed a policy which read:

Whereas some doubts have arrisen (sic) whether children got by any Englisman upon a Negro woman should be slave or ffree (sic), Be it therefore enacted and declared by this present grand assembly, that all children borne (sic) in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother. (Roberts 2021:50)

Not only were the children of a White man and a Black woman considered Black, but the children were also enslaved at the moment of their birth.

Dorothy Roberts, a professor of law, sociology, and Africana studies, writes that the laws that created our current racial classification system regulated interracial sex. She writes,

Though these laws were partly aimed at presenting miscegenation [the mixing of races], they also incentivized the rape of Black women by their white enslavers, who could profit from their sexual assaults by enslaving any resulting children (Roberts 2021:48).

This lack of bodily autonomy had even more consequences. For example, enslaved people were not citizens of the new country of the United States. However, free White persons who had lived in the United States for two years and were “of good character” could become citizens (Blakemore 2020). In addition, White children who were born in the United States could become citizens.

This concept of birthright citizenship means that a child born in a country becomes a citizen, regardless of the citizenship of their parents. This concept was powerful for a new country, because it began to allow the formation of an American identity. Citizenship allowed people to vote and to run for public office. Citizens must pay taxes to support the government, but they also receive public benefits. Today, some of the public benefits are Social Security and Medicare. Even though birthright citizenship is a powerful concept, it didn’t apply to everyone when it was initially established.

In 1790, Black people were over 20% of the US population and over 40% of the population in Southern states (Bouton 2010). In order to maintain White supremacy, White people did not grant birthright citizenship to enslaved people. Only the 14th amendment, which was ratified after the Civil War, offered birthright citizenship to all Black people born here.

Today, slavery is illegal, and Black people have full citizenship, but the historical oppression that is tangled in capitalism, patriarchy, racism, and citizenship continues to harm people today. For example, Black families continue to experience more housing instability than White families, a problem we explored in Chapter 6.

The Intersectionality of Belonging: Ethnicity, Origin, and Citizenship

Where do you come from? Where do you belong?

On the surface, these questions may sound simple. You might answer that your family comes from Ireland, and you belong right here, in your hometown. Or your answers may be much more complicated. Your parents are from Honduras, but you are American. Your family was here before the United States was formed, either because your family is Indigenous or descended from the Spanish and Portuguese that colonized in the 1500s and 1600s. These answers are as complex and nuanced as each one of us is different.

However, the government regulates who gets to belong in a country, state, or community. They decide who gets to be a citizen and who gets to be a family. As we demonstrated in Early Roots: Slavery, Bodily Autonomy, Race, and Class, race determined citizenship historically, and continues to influence belonging today. What other factors can influence citizenship and belonging?

Ethnicity

Jewish, Irish, Latinx. What do all these groups have in common? It’s not a country. Every group shares a country with another group or is found in multiple countries. It’s not religion, although Jewish is also a religious tradition. It’s not race because Irish and Latino people, for example, may be from many different races.

The commonality is that each of these groups shares a unique ethnicity. As you will remember from Chapter 2, ethnicity is a group of people who share a cultural background such as language, location, and religion. Often these groups share behaviors or cultural practices also.

For example, people who identify as Jewish may practice the Jewish religion. According to devout Jews, children are Jewish if their mothers are Jewish. Almost 30% of Jewish people in the US identify as Jewish but don’t practice Judaism as a religion (Pew Research Center 2021). They may still enjoy latkes as holiday food but not celebrate Shabbat regularly.

Irish is yet another ethnic group, as shown in Figure 7.12. Over five million people live in Ireland as of 2023. They are Irish as their ethnicity and their nationality. However, more Irish people live outside of Ireland than in the country (Haynie 2016). Their ethnicity is Irish, but not their nationality. Some people speak Irish. Others say they are Irish because their grandparents or great-grandparents emigrated from there. Still others learn Irish step dancing or storytelling or the harp and pennywhistle. Many are Catholic. Some are Protestant. People in Ireland and around the world identify as Irish ethnicity.

But how does ethnicity impact the social problem of belonging and family? Fundamentally, ethnicity can be a social location that experiences oppression and privilege. Let’s look at some examples.

First, ethnic groups often experience violence related to their ethnicity. More than 60% of all European Jews were murdered during the Holocaust in World War II (The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum N.d.).

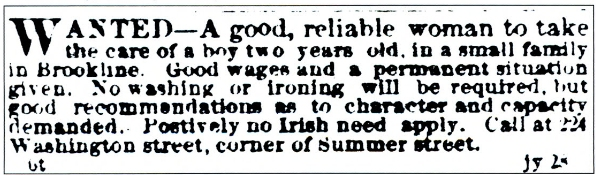

Even when violence is no longer a response, people from different ethnic groups may experience oppression. For example, the advertisement in Figure 7.13 notes that no Irish need apply. Although academics debate how many of these signs were actually posted, there was widespread anti-Irish prejudice and discrimination in the mid-19th century immigration to the United States. Irish immigrants fought to redefine these laws, policies, and practices. Now, most people of Irish ethnicity define themselves as White.

