2.2 Social Identity and Social Location

Kimberly Puttman

As a member of society, you have both a social identity and a social location. A social identity conveys who you are to others. A social location describes your relationship to power and privilege in your society. Both social identity and social location use multiple dimensions of diversity.

2.2.1 Social Identity

Figure 2.2. White American sociologist Dr. Allan Johnson explores social identity and social location in his work.

A social identity consists of the combination of social characteristics, roles, and group memberships with which a person identifies. According to Johnson, shown in Figure 2.2, social identity is “the sum total of who we think we are in relation to other people and social systems” (2014:178). Our social identity includes the following attributes:

- Social characteristics: These can be biologically determined and/or socially constructed and include sex, gender, race, ethnicity, ability, age, sexuality, nationality, first language, and religion, among other characteristics.

- Roles: These indicate the behaviors and patterns utilized by an individual, such as a parent, partner, sibling, employee, employer, etc., which may change over time.

- Group memberships: These are often related to social characteristics (e.g., a place of worship) and roles (e.g., a moms’ group), but could be more specialized as well, such as being a twin, a singer in a choir, or part of an emotional support group.

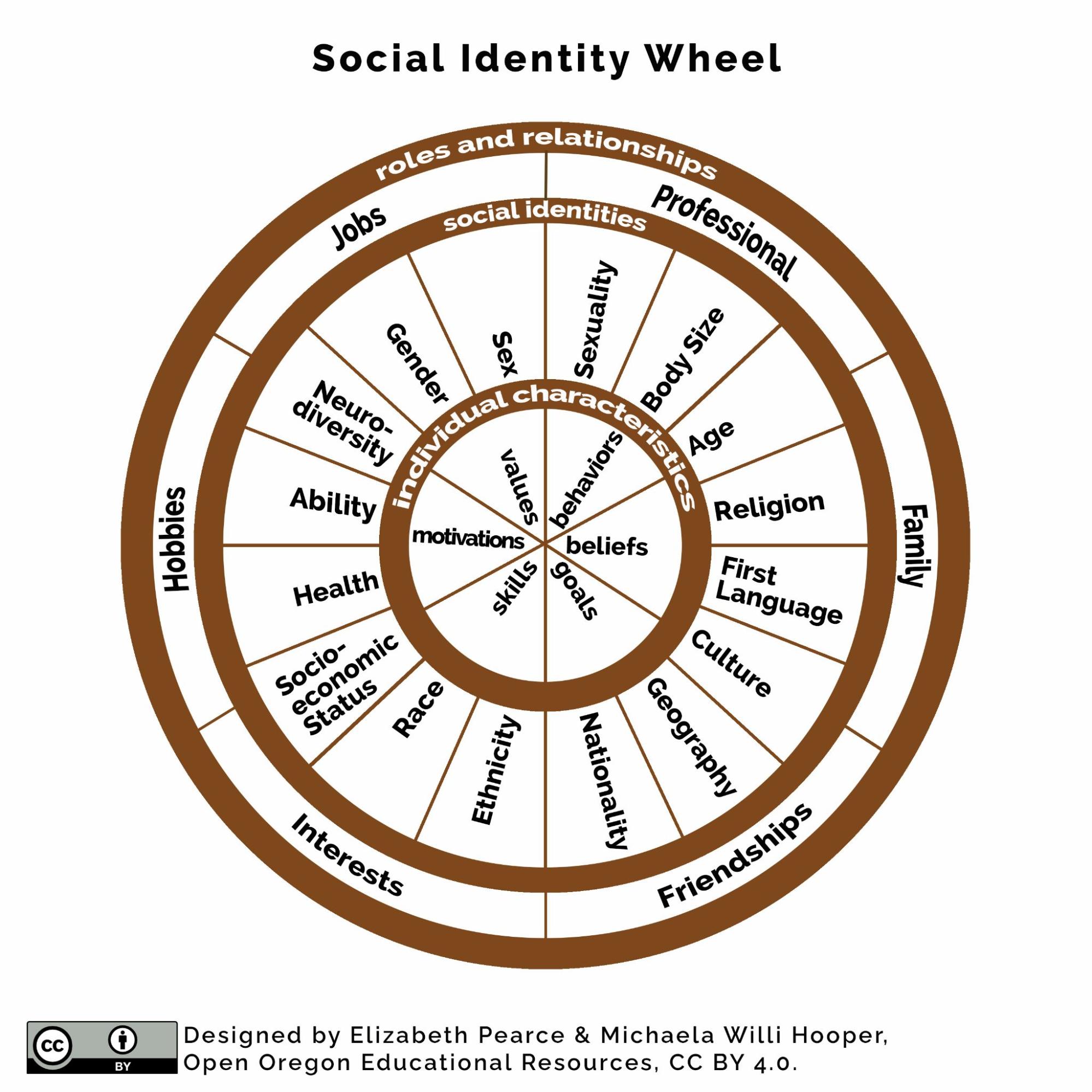

Figure 2.3. The Social Identity Wheel includes individual characteristics, social identities, and roles and relationships. How do you identify? Figure 2.3 Image Description

The social identity wheel in Figure 2.3 includes some common categories for social identity. The characteristics in the center of the wheel describe our individual characteristics. For example, we may value social justice or believe that building community is important. Our social identities also include social categories that describe us. The outside of the wheel includes our social roles and relationships. Each of us determines our social identity. We determine which of our social characteristics, roles, and group memberships are most important to our own identities. Other people in society may identify us differently, however. Sometimes, how we appear to others rdoesn’t match our personal lived experience.

The next sections examine how sociologists define these social characteristics.

