7.2 The Social Problem of Belonging: Who is Family?

Kimberly Puttman

All of us want to belong. Social scientists say that everyone needs to feel connected in some way. Throughout this book, we notice how much we are already interconnected. Why are we talking about the social problem of belonging and not the social problem of family?

First, we talk about belonging because lack of belonging is a cause and consequence of many social problems. Belonging is a feeling of deep connection with social groups, physical places, and individual and collective experiences. It is a fundamental human need that predicts numerous mental, physical, social, economic, and behavioral outcomes (Allen et al. 2021). One of the smallest social groups we might belong to is a family. Families also belong in communities and wider society.

Also, even though this chapter is about family, the social problem we are examining isn’t the family itself. It’s that some families belong and some don’t. We can explore this using the five characteristics of a social problem, that we defined in Chapter 1.

A social problem goes beyond the experience of an individual

At first glance, it may be obvious that a family is about more than one person, so the social problem of family would easily meet this criterion. However, let’s look a little deeper.

You may be making decisions in your family right now—whether to homeschool your child or go back to work, how to take care of your aging parent, and whether you want to have kids. Each choice is yours to make. However, the values and inequalities of our society influence the choices we have.

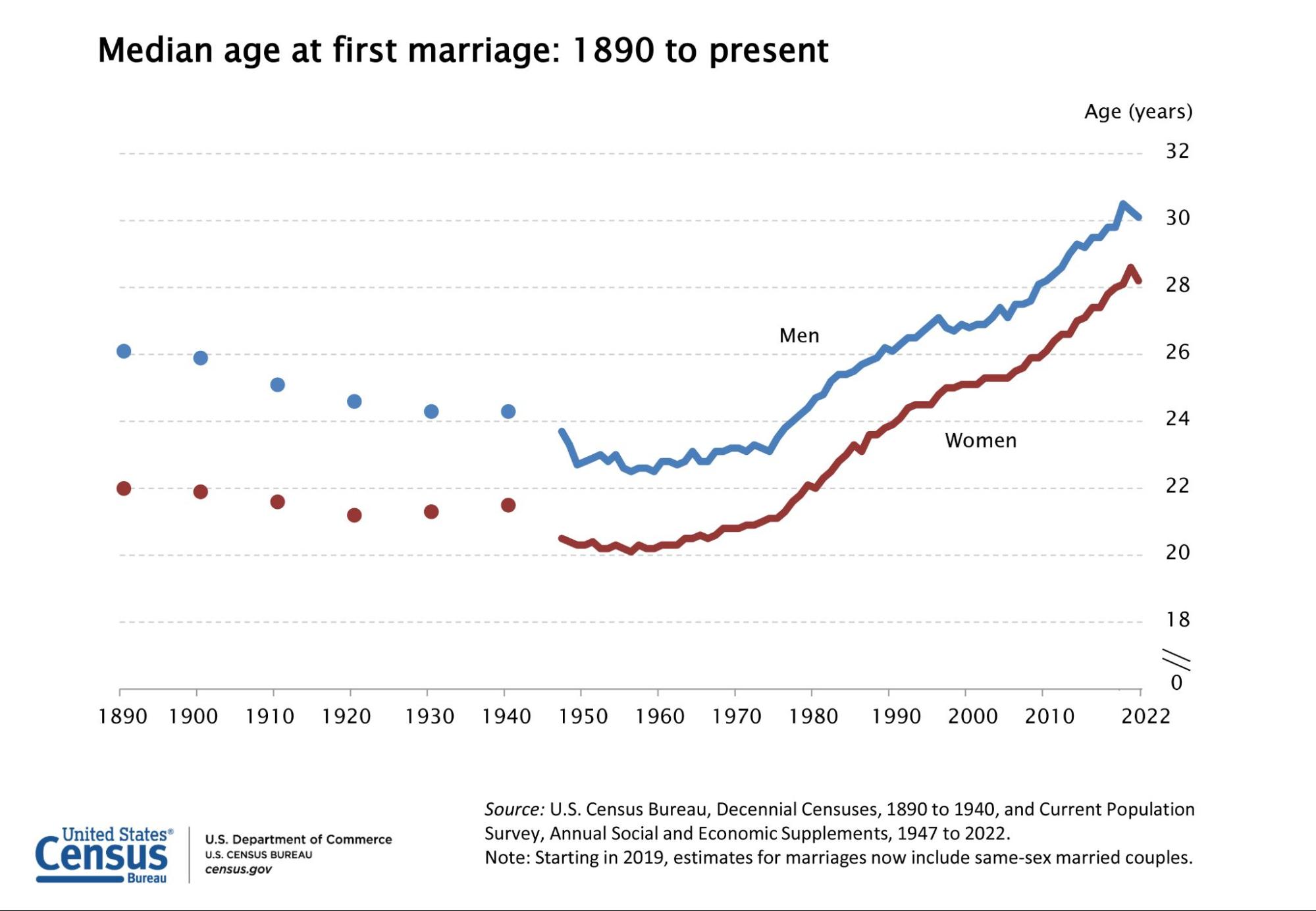

For example, sociologists examine when people get married. These norms change over time. The median age of first marriage for both women (red, bottom line) and men (top, blue line) has increased by nearly ten years since the 1960s.

For example, we can look at the age at which it is normal or expected to get married in figure 7.2. In the United States, the average age of first marriage for women is 26.5 years as of 2010. And only 51 percent of all adults in the United States are married (Cohn et al. 2011). When and whether you get married is a wider social pattern that sociologists can measure and explain. Some causes include increased education, decreased stigma around being unmarried, and higher costs of living.

But what about who you marry? That’s an individual choice, right?

