11.3 Harmful Drug Use: Exploring Unequal Outcomes

Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman

Now that we have clarified how our understandings of drug use and harmful drug use are socially constructed, we can explore how differences in social location can influence when drug use is considered problematic and how outcomes may differ. For this section, we will specifically consider geographic location and race and ethnicity to look at the inequality in outcomes.

The War On Drugs – Criminalizing Drug Use

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HSozqaVcOU8

The War on Drugs is an effort in the United States since the 1970s to combat illegal drug use by greatly increasing penalties, enforcement, and incarceration for drug offenders (Britannica 2023b). The War on Drugs was partially in response to a significant global economic recession in the early 1980s. Angela Davis, who we met in Chapter 1, describes it this way:

By 1994, the deindustrialization of the US economy produced by global economic shifts, was having a deleterious impact on working-class Black communities. The massive loss of jobs in the manufacturing sector, especially in cities like Detroit, Philadelphia, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, had the result, according to Joe Willam Trotter, that “the black urban working class nearly disappeared by the early 1990s.” Combined with the disestablishment of welfare state benefits, these economic shifts caused vast numbers of black people to seek other—sometimes “illegal”—means of survival. It is not accidental that the full force of the crack epidemic was felt during the early 1980s and 1990s (Davis 2021).

The massive expenditures on the curtailment of the drug epidemic also shifted our views on drug use. The United States became much more punitive towards drugs. The courts treated harmful drug use as a criminal justice issue rather than as a substance dependence issue. The War on Drugs created tougher sanctions on drug use in America. The Drug Enforcement Agency was created in 1973 to provide another arm of the government to tackle the specific issue of drugs. By the 1980s, lengthy sentences for drug possession were also in place. One to five-year sentences for possession were increased to more than 25 years.

The War on Drugs and its associated policies also drove massive increases in prison populations. Between 1980 and 2010, the US prison population quintupled. The population only began to decline slightly in the early 2010s. As of 2019, the United States still imprisoned more than 2 million people in prisons and jails. Mass incarceration refers to the overwhelming size and scale of the US prison population. The United States has the largest prison population in the world, but how did this come to be the case?

The War on Drugs is one of the major drivers of the prison population in the United States. In 1971, President Richard Nixon declared a War on Drugs, dedicating increased federal funding and resources to quelling the supply of drugs in the United States. This war continued to ramp up through the 1980s and 1990s, especially as crack cocaine became a growing concern in the media and public sphere. Crack cocaine was publicly portrayed as a highly addictive drug sweeping its way through America, allowing politicians to capitalize on this hysteria and pass policies that rapidly increased the prison population. Even so, the vast majority of arrests and enforcement were not of high-level, violent dealers. More often, police arrested small-time dealers or people struggling with addiction. In fact, during the 1990s, the period of the largest increase in the US prison population, the vast majority of prison growth came from cannabis arrests (King and Mauer 2006).

The 1980s and 1990s were also an era where states turned to partnerships with private companies to meet the booming demand for facilities, leading to the rise of private prisons. Private prisons are for-profit incarceration facilities run by private companies that contract with local, state, and federal governments. The business model of private prisons incentivizes them to keep their prisons as full as possible while spending as little as possible on care for inmates. Down 16 percent from its peak in 2012, private prisons still held 8 percent of all people incarcerated at the state and federal level as of 2019 (The Sentencing Project 2022). This general statistic hides state-to-state differences, though. For instance, Oregon has no private prison facilities in the state, while Texas has the highest number of people incarcerated in private prisons.

From the inception of the War on Drugs, racial biases were at the center of these policy changes. For instance, one of Richard Nixon’s top advisors, John Erlichman, explicitly admitted to this in a 2016 interview:

You want to know what this [war on drugs] was really all about? The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and Black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did. (Baum 2016)

The War on Drugs was a deliberately racist set of policies.