2.2.2 Dimensions of Diversity

Groups of people can be diverse across many dimensions. This section defines the dimensions the sociologists commonly use to make sense out of social problems: race, ethnicity, gender, age, class, sexual orientation, and ability/disability. In other chapters, we will explore different dimensions of identity, including level of education, national origin or citizenship status, neurodiversity, and many other categories. As we look at specific social problems, we will use several of these identity dimensions to examine structural inequalities and individual experiences.

Race

Figure 2.4. Race is socially constructed but real in its consequences. In this picture of protest, Black people assert that “Nothing Matters Until Black Lives Do.” What do you think they mean?

One dimension of diversity we focus on is race, a socially constructed category with political, social, and cultural consequences based on incorrect distinctions of physical difference. Historically, race has been defined using observable physical or biological criteria, such as skin color, hair color or texture, or facial features. Today, scientists understand that the definition of race based on these biological characteristics is both wrong and harmful.

Human racial groups are more alike than different. In fact, most genetic variation exists within racial groups rather than between groups. We see differences in outcomes such as academic achievement or life expectancy based on race. However, these differences in outcomes are due to the racism embedded in economic, historical, and social factors (Betancourt and Lopez 1993), not in biology.

The concept of race itself is socially constructed. In the United States, if you have one drop of Black blood, you are considered Black. In contrast, Brazil measures five categories of race, mostly associated with skin color: black, brown, indigenous, white, and yellow (Monk 2016:413).

The meanings and definitions of race have also changed over time and are often driven by policies and laws. As we discussed in Chapter 1, this social construction has consequences. Black, Brown, and Indigenous people experience racism, a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produces and normalizes racial inequities (Kendi 2019). Because race, power, and inequality are linked, White people can experience racial bias but not racism. We discuss race in every chapter, but we explore the social construction of race more deeply in Chapter 9.

Ethnicity

Figure 2.5. Ethnicity: The US Census only recently asks you if you are “of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin? ” Why do you think this might be?

Ethnicity refers to a group of people with a shared cultural background, including language, location, or religion. Ethnicity is not the same as nationality, which is a person’s status of belonging to a specific nation by birth or citizenship. For example, an individual can be of Japanese ethnicity but British nationality because they were born in the United Kingdom. Ethnicity is defined by aspects of subjective culture, such as customs, language, and social ties (Resnicow et al. 1999).

While ethnic groups are combined into broad categories for research or demographic purposes in the United States, there are many ethnicities among the ones you may be familiar with. Mesoamerican refers to people whose families come from Central or South America. You may also hear Hispanic, Latino/a or Latinx as common terms that refer to people of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Spanish, Dominican, or many other ancestries. Asian Americans have roots in over 20 countries in Asia and India. The six largest Asian ethnic subgroups in the United States are Chinese, Asian Indians, Filipinos, Vietnamese, Koreans, and Japanese. If you want to learn more about the complexity of ethnicity for Asian Americans, review this report from the Pew Research Center. We’ll explore ethnicity more in Chapter 7.

Gender

Figure 2.6. Gender is both socially constructed and real in consequences. Depending on your gender identity, you may or may not have access to a public bathroom.

Gender is a social expression of a person’s sexual identity which influences the status, roles, and norms for their behavior. Gender differs from sex assigned at birth, a biological designation usually limited to female or male. We sometimes use the words gender identity or gender expression to clarify that we mean how someone does their gender, not their physical sex.

As a socially constructed concept, gender has magnified the perceived differences between females, males, and nonbinary people. The overreliance on gender categories has created limitations in attitudes, roles, and how social institutions are organized. We can see these limitations when we think about who can use which bathroom, as illustrated in Figure 2.6. We see the influence of gender when we look at what jobs we think are appropriate for women, men or nonbinary people. We notice it when we look at how parenting responsibilities and household chores are divided within families. Gender influences the distribution of power and resources, access to opportunities, and social control, including gender-based violence (Bond 1999).

Our understanding of gender also moves beyond the gender binary of female and male. Gender exists on a continuum. People now identify as gender-neutral, transgender, nonbinary or GenderQueer (Kosciw, Palmer, and Kull 2015). We’ll look at this continuum of identity more in Chapter 7 Unpacking Oppression, Queering Justice. We’ll examine gender and relationships to power in Chapter 12 Unpacking Oppression, Embodying Justice.

Age

Figure 2.7. Old women smiling. Being old is often stigmatized, but it’s not all bad. How does your age change your experience of the social world?

Some people say that age is just a number, specifically the number of years you’ve been on the planet. As you age, you experience developmental changes and transitions that come with being a child, adolescent, or adult. Sociologists group people based on their age. Age groups are made up of individuals regarded by society as holding a similar position based on their age. Power dynamics, relationships, physical and psychological health concerns, community participation, and life satisfaction can all vary for these different age groups. For example, baby boomers are retiring. Millennials often value meaningful, purposeful work over just making money. Generation Alpha is our newest generation, born after 2010. While it’s too soon to tell how Generation Alpha will make its mark, they will be shaped by planetary level social problems.

As each person ages, they experience different life stages. In the youth-focused culture of the United States, getting old can be something to be feared. However, as we look at the smiling faces of the older women in Figure 2.7, we see that sometimes getting old is a good thing. We’ll explore the relationship between aging and social problems more deeply in Chapter 13.

Class

Figure 2.8. A houseless person on the streets of New York walks beneath a sign for TUMI, a store that sells exclusive bags for travel. He carries several bags full of items. How does this picture demonstrate the inequality present in social problems?

Some social scientists believe that social class is the most important factor in determining how your life will turn out. A class is a group that shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation. Sometimes, social scientists will use the word socioeconomic status (SES) instead of class to emphasize that the classification includes factors related to money and cultural or social factors.