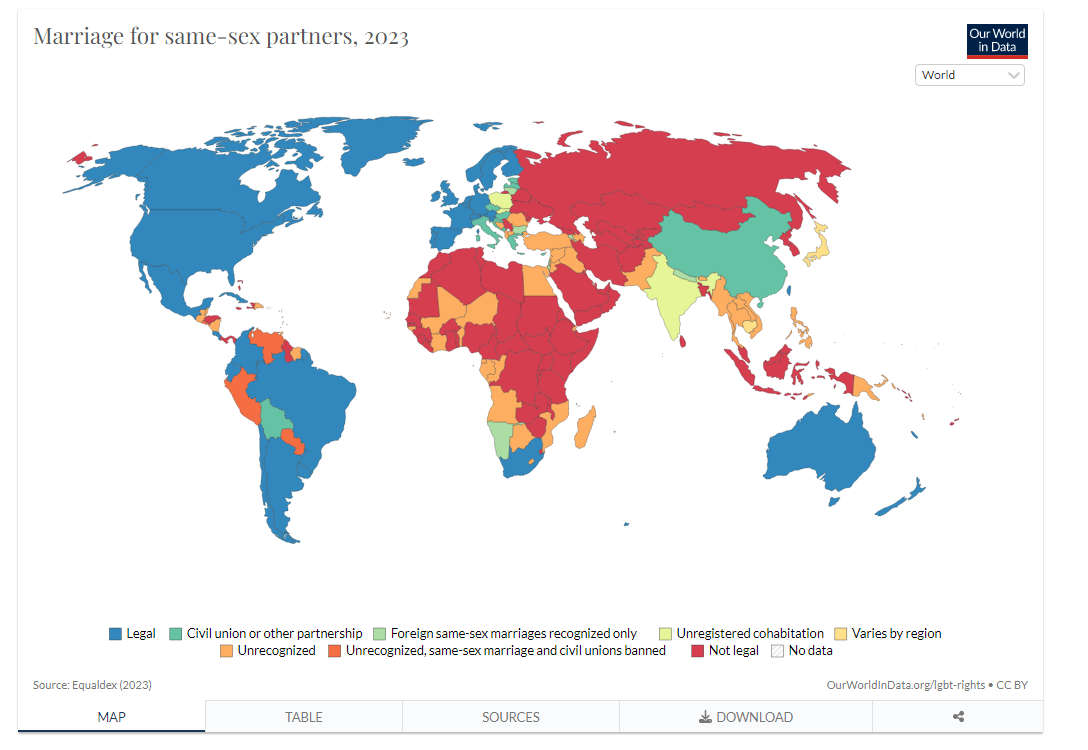

Actually, governments regulate who you can marry. On a worldwide scale, some countries allow marriage for same-sex couples, and some don’t. You can see this information for yourselves in figure 7.3.

These are just two examples of how creating a family goes beyond the experience of the individual. Family is influenced by wider laws, policies, and practices. This begins a social problem.

A social problem results from a conflict in values

A second characteristic of a social problem is that it results from a conflict in values.

One of the biggest conflicts in values relates to who is considered family. Let’s look at two common family forms.

The traditional American family has been identified as the nuclear family, a family group that consists of two parents and their children living together in one household. This family is most often represented as a male and female heterosexual married couple who is middle class, White, and with several children. When society or the individuals within a society designate one kind of family to be traditional, they value this kind of family structure with these particular social characteristics. This is sometimes called the “Leave It to Beaver family” after the popular sitcom television show that ran from 1957 until 1963 (figure 7.4).

The nuclear family form is common in individualist societies. An individualistic society emphasizes the needs and success of the individual over the needs of the whole community. People attribute success to the hard work of the individual person (Cherry 2023). People more often pick their partners based on romantic love or at least individual choice (Bejanyan et al. 2014). Laws, policies and practices in the United States often assume that the nuclear family is the best family form.