Unpacking Oppression, Naming Justice: Why is Latinx a Word?

“Like other racial and ethnic terms in this country, “Latino” and “Hispanic” were created as counterpoints to “white.”…”White” was invented five hundred years ago to describe the privilege enjoyed by one group of people, and to justify the exploitation of “Black” people. In the words of James Baldwin, “White is a metaphor for power.”

…It strikes me how “Latino” is a shield of unity that protects our people, and that gives them a common sense of purpose, in this unraveling country we call home.

—Héctor Tobar, Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of “Latino”

You may have heard the words Hispanic, Latino, Mesoamerican, Chicano, Chicana, or Latinx to refer to people who share an ethnicity. One of the first questions that White people often ask Brown-skinned people is, “Where are you from?” (Sue et al. 2007), followed closely by “What should I call you?”

Although the terms Hispanic and Latino are often used interchangeably, they are not the same, as shown in the Figure 7.14. Hispanic usually refers to native speakers of Spanish. Latino refers to people who come from, or whose ancestors came from, Latin America. Not all Hispanics are Latinos. Latinos may be of any race or ethnicity; they may be of European, African, Native American descent, or mixed ethnic background. Thus, people from Spain are Hispanic but are not Latino.

One of the reasons some people prefer Latino is that it focuses on Latin America. It excludes Spain, the country that colonized much of Latin America. Many Mesoamerican people identify with the country of origin of themselves or their families. Origin refers to the geographical location where a person was born and grew up. This includes regions of the United States, as well as other countries. In immigrant families, children may call themselves Mexican American or Puerto Rican if their families originated from those countries.

One of the emerging terms is Latinx. Latinx is used as a gender-neutral alternative to Latino or Latina. Similarly to they/them pronouns, Latinx does not imply or impose gender identity on the people who label themselves that way. Latinx is an invitation to queer people, an acknowledgment that people who are gender non-conforming exist with the intersqueernal identities of Latin o/a and queer.

Now it’s your turn to unpack oppression and name justice:

From the following list of options for this activity, please select about 5 minutes’ worth of content.

- Hispanic, Latino, Latinx: What Is In a Name [Streaming Video] This 3:11-minute video describes the experiences of community members around naming.

- Key Facts about US Latinos and Their Diverse Heritage[Website] This research article from Pew Research examines the Diversity of US Latinos.

- What Being Hispanic and Latinx Means in the United States [Streaming Video] In this 11:51 Ted Talk, student Fernanda Ponce talks about racism and being Latinx in the United States.

- John Leguizamo discusses Latinx [Streaming Video]

This 1:18-minute TikTok video shows actor John Leguizamo talking about the term Latinx with popular artists. - Hanging with the Oregon Homies, episode #2 [podcast] This podcast is from Dr. Franki Trujillo Dalbey and Dr. Oscar Juarez, recorded in Oregon. In it, they discuss all the variations of names. Although they changed their mind later about Latinx based on John Leguizamo’s work, it remains a fascinating discussion of the power of naming. It’s 29 minutes long, but you can listen to a shorter snippet.

Once you’ve watched, read, or listened, please consider these questions:

- How can we see naming as a process of social construction?

- How does naming convey power?

- How is “Where are you from?” a racist statement when asked by a White person to a person of color? Could “Where are you from?” be a useful question between Mesoamerican people?

- How can naming start to solve a social problem?

Citizenship and Ethnicity

The importance of ethnicity only begins with naming. Ethnicity is part of how White people in power define who belongs in our society and who doesn’t. Let’s look at how ethnicity and citizenship are connected.

Most Latinx people who live in the United States are citizens. As of 2019, two-thirds of all Latinx people were born in the United States. They have birthright citizenship. Only one-third of the Latinx population are immigrants. As more children are born in the US, the percentage of the Latinx population who are immigrants decreases. Most Latinx immigrants immigrate legally.

Undocumented people are anyone residing in any given country without legal documentation. It includes people who entered the US without inspection and proper permission from the government and those who entered with a legal visa that is no longer valid (Immigrants Rising 2023). Only approximately 12% of Latinx people in the US are undocumented. This is a much smaller number than many politicians would have you believe.

