2.1 Chapter Overview and Learning Objectives

2.1.1 Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students will be able to do the following:

- Identify national sources of crime data and official statistics.

- Explain the dark figure of crime and the reason behind the disparity.

- Discuss the challenge with self-reported statistics.

- Analyze the misuse of crime data and statistics.

- Evaluate the challenges with measuring crime.

2.1.2 True Crime Stories: The Myth of the Super-Predator

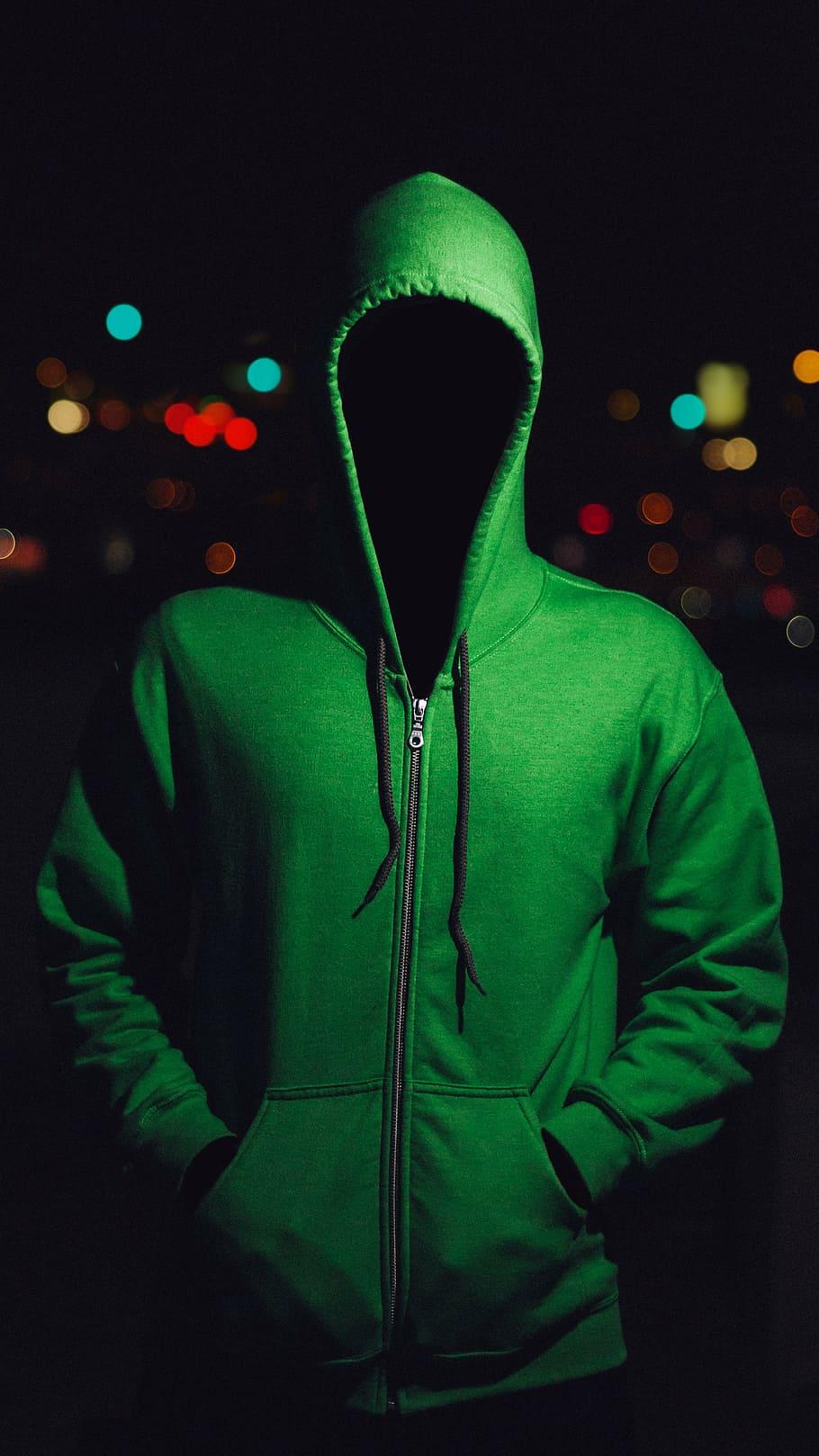

Figure 2.1 Myth of the scary teenager super predator.

Dr. John DiLulio became famous as a criminologist and political scientist, but for a very bad reason. In 1995, he misused data from a different study to predict an impending rise in crime and violence among teenagers, especially African American males. He claimed, “the next ten years will unleash an army of young male predatory street criminals who will make even the leaders of the Bloods and Crips – known as O.G.s, for ‘original gangsters’ – look tame by comparison” (DiLulio, 1995, para. 19). Dr. DiLulio said there was a whole generation of heartless, evil, violent kids living in “moral poverty” who were going to terrorize every community (figure 2.1). In particular, young Black men were going to be coming after white adults.

He called these new scary teens “super-predators” and convinced a trusting public that they should all be terrified of these youth who are marked by “the impulsive violence, the vacant stares and smiles, and the remorseless eyes” (DiLulio, 1995, para. 6). Legislators latched onto his claim because it backed their tough-on-crime rhetoric and allowed them to pass all sorts of new laws punishing juvenile offenders with longer, harsher sentences than ever before – all the way up to sentencing children to life in prison without the possibility of parole. DiLulio (1995) warned,

On the horizon, therefore, are tens of thousands of severely morally impoverished juvenile super-predators. They are perfectly capable of committing the most heinous acts of physical violence for the most trivial reasons (for example, a perception of slight disrespect or the accident of being in their path). They fear neither the stigma of arrest nor the pain of imprisonment. They live by the meanest code of the meanest streets, a code that reinforces rather than restrains their violent, hair-trigger mentality. In prison or out, the things that super-predators get by their criminal behavior – sex, drugs, money – are their own immediate rewards. Nothing else matters to them. So for as long as their youthful energies hold out, they will do what comes “naturally”: murder, rape, rob, assault, burglarize, deal deadly drugs, and get high. (para. 29)

Dr. Dilulio’s claim was busted when crime among juveniles did the opposite of what he predicted. In fact, it went down – a lot. Although, Dr. Dilulio has since come out and publicly said, “Oops,” the impact of his misuse of data has been lasting and incredibly harmful. Accusations over the super-predator myth still come up in political debates and discussions around criminal justice reform, as recently as the 2020 presidential election, making this a legendary example of misusing data in criminology.

This is just one example of how a misinterpretation of crime data can go horribly wrong. This chapter will examine the sources of crime data and the challenges and limitations of measuring crime.