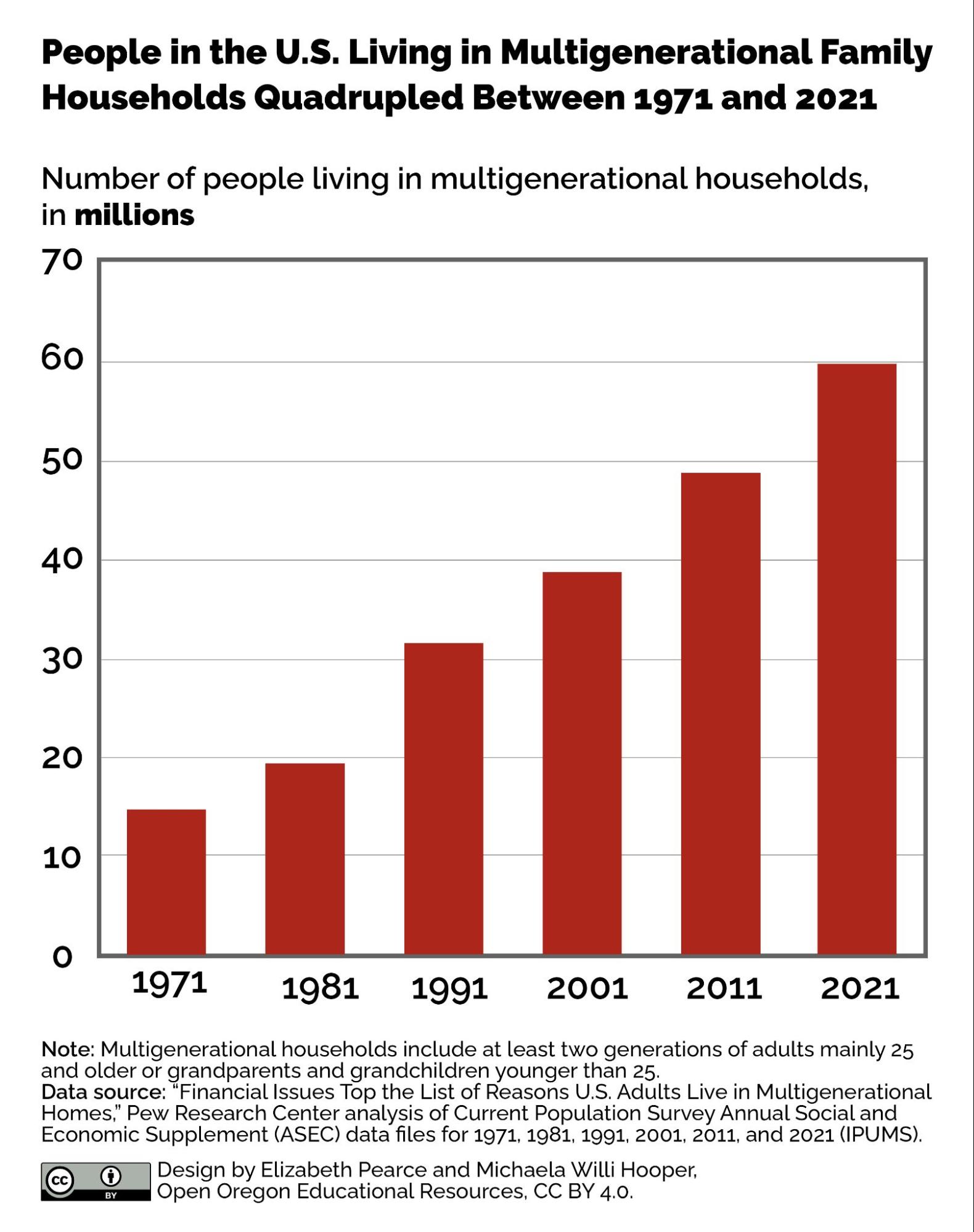

However, this is not the only way to create a family. In the United States, the number of people living in multigenerational households is increasing. Multigenerational families include those families with two or more adult generations and families with grandchildren under age 25 and grandparents living together.

People living in multigenerational households say they save money by living together. Some people say that caring for an elderly adult or young children is a reason to live together (Mitchell 2022). Currently, in the United States, Asian, Hispanic, and Black families are more likely to live in multigenerational households than White families. (Mitchell 2022) However, this family form was also common for White families before the 1950s. (Shayesteh 2023). Before the 1950s and the rise of suburban architecture, the extended or multigenerational household was the most common family form.

Extended families are common in collectivist societies. A collectivist society focuses on meeting the needs and goals of all members of a group rather than focusing on individual successes. Interconnected relationships with families and communities are important, and form a key part of an individual’s identity (Cherry 2022). In collectivist societies, your family might help you pick your partner, in part based on whether they got along with your relatives (Bejanyan, Marshall, and Ferenczi 2015).

As we think about the social problem of belonging, we can see that our changing family forms reveal deep conflicts in values around family.

A social problem arises when groups of people experience inequality

In Chapter 5 we talked about inequality in education. Some families lived in school districts that had limited funds to spend on education. Other families lived in school districts that could afford to have their school lunches catered by local restaurants.

In Chapter 6 we looked at who had a home. We discovered that although single men made up the greatest share of houselessness, women-headed households were more likely to be poor, and more likely to be houseless. We also noticed that because of generational inequality, Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous people experience less housing stability than White people.

These are all measures of inequality. Not all families have the same access to the resources they need to care for themselves. We’ll examine inequality more deeply in the chapter section Inequality in Belonging.

