6.2 Housing Insecurity and Houselessness as a Social Problem

Nora Karena

As you recall from Chapter 1, social problems go beyond the experience of the individual, resulting in a conflict in values, arising when groups of people experience inequality, is socially constructed by real consequences, and must be addressed interdependently. A basic inequality, of course, is that some people have secure housing, and some don’t. Social locations such as gender identity, race, class, age, sexual orientation, or combinations of these factors can increase the risk of becoming unhoused.

Defining Houselessness

Harris, a student in the Oregon Coast Community College Social Problems class, explored how houselessness can be seen as a social problem. She interviewed Traci Goff, the executive director of Grace Wins Haven, a day shelter in Newport, Oregon, about houselessness in Lincoln County.

Harris found that houselessness goes beyond the experience of an individual. They document this in the graphic novel hosted in figure 6.3. The City of Newport, Oregon, passed a new ordinance in 2022 which regulates who can camp. The new law prohibits people from camping near city buildings, schools, or in recreational areas. These restrictions apply to the entire community, not just individual people.

Harris also identifies the many organizations and people who have differing opinions about houselessness in Lincoln County. The city government, the State of Oregon, Grace Wins Haven, and the houseless people themselves disagree on what should be done.

Many of the people that Harris talks to also experience marginalization based on their social location. One young person is autistic. Another person experiences chronic and severe physical illness. Another client was a felon, which restricted his ability to rent many properties.

Finally, our ideas about who is houseless and why they are houseless are socially constructed. In their creative approach, Harris notes that many laws, policies, and economic forces create houselessness, not just the behavior of individuals. We’ll look deeper at how explanations of why people are houseless have changed over time later in this chapter. Let’s start, though, with some formal definitions.

Homelessness is defined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) as being unsheltered, having inadequate shelter, not having a permanent fixed residence, and/or lacking the resources to secure stable housing (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2012). HUD uses four categories of homelessness, as described in figure 6.4, to determine eligibility for housing services. These subsidized and supported housing services include Emergency Shelters, Transitional Housing, Rapid Rehousing, Housing Choice Subsidized Housing Vouchers (also known as Section 8), and Homelessness Prevention Services.

| U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Category of Homelessness | Definition | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Literally Homeless | Individual or family who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, meaning:

|

An individual or family only needs to meet one of the three subcategories to qualify. |

| 2: Imminent Risk of Homelessness | An individual or family who will imminently lose their primary nighttime residence, provided that:

|

Includes individuals and families who are within 14 days of losing their housing, including housing they own, rent, are sharing with others, or are living in without paying rent. |

| 3: Homeless Under Other Federal Statutes | Unaccompanied youth under 25 years of age or families with Category three children and youth who do not otherwise qualify as homeless under this definition but who:

|

Includes individuals and families who are within 14 days of losing their housing, including housing they own, rent, are sharing with others, or are living in without paying rent. |

| 4: Fleeing/Attempting to Flee Domestic Violence | Any individual or family who:

|

Domestic Violence includes dating violence, sexual assault, stalking, and other dangerous or life-threatening conditions that relate to violence against the individual or family member that either takes place in or him or her afraid to return to, their primary nighttime residence (including human trafficking). |

Who is Unhoused?

Shelter is a basic human need. Surviving unsheltered takes a toll on physical and mental health, both in terms of increased health risks and decreased access to adequate healthcare services (Kushel et al. 2006). Having safe and stable shelter supports our basic psychological needs, anchors our social relationships, and is necessary for economic stability. In 1992, the United Nations declared that adequate housing is a human right. The value of shelter to the quality of human life is clear. However, rates of houselessness in the United States are growing. What values do you think conflict with the value of meeting everyone’s basic human needs?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcZvD7lKZto

The image in figure 6.5 and the video in figure 6.6 tell part of the story of houselessness in Portland, Oregon. Please take the time to watch the first 6 minutes of this 11 minute video that tells this story. As you watch, consider who is speaking and whose voices are not heard. These stories are powerful but insufficient. Who else in Oregon is houseless?