We can see the challenge of class in Figure 2.8, in which a person who is houseless is carrying all of his possessions, near a New York store selling expensive luggage. Our class affects our available choices and opportunities. This dimension can include a person’s income or material wealth, educational status, and occupational status. It can include assumptions about where a person belongs in society and indicate differences in power, privilege, economic opportunities, and social capital.

Social class and culture can also shape a person’s worldview, their understanding of the world. It can also influence how they feel, act, and fit in. It can impact the types of schools a child may attend, a senior’s access to health care, or an adult’s experience of work. The differences in norms, values, and practices between lower and upper social classes also impact well-being and health outcomes (Cohen 2009; Pearce 2020). We will explore social class more deeply in Chapter 6.

Sexual Orientation

Figure 2.9. Sociologists now understand that sexual orientation exists on a continuum. Many identities are possible. How do the changing labels around sexual orientation reflect the social construction of a social problem?

Sexual orientation refers to a person’s emotional, romantic, erotic, and spiritual attraction toward another person (Flanders et al. 2016). Sexual orientation exists on multiple continuums and crosses all dimensions of diversity (e.g., race, ethnicity, social class, ability, religion, etc.).

Sexual orientation is different from gender identity or gender expression. Over time, research on gay, lesbian, asexual, and bisexual identities has extended to other sexual orientations such as pansexual, polysexual, and fluid. (Kosciw, Palmer, and Kull 2015). We explore the social construction of sexual orientation more deeply in Chapter 7.

Ability/Disability

Figure 2.10. Disabled and Here. Physical ability and disability look different for every person. Can you confidently tell when someone is disabled? Figure 2.10 Image Description

Please take a moment to really look at the picture in Figure 2.10. All of these people are labeled as disabled. What do we mean when we use this label? In a medical model, a disability is a condition of the body or mind that makes it more difficult for a person to participate fully in everyday life (CDC 2020). These conditions may be visible or hidden, temporary or permanent. They can impact individuals of every age and social group. The World Health Organization states that about 1 in 6 people worldwide experience a disability (WHO 2023).

Traditional views of disability follow a medical model, primarily explaining diagnosis and treatment models from a pathological perspective (Goodley and Lawthorn 2010). Medical professionals and researchers see the person with the disability as “broken.” In this traditional approach, individuals diagnosed with a disability are often discussed as objects of study instead of complex individuals with agency.

A social model of ability views diagnoses from a social and environmental perspective. In the social model, the social problem of disability is that society doesn’t meet the needs of individuals with different abilities, not that the people are limited. A social model looks at all the social factors that might impact a person’s ability to fully participate in everyday life, not just at a particular impairment.

Defining disability or ability also depends on culture (Goodley and Lawthorn 2010). Culture may impact whether or not certain behaviors are considered sufficient for inclusion in a diagnosis. For example, cultural differences in assessing what is considered “typical” development have impacted the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in different countries. Culture may influence how people talk about their symptoms (Office of the Surgeon General, Center for Mental Health Services, and National Institute for Mental Health 2001). The experience of culture can significantly impact the lived experience of individuals diagnosed with a disability. We look at the social construction of ability and disability in Chapter 5.

These core social identities influence how you experience the world. They may change over time or stay the same. There may be other social identities that matter to you. Now that you have this basic understanding of the most important dimensions of social identities, we can explore why social identity matters in social problems.

