5.3 Crime and Intelligence

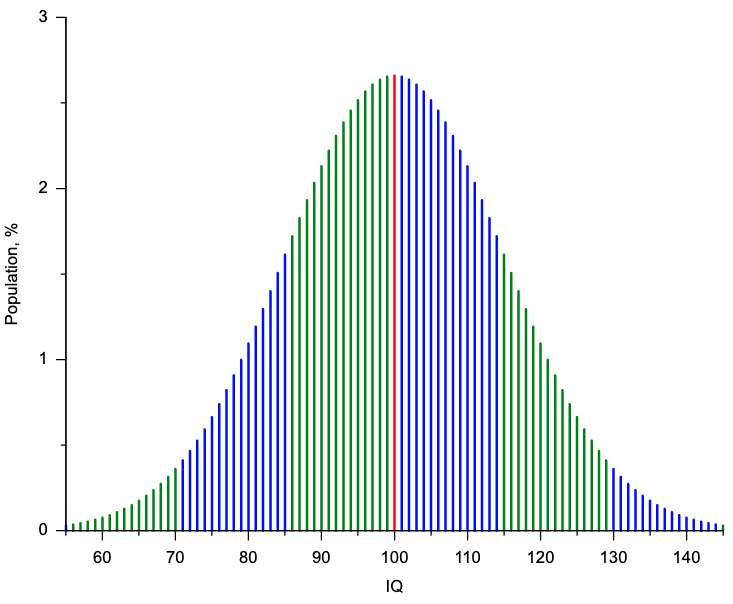

The act of trying to measure intelligence has a disturbing history in the United States and beyond. The first official test (the IQ test or intelligence quotient test) was created by French psychologists Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon in 1904 because they were tasked by the government to figure out which kids needed extra support in school. These good intentions were the basis for a test that placed a specific number on people and ranked them on a scale of intelligence shaped like a bell (you may have heard of the bell curve). The middle of the bell is where most people scored, between 85 and 115. This meant the average intelligence score was determined to be 100 and most people fell within 15 points either higher or lower than that. If someone scored higher than 115, they were considered to be very smart. If someone fell below 85, they were considered the opposite and were eventually labeled undesirable and problematic. Figure 5.2 shows that most (68%) of the population falls in the middle part of the curve, with IQ scores between 85 and 115. Those who fall below the middle range were considered disabled and problematic.

Figure 5.2 Image of bell curve.

This brief video gives a helpful lesson on how something that started with good intentions turned deplorable: https://ed.ted.com/lessons/the-dark-history-of-iq-tests-stefan-c-dombrowski

The reason we look at IQ testing and disabilities in a book on criminology is that these factors were used in deciding whether or not someone was a criminal. This label did not only lead to someone being incarcerated or institutionalized; it also led to their murder. In Virginia, for example, it was legal to forcibly sterilize someone with a low IQ score and in Nazi Germany, it was legal to murder children with scores below average. All of this horror was part of the eugenics movement, in which the criminal justice system and criminologists played a key role. In eugenics, scientists tried to get rid of unfavorable characteristics (low intelligence, criminality, certain physical traits) in favor of others by not allowing for the reproduction of certain devalued people.

5.3.1 The Belief of Feeblemindedness

Figure 5.3 Photo of American psychologist Henry Goddard (1910s).

Henry Goddard (figure 5.3), whom we discussed in Chapter 3 for his outrageous work on the Kallikak family, was a very popular American psychologist, eugenicist, and segregationist. He began his notorious work with the French Binet-Simon IQ test, translated it, and modified it for his own purposes in the United States in 1914. There are a couple of key points to keep in mind as you read about Goddard’s work. One is that his work was read by Adolf Hilter and was used as justification for many of the atrocities committed by Nazis in Germany. The other important point is that Goddard himself later came out to say his findings and recommendations were wrong. Unfortunately, it was too little too late for millions of people.

