4.3 Social Structure Theories

Structural functionalism in sociology explores the ways in which different parts of the community interact with each other. A structural functionalist sees that the existence of a social structure provides a continuous benefit to society. For instance, if the educational system is strong, society thrives. If the educational system is weak, society suffers. The weakened system results in social issues, such as crime and poverty. Durkheim is considered a structural functionalist who has influenced theorists to look at the strength of the social structure to determine the health of society.

4.3.1 Conflict Theory

Figure 4.2 Max Weber, 1918.

German Sociologist Max Weber (figure 4.2) studied the conflicts between social groups in the early 1900s. Social groups are created by economic forces (similar social class, income level, types of employment); by social forces (similar values and beliefs); and by political forces (levels of social status and power, honor or prestige, respect). These differences can lead to the creation of interest groups that join forces to exercise power or influence.

Weber believed conflict among these social groups was inevitable, which is the basis for what he called conflict theory. He argued the authority figures in society are religion, business, government, and the law. These are not going to have the same interests, priorities, or goals as all social groups thereby creating conflict between those who benefit from the rules. Furthermore, those who do not benefit from the rules are likely to be exploited, discriminated against, and marginalized. For this reason, there will be conflict between social groups and that leads to criminal or deviant behavior.

4.3.2 Twists on Conflict Theory

Weber’s conflict theory was an expanse of Karl Marx’s (1848) philosophy about economic conflict. Marx saw conflict originating in his version of the “haves and have-nots.” He blamed capitalist society for creating great wealth for a select few and extreme poverty for many others. He saw the capitalists as owning the means of production (businesses) and the proletariat (workers) as the group that is exploited through their labor. Marx saw this natural conflict that he believed would create class wars and revolution as the workers replaced the capitalists. As we know, there are still “haves and have-nots” and a giant gap between the wealthy and the rest of us, so the workers have still not replaced the capitalists. However, that does not mean there has not been conflict.

Around the same time as Weber, Dutch criminologist Wilem Bonger was also building upon Marx’s claims. Bonger connected capitalism as argued by Marx to the promotion of greed and self-interest that he referred to as excessive egoism. He, like Marx, viewed capitalism as the core problem. Bonger argued the poor commit crimes out of need or a sense of injustice when they are pushed by the inequalities that exist within a capitalistic system. He did not claim that poverty by itself caused crime. Rather, when poverty was merged with negative social forces such as racism, individualism, and materialism, these conditions would be very conducive to the rise of criminality.

Another twist on conflict theory came from Swedish-American sociologist Thorsten Sellin. He studied the role of culture conflict in causing crime (1938). Sellin saw behavioral norms as expressions of group cultural values. In a homogenous society, where everyone’s the same, there is a consensus on what is right and what is wrong. But in a heterogeneous society with cultural differences, conflict may exist regarding what is right and wrong. Sellin said when the values and beliefs of two different groups collide, culture conflict results.

4.3.3 Strain Theory

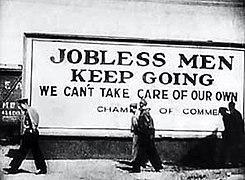

Figure 4.3 Unemployed men during the Great Depression.

It has been said that sociologist Robert Merton “Americanized” Durkheim’s anomie theory. Merton (1957) argued that U.S. society considers economic success as an absolute value, hence the “American Dream.” As a result, the pressure to achieve economic success overrides any need to fit in with the rest of society’s rules and follow their laws.

In American society, there is a widely acknowledged goal of some level of wealth that tends to be represented by home ownership, two cars in the driveway, a picket fence, and a dog (probably a golden retriever). However, being able to get this “American Dream” is actually not possible for a lot of people. The general message is to work hard, follow socially accepted steps toward your goal, and you will be rewarded. This does not work out in reality for many Americans and the distance between what someone wants to achieve and what they are actually able to achieve because of various obstacles and limitations is strain (figure 4.3).

Merton’s strain theory is that when someone faces strain, they experience anomie which Durkheim explained as the relative absence or confusion of norms and rules in society. When applied to strain theory, anomie is the willingness to take alternative routes or use alternative means to get to the goals you want. In other words, if a big television is a symbol of success and happiness, someone may be willing to steal one if they cannot afford to buy one so people think they are doing well.

Merton witnessed this phenomenon firsthand during the Great Depression. He saw that people still valued American culture and its focus on economic success but access to legitimate opportunities to reach that success was extremely limited. When confronted with the contradiction between culturally accepted economic goals and socially accepted (and limited) means of achieving success, many Americans experienced anomie and that contradiction produced strain.

How does someone respond to this strain? The majority, according to Merton, accept their reality and conform by accepting that they need to accept lower goals that can be achieved through legitimate means. They achieve their own level of success within the rules of society even if they never reach their aspired goals. However, not everyone is willing to adjust their goals, especially when being bombarded with constant messaging that they need more through social media, music, advertisements, television shows, movies, etc.

4.3.4 Social Disorganization Theory

Figure 4.4 Chicago 1930s.

For the sociologists at the University of Chicago, the diverse city was a perfect setting to test their theories, leading to several new approaches to understanding crime in urban settings. One popular theory that came out of the Chicago School is the social disorganization theory.