2.2.3 Social Location and the Wheel of Power and Privilege

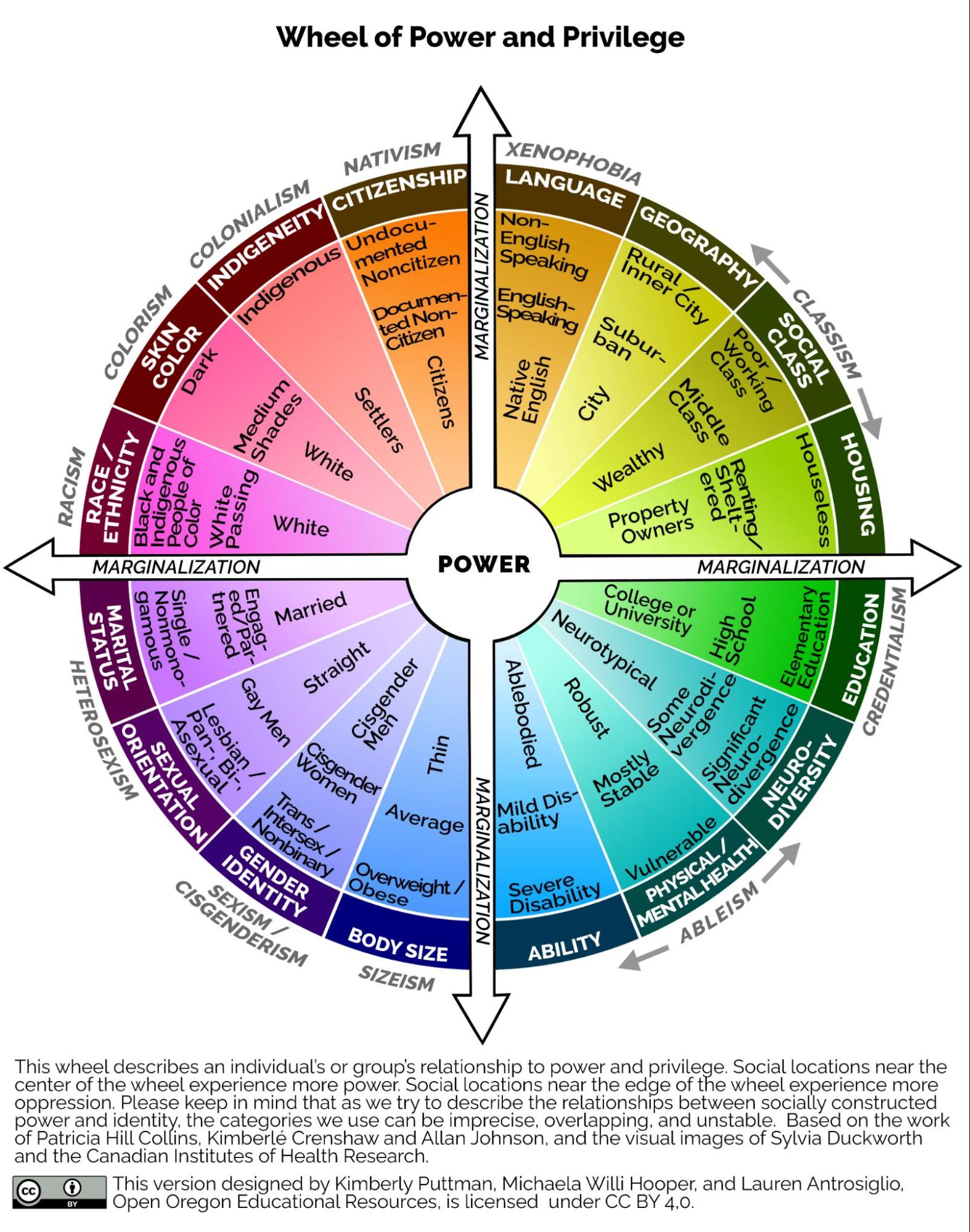

This Wheel of Power and Privilege shows the relationship between social identity and social power. When you examine this wheel, what do you see?

Figure 2.11. Wheel of Power and Privilege. Figure 2.11 Image Description.

Describing just one characteristic of a person’s identity is insufficient to understand them. Similarly, understanding any social group requires understanding their complex experiences. For this, we turn to the concepts of social location and intersectionality.

Social location is defined as the combination of factors including gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location, in relationship to power and privilege (Brown et al. 2019). In the circle in Figure 2.11, the word power sits at the center of the circle. People with characteristics near the center of the circle, such as White, non-disabled, property owners have more power and privilege. As you will remember from Chapter 1, power is the ability to sway the actions of another actor or actors, even against resistance. Privilege is “an advantage that is unearned, exclusive to a particular group or social category, and socially conferred by others” (Johnson 2018:148). People in the center are also known as people in the dominant group.

Non-dominant, or marginalized groups, are located at the outside of the wheel. Marginalization is a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are pushed to the outside of society by denying them economic and political power (Oxford Reference 2022). People in marginalized groups have less access to power. These social locations may include having only an elementary school education, being houseless, or being queer.

Rather than only being indicators of your identity, these social locations begin to describe the access that people in a group have to wealth, status, political power, economic stability, or other social resources. Identities that align with the groups who have power convey privilege. Those identities that align with less powerful groups experience oppression.

Citizens, for example, have the right to vote, the right to travel in and out of countries safely, and the possibility of applying for federal financial aid to finance school. They also have the right to work and receive government benefits like health insurance, social security, and unemployment. Citizenship itself conveys power to that social group. At the far end of citizenship, we find people who are undocumented, or living in a country without any citizenship rights. Undocumented people cannot vote, legally enter the country, or receive government aid to pay for education. Undocumented people may be deported at any time. Being safe where you live is a privilege. When you lack this safety, you experience a specific kind of oppression called nativism.

Figure 2.12. Bandages for people with dark skin became available in 2021. Can you find bandages, makeup, or athletic tape that works for your skin tone?

White privilege is one dimension of privilege. White sociologist Peggy McIntosh (Figure 2.13) writes, “I have come to see white privilege as an invisible package of unearned assets that I can count on cashing in every day, but about which I was “meant” to remain oblivious” (1989). If you want to dig deeper into these invisible privileges, see “White Privilege, Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” The Racial Equity Project adapts her work and defines White privilege as “the unquestioned and unearned set of advantages, entitlements, benefits and choices bestowed upon people solely because they are white” (MP Associations 2023).

Figure 2.13. White sociologist and feminist researcher Dr. Peggy McIntosh began to see her White privilege when she compared male privilege, which she could see because she experienced it, and White privilege, which she was unconscious of.

McIntosh lists twenty-six privileges, or unearned advantages, that White people have (McIntosh 1989). Here are some of them:

- I can if I wish arrange to be in the company of people of my race most of the time.

- If I should need to move, I can be pretty sure of renting or purchasing housing in an area which I can afford and in which I want to live.

- I can choose blemish covers or bandages in “flesh” color and have them more or less match my skin (the bandages in Figure 2.12 were introduced in 2021).

McIntosh makes White privilege visible. By listing circumstances in which White people receive benefits they may not notice, she describes inequalities based on race.

Recently, sociologist Allan Johnson expanded this discussion of privilege by applying it to gender, sexual orientation, and ability/disability categories in addition to race and ethnicity. He writes:

Many of these examples of privilege—such as preferential treatment in the workplace—apply to multiple dominant groups, such as men, whites, and the non-disabled. This reflects the intersectional nature of privilege, by which each form has its own history and dynamics, and yet they are also connected to one another and have much in common.

Also, consider how each example might vary depending on other characteristics a person has. How, for example, would preferential treatment for men in the workplace be affected by race or sexual orientation? Finally,remember that these examples describe how privilege loads the odds in favor of whole categories of people which may not be true in every situation and for every individual, including you….

- Whites who are unarmed and have committed no crime are far less likely than comparable People of Color to be shot by police, to be challenged without cause and asked to explain what they are doing, or subjected to search. Whites are also less likely to be tried, convicted, or sent to prison regardless of the crime or circumstances. As a result, for example, although Whites constitute eighty-five percent of those who use illegal drugs, less than half of those in prison on drug use charges are White.

