1.3 What Is a Theory?

A theory is an idea that helps people make sense of what they are seeing. For example, with crime in Portland, Oregon, during the pandemic, one theory may try to explain why a bunch of kids home from school for a long time, who live in the same neighborhood, and who all have tough home lives may come together and act out in violent ways. Later, this book discusses specific theories that attempt to explain such a situation. However, for now, let’s start with the basics.

The Open Education Sociology Dictionary defines theory as:

- a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomenon are related to each other based on observed patterns.

In other words, a theory is an attempt to explain what is happening. In criminology, that means explaining what is happening in terms of crime and criminal behavior.

Even with knowing the official definition of theory, it seems like just about anyone can come up with a possible explanation for what is happening and claim it is a legitimate theory. Sure, anyone can technically come up with a theory to explain some phenomenon, but not everyone can be right.

1.3.1 Where Theories Come From

How do we come up with theories in the first place? We start with a question. Why is what we are witnessing happening? Why is gun violence increasing? How can we explain this phenomenon? We create an educated guess based on what we have seen, called a hypothesis. This hypothesis is a reasonable possible explanation of why we think this phenomenon is occurring. It is not random. It must fit with what we are seeing, and it must be simple enough that we can test it to see if we are onto something. It is the beginning of a theory.

Remember, as criminologists, we focus our theories on the why of crime. That means all the criminological theories you will read about in this book will attempt to explain what causes crime to occur. If we can understand it, we can predict it, and if we can predict it, we can prevent it. Theories also recognize, however, that some reactions to crime in our criminal justice system or by society may actually cause more crime. This creates a negative cycle that makes it even more difficult to intervene and prevent crime.