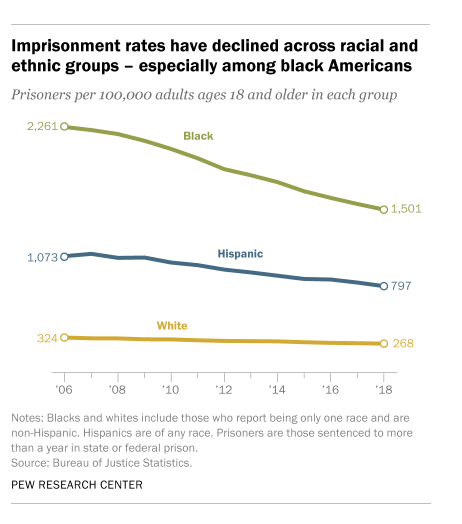

Even as the racial gap in incarceration has narrowed in recent years, the US disproportionately incarcerates Black Americans. While Black Americans make up 12 percent of the population, they make up over 33 percent of incarcerated individuals (Gramlich 2019). Similar trends exist among Latino Americans: while Latinos comprise 16 percent of the US population, they account for 23 percent of incarcerated individuals (Gramlich 2019). In contrast, while White Americans comprise 63 percent of the population, they only make up 30 percent of those incarcerated (Gramlich 2019).

This network of policies and unequal institutional practices led to what scholar Michelle Alexander terms The New Jim Crow. The New Jim Crow refers to the network of laws and practices that disproportionately funnel Black Americans into the criminal justice system, stripping them of their constitutional rights as a punishment for their offenses in the same way that Jim Crow laws did in previous eras. Because of these new mass incarceration policies, a new iteration of the racial caste system has emerged: one where Black Americans can legally be denied public benefits, housing, the right to vote, and participation on juries because of a criminal conviction.

The War on Drugs was a racialized response to a worldwide economic downturn. We had other options. James Forman Jr. puts it this way:

Rising levels of abuse, addiction, and drug-related violence should have been a sign that something was wrong with America. It should have led the nation to focus on the myriad ways in which 350 years of white supremacy had produced persistent Black suffering and disadvantage. It should have caused politicians to interrogate the cumulative impact of convict leasing, lynching, redlining, school segregation, and drinking water poisoned with lead. Instead of asking, “What kind of people are they that would use and sell drugs?” The nation should have been asking a question that, to this day, demands an answer: ”What kind of people are we that build prisons while closing treatment centers (Forman 2021 354).

Our response to drug use, not the drug use itself, is the social problem. Social justice requires a different response.

Unpacking Oppression, Quantifying Justice

- “Approximately two-thirds of all federal prisoners are in prison for violent crimes or had a prior criminal record before being incarcerated” Christopher A. Wray, Assistant Attorney General, 2004, as quoted by The Sentencing Project 2004.

- Nearly three-quarters of the people in federal prison are nonviolent offenders with no history of violence.

- Black men are disproportionately arrested and imprisoned.

These statements are all true, but what do they actually mean? Sociologists look at patterns of difference or change over time to measure inequality between groups and to explain it. Social problems sociologists often explore the efficacy of possible interventions. Because we want to take effective action, we must examine the information we use to make decisions very carefully.

We see deep inequalities in our criminal justice system. However, we also see competing claims about what is true. How, for example, can the first two statements be true at the same time? The issue lies in combining two populations in the first statement—people who commit violent crimes and people who have a prior criminal record. Getting a prior criminal record might include being arrested for being at a protest, even if you weren’t convicted. It could include failure to pay child support. It could also include having a few grams of cannabis in Oregon prior to 2015 when the related law changed. Many people have a criminal record, but they are not actually dangerous to society.

When you examine the second statement, it only includes one group of people: people who are in prison for non-violent offenses. Many of these offenses are related to drug possession, and some of them are related to drug distribution. Although harmful drug use causes harm, these offenses are non-violent. By looking at the numbers in this way, we open the door to considering options for social justice that are effective rather than carceral.