Goddard advocated colonizing (isolating, incarcerating, or institutionalizing) and sterilizing people he deemed to be “mental defectives.” He provided “research” to support his eugenic beliefs using his updated IQ test. In 1912, he published the study titled The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness that was discussed in Chapter 3. He later admitted his study was deeply flawed, but this was after the results had already influenced future research and even policy. Causing further harm, Goddard, having spent time with youth offenders, claimed that at least half of criminals are mentally defective. In this manner, he created the supposed link between intelligence and crime.

This claim was challenged in 1926 by criminologist Carl Murchison, who maintained that intelligence was not a factor in the causation of crime. Then in 1929, American psychiatrist M.H. Erickson conducted a larger study and discovered a link between IQ and crime, but his research showed that some crimes require a greater IQ than others. What made Erickson’s study different was that he believed that the link between IQ and crime was indirect and that intelligence did not appear to be a causal factor in producing criminals in society.

Then, in 1931, sociologist Edwin Sutherland published a study that contradicted the possible connection between IQ and crime. Sutherland compared the IQ scores of adult offenders to those of army draftees and the two groups had nearly identical IQ levels. The army draftees represented the general population which is something the previous studies failed to measure and then compare. Sutherland argued that if the average IQ of the general population was not known, then it would be impossible to claim it has any effect on human behavior. He concluded that intelligence was not a generally important cause of delinquency (Sutherland, 1931). In spite of Sutherland’s research, the debate over the link between IQ and crime continued for the next forty years.

5.3.2 Contemporary IQ-Crime Connection

In 1961, psychologist Arthur Jensen divided intelligence into two different categories: associative learning and conceptual learning. Associative learning is the simple retention of input or the memorization of facts and skills, for example when you study for an exam and memorize facts you know will be on the test. Conceptual learning is the ability to manipulate and transform information input or problem-solving, such as when that same test has open-ended questions that ask you to think critically about a challenge and offer up possible solutions.

Jensen tested children of racial minority groups in the 1960s and reached two conclusions. First, Jensen concluded that 80% of intelligence is genetic and the remaining comes from the environment. This finding looked directly at the “nature versus nurture” debate, with Jensen arguing that nature (genetics) had more influence on intelligence than nurture (the environment in which a child is raised). Second, he claimed that while all races were equal in terms of associative learning, conceptual learning occurred with a significantly higher frequency in White children compared to Black children. This research led Jensen to problematically conclude that Whites were inherently more able to engage in conceptual learning than Blacks.

In 1967, Nobel laureate and physicist William Shockley stated that the difference between African American and European American IQ scores was because of genetics. This raised a question that has been present in society on the connection between race and intelligence, which later led to the believed connection between crime, race, and intelligence. Shockley (1967) stated that genetics might also explain the variable poverty and crime rates in society.

Working off of Jensen’s findings, sociologist Robert Gordon saw a parallel between IQ scores and delinquency rates revealed in juvenile court records and commitment data. Without much supporting data, Gordon argued that a connection existed between IQ and delinquency in both African Americans and Whites (1976). He concluded that the Black-White IQ difference was essential to address when looking at crime in society and was more important than links between IQ and socioeconomic status.

In a review of research literature, sociologists Travis Hirschi and Michael Hindelang found a small but consistent and reliable difference between the IQs of delinquents and the IQs of non-delinquents. In the studies they reviewed, it was concluded that IQ was an important link to delinquency and that it was more closely related to delinquency than to race and social class. In other words, within social classes and racial groups, persons with low IQs were more likely to be delinquent compared to those with higher IQs. Hirschi and Hindelang connected this finding to school experiences, finding those with lower IQs had negative school experiences and low performance making them more likely to commit delinquent acts (Hirschi & Hindelang, 1977).