1.3.2 Causes, Crimes, and Consequences

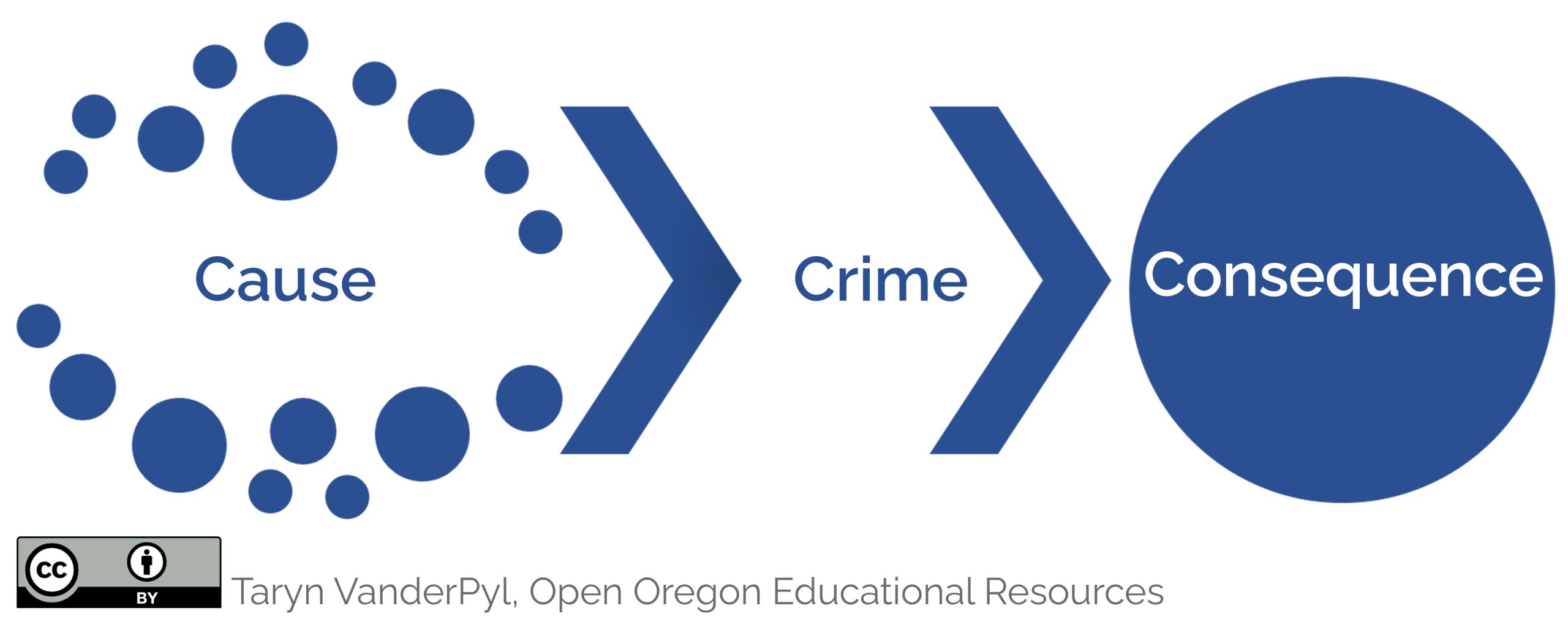

When we recognize all the factors that can cause crime, we go from a simple straightforward view of crime like we see in figure 1.3 to the far more complex and complicated understanding of criminal behavior as a whole seen in figure 1.4. Criminology says that we are more likely to make matters worse and perpetuate crime if we do not address the original causes. A focus on consequences can lead to more causes, which leads to more crime, which leads to more causes as consequences, and the cycle continues.

Figure 1.3 Straightforward View of Crime.

Figure 1.4 Complex View of Criminal Behavior.

1.3.3 Foundation of Criminological Theory

Criminologists’ work is guided by theories created by criminologists who went before them. Several criminological theories attempt to explain why people commit crimes. Why are there so many? How do we know which one is right?

Criminology is a different kind of science than, say, biology. We cannot put crime under a microscope and examine it as you see in figure 1.5. We cannot change one variable and see what happens on the slide. Criminology is dynamic and involves a lot of different perspectives of people who do not always agree on what they are seeing.

Figure 1.5 Scientist Examining Sample on a Slide Under a Microscope.

For this reason, we must be aware of potential biases that affect how we see what we think we see. Politics can provide a useful example of how different perspectives can change the way we look at something. The table in figure 1.6 compares just some of the major beliefs of the top three political parties in the United States. Consider how each different political party might view the causes of crime, appropriate punishments, and prevention strategies. How could these political beliefs influence theories?

| Republican Party | Democratic Party | Libertarian Party | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Conservative | Liberal | Individual |

| Economic | Wages set by free market; everyone pays the same tax | Livable minimum wage; higher taxes for the wealthy | Wages set by free market; there should be no taxes |

| Social | Individual rights and justice | Community and social responsibility | Individuals should each take care of themselves |

| Government | Government regulations get in the way of capitalism | Government regulations protect citizens | Government should stay out of everything |

| Crime | Tough on crime, long sentences, focus on punishment | Criminal justice reform, focus on rehabilitation | Limit what is considered a crime and only protect individual rights to life, liberty, and property |

Figure 1.6 Comparison of Republican, Democrat, and Libertarian Stances.

Because criminology as a science can be more subjective than natural sciences like biology and more open to biases, we must be even more vigilant. For this reason, any claims of a new theory must go through multiple levels of evaluation before they are to be considered valid.