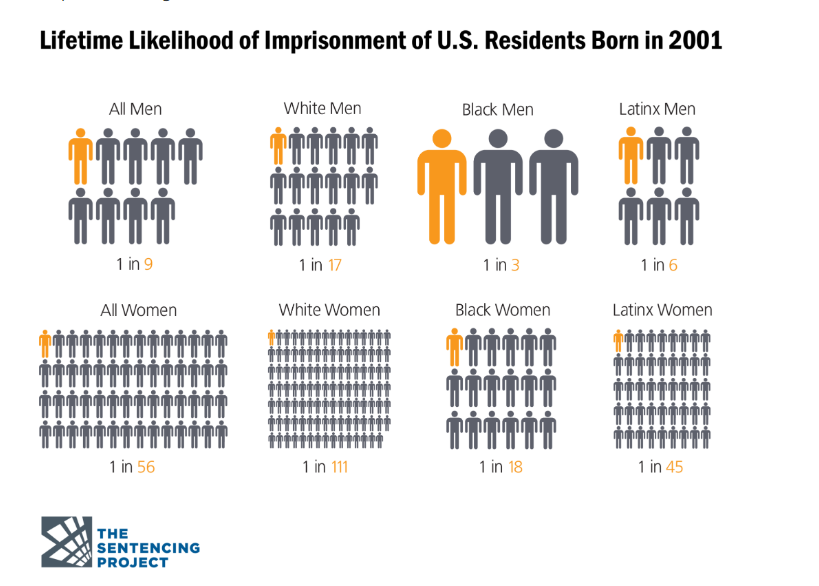

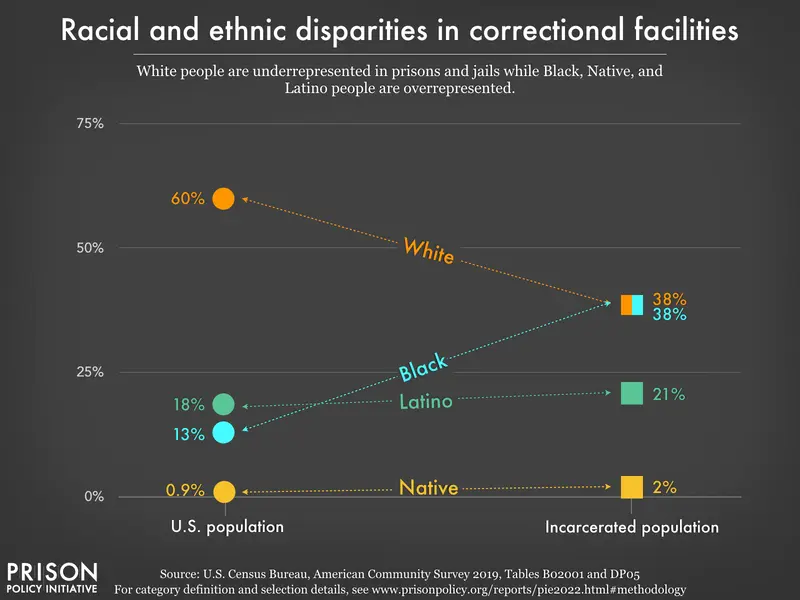

Disproportionality is the overrepresentation or underrepresentation of a racial or ethnic group compared with its percentage in the total population, as we discussed in Chapter 6. We can see disproportionality across groups of many social locations. Racial disproportionality is commonly related to harmful drug use and the criminal justice system. As we see in Figure 11.8, White people make up 60% of the overall population of the United States, but they make up only 38% of people who are incarcerated. Black people make up 13% of the overall population of the United States, but they are also 38% of the incarcerated population. Hispanic people are 18% of the total population and 21% of people in prison or jail. Finally, Native Americans are .9% of the population and 2% of those in jail. In every case, we see disproportionality.

However, the measure of disproportionality doesn’t tell us why the difference exists or what to do about it. If you consider the infographic The Social Ecological Framework of the Opioid Crisis (Figure 11.2), you see many causes of inequality.