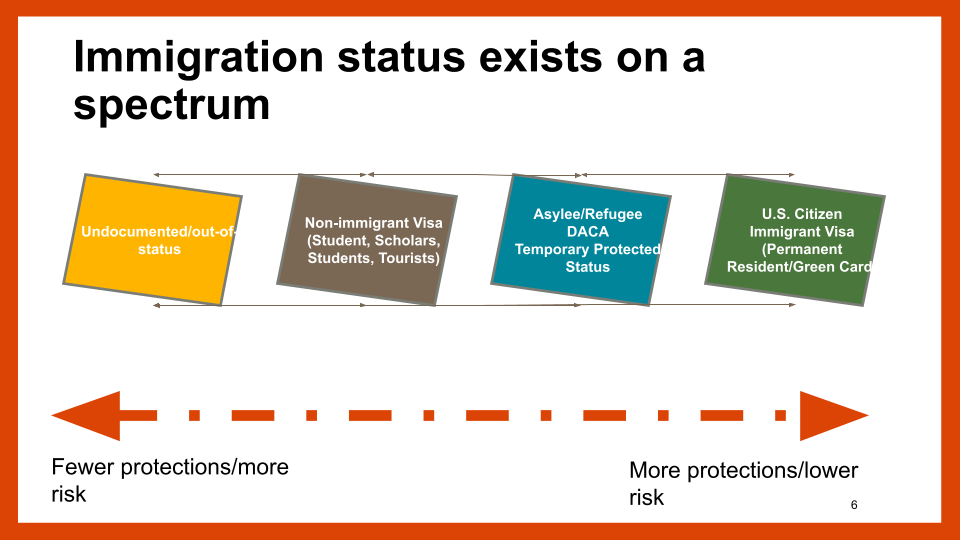

The binary of documented and undocumented hides a more complicated truth. Immigration exists on a spectrum. Many families are mixed-status families.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FmfzfjrIPoo

A mixed-status family is a family whose members include people with different citizenship or immigration statuses, as shown in Figure 7.15. Please take a few minutes to learn about the experiences of mixed-status families by watching the video in Figure 7.16. One example of a mixed-status family is one in which the parents are undocumented, and the children are US-born citizens. The number of mixed-status families is growing. Between 2010 and 2019, the number of children aged 17 and under with immigrant parents grew by 5%. As of 2019, more than a quarter of young children in the United States were children of immigrants, and nearly 90 percent of these children were US citizens (National Immigration Law Center 2022).

One place we see social problems at work for immigrant families is when we look at mixed-status families. Mixed-status families experience social, economic, legal, and health challenges unique to their family configuration. These families are often multigenerational extended families with grandparents, parents, and children in the same house.

Let’s learn about another mixed-status family.

Another immigrant story: My Mom

My mom came to the United States accompanied by her aunt and uncle at the age of 14. She and her parents (my grandparents) decided that it would be best for her to leave Mexico because she was no longer attending school, as they could not afford it, and she was more than likely going to be stuck working at my grandpa’s small farm for the rest of her life.

Once in the United States, she was able to return to school and soon became the first in the family to graduate from high school. She found it impossible to further her education as there were no scholarships or loans available to undocumented folks at the time, so she went to work. She worked at a potato factory, met my dad, and had kids, including me. Right around this time, DACA came around, which was huge. She applied for DACA, was approved, and soon after was able to quit her factory job for a much better-paying job.

Now that myself and my siblings are a little older, she is considering going back to school and even buying a house, but she finds herself constantly second-guessing that decision as her future here in the United States is uncertain.

Now that we understand a little bit about specific families’ experiences, we can look more deeply at the laws and policies that impact them. These laws and policies include DACA and the Dream Act.

DACA, Dreamers, and Immigration

Carla Mendel is a Latinx woman and daughter of immigrants. She was a community college student when she wrote this section, perhaps similar to you. She wrote this content about DACA and Dreamers as an open pedagogy project for Open Oregon, the project we described in Chapter 5. This section has been updated slightly to include more current data.

DACA

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) is a policy created under the Obama administration on June 15, 2012. Key criteria for DACA eligibility are:

- are under 31 years of age as of June 15, 2012

- came to the US while under the age of 16

- have continuously resided in the US from June 15, 2007, to the present

- More criteria are listed at the US Citizenship and Immigration DACA Website. You can read more if you are interested.

An applicant granted DACA is not considered to have legal status but will not be deemed to be accruing unlawful presence in the US during the time period when their DACA is in effect. DACA allows individuals to live in the US without fear of deportation and with work authorization. DACA is temporary. Every two years the individual will need to reapply, which means submitting an application, getting biometrics done, and paying a fee of $495.

At its peak, there were up to about 800,000 DACA recipients, but those numbers dramatically declined during the Trump Administration due to fear of what would happen to the DACA program. The number of people on DACA now is closer to 600,000.

As of 2023, DACA is still legal but being contested. The Fifth Circuit court, which includes Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, ruled that DACA is illegal, so new DACA applications are being accepted but not processed. However, people who are on DACA today can reapply (US Citizenship and Immigration Service 2023).