1.3.4 From Research to Knowledge

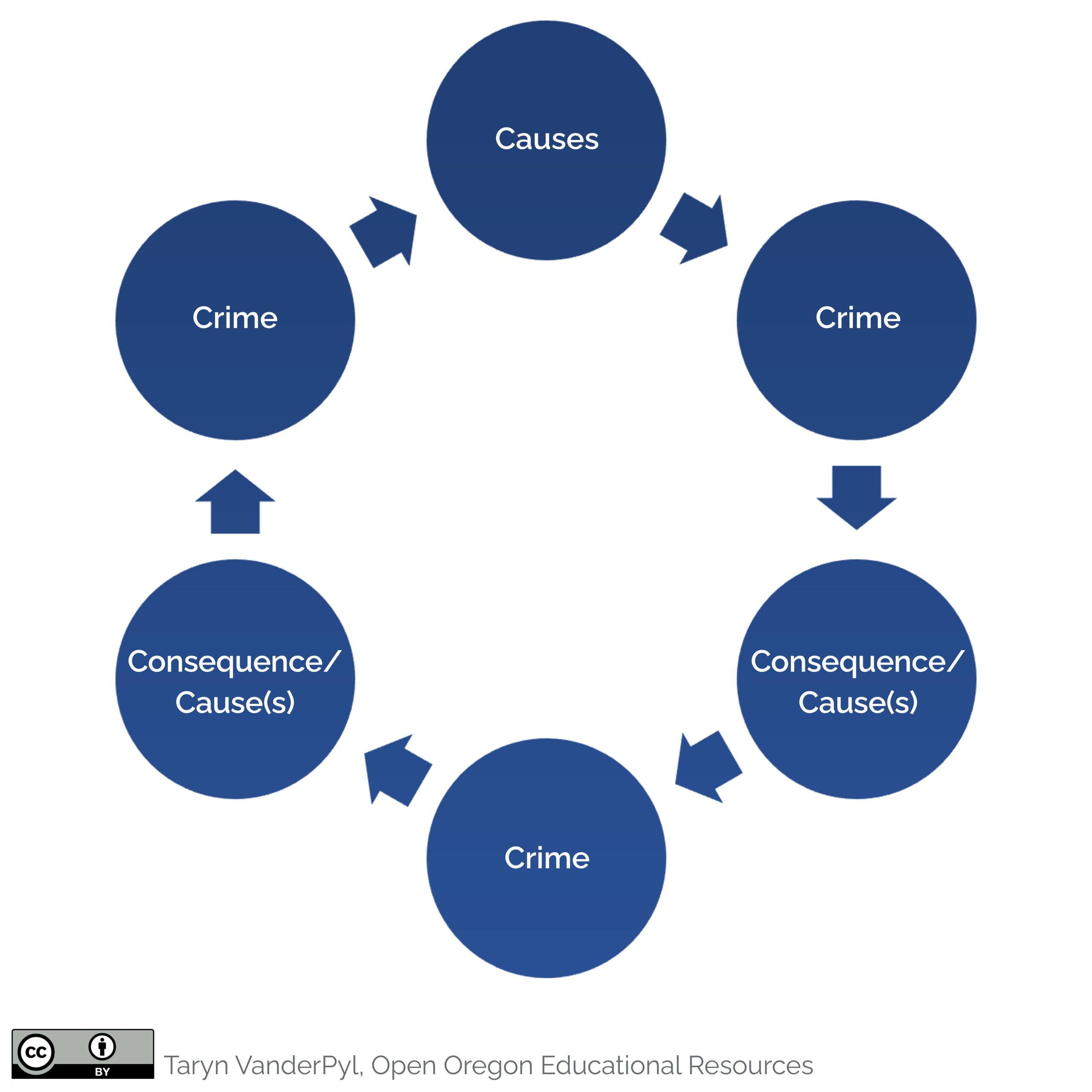

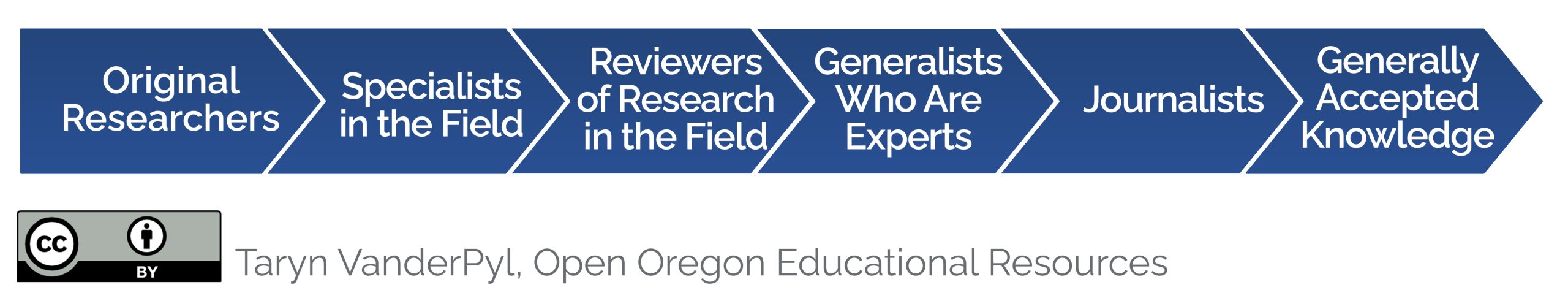

David Krathwohl, an educational psychologist and social science researcher, created a step-by-step guide for how to design, implement, and evaluate research in social sciences like criminology. Krathwohl’s guide uses a chain of reasoning and accountability that looks like the scales of a fish (1993). He explains that the process of moving from research findings to accepted knowledge requires a lot of steps, time, and people.