A social problem is socially constructed but real in its consequences

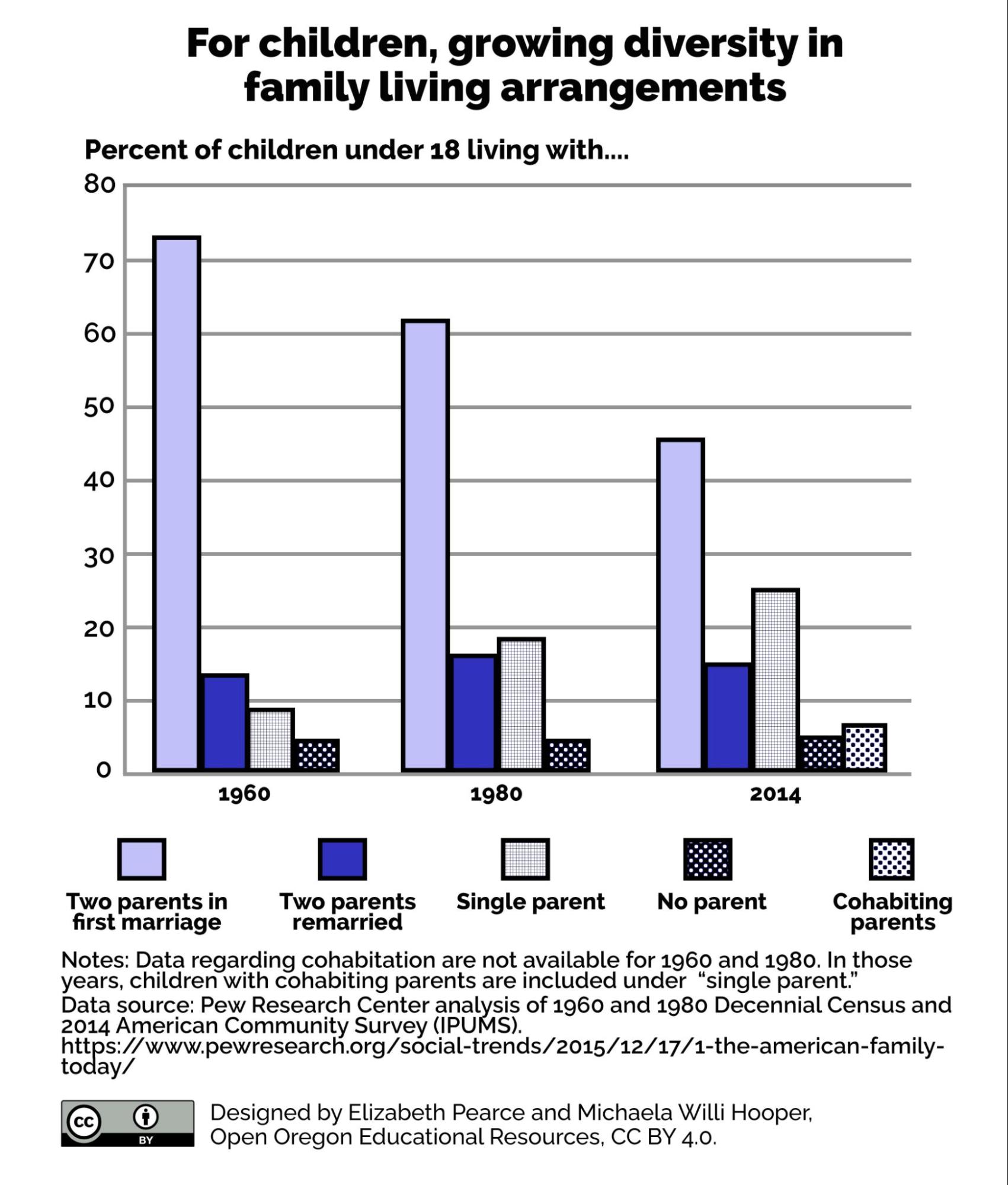

When sociologists examine the ways in which people live together, they notice that diversity in family forms is increasing. When you examine the graph in figure 7.6, you might notice that two parents in their first marriage comprised over 70 percent of all families in 1960. In 2014, on the other hand, approximately 45 percent of these families were two-parent first marriages. We see the growth of single-parent families and parents who cohabitate. We also see an increase in blended families, consisting of two or more adult partners and their children together with children from previous relationships.