The causes of disproportionality are often disparity. Disparity is the unequal outcomes of one racial or ethnic group compared with outcomes for another racial or ethnic group (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2021). Disparity can be used to compare any groups with different social locations.

However, as we consider the War on Drugs as an example, we see that systems, laws, policies, and practices privilege White people over People of Color. In one example, the sentencing for crack cocaine and powder cocaine (Figure 11.9) are significantly different. Distributing 5 grams of crack cocaine has a 5-year mandatory minimum federal prison sentence. Distributing 500 grams of powder cocaine has the same sentence. More than 80% of the crack cocaine defendants in 2002 were Black, even though two-thirds of the crack cocaine users were White or Hispanic (The Sentencing Project 2004). Powder cocaine is more likely to be used by wealthier people, who are disproportionately White (Vagins and McCurdy 2006).

Even when judges have more discretion in what sentences they impose, racial disparities exist:

Racialized assumptions by key justice system decision makers unfairly influence outcomes for people who encounter the system. In research on presentence reports, for example, scholars have found that People of Color are frequently given harsher sanctions because they are perceived as imposing a greater threat to public safety and are therefore deserving of greater social control and punishment. (Nellis 2021:12-13)

These biases are both conscious and unconscious, and they occur at every level of the criminal justice system, from police to lawyers, to judges, to the politicians who make the laws in the first place. Structural racism and individual racist ideas result in racial disparity in the criminal justice system.

It’s your turn to unpack oppression and quantify justice:

- Examine the racial and ethnic composition of the criminal justice system in your state. You can use The Color of Justice or State Prison Growth in 50 States, but you are free to find additional sources.

- What cause of this disproportionality is relevant to people in your state? For example, Oregon doesn’t have private prisons, so that couldn’t be a factor in imprisonment disparities here.

- What changes in the criminal justice system might lower the total number of people involved in the system or decrease racial and ethnic disparities? You might look at Winnable Criminal Justice Reforms in 2023 for some ideas.

The Opioid Crisis: Medical Intervention, not Crime

Another way to notice racism at work in response to harmful drug use is to examine the opioid crisis. The opioid crisis refers to the surge in fatal overdoses linked to opioid use (DeWeerdt 2019). The overdose fatality rate rose by 345% between 2001 and 2016 (Jalali et al. 2020). Opioids are a class of drugs that cause euphoria. Opioids include heroin, morphine, codeine, hydrocodone, OxyContin®, and fentanyl (Johns Hopkins Medicine 2023). Heroin is an illegal drug. The others are prescription drugs that doctors prescribe for pain relief.