In his fish-scale analogy, Krathwohl (1993) says that findings start with the original researchers, and then the results are examined by specialists in the field. Once the results make it through the specialists, the research findings and claims are evaluated by reviewers of research in the field. Next, the information is expanded beyond the specific field out to generalists who are experts in the area and are able to judge the value of the research and claims. Getting through all these steps is a major accomplishment.

Figure 1.7 Process of Moving from Research Findings to Accepted Knowledge.

Once making it through this tough gauntlet, the research findings may get picked up by journalists who spread the word out to the general public. Most research never makes it this far. Think about any time the news references research in their stories. It doesn’t happen that often when you think about how many stories they cover every day. Once someone’s research findings and their claims make it this far in the process, it becomes generally accepted knowledge, and they are more likely to be believed.

Each of the steps of this long process has multiple people and if you think of each person in each step as a fish scale and each fish scale piling on to the ones behind and beside it, you end up with layers and layers of what come to look like the skin of a fish (figure 1.8). It takes a lot of fish scales for someone’s research and claims to become accepted. Then, as research findings become accepted knowledge, theories may be created based on the study or formed as a result of a collection of studies finding similar results.

Figure 1.8 Fish Scales.

1.3.5 Criteria for Criminological Theories

Ronald Akers and Christine Sellers (2013) established a set of criteria to guide criminologists in evaluating theories. They said a “good” criminological theory must have these six criteria:

- logical consistency

- scope

- parsimony

- testability

- empirical validity

- usefulness

Logical consistency is the most basic element of any theory. In other words, it must make sense. Is it reasonable? Does it make sense from beginning to end? That would make it both logical and consistent, giving it logical consistency.

Scope refers to what all is covered or addressed by this theory. Does it apply across gender identities? How about different types of crimes? Are both adults and juveniles covered? The wider the scope, the more the theory explains. The more a theory can explain (while still meeting the other five criteria), the better it is.

Parsimony means simplicity. Parsimony may seem strange coming after scope since they seem to mean the opposite. A parsimonious theory is clear, concise, elegant, and simple. It does not try to explain too much. We do want that big scope, but only if it is simple and makes sense. Scope and parsimony are not contradictions. They are complementary when done correctly.

Although we cannot examine our theories through a microscope, they must still be testable. When a researcher tests a theory, they are basically trying to prove it wrong or falsify it. That is not a bad thing; it is a good thing. Every theory must be open to possible falsification because the more it is tested, the stronger it becomes. If someone falsifies a theory, they also find what makes it more accurate and that finding updates the knowledge base upon which the theory is built. Once that is done, it is tested again. And again. And again.

After many tests through a variety of approaches to research, the theory ends up stronger than ever and is supported by evidence from each test or study. This evidence gives the theory empirical validity, which means we can see it in research (empirical) and we are seeing what the theory claims we will see (validity). In other words, we see evidence in research that confirms the claims of the theory.

Finally, usefulness refers to the notion of what we then do with what we know. The theory should be applicable to real life. Since our whole goal is to learn more about the why of crime, then a criminological theory should be useful in that it tells us what to do in real life to interrupt the criminal patterns it addresses.

This can only happen when we know for sure that we are all talking about the same thing, especially when what we are talking about is so abstract.

1.3.6 Operational Definitions

How do we test something abstract that cannot be observed in a microscope? We have to make it not so abstract. Let’s say a theory claims grand romantic gestures cause people to fall in love. First, we need to know exactly what is meant by a grand romantic gesture. We also need to figure out how to know if someone has actually fallen in love.

Let’s start by defining “grand romantic gesture.” A definition such as this is an operational definition, which allows us to measure and test the concept we are describing so we know exactly what we are looking at and what we are looking for.

For example, grand romantic gestures for the sake of this research study can be defined as the use of a flash mob to invite someone on a date or trailing a banner asking for a date behind an airplane (figure 1.9).

Figure 1.9 Flash Mob.

By narrowing down grand romantic gestures to just these two specific actions, the research can be targeted. There is no confusion about what is being used to cause something else to happen. The next challenge in this example is figuring out how to measure whether the person on the receiving end of the grand romantic gesture falls in love. That is more than we can get into in this chapter—we all know love is more complicated that what can be cleared up in one book.

For another example, what if we have a theory that says someone who commits crime has a low level of self-control? How can we test that theory? First, we have to operationally define the two concepts named in this theory: committing crime and a low level of self-control. What crimes are we talking about? Murder? Assault? Burglary? Vandalism? That’s quite a range that we need to define according to what is claimed in the theory. Also, if there is a low level of self-control, then that means there are other levels, too, like high or medium levels of self-control. How do we define those levels and how do we know someone’s level? How can that be tested and identified? What is our operational definition of self-control and how is it measured and divided into different levels?