- Heterosexuals and Whites can go out in public without having to worry about being attacked by hate groups. Men can assume they won’t be sexually harassed or assaulted just because they are male, and if they are victimized, they won’t be asked to explain their manner of dress or what they were doing there. (Johnson 2018:26-27, emphasis added)

Johnson’s list of privileges continues for multiple pages, highlighting how structures of society result in unearned benefits for some people and oppression for others.

You may respond differently to this model of power and privilege than someone else in your class. You may sigh with relief because you see the struggles you face every day in this model. You may be confused or uncertain. You may feel the model is complicated and hard to understand. You may be angry because you don’t see yourself as a victim or powerless. You may feel ashamed or “bad” for having privilege.

Any of these emotional reactions (and others not mentioned) are normal. Exploring these reactions is useful for two reasons. First, when you notice your reaction, you gain self-knowledge. The Wheel of Power and Privilege (Figure 2.11) is powerful, but it can be just colorful ink on the page if you don’t consider what it means. Understanding our own reaction to it helps us develop empathy for ourselves and for those we see as “other.” Second, these emotional reactions allow us to pause and take a breath before we react. This space between feeling and response allows us to choose an authentic and respectful response. Our response, even when it contains sadness, anger, or guilt, can connect us with others if we ask questions and listen respectfully to the answers.

The Wheel of Power and Privilege Describes Structural Oppression and Structural Privilege

In addition to any emotional reaction, though, the wheel of power and privilege model is useful in moving the conversation from the experience of one individual to structural experiences of oppression. This model explains systemic inequalities, not personal ones. Systems of law, education, business, medicine, and government are constructed with rules, policies, and practices that create a social world that is more powerful and more enduring than any one individual or group of individuals.

When you consider how changes in law change society, consider these examples. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. In 1967, in the case of Loving v. the State of Virginia, the US Supreme Court ruled that laws that prevented racial intermarriage were unjust. Until 1993, some states still had laws that rape could not occur within marriage because consent was already part of the marriage contract. In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled that the right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples.

These laws begin to reverse decades and sometimes centuries of racism, sexism, and homophobia embedded in our social policies, practices, and interactions. They expand social justice because they specifically name the structure of inequality and work to dismantle it. In every case, we have yet to realize the full freedoms and protections under these laws. The laws are one example of a social structure that conveys power unequally between groups.

The Wheel of Power and Privilege Measures Harm not Worth

You might have noticed the word marginalization on the wide white spokes of the Wheel of Power and Privilege. In everyday language, being marginal might mean being unimportant or worthless. However, sociologists use the word marginalized differently. Marginalized doesn’t mean “without value.” It means that a marginalized person lives within a system that harms them. To understand this more deeply, we need to explore what we mean by power.

When we consider the wheel of power and privilege, we are talking specifically about one type of power: power over. In this kind of power, a person, government, or institution can use laws, policies, coercion, or violence to change the behavior of another individual or group. For example, part of the definition of the government is that it is authorized to use force, like the police, the military, or prisons, to ensure social stability. In power over:

Power is seen as a win-lose kind of relationship. Having power involves taking it from someone else, and then using it to dominate and prevent others from gaining it. In politics, those who control resources and decisionmaking have power over those without. When people are denied access to important resources like land, healthcare, and jobs, power over perpetuates inequality, injustice, and poverty. (VeneKlasen and Miller 2007:n.p)

Power over is a common form of power, institutionalized with laws, policies, and practices. We can apply this to social problems when we consider that power and money are often related. People with money often determine which social problems get attention. Sociologist Rudolfo Álvarez points this out, writing:

How are social problems discovered by various groups in society . . . ? The answer, of course, is that a social problem comes into existence when a sufficiently powerful population becomes collectively aware of a condition it considers to be threatening to its well being and, consequently, sets out to alter those conditions so as to reduce the perceived threat. (Álvarez 2001)

This definition is unusual because it focuses on the use of power as a determining force in constructing a social problem.

Power with is a second kind of power. It is the power of people to make decisions together and take action. People and groups access this kind of power when they take collective action. We also see this kind of power in human relationships when intimate partners decide to create a life they both want. Power with involves dialogue, negotiation, and shared decision making (Berger 2005).

Protesters often use shared culture to create community with others, exercising power with. In one example, women in Chile danced in the streets to protest the disappearances of their husbands and children. Sting created a song that tells their story, sung in this video by Mercedes Sosa and Holly Near.

Figure 2.14 a and b. A) Argentine singer Mercedes Sosa and B) American activist Holly Near sing Danzan Solas/They Dance Alone

of 5:40 minutes. The song tells the story of women protesters in Chile who dance, telling the story of their husbands, children, and fathers who were murdered in Chile.

Danzan Solas/They Dance Alone

They’re dancing with the missing

They’re dancing with the dead

They dance with the invisible ones

Their anguish is unsaid

They’re dancing with their fathers

They’re dancing with their sons

They’re dancing with their husbands

They dance alone

They dance alone

It’s the only form of protest they’re allowed (Sting in Maluca 2018)

Ellas danzan con los desaparecidos

Ellas danzan con los muertos

Ellas danzan con amores invisibles

Ellas danzan con silenciosa angustia

Danzan con sus padres

Danzan con sus hijos

Danzan con sus esposos

Ellas danzan solas

Danzan solas

The song, Danzan Solas/They Dance Alone, is a contemporary protest song written by Sting and sung here by Mercedes Sosa and Holly Near. (Figure 2.14 a and b). The lyrics refer to the women, men, and children killed while protesting against the dictator Agusto Pinochet, who ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990. The song also laments the deaths of protesters in other Latin American countries who went missing because they dared to speak against the government. If you’d like to learn more about efforts to find these people in Chile, please explore this news article about current efforts. By using music to draw society’s attention toward injustice experienced by people with less political power and privilege, activists exercisepower with.