On the night of January 26th, 2022, when the temperature dipped down into the 20s, at least 14,655 unhoused people were counted in Oregon. In Multnomah, Washington, and Clackamas Counties, 6,633 people were unhoused, an increase of more than 25 percent since the last count in 2019 in Multnomah County alone (Hasenstab 2022). Of those counted, 3,525 met the HUD definition of unsheltered from figure 4.2, while 3,108 spent that cold winter night in temporary shelter or transitional housing. More than 60 percent of the unhoused people that night met the definition of chronically homeless, having a disabling condition, and having been unhoused for at least 12 months (Multnomah County 2022). The annual Point-in-Time count of unhoused people does not consider people who were temporarily doubled-up with friends and family unhoused, even though they also lack a permanent residence.

Encampments of unhoused people, sometimes called tent cities, have become a common, often unwelcome fixture in Portland. You can read about Dignity Village in Portland, Oregon [Website], an encampment community that is self-organized and offers some security. Because many encampments are not officially legal, people living in them lack stability and live under the threat of being “swept” or evicted. In 2017, 255 encampments were reported across the United States, ranging in size from 10 to over 100 people living in them, but that number does not include many more illegal encampments. Encampments are a response to the fact that shelters constantly operate at maximum capacity, and communities do not have enough affordable housing (Tent Cities in America 2022).

Shelters provide needed temporary immediate service to over 1.5 million Americans each year. Many nonprofit organizations also provide additional supportive services and housing assistance for families and individuals. Day shelters, such as Rose Haven in Portland, Oregon, also offer support and food to unhoused people. Some churches allow people to car-camp and/or erect tents on the church property and have provided hygiene centers that include showers, hand-washing, laundry, and food services.

Tensions exist between tent dwellers, staff, and users of shelters, and the business and home-owning communities since being unhoused is messy, and people who are unhoused are vulnerable to crime and abuse. In Corvallis, Oregon, the community has struggled for years to find a permanent location for the men’s overnight cold-weather shelter. Advocates for people who are unhoused argue for a location close to needed city services; accessibility is important when walking, bicycling, and public transportation are the primary modes of getting around.

Who is Housing Insecure?

Housing insecurity is a broad set of challenges, such as the inability to pay rent or utilities or the need to move frequently (Goldrick-Rab et al. 2019). According to government definitions, if a person or a family are within 14 days of losing their housing and does not have the resources “to obtain permanent housing,” they are considered by HUD to be “at imminent risk of homelessness.” Housing instability can be harder to see than houselessness. Signs of housing instability include missing a rent or utility payment, having a place to live but not having certainty about meeting basic needs, experiencing formal or informal evictions, foreclosures, couch surfing, and frequent moves. It can also include exposure to health and safety risks such as mold, vermin, lead, overcrowding, and personal safety fears such as abuse.

Of all Americans, 10 to 15 percent are housing insecure. A cost burdened household is a household in which 30 percent or more of a household’s monthly gross income is dedicated to housing, making it difficult to pay for necessities. Households that pay more than 30 percent of their income on housing face housing instability and insecurity. One study used a residual-income approach, which estimates whether households have enough money left after paying rent and utilities to afford a decent standard of living, and found that 19.2 million (62.1 percent) were cost burdened. However we measure it, the cost burden puts people at risk for being homeless (National Low Income Housing Coalition 2022).

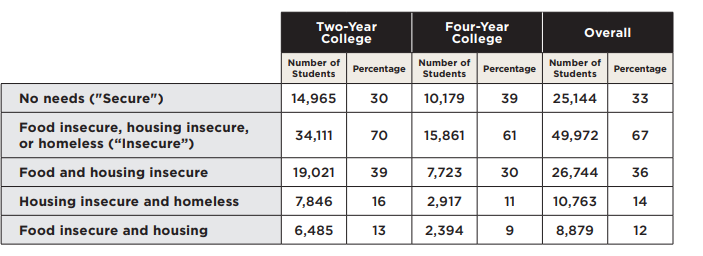

College students are another group of people who are often housing insecure. You watched a video of their stories earlier in this chapter. In addition to qualitative stories, we have quantitative data about how many college students experience housing instability (figure 6.7).