DREAM Act

The Dream Act, which would make DACA permanent and would give DREAMers an opportunity to obtain legal status if they meet the requirements. The US House has passed this bill, but not the Senate. President Joe Biden has promised to sign it if it passes Congress (Gogol 2023).

The DREAM Act would create a conditional permanent resident status valid for up to eight years for young undocumented immigrants. It would protect them from deportation, allow them to work legally in the United States, and permit them to travel outside the country. It would also allow them to become permanent lawful residents. Having a clear path to lawful resident status allows DREAMers to belong.

The Legal Process

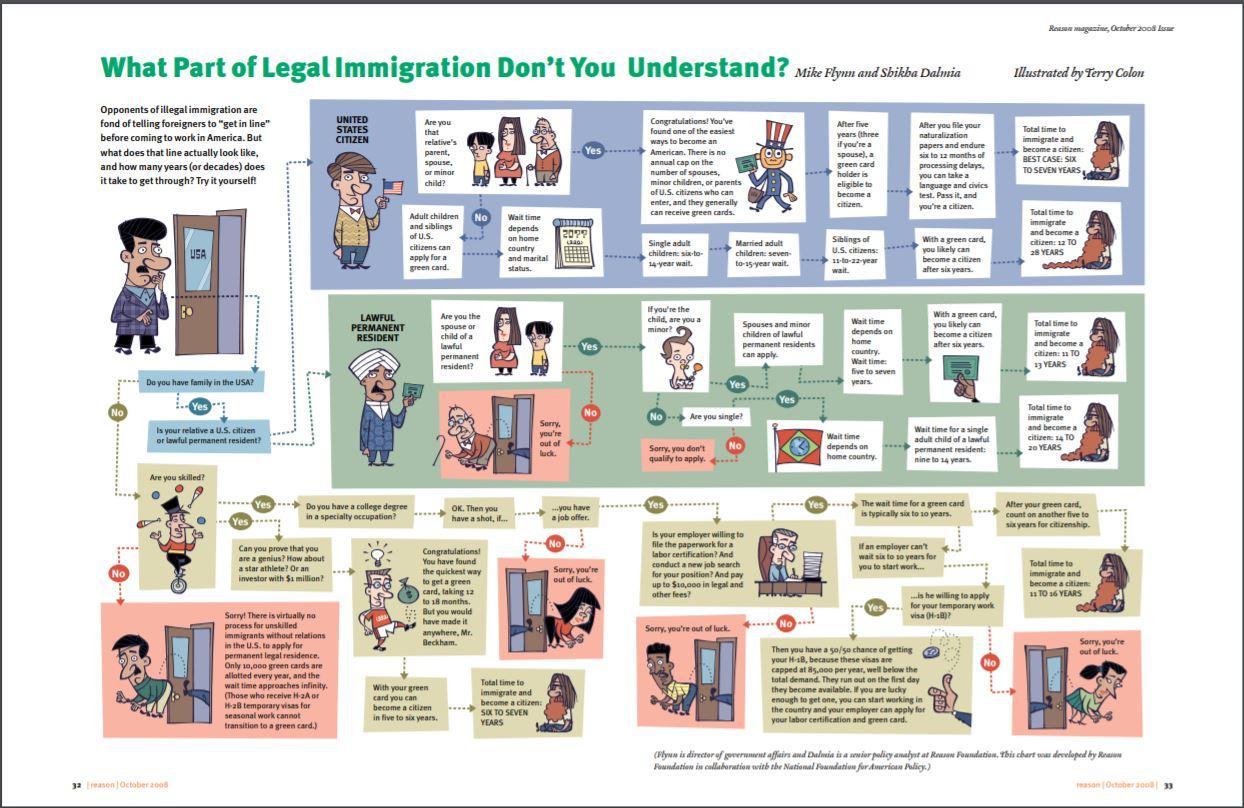

“Just come here legally,” is one of my most disliked phrases for immigrants because the process to do so is not as easy as the general public thinks, as shown in Figure 7.17. Immigrants, just like everyone else, move because where they currently are isn’t providing them what is needed to succeed. Unlike here in the United States, they cannot just move from one state to another to seek out those opportunities, as they do not exist there either. Instead, they need to leave the country.

Some people have the time and money needed to try and apply for a visa or have a family member who is a United States citizen or legal permanent resident (LPR) sponsor them to become an LPR and can come to the United States that way. This could take anywhere from six to 28 years and will cost anywhere from $750 to $1,225 per person (US Citizenship and Immigration Services 2022), so it’s obvious that there could be a lack of money needed to take this route. It is even worse for others if their current situation might be more urgent, and they don’t have the time to wait. If legal immigration was easy, accessible, and fast, it’s very unlikely that people wouldn’t risk their lives entering and living in the United States without documentation.