5.3.3 The Bell Curve and the Question of Race

In 1994, psychologist Richard Hernstein and political scientist Charles Murray published what soon became a controversial book called The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. In the book, they concluded that low IQ was a risk factor for criminal behavior. In particular, they claimed the more experience White males had in the criminal justice system, the lower their IQ. Hernstein and Murray suggested that low intelligence could lead to criminal behavior by being associated with the following experiences:

- lack of success in school and the job market

- lack of foresight and a desire for immediate gains

- unconventionality and insensitivity to pain or social rejection

- failure to understand the moral reasons of law conformity

They argued that it was cognitive disability rather than economic or social disadvantage that created crime. Because of this, they stated policy should focus on cognitive problems instead of social problems such as unemployment and poverty.

Hernstein and Murray’s study received criticism because of their outdated views of intelligence and the claim that it was difficult to increase IQ scores despite contrary evidence. They explained high crime among African Americans in terms of inherited intellectual inferiority. What Hernstein and Murry failed to consider were the alternative criminogenic risk factors that could exist. By portraying offenders as criminals because of cognitive disadvantage, their research justified repressive crime policy that focused primarily on the individual and not the environment.

It is important to note the research and theories making claims about intelligence and race have been determined to be racist and misleading.

5.3.4 Lifestyle Theory

Forensic psychologist Glenn Walters formulated lifestyle theory as a prison psychologist at the U.S. Penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. Lifestyle theory centers on the belief that criminal behavior is a general criminal pattern of life that is characterized by an individual’s irresponsibility, self-indulgence, negative interpersonal relationships, impulsiveness, and the willingness to violate society’s rules (Walters, 2000). Lifestyle theory concentrates on the development of criminal thinking patterns and was designed to help human service professionals change criminal thinking in their clients.

The three concepts of lifestyle theory are conditions, choice, and cognition. The assumption is that a criminal lifestyle is the result of choices, which can be influenced by biological and/or environmental conditions. Walters’s theory emphasized impulsiveness and a low IQ as the most important features guiding choice and behavior. Further, he also described the cognitive styles that people develop as a consequence of their biological and/or environmental conditions as well as the choices they make in response to them. According to the theory, criminals display thinking errors, such as cutoff, where they discount the suffering of the victim, and power orientation, where they view the world in terms of strengths and weaknesses.

Walters asserted that criminality is the result of irrational behavioral patterns that result in faulty thinking patterns which begin from the consequences of choices made early in life. The early behavioral patterns that exist can extend into criminal behavior later in life because of faulty logic and unrealistic rewards.

5.3.5 Personality Theory

German-British psychologist Hans Eysenck created criminal personality theory to explain criminality by mixing behaviorism, biology, and personality. His goal was to explain the links between personality and crime. He suggested that certain inherited characteristics make crime more likely, but he did not believe that crime was an inherited trait.

Eysenck argued that control of behavior was divided into two categories: conditioning and inherited. Conditioning is the category of personality traits and behavioral characteristics people learn and inherited is the category of those that are genetic. He believed that personality depends on four higher-order factors: ability, extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism.

- Ability is the innate intelligence everyone has at birth.

- Extraversion is an individual’s energy levels that are directed outside of themselves that can be manifested as impulsive sociability.

- Neuroticism is a trait associated with depression, anxiety, and other negative psychological states.

- Psychoticism can make the individual appear aggressive, impersonal, impulsive, and lacking empathy for others.

While he claimed ability was important in the understanding of crime, Eysenck believed the other three factors were more critical predictors. Eysenck’s criminal personality theory claimed that there were two personality types that had the greatest tendency for criminal behavior: neurotic extroverts and psychotic extroverts. Neurotic extroverts require high stimulation levels from their environments and their sympathetic nervous systems are quick to respond. Psychotic extroverts are cruel, insensitive to others, and unemotional. Most of Eysenck’s work has since been rejected, but that did not stop his influence on others.

5.3.6 Licenses and Attributions for Crime and Intelligence

“Crime and Intelligence” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.2 Image of IQ bell curve, Alessio Damato, Mikhail Ryazanov, is in the public domain, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 5.3 Photo of American psychologist Henry Goddard (1910s) is in the public domain, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.