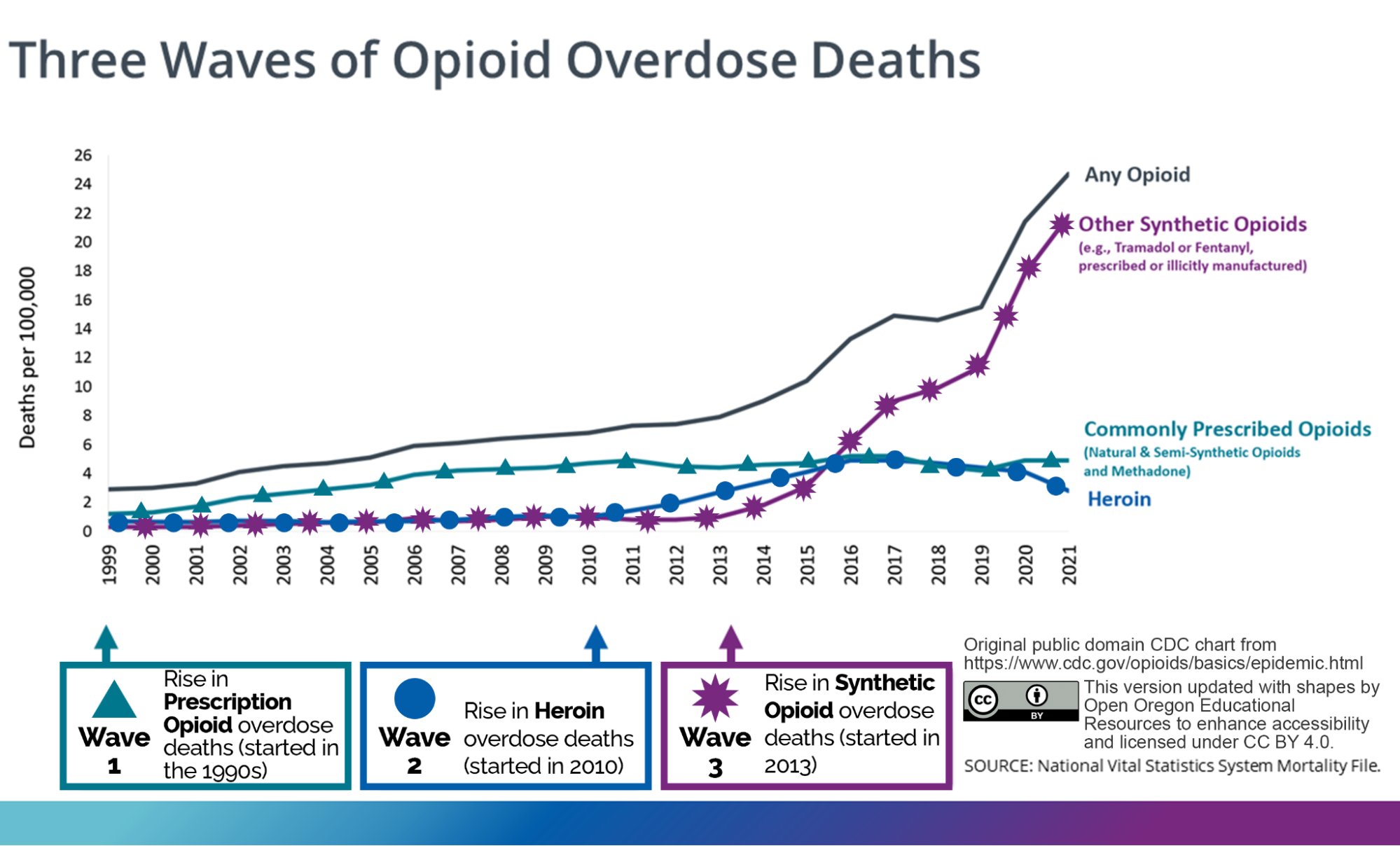

Nearly 75% of drug overdoses in 2020 involved a legal or illegal opioid (Centers for Disease Control 2022). The CDC describes the crisis using three waves. The first wave started in the 1990s. In this wave, the deaths were primarily due to overdoses on prescription opioids, like OxyContin® and Vicodin®. This wave was a result of the overprescription of opioid-based painkillers, causing some individuals to become physically dependent.

The second wave started in 2010. The second wave was due to overdoses related to using heroin. This use of heroin partially resulted from a decrease in the amount of legally available prescription painkillers.

The third wave started in 2013. This wave marked an increase in overdose deaths from synthetic opioids like fentanyl and tramadol. While fentanyl can be prescribed, this wave was driven by illegally manufactured substances.

The response to heroin use and misuse was carceral. It was part of the war on drugs that we described in the previous section.

Race was at the core of drug policy that emerged from an increase in heroin use in urban centers in the 1960s. According to media accounts, the face of the heroin user at that time was “black, destitute and engaged in repetitive petty crimes to feed his or her habit” (Hart and Hart 2019:7). A popular solution to this racialized drug scare was to incarcerate Black users of heroin and offer methadone treatment to White users.