Government control of immigrant families goes beyond courts and laws. It also includes breaking families apart. Resistance to this action is shown in Figure 7.18. The US government forcibly separated 5,000 children from their families in 2017 and 2018. In the application of this “Zero-tolerance” policy, undocumented parents were deported. Because children can’t be imprisoned, they were handed over to the Department of Health and Human Services. These children were cared for in refugee resettlement shelters. However, cared for isn’t the right word. They were held in cages. Some caretakers raped or assaulted the children. Some children died because of illness and neglect. Ex-president Donald Trump rescinded the zero tolerance policy as of June 2018, but separations continued to occur. As of November 2021, 2248 children had been reunited with their families. The remainder have not been reunited (Southern Poverty Law Center 2022).

As of 2023, the work of reuniting families continues. Some sources estimate that 1,000 children still need to be reconnected with their families. Some children haven’t seen their families in five years. The trauma that families experienced in their home countries and the trauma they experienced during forced separation continues. Unsurprisingly, a recent study finds that parents and children who have been separated need significant mental health support even after family reunification occurs (Hampton et al. 2021).

These challenges to immigration and the political rhetoric that supports limiting immigration is based on a particular kind of prejudice known as nativism. Nativism is an intense opposition to an internal minority that is seen as a national threat on the grounds of its foreignness (Kešić and Duyvendak 2019:445). For example, the political slogan, “Make America Great Again” is partially based on the idea that there is something wrong or dangerous with immigrants so therefore, immigration should be restricted. Nativism is an underlying cause of the inequality that immigrant families face.

Queer Families

Families challenged by immigration and citizenship are not the only kinds of families that experience inequality in the United States. Queer families also experience inequality. Approximately 3.3 million people live in same-sex marriages and partnerships. This number is growing. However, these families experience social, economic, and legal challenges. Before we look at the experience of these families, let’s examine this unique word: queer.

Unpacking Oppression and Queering Justice: What Do I Mean When I Say Queer?

For some people, queer is a bad word. For others, it is a source of power. Please take a moment to watch the 3-minute video in Figure 7.19 from activist Tyler Ford about the history of the word queer. How do you understand this word?

I, Kim Puttman, call myself queer. Queer as in different, but also queer as in challenging dominant ideas about what identity, sexuality, love, relationship, and family look like. I also identify as lesbian. I love my wife. Our relationship expands what it means to be “normal” and “healthy.” I embrace this identity as a source of my power, even though it is also a source of my marginalization. I stand with generations of activists before me, chanting, “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it!” In the words of Alex Kapitan on the Radical Copy Editor blog:

In its simplest form, queer means upending mainstream norms about sexuality and gender (particularly the ones that say that being straight is the human default and that gender and sexuality are hardwired, binary, and fixed rather than socially constructed, infinite, and fluid). It also usually speaks to solidarity across lines of race, class, dis/ability, gender, sexuality, and other identities as part of a radical politics of transforming the status quo and working toward collective liberation. (Kapitan 2021)

But queer can also be used as a word that conveys hate. When used as an insult, queer is a word that wounds. Using this word as a threat may be grounded in homophobia, the irrational fear of or prejudice against individuals who are or are perceived to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual people. More importantly, it maintains heteronormativity, the assumption that heterosexuality is the standard for defining normal sexual behavior and that male–female differences and gender roles are the natural and immutable essentials in normal human relations (APA 2023). When a bully calls someone queer, they reinforce the idea that being straight and cisgender is the only right way to be.

So, in this murky terrain, which word do you use? Figure 7.20 offers an illustration that may help:

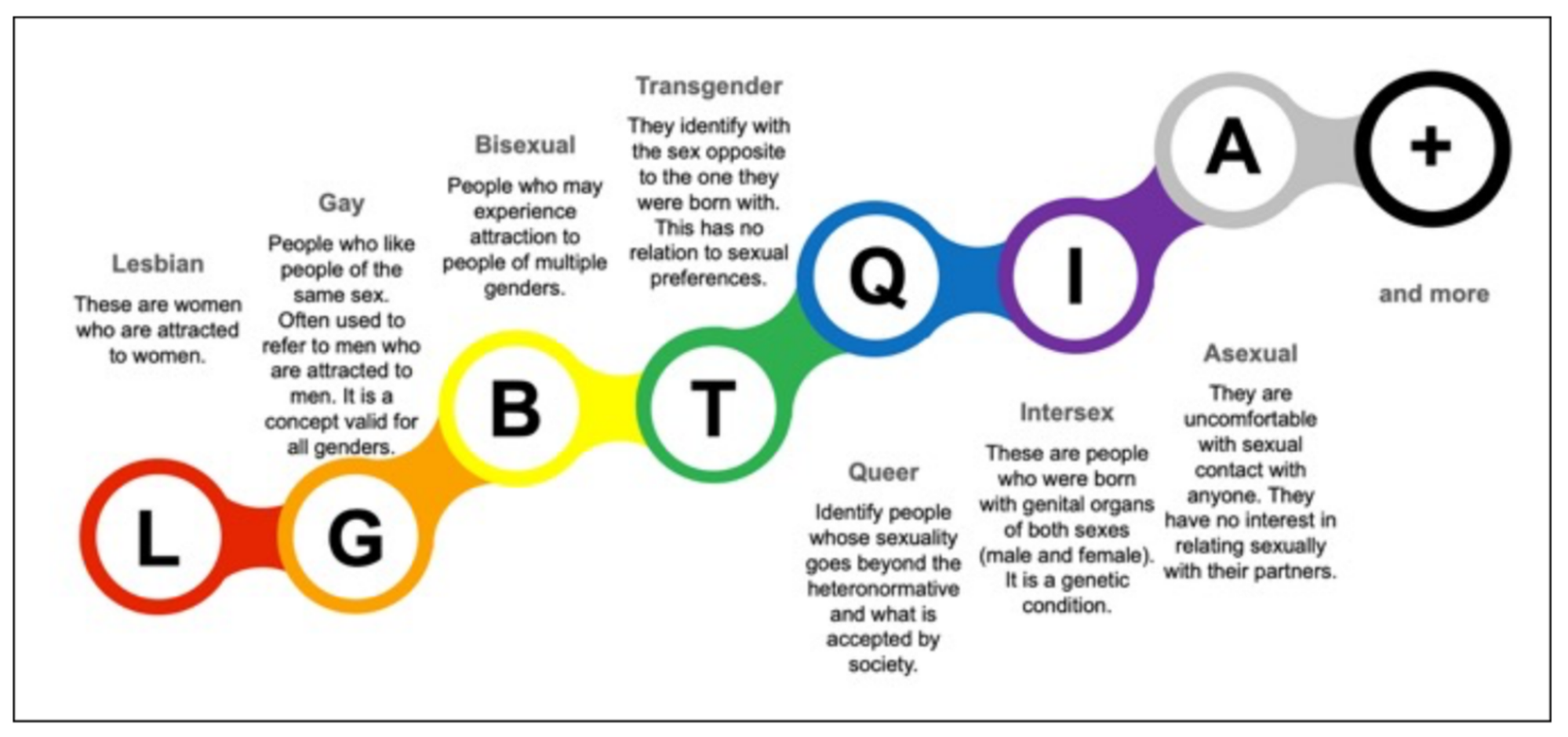

Although there are many historical reasons that certain names are preferred, it can help to understand that we are looking at continuums of gender and sexual identity. We won’t repeat the dictionary, but you can look for specific definitions of the terms below in the Human Rights Campaign glossary and the Outright International Terminology Blog if you want more detail. The following categories provide an entry point into this discussion about how people describe themselves:

- Anatomical Sex: Some of these words describe the sexual characteristics of your physical body. These words include female, male, and intersex.

- Gender Identity: Some of these words are used to explore whether your physical body and your identity about your physical body match. These words include cisgender and transgender. They can also include male and female, when your identity and your sex match. Want to learn more? In Trans 101 – The Basics [YouTube Video] by Minus18, students describe transgender identities and pronouns

- Gender Expression: Some of these words refer to someone’s gender or outward expression of gender. These words include androgynous, feminine, or masculine.

- Sexual Attraction: Some of these words refer to someone’s sexual attraction—do they love someone of the same gender, a different gender, or without reference to gender. These words can include lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual, and many others.

- Culturally Specific Language: Finally, some of these words describe cultural experiences of non-conforming sexuality or gender identities. These words include Two Spirit, Muxes, and many more. For more, check out these resources: What Does “Two-Spirit” Mean? [YouTube Video] in which “two-spirit” is described by a two-spirit person, and the blog post, Beyond Gender: Indigenous Perspectives Muxe

But, wait, what’s the answer? Can I call someone queer? Maybe, maybe not…

My advice is to listen first. If you listen to what people call themselves, you will use the right word, whether queer, lesbian, they, trans, or just me.

What do you think?

Now it’s your turn to unpack oppression and queer justice:

If this is the first time you’ve considered these concepts, they can be kind of confusing. To help, activists created a “gender unicorn” as a way of sorting out identity and attraction.

Please take a moment to look at the Gender Unicorn and figure out where you fit on the continuums. If you aren’t sure, no problem. We usually get clearer about these identities over time.

Then consider:

- How might you experience power and privilege related to these identities?