Power to is a third kind of power. It is the ability of any individual person to make choices in their own lives. This is the power we talk about when we see individuals making a difference. You may choose to vote or to leave an abusive relationship. In this case, you have power to. Your power to may be limited by oppression or inequality derived frompower over. In this book, power to is also called social agency.

Finally, power within is the fourth kind of power. This power comes from inside, when you know your own value and worth. When you respect yourself, you have power. One activist organization puts it this way:

Many grassroots efforts use individual storytelling and reflection to help people affirm personal worth and recognize their power to and power with. Both these forms of power are referred to as agency – the ability to act and change the world – by scholars writing about development and social change (VeneKlasen and Miller 2007:n.p).

We can applypower to and power with to the wheel of power and privilege. Any individual locating themselves on this wheel may take strength or pride in any of their identities. In fact, it is a sign of resilient mental health to accept and integrate all components of your identity. Movements such as Black Power or Gay Pride celebrate this acceptance. People who experience mental health issues find agency in telling their stories. Neurodiverse people champion a different way of thinking. As people age, they can savor the wisdom and wise seeing that can come from getting older.

Further, a group that experiences oppression may take back its power. The very characteristic that puts them outside the norm may be the identity that supports them in taking action. An oppressed group can sometimes more clearly see the changes needed to invest in health care that works for everyone, housing options so no one sleeps in the street, or family support that allows all members to thrive. The social location itself becomes a ground for change.

Figure 2.15. Activist Dolores Huerta, Nov. 10, 2015 speaking for Black Lives Matter, Immigrant Justice, and the Fight for $15. How does she use power with, power to, and power within to challenge power over?

Activist and author Dolores Huerta, pictured in Figure 2.15, reminds us that “the power is in your body” (Boyle 2017), and that all of us can protest. With Cesar Chavez, she organized the United Farm Workers Union. They organized a grape boycott, which convinced 17 million people to stop eating grapes. This power forced agri-businesses to negotiate with the workers to provide better wages, health and safety protections, and other rights. The fight is not over, but her rallying cry, “Si Se Puede/Yes We Can,” calls us all to act. If you’d like to hear from Dolores Huerta, herself, please watch Dolores Huerta: Labor Rights Icon on Standing up for Working People [Video] (11:18 minutes).

In the example of Dolores Huerta, Cesar Chavez, and the United Farm workers union, we see marginalized people leverage power with, power to, and power over to create change. In their example, we see that the wheel of power and privilege shows the harm of marginalization and not a lack of value, worth or agency.