A recent national survey that included Linn-Benton Community College (LBCC) in Albany, Oregon, found that students at the two-year institution had higher levels of houselessness than their counterparts nationally. You can see the results from all surveyed colleges in figure 6.7. With a response rate of 9.7 percent, 558 of 5,700 surveyed LBCC students participated in the 2019 #RealCollege Survey Report. Nineteen percent of LBCC students reported experiencing houselessness in the past year, compared with 17 percent nationally. In addition, 53 percent of LBCC students reported experiencing housing insecurity in the past year, compared with 50 percent nationally (Goldrick-Rab et al. 2019). This report indicates that more than half of community college students are struggling with stress related to having a safe, stable place to care for themselves and their families.

The College and University Basic Needs Insecurity Report found that being female, transgender, Native American, Black, Latinx, and 21 or older increased your chances of being housing insecure or homeless. Although men, people who are White, young White students (18–20), and athletes were less likely to experience houselessness or housing insecurity, they still did so in double-digit percentages (Goldrick-Rab et al. 2019).

In Oregon, in particular, the median individual and household income in 2020 was $35,393 and $65,677, respectively. Average rents also increased significantly (U.S. Census 2020). More than 35 percent of Portland renters surveyed reported being behind on rent, and more than 56,000 households in the Portland region are considered housing insecure (Bates 2020).

Rural communities have unique housing pressures, especially in resort areas where housing stock tends to be inadequate. One rural area is Lincoln County, Oregon, where wages are generally lower than most of the rest of the state. The average income of a Lincoln County resident is $25,130 a year (BestPlaces 2020). If we calculated that a person could only use 30 percent of their income for housing to remain stable, their rent could be $7,539 per year or $628.25 per month.

The fair market rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Lincoln County is $877 (RentData.org 2022). At fair market value, the renter would be paying about 42 percent of their income. When you add that less than one percent of all homes in Lincoln City, Oregon, are vacant and available to rent (Bestplaces 2020), you begin to see the fragility of our housing system. Even when work is plentiful, houselessness is only a step away. One job loss, one major illness, or commonly, one landlord who chooses to sell their property rather than continue to rent, and houselessness occurs.

Licenses and Attributions Housing Insecurity and Houselessness as a Social Problem

Open Content, Original

“Housing Insecurity and Houselessness as a Social Problem” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.4. “Categories of Homelessness” adapted from The Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“LBCC Student Statistics and likelihood of student homelessness,” “Homeless encampments, Dignity Village, and tent cities,” and “Housing insecure” are partially adapted from “Finding a Home: Inequities” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Carla Medel, Katherine Hemlock, and Shonna Dempsey, Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 2e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Nora Karena are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.5. “Northeast Portland homeless camp tents” by Graywalls is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 6.3. “Houselessness: Grace Wins Haven” by Harris is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 6.6. “City of Roses or City of Homeless? Portland’s human tragedy” by KOIN 6 is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 6.7. “Food Insecurity and Housing Insecurity at Two-year and Four-year Colleges” by the Hope Center is included under fair use.

Figure 6.8. “Homeless service providers say counting homeless in rural areas can be more difficult because they are often less visible than in urban areas” by Molly Solomon, OPB is included under fair use.

one’s innermost concept of self as male, female, a blend of both or neither – how individuals perceive themselves and what they call themselves. One's gender identity can be the same or different from their sex assigned at birth

a socially constructed category with political, social, and cultural consequences, based on incorrect distinctions of physical difference

a group who shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation

a person’s emotional, romantic, erotic, and spiritual attractions toward another person

lacking a place to live

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world

a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are pushed to the outside of society by denying them economic and political power

the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location that define an individual or group in relationship to power and privilege

being unsheltered, having inadequate shelter, not having a permanent fixed residence, and/or lacking the resources to secure stable housing

a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life

a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity

an ideal or principle that determines what is correct, desirable, or morally proper

a broad set of challenges, such as the inability to pay rent or utilities or the need to move frequently

the money a person earns from work or investments

A large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society

areas are sparsely populated, have low housing density, and are far from urban centers