Sociologists Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay (1942) applied some knowledge gained by other scholars at the school to their own examination of tracking crime in certain Chicago neighborhoods. They looked at Chicago’s geographic distribution of crime and delinquency and found that areas of high crime were also characterized by weak community controls. Social disorganization theory claims that neighborhoods with weak community controls caused by poverty, residential mobility, and ethnic heterogeneity will experience a higher level of criminal and delinquent behavior.

The neighborhoods they studied that had consistently high crime rates consisted of mostly low-priced or subsidized rental properties, a large portion of the residents being on public assistance, and high rates of unemployment. This setting of poverty meant that those who stayed living in that area long-term were those who had no choice, versus those who moved out as soon as they gained some financial stability. Leaving at the first chance they got was the cause of high residential mobility.

There was also a steady stream of new people moving into the neighborhood as they moved to the city or were no longer able to stay in their previous neighborhoods. As a result, there was constant movement in and out of the area with no one considering it home or making any investment in the area. Such an investment would otherwise create a sense of community. However, these neighborhoods were marked by high ethnic heterogeneity coupled with high residential mobility, so for the time people lived in the area, they socialized with and helped only people within their limited comfort zone of shared ethnicity. There was no community building or getting to know others in the neighborhood, which is usually the source of informal social controls (keeping an eye on each other’s kids). The frustration of growing up in such a neighborhood could also fall within the general strain theory.

4.3.5 General Strain Theory

American criminologist Robert Agnew expanded Merton’s strain theory to include short-term frustrations as possible causes of strain in an adolescent’s life. In general strain theory, Agnew argued that social injustice or inequality may be at the root of strain instead of just the search for the American Dream (1992). Agnew would point to that negative interaction as a possibility of strain in an individual’s life, particularly with adolescents. The feeling that the deck is stacked against them and there is no reason to even attempt to live by society’s rules can lead an individual to criminal or delinquent behavior. Delinquency, according to Agnew, becomes a natural reaction to the stresses of adolescence.

Merton’s theory of strain depicted individuals working toward an unattainable goal, but Agnew’s theory suggests that some individuals are running away from something instead. This may include punishment by their parents or negative relationships that exist at school. According to Agnew (1992), adolescents are “pressured into delinquency by the negative affective states – most notably anger and related emotions – that often result from negative relationships.”

Agnew identified three distinct types of strain for adolescents:

- the failure to achieve positively valued goals;

- the removal or loss of something valued by the individual (suspension from school, relationship breakup, death of a family member, divorce); and

- the presence of negative stimuli (child abuse, victimization, negative school experiences).

All juveniles will experience at least one of these types of strain during their lives, so then why do some participate in delinquent behavior while others do not? Agnew (1992) proposes four factors that predisposed juveniles to delinquency.

- They reach the limit of their known coping strategies, so their reaction is anger and frustration.

- They experience chronic strain which lowers the threshold for tolerance of adversity, meaning that juveniles are unable to deal with increasing levels of strain, acting out even when small events happen in their lives.

- The chronic strain is cumulative, building their anger into hostility and avoidance.

- As things get more difficult for them, they become prone to fits of anger that focus on those they perceive are the cause of their injustices.

Delinquency is then the natural consequence of the strain in their lives.

4.3.6 Status Frustration Theory

In his book The Culture of the Gang, Albert Cohen (1955) proposed status frustration theory, which argues that four factors—social class, school performance, status frustration, and reaction formation (coping methods)—contribute to the development of delinquency in juveniles. His theory assumes that crime is a consequence of the creation of youth subcultures in which deviant values and moral concepts dominate.

Cohen contended that middle-class goals serve as a measuring rod for societal success. When we think about achievement for adolescents, how is it measured? Through SAT scores? Extra-curricular activities? GPA? Does the measure of achievement look at the resources each child has been given? For instance, what if a student’s SAT score looked differently if they came from a failing school compared with scores from students who attended a well-resourced school? Are SAT scores viewed differently if a child was able to pay to take a prep class compared to one who wasn’t able to afford one? In Cohen’s view, this is just part of the creation of the middle-class measuring rod where students are set up to fail because they do not have access to the resources other students have. Students without support may not see value in education and end up not pursuing a higher degree because they believe they have already been set up to fail.

Like anomie, strain, and general strain theories, the frustration that is created by not obtaining desired goals can lead to deviance. However, it is important to note, in all of these cases of strain and frustration, the majority of juveniles are not deviant and do conform to the proposed standards of society. However, those who move toward delinquency may be doing so because there is a sort of status they believe can be achieved through delinquency. Whether it be through violence, monetary delinquency, or just drug/alcohol use, these juveniles finally achieve a level of status they couldn’t outside of their delinquent behavior.

An interesting part of the school system is how, if a child misbehaves, the punishment is suspending or expelling them from school. If their grades don’t meet the minimum, then they may be removed from a sports team or other extracurricular activity that could have given them the status they desired and the taking away of their activity could lead to frustration and possible deviant behavior. Cohen’s main points will be continued in the section in this chapter on “Subculture Theories.”

4.3.7 Licenses and Attributions for Social Structure Theories

“Social Structure Theories” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.2 Photo of Max Weber, 1918 is in the Public domain.

Figure 4.3 Photo of Unemployed men during the Great Depression is in the Public domain.

Figure 4.4 Photo of Chicago 1930s is in the Public domain.