The Wheel of Power and Privilege Demonstrates Intersectionality

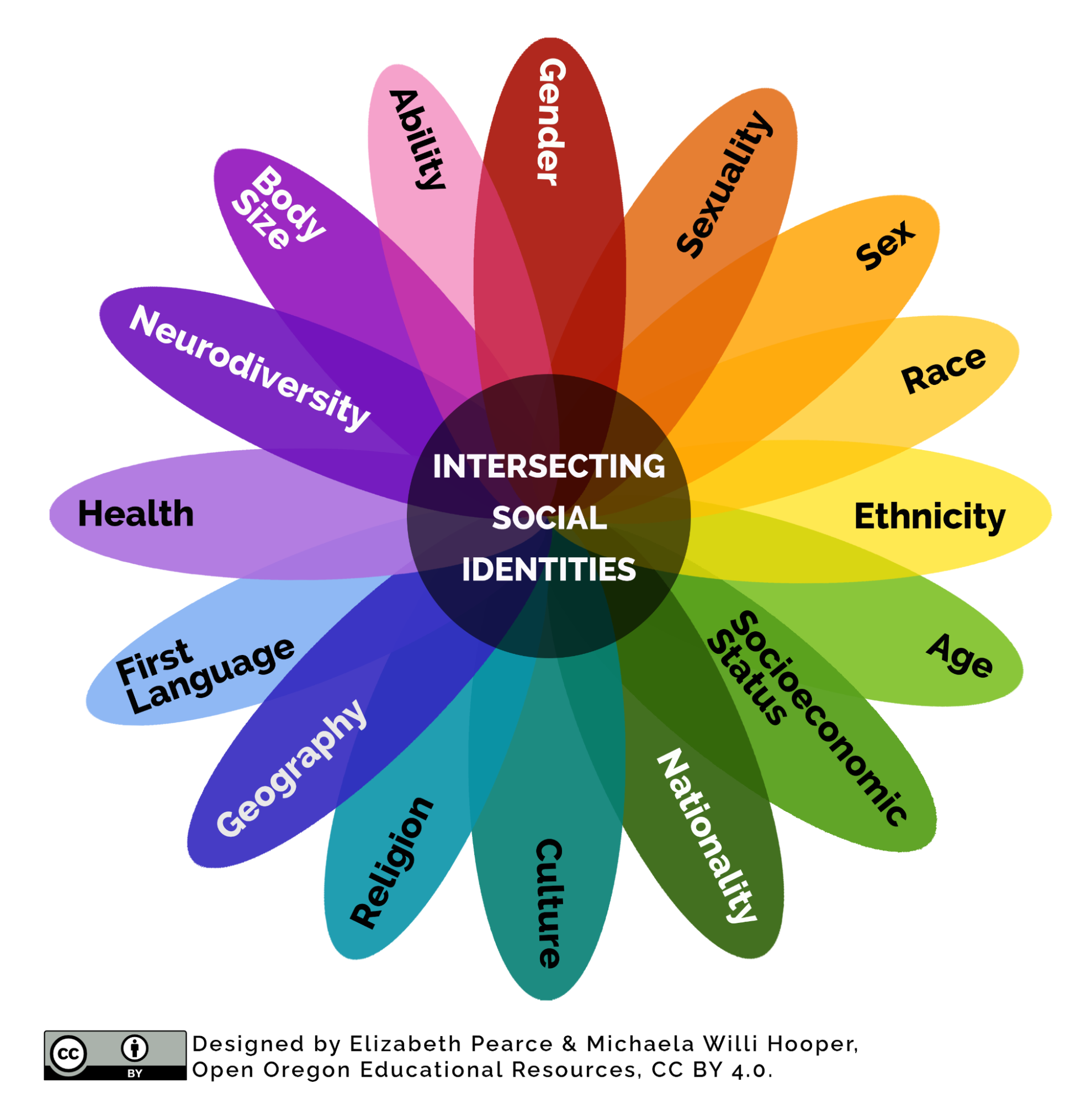

Figure 2.16. In this image of intersectionality, we can see that various social identities overlap creating intersectional identities for many people. Where do you fit? Figure 2.16 Image Description

As the Social Identity Wheel (Figure 2.3) and the Wheel of Power and Privilege (Figure 2.11) illustrate, social identity and social location are composed of multiple factors. Today, these multidimensional models are widely used to describe parts of society. Before the twenty-first century, many sociological models focused on one dimension of identity or location to discuss social issues. Single determinant models focused only on race, gender, class, or age as the most important explanation for a person’s experience. However, these models are insufficient.

Intersectionality is the idea that overlapping social identities produce unique inequities that influence the lives of people and groups (Crenshaw 1989). Social identities such as gender, race, or class don’t exist independently. Rather, they change a person or group’s experience in relationship to each other. This concept is illustrated in Figure 2.16. We see that social locations overlap.

Intersectionality studies have their origin in the Combahee River Collective. The collective was founded in 1974 by a group of Black feminist women in the United States who challenged how White feminists and leaders in the civil rights movement did not address Black women’s needs. They write:

The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives. As Black women we see Black feminism as the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneous oppressions that all women of color face. (Combahee River Collective 1978)

You have the option of reading the full Combahee River Collective Statement. These Black women see that the oppression of race, class, gender, and sexual identity are interconnected. They argue that we must understand these interlocking systems and work to dismantle them.

Unpacking Oppression, Intersecting Justice: Acting Intersectionally

Figure 2.17. Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw, Black lawyer, scholar, and activist, articulated the theory of intersectionality. How does using the lens of intersectionality increase the transformative power of our analysis and our actions toward social justice?

Articulated most recently by Black lawyer, scholar, and activist Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw (Figure 2.17), intersectionality asserts that race, class, gender, and other social locations must be considered simultaneously to understand any group’s relationship to power and privilege. Crenshaw exposes how gender and race have been historically divided into separate fields of study. Because of this division, “race” ends up referring to the experiences of men of color, the universal racial subject. Meanwhile, in studies of “gender,” White women are perceived as the universal female subject. However, we know that Black women have different experiences of discrimination and oppression than Black men or White women. Crenshaw writes,

Intersectionality is…a way of thinking about identity and its relationship to power. Originally articulated on behalf of Black women, the term brought to light the invisibility of many constituents within groups that claim them as members but often fail to represent them. (Crenshaw 2015)

To listen to Crenshaw in her own words, you may watch her recent talk which discusses the impact of intersectionality, 30 years after she popularized the term: Kimberlé Crenshaw at the 2020 MAKERS Conference

.

It’s your turn to unpack oppression and intersect justice:

This chapter links to three sources on Intersectionality. Read at least two of the following linked texts, then answer the questions below.

- The Personal is the Political

- Combahee River Collective Statement

- White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack

Questions

- How are these sources similar in identifying patriarchy or power with respect to women?

- How do they differ in discussing race?

- Where do you see intersectionality at work in any of these sources?

- How does using intersectionality strengthen our actions for social justice?

We’ll use the combinations of race, class, gender, ability, and sexuality to explore social problems. In Chapter 5, for example, we’ll examine how women of color experience d/Deafness. This kind of analysis is intersectional analysis.

2.2.4 Applying Social Identity and Social Location to One Life

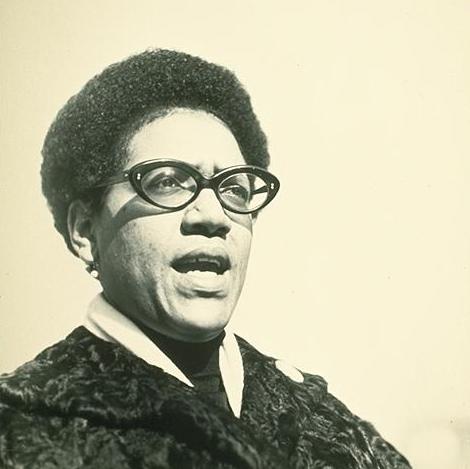

Figure 2.18. Audre Lorde self-described Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, and poet. I was introduced to her writing in college. She helped shape how I understand the power of my own integrated identity. Where do you find your power within?

My fullest concentration of energy is available to me only when I integrate all the parts of who I am, openly, allowing power from particular sources of my living to flow back and forth freely through all my different selves, without the restriction of externally imposed definition.

—Audre Lorde, self-described Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, and poet (Figure 2.18)

It can be challenging to move from the individual to community to social structure and back again when making sense of the social world. As a practice, I offer my own experience in the following section.

1.4.4.1 My Social Identity

My wheel of social identity comprises many social roles. Most relevant to this book, I am a writer. I teach sociology, GED, and English to Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL). I am an activist and a member of a healing community related to the Echo Mountain Fire. I am White, female, and at the time of this writing, 57 years old. I am a daughter and a sister. I am a wife in a long-term lesbian relationship. I am an ordained interfaith/interspiritual minister. I look forward to being able to sing in a choir again, and I am a beginning kayaker. Some of these identities have stayed consistent. I was born premature and have some hidden physical disabilities, for example. Other identities change over time. I look forward to my aging and the power that comes with being a wisewoman. Although I am wholly myself in all situations, some of the layers of my identity are core to how others see me.