- How might differences in these identities create belonging or damage it?

Inequality in Queer Families

It is difficult to quantify how many people in the United States are in LGBTQIA+ relationships and the number who are parenting. US Census data gives us some idea, although the numbers are likely underreported. The US census counted approximately 10.7 million adults (4.3 percent of the LGBTQIA+ population) who identify as LGBTQIA+ and 1.4 million adults (0.6 percent of the US adult population) who identify as transgender. Of those, approximately 1.1 million are in same-sex marriages, and 1.2 million are part of an unmarried same-sex relationship).

| Same-Sex Marriages | Unmarried Same-Sex Relationship | Opposite-Sex Couples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of people in Relationship Type | 1.1 million | 1.2 million | – |

| Percent Of Couples Raising Children | 31% | 31% | 43% |

As shown in Figure 7.22, 31 percent of same-sex couples, both married and partnered, are raising children, not too different from the 43 percent of opposite-sex couples also raising children (US Census 2022). Approximately 48 percent of LGBTQIA+ women and 20 percent of LGBTQIA+ men under age fifty are raising children. Approximately 3.7 million children in the United States have a parent who is LGBTQIA+. LGBTQIA+ couples are also more likely to adopt or foster children or be step-parents (US Census Bureau 2022).

Just describing the demographics of LGBTQIA+ families and parenting is only one small step in describing the inequality these families’ experience. What differences do we see?

Much of the literature on same-sex relationship quality focuses on comparing LGBTQIA+ people’s relationships with the heterosexual norm. This work has repeatedly found that LGBTQIA+ relationships experience the same satisfaction level compared to non-LGBTQIA+ relationships, The outcome of this research has shown repeatedly that LGBTQIA+ relationships are just as well adjusted as their heterosexual counterparts and experience similar stressors. With marriage equality, the recognition of same-sex marriage as a human and civil right, as well as recognition by law and support of societal institutions, queer families now face less legal discrimination. Furthermore, in an analysis of 81 parenting studies, sociologists found no quantifiable data to support the notion that opposite-sex parenting is any better than same-sex parenting. Children of lesbian couples, however, were shown to have slightly lower rates of behavioral problems and higher rates of self-esteem (Biblarz and Stacey 2010).

However, LGBTQIA+ families experience homophobia. This stress provides unique challenges for LGBTQIA+ families compared with their straight and cisgender counterparts. LGBTQIA+ couples often have to navigate judgment and rejection from their family of origin, the family into which one is born. They also may face prejudice from institutions like employment and religion.

In addition, LGBTQIA+ parents experience discrimination in child custody cases. Heterosexual parents are often favored in custody disputes with LGBTQIA+ parents (Haney-Caron and Heilbrun 2014). Prejudicial attitudes and stereotypes describing unfit lesbian moms and irresponsible gay dads have historically been used in custody cases to justify punitive court decisions. However, psychologist Charlotte Patterson studies the health of children parented in same-sex couples. She finds that it’s not the homosexuality or heterosexuality of the parents that matter. Instead, the quality of the family relationships is the most important predictor of healthy children (Patterson 2009). LGBTQIA+ families’ lives are shaped by the powerful social forces of heterosexism and cissexism.

Laws and policies related to adoption rights and foster care often discriminate against LGBTQIA+ parents. Twenty-eight states ban discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity for foster and adoptive parents. An additional four states ban discrimination based on sexual orientation. Thirteen states explicitly allow child welfare agencies to refuse services to LGBTQIA+ children and families if it conflicts with their religious beliefs. The remaining 18 states are largely silent on the topic, opening up a range of treatment toward same-sex adopting families, from active discrimination based on the law to indifference (Movement Advancement Project 2023).

Although protections for same-sex adoptive and foster parents are increasing, many LGBTQIA+ parents experience discrimination despite the overwhelming evidence that being raised in an LGBTQIA+ family is not inherently harmful or destructive to the children (Goldberg 2010; Golombok and Badger 2010; Pawelski et al. 2006).

Licenses and Attributions for Inequality in Belonging

Open Content, Original

“Inequality in Belonging” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.14. “Latino vs. Hispanic Infographic” by Kimberly Puttman and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Map image: “Latin America (orthographic projection)” by Heraldry is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Another Immigrant Story: My Mom” from “Governmental Influences on Union Formation” by Anonymous, Contemporary Families in the U.S.: An Equity Lens 2e [manuscript in press], is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

“DACA, Dreamers, and Immigration” is adapted from “Real Laws, Real Families” by Carla Medel, Contemporary Families in the U.S.: An Equity Lens 2e [manuscript in press], which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Inequality in Queer Families” is adapted from “What Is Family” by Heidi Esbensen, Sociology of Gender: An Equity Lens [manuscript in press], Open Oregon Educational Resources, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 and includes some content adapted from “LGBTQ+ Relationships and Families” by Sarah R. Young and Sean G. Massey, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications include editing for brevity and focus on social problems.