New York state was a forerunner in creating harsh drug laws to address heroin use in cities. The infamous Rockefeller drug laws of 1973 created mandatory minimum prison sentences of 15 years to life for possession of small amounts of heroin and other drugs (Hart and Hart 2019). 90 percent of those convicted under the Rockefeller drug laws were Black and Latinx, though they represent a smaller proportion of people who use drugs in the population (Drucker 2002).

The societal response to opioid use and dependence among White people during this crisis has been gentler, relying more on treatment than the criminal justice system (Hart and Hart 2019; James & Jordan 2018). According to statistics from the Bureau of Justice, 80 percent of arrests for heroin trafficking are among Black and Latinx people, even though White people use heroin at higher rates and are known to purchase drugs within their own racial community (James & Jordan 2018).

As we examine the response to the overprescription of opioids and the harmful use of fentanyl, we see a stark difference in public response. We see a focus on monitoring doctors so that they don’t overprescribe opioids. We see a focus on the overuse of opioids as a medical disease needing treatment rather than criminalizing the user of the drug. Our response to drug overuse in the opioid crisis is racialized. Researchers Netherland and Hansen summarize the unequal response this way:

The public response to White opioids looked markedly different from the response to illicit drug use in inner city Black and Brown neighborhoods, with policy differentials analogous to the gap between legal penalties for crack as opposed to powder cocaine. This less examined ‘White drug war’ has carved out a less punitive, clinical realm for Whites where their drug use is decriminalized, treated primarily as a biomedical disease, and where White social privilege is preserved… in the case of opioids, addiction treatment itself is being selectively pharmaceuticalized in ways that preserve a protected space for White opioid users, while leaving intact a punitive, carceral system as the appropriate response for Black and Brown drug use. (Netherland and Hansen 2017)

We can see a racialized response in the differential access to treatment options for the harmful use of opioids White people who use opioids have been given more access to the preferred addiction treatment medication, buprenorphine. Treatment with buprenorphine is less stigmatized because it is dispensed like any other pharmaceutical medication at a private doctor’s office

Another treatment option is methadone. This method requires frequent visits to a methadone clinic. Often BIPOC receive treatment at the less-preferred methadone clinics (Hansen 2015). Politicians legalized Buprenorphine treatments for opioid use disorder, supporting the privileged lives of middle-class White addicts (Netherland & Hansen, 2017).

These characteristics of the social landscape contribute to increased health harms, such as contracting HIV or hepatitis C, for Black people who use drugs. Health harms caused by substance use are higher among Black people who use drugs, not because they participate in riskier drug use behavior, but because they reside in under-resourced communities that hinder access to health-promoting services and materials (Cooper et al. 2011). Accordingly, opioid overdose rates for Black people have historically been higher than those for White people in some states. Recently this rate has been increasing more rapidly, though the media attention surrounding the opioid crisis mostly focuses on drug use by White people (James & Jordan 2018).

We also see differences in the harm caused by harmful drug use because of the lack of treatment centers in rural areas. The lack of treatment centers harms White people who live in these areas and People of Color.

Anthropologist Angela Garcia, shown in Figure 11.11, spent several years researching heroin use among members of a Latinx community in rural New Mexico. Her findings point to the loss of a connection to land and livelihood and the experience of settler colonialism as social determinants of harmful heroin use (2010). Settler colonialism, as we explored in Chapter 8, is a system of power that normalizes the continuous settler occupation of Indigenous lands and exploitation of Indigenous resources. It is Eurocentric in nature and assumes that European White ideas and values are superior (Cox 2017).

Garcia’s research found that dispossession of ancestral lands ruptured the link to cultural heritage and caused impoverishment. Together the disconnection and poverty formed a source of never-ending emotional pain for users of heroin. The sparsely populated rural setting also meant that drug treatment was less available. By examining the history of dispossession and oppression that impacted this community, Garcia shows how the social determinants of harmful drug use can illuminate the root social causes of the problem. If you would like to learn more, please watch Angela Garcia on “Postcolonial theory and psychological anthropology” [Vimeo Video]. In it, Garcia discusses her relationship with the families that she studied.