My Social Location

My social location includes both experiences of oppression and privilege. I experience systemic inequality because of my queer identity. My love story with my wife is both beautiful and constrained by homophobic political systems. We fell in love in 2000, declaring our relationship to ourselves and our families late in that year. While this declaration was not without challenges, it required no state or government intervention to be real. What followed, however, was a decades-long struggle for legal, religious, and social legitimacy for our relationship. This struggle involved many institutions/governing bodies, as shown in the timeline in Figure 2.19.

Figure 2.19. This timeline shows the key actions which impacted Kim and Val’s legal and social status as an often and finally married couple. What are other changes in the legal recognition of social relationships?

As of 2023, we can be confident that our families and healthcare institutions will respect our need to be together if we are sick or require hospitalization. We expect retirement centers will allow us to live in the same room together if we can’t care for ourselves. Our money and our resources belong equally to both of us. Although we are not safe to be visible everywhere, worldwide, we love each other freely. We are grateful that we can live in relationship so openly, and yet, we also acknowledge that part of our struggle is the struggle against heterosexism, heteronormativity, and homophobia, components of social structure that confer rights and power to people who live and love in female/male relationships.

My Power, Privilege, and Intersectionality

While I am marginalized in my social location of queer, I also experience privilege as a White, educated woman. This privilege supports me in softening the impact of queerness. Because I can live where I choose, I can choose a community and physical location that is beautiful, restorative, and safe. Because I am well educated I can find work that I enjoy and that pays well. My education and professional work experience resulted in digital fluency, so I can find communities locally and online that nourish the various layers of my identity. Although I’ve worked hard, many of these privileges are unearned.

This combination of power and marginalization, when applied to social groups, is what Crenshaw points out in her work on intersectionality. Race, gender, sexual orientation, or class alone can not completely define how someone experiences the social world. Instead, combinations of race, class, gender, age, and origin interact in a complex matrix of power and privilege to create your experience.

My Identity and Agency

Figure 2.20. Val and Kim at Women’s March in Newport Oregon, Jan 21, 2017 (with coffee because we live in Oregon).

When you look at our relationship timeline, it is obvious that Val and I experience systemic inequality. Straight people who choose to marry don’t usually need multiple ceremonies in order to have the government or their house of worship validate their relationship. However, my queer identity is also a source of my personal power and my individual willingness to take action. Like many feminists of the 1970s, Val lived “the personal is the political” (Hanisch 1968) when she knocked on her neighbors’ doors. If you want to learn more about this concept, explore Carol Hanisch’s paper (Hanisch 2009). By telling them that she was a lesbian, orcoming out, she challenged their assumptions that to be lesbian was to be strange, deviant, or dangerous. We found great joy in singing with lesbian choirs over many decades. My experience as a lesbian is steady fuel for my commitment to personal authenticity, empathy, and social justice (Figure 2.20).

2.2.5 Licenses and Attributions for Social Identity and Social Location

Open Content, Original

“Social Identity and Social Location” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 2.3. “Social Identity Wheel” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.11. “The Wheel of Power and Privilege” by Kimberly Puttman, Michaela Willi Hooper, and Lauren Antrosiglio, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.16. “Intersecting Social Identities” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.19. “Val and Kim Get Married” by Kimberly Puttman and Valerie McDowell, Open Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Social Identity” and “Dimensions of Diversity” are adapted from “The Social Construction of Difference” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 1e, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications: Summarized some content and applied it specifically to social problems.

“Class” definition from Introduction to Sociology 3e by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Ethnicity,” “Gender,” and “Role” definitions are adapted from Contemporary Families in the U.S.: An Equity Lens 2e [manuscript in press] by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Open Oregon Educational Resources, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Section on Intersectionality is adapted from:

- “Levels of Analysis” by Aimee Samara Krouskop, Social Change in Societies [manuscript in press], Open Oregon Educational Resources, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- “Social Theory Today” by Matthew Gougherty and Jennifer Puentes, Sociology in Everyday Life [manuscript in press], Open Oregon Educational Resources, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.2. “Allan Johnson” by Washington State University is licensed under CC BY-SA 1.0.

Figure 2.4. “Photo” by nappy is in the Public Domain, CC0 1.0.

Figure 2.5. “Photo” by Rajiv Perera is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 2.6. “Photo” by The Gender Spectrum Collection is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 2.7. “Photo” by Artyom Kabajev is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 2.8. “Photo” by Nate Johnston is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 2.9. “Photo” by nappy is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Figure 2.10. “Photo” by Chona Kasinger, Disabled And Here is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.14a. “Mercedes Sosa in Heredia (Costa Rica). March 1st 2008” by Marta Molina, Wikipedia is licensed CC BY SA 2.5.

Figure 2.15. “Dolores Huerta” by Susan Ruggles is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 2.17. “Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw” by Heinrich-Böll-Stiftun is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.18. “Audre Lorde” by Elsa Dorfman is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Applying Social Identity” and related figures except 2.19 are all rights reserved. Please request permission to re-use the author’s personal story.

Figure 2.12. “Photo” from “The Story Behind BAND-AID® Brand OURTONE™ Adhesive Bandages” © Johnson & Johnson is included under fair use.

Figure 2.13. “Photo” of Peggy McIntosh © The SEED project is included under fair use.

Figure 2.14b. “They Dance Alone/Ellas Danzan Solas” by Holly Near is licensed under the Standard YouTube License. Partial lyrics are included under fair use.

Figure 2.20. “Photo” © Kimberly Puttman is all rights reserved.