“Origin” definition from Contemporary Families in the U.S.: An Equity Lens 2e [manuscript in press] by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.8. “Slave Auction” by Henry Bibb is in the Public Domain. Courtesy of Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Figure 7.10 “Event honorees – Rachel Sklar, Bel Kaufman, Rachel Cohen Gerrol” by Jewish Women’s Archive is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Western Wall, Jerusalem” by yeowatzup is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 7.11. “Photo of Couple Making Latkes” by Rachel Barenblat is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Figure 7.12. “Musicans playing traditional Irish music” by Barbara Slavin is licensed under CC BY-NC-2.0.

Figure 7.13. “No Irish need apply” by Unknown Author, Wikipedia is in the Public Domain.

Figure 7.15. “Immigration Status Exists on a Spectrum” by Monica Olvera from Open Education for Equity (slide 30) is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.18. “Two children sit on ground holding placards” by Samantha Sophia is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 7.20. “LGBTQIA+ acronym” from “LGBTQIA+ Deconstructed” by Harold Tinoco-Giraldo, Eva M Torrecilla Sánchez, and Francisco García-Peñalvo is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.21. “Parents” by Caitlin Childs is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 7.22. “Same Sex Marriages and Relationships” by Heidi Esbensen, Sociology of Gender: An Equity Lens [manuscript in press] is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 7.9. “Photo” of Dorothy Roberts © University of Pennsylvania is included under fair use.

Figure 7.16. “Mixed Status Family” by Cities for Action is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 7.17. “The Legal Process” © Terry Colon, Mike Flynn, Shikha Dalmia, Reason Magazine is included under fair use.

Figure 7.19. “Tyler Ford Explains The History Behind the Word ‘Queer’” by Tyler Ford is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 7.23. “Photo” from “VOTING DAY: Questions and clarity on SOGI 123 in Abbotsford” by Dustin Godfrey, Abbotsford News is included under fair use.

a group of people who share a cultural background, including language, location, or religion.

a person’s emotional, romantic, erotic, and spiritual attractions toward another person

a group who shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation

a socially constructed category with political, social, and cultural consequences, based on incorrect distinctions of physical difference

a social expression of a person’s sexual identity that influences the status, roles, and norms of their behavior.

a disability is a condition of the body or mind which makes it more difficult for a person to participate fully in everyday life

the idea that a person has the power to decide what happens to their own body

the total amount of money and assets an individual or group owns

the ability of an actor to sway the actions of another actor or actors, even against resistance

the systematic study of society and social interactions to understand individuals, groups, and institutions through data collection and analysis.

a biological categorization based on characteristics that distinguish between female and male based on primary sex characteristics present at birth.

an economic system based on private ownership and the production of profit.

a form of mental, social, spiritual, economic and political organization/structuring of society produced by the gradual institutionalization of sexbased political relations created, maintained and reinforced by different institutions linked closely together to achieve consensus on the lesser value of women and their roles.

a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produces and normalizes racial inequities

a personal or institutional system of beliefs, practices, and values relating to the cosmos and supernatural.

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world

the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location that define an individual or group in relationship to power and privilege

an advantage that is unearned, exclusive to a particular group or social category, and socially conferred by others

prejudice is an unfavorable preconceived feeling or opinion formed without knowledge or reason that prevents objective consideration of an individual or group.

the unequal treatment of an individual or group based on their statuses (e.g., age, beliefs, ethnicity, sex)

the geographical location where a person was born and grew up

one’s innermost concept of self as male, female, a blend of both or neither – how individuals perceive themselves and what they call themselves. One's gender identity can be the same or different from their sex assigned at birth.

a person who does not conform to norms about sexuality and gender (particularly the ones that say that being straight is the human default and that gender and sexuality are hardwired, binary, and fixed rather than socially constructed, infinite, and fluid).

shared understandings that are jointly accepted by large numbers of people in a society or social group

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture

anyone residing in any given country without legal documentation. It includes people who entered the U.S. without inspection and proper permission from the government, and those who entered with a legal visa that is no longer valid.

a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms

the art, science, or profession of teaching

a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life.

an intense opposition to an internal minority that is seen as a threat to the nation on the grounds of its foreignness

a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are pushed to the outside of society by denying them economic and political power.

an acronym that stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, and more.

the rules or expectations that determine and regulate appropriate behavior within a culture, group, or society

the irrational fear of or prejudice against individuals who are or are perceived to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual people.

a system of oppression designed to reproduce and reinforce the dominance of heterosexual, cisgender men and oppress women and LBBTQIA+ people.