Licenses and Attributions for A Harmful Drug Use: Exploring Unequal Outcomes

Open Content, Original

“Harmful Drug Use: Exploring Unequal Outcomes” by Kelly Szott and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 11.10. “Three Waves of the Opioid Overdose Deaths” updated by Open Oregon Educational Resources for accessibility is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Based on “Three Waves of Opioid Overdose Deaths” by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is in the Public Domain.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“War on Drugs” definition from “Current Issues and Crime Problems in Corrections” by Sam Arungwa, Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System: An Equity Lens [manuscript in press], which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications: lightly edited.

“Mass Incarceration” and “The New Jim Crow” definitions from “Race, Identity, and the Criminal Justice System” by Alexandra Olsen, Matt Gougherty, and Jennifer Puentes, Sociology in Everyday Life [manuscript in press], which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“The War On Drugs – Criminalizing Drug Use” is adapted from “Race, Identity, and the Criminal Justice System” by Alexandra Olsen, Matt Gougherty, and Jennifer Puentes, Sociology in Everyday Life [manuscript in press], which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: lightly edited.

Figure 11.9. “Photo” by Colin Davis is licensed under the Unsplash License.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 11.4. “What is the Drug War? With Jay-Z & Molly Crabapple” by Drug Policy Alliance is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 11.5. “Lifetime Likelihood of Imprisonment of US Residents Born in 2001” © The Sentencing Project is included under fair use.

Figure 11.6. “Photo” from “Racial Justice Requires Ending the War on Drugs, Experts Say” by Emaline Friedman, Mad in America is in the Public Domain.

Figure 11.7. “Imprisonment rates have declined across racial and ethnic groups – especially among black Americans” from “Black Imprisonment Rate in the US Has Fallen by a Third since 2006” by John Gramlich © Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. is licensed under the Center’s Terms of Use.

Figure 11.8. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Correctional Facilities” from “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2023” by Wendy Sawyer and Peter Wagner © Prison Policy Initiative is included under fair use.

Figure 11.11. “Photo of Dr. Angela Garcia” © Stanford University is all rights reserved and included with permission.

a socially constructed category with political, social, and cultural consequences, based on incorrect distinctions of physical difference

a group of people who share a cultural background, including language, location, or religion.

an effort in the United States since the 1970s to combat illegal drug use by greatly increasing penalties, enforcement, and incarceration for drug offenders.

a civil force in charge of regulating laws and public order at a federal, state, or community level

a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite adverse consequences.

for-profit incarceration facilities run by private companies that contract with local, state, and federal governments.

the network of laws and practices that disproportionately funnel Black Americans into the criminal justice system, stripping them of their constitutional rights as a punishment for their offenses in the same way that Jim Crow laws did in previous eras

a system that relies on legal codes, criminalization, policing, and punishment to mediate conflict, protect property, and maintain social order.

the overwhelming size and scale of the U.S. prison population.

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world

a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture

full and equal participation of of all groups in a society that is mutually shaped to meet their needs

of, relating to, or suggesting a jail or prison

the unequal outcomes of one group compared with outcomes for another group. Disparity can be used to compare any groups with different social locations.

the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care and criminal justice

the unequal outcomes of one racial or ethnic group compared with outcomes for another racial or ethnic group.

a surge of drug overdoses and suicides, both linked to the use of opioid drugs

an acronym that stands for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. It is used to refer to people whose communities have been historically under-resourced, over-policed, disproportionately impacted by social problems, and underrepresented in terms of institutional power in the United States because of their assigned race category.

a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

areas with relatively high poverty rates that lack robust economic infrastructure. While the term often refers to cities and suburbs with populations of over 250,000 people, many rural communities are also under-resourced (adapted from Eberhardt, Wial, and Yee 2020:5).

areas are sparsely populated, have low housing density, and are far from urban centers.

the state of lacking the material and social resources an individual requires to live a healthy life.