Even though the social construction of families is becoming more diverse, not fitting in has real consequences. For example, when FEMA decides who qualifies for disaster relief, they say that only people who meet the U.S. Census definition of the family qualify for disaster recovery benefits. If your great aunt Mabel just happened to be visiting from Montana, she would not get benefits. Or if you had two nuclear families living in the same trailer that burned, only one might get assistance. We’ll look at this more in .

How we socially construct our ideas of family has real consequences.

A social problem must be addressed interdependently, using both individual agency and collective action

In the video that began our chapter, we saw two families making choices that increased their resilience.

Deciding who belongs in a family depends in part on individual agency. For example, you may argue with your partner about who will do the dishes tonight. On a wider scale, more dads participate in daily family life, as shown in figure 7.7. As of 2016, dads are 16 percent of all stay-at-home parents (Livingston and Parker 2019). Even though women still do the majority of childcare and housework, men are increasing their participation in parenting and childcare. (Livingston and Parker 2019). The change in involvement partially depends on individual families making daily choices about how to do the work of a family.

However, changes in belonging also depend on collective action. For example, early activism for gay and lesbian rights focused on recognizing and valuing all of the forms of family that queer people might experience. Because gay and lesbian people could not marry, adopt children, or make medical decisions for each other, activists marched in the streets to say that “All Families Matter” whether they were legally recognized or not. In 1996, Congress passed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which limited marriage to between one man and one woman. In many ways, this act solidified that marriage was a goal for queer people. Activism and legal challenges at the state level slowly won the right for same-sex couples to have civil unions and to marry (Goldberg 2015). On June 26, 2015, in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court ruled that the fundamental right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples. This combination of social movement pressure and legal action fundamentally changed the definition of marriage in the United States.

As we decide who belongs in a family or as a family, we take interdependent action as individuals and collectives to ensure that everyone belongs.

Licenses and Attributions for The Social Problem of Belonging: Who is Family

Open Content, Original

“The Social Problem of Belonging: Who is Family?” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“A social problem results from a conflict in values” is adapted from “The Family: A Socially Constructed Ideal” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 2e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modification: Added social problems language.

“Blended Families” definition adapted from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Collectivist,” “Individualistic,” and “Nuclear Family” definitions from Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 2e by Elizabeth B. Pearce, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.2. “Median Age at First Marriage: 1890 to Present” by the U.S. Census Bureau is in the Public Domain.

Figure 7.3. “Marriage for same sex partners worldwide 2021” by Our World in Data is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.4. “Photo of the Cleaver family” by ABC Television is in the Public Domain.

Figure 7.5. “People in the U.S. Living in Multigenerational Households Quadrupled between 1971 and 2020” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.6. “For children, growing diversity in family living arrangements” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Based on data from Pew Research Center.

Figure 7.7. “Photo of Dad and Daughter” by Humphrey Muleba is licensed under the Unsplash License.

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture

a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms

the social process whereby individuals that are taken to be different in some way are rejected by the greater society in with they live based on that difference

a biological categorization based on characteristics that distinguish between female and male based on primary sex characteristics present at birth

a family group that consists of two parents and their children living together in one household

a group who shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation

an ideal or principle that determines what is correct, desirable, or morally proper

a society that emphasizes the needs and success of the individual over the needs of the whole community

a society that focuses on meeting the needs and goals of all members of a group rather than focusing on individual successes

lacking a place to live

families consisting of two or more adult partners and their children together with children from previous relationship

shared understandings that are jointly accepted by large numbers of people in a society or social group

the phase of the emergency management cycle that begins with the stabilization of the incident and ends when the community has recovered from the disaster's impacts

the capacity of an individual to actively and independently choose and to affect change, free will, or self-determination

the actions taken by a collection or group of people, acting based on a collective decision

a person who does not conform to norms about sexuality and gender (particularly the ones that say that being straight is the human default and that gender and sexuality are hardwired, binary, and fixed rather than socially constructed, infinite, and fluid)