There are whole classes and textbooks on this issue alone and how to do this type of research responsibly and scientifically. For now, let’s just talk about it broadly.

1.3.7 Variables and Spuriousness

The two concepts of crime and self-control from the previous example are variables in this type of research. We are testing these two variables (which are concepts, factors, or elements in the study) to see what sort of influence one has on the other. How should they be tested?

We could test someone’s self-control by exposing them to a temptation (like a donut), telling them they are not allowed to have it, leaving the room so they are alone with the temptation, and then seeing if they go for it anyway (figure 1.10).

Figure 1.10 Temptation Donuts.

We could test criminal behavior by looking at that same person’s criminal record. Will we see that the same people who jumped at the temptation also have criminal records? Does that show us that someone who commits crime has a low level of self-control? Could we then say these two variables appear to be correlated (related)? Others would then come along and test our two variables (concepts) in different ways to see if the results are the same. Every time this happens, we learn even more about the relationship between crime and low levels of self-control, and we learn more about this proposed theory.

One snag could be a third variable coming into play that we missed or ignored. Is it low self-control to give into the temptation, or was there another factor that made the subject cave? Also, what if the temptation we chose was not actually tempting to every participant in our study in the same way? What if someone is really hungry or has been dieting and maybe craving a donut? What if some participants don’t really like donuts or they just had a big lunch? In fact, there could have even been a third variable that is completely unrelated that caused both the appearance of low self-control and the crime. When that happens, it is called spuriousness. Spuriousness is when a third variable is causing the other two.

For example, research shows that ice cream sales and murder rates are positively correlated (figure 1.11; Cohen, 1941; U.S. Department of Justice, 1969; Peters, 2013). This means that when one goes up the other also goes up—when ice cream sales go up, murder rates also go up and vice versa. At first glance, someone may claim that ice cream is causing people to commit murder or committing murder makes people hungry for ice cream. However, what do you think might be a better explanation? Can you think of a third variable that might cause ice cream sales and murder rates to both increase?

Figure 1.11 Family Enjoying Ice Cream.

Let’s look just at Oregon as an example. Consider the weather and what happens in summertime in Oregon. Thankful for the sunshine after months of rain, a lot more people are outside. Also, many homes in Oregon do not have air conditioning, so people may be more comfortable outdoors during heatwaves. A common activity during hot periods is to eat ice cream. It is cold, refreshing, and delicious—thus we see an increase in ice cream sales.

In some areas, more people outside leads to more conflict. This is especially true in areas with a lot of gang activity. Are gang-related murders more likely to happen when it is cold and the group is holed up hanging out inside someone’s garage or when it is warm out, and they are out and about, possibly encroaching on a nearby gang’s territory? When we consider how warm weather changes people’s behavior in this overly simplified example, it is possible to see that the weather itself can be a factor in both an increase in ice cream sales and an increase in murder rates and that ice cream and murder are actually in no way related. That is spuriousness.

All the criteria discussed here are important for making a good theory, but there is one last thing to consider. What’s the point? A criminological theory needs a purpose. A good criminological theory will help guide policies and practices to prevent or reduce crime. For example, a theory that connects childhood trauma to an increased likelihood of delinquent behavior in adolescence tells those working with at-risk youth that they may be able to prevent some offenses by intervening with kids to protect them from trauma or help them work through what they have experienced.

1.3.8 Licenses and Attributions for What is a Theory?

“What is a Theory?” by Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.3 Straightforward View of Crime by Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.4 Complex View of Criminal Behavior by Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.5 Photo of Observing samples under the microscope by Trust “Tru” Katsande. License: Unsplash License.

Figure 1.6 Comparison of Republican, Democrat, and Libertarian Stances by Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.7 Process of Moving from Research Findings to Accepted Knowledge by Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.8 Photo of Fish scales is in the Public domain.

Figure 1.9 Photo of Flash Mob by DMatUFWiki, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1.10 Photo of Delicious Donuts by Kobby Mendez, License: Unsplash License.

Figure 1.11 Photo of Liam and Isaac eating ice cream at Will’s Batch, Elsternwick, Julia by Alpha, CC BY-NC 2.0, via flickr.