5.4 Social Learning and Motivational Theories of Crime

In Chapter 4, we discussed social learning theory from a sociological perspective. In this section, we will examine social learning theory from a psychological perspective. This involves also diving deeper into what motivates a person to behave in a certain way. Crime prevention practices tend to center more on rational thought and the belief that people understand punishment is bad, so they will not complete the act. However, when criminal behavior occurs because the person committing the act thinks of it more in terms of the positive reinforcement they receive from committing the crime based on what they have seen through observation and action during the course of their lives, that goes against the way prevention had been planned.

5.4.1 Social Learning Theory

Canadian-American psychologist Albert Bandura (1974) defined observational learning as the process by which “people convert future consequences into motivations for behavior.” In other words, people learn by watching others and observing the results of their actions. The unique part of Bandura’s theory was that he argued observational learning did not require direct reinforcement. This is because humans are capable of learning vicariously through the experiences of others or even through their own imaginations.

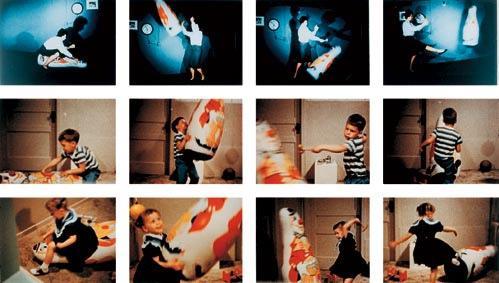

Bandura centered his research on learning aggression. His famous Bobo Doll study involved children who watched an adult attack a plastic clown punching bag named “Bobo,” and then they were rewarded with sweets and drinks for their behavior. Later when the children were in the room with other toys, they chose to attack the doll in a similar fashion as the adults (figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Albert Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment.

Bandura identified four steps in the process of observational learning: attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation. First, the learners observe what is happening (attention) and then remember the actions they observed (retention). Later they reproduce the model’s behaviors (reproduction) and comprehend and appreciate the possible positive reinforcements that account for the modeled behavior (motivation). When the children watched the adults attack Bobo and then get rewarded, they saw and remembered, then repeated the behavior to get the same result.

Bandura saw family members, members of one’s subculture, and models provided by the mass media as primary teachers in observational learning. Even though the research has never produced a direct link between violence on television and any long-term violent behavior in individuals, Bandura was a frequent critic of the violence that appeared on television and in movies. Although research has failed to produce a long-term connection between exposure to violent material and individual violence, there is a clear relationship that exists when looking at the short-term effects among those individuals who were already aggressive (Freedman, 1986).

Bandura was one of the first theorists to see the direct link between observation and aggressive behavior. His belief and that of those who subscribe to his theory is that among individuals who are already aggressive, observing aggression will influence future aggressive behavior. Thus, as a society, we should not be worried about all children when it comes to watching or being exposed to violent behavior in the mass media and popular culture, but rather focus on those children who already have displayed aggressive tendencies.

In today’s society, we may be able to employ Bandura’s theory when it also comes down to verbal violence on social media. The concept of an “internet troll”—an individual who aggressively attacks someone verbally online—is fairly new in our society. This behavior can be modeled and copied by anyone since online anonymity can allow individuals to act in antisocial manners they would never behave in during face-to-face meetings. Whether it is in social media or online gaming, the behavior that is exhibited by others isn’t necessarily their own unique behavior but rather behaviors they have observed and adapted because they see others get away with it.

5.4.2 Operant Conditioning

Figure 5.5 Photo of Ivan Pavlov (1904).

You may have heard of Pavlov’s dogs. It is unusual for someone’s work from the 1900s to have been so popular that it is still commonly referenced today. Nobel Prize winner Ivan Pavlov (figure 5.5) conducted research that resulted in his theory on classical conditioning. In fact, what he learned is still used in dog training today (and in some human training). Pavlov was studying behavior and how to control it (behaviorism). If you have a dog, most likely you have experienced the stimulus-response connection Pavlov found in his research. The belief of classical conditioning is that certain responses are natural and do not require learning. Dogs will salivate when they see food, for example. However, Pavlov discovered that these natural responses can be manipulated. He got dogs to salivate in response to a neutral stimulus (the ringing of a bell), which produced no response until the dog learned to associate it with food. In other words, the bell is rung, the dog is given food and this is repeated. After time, when the bell is rung the dog associates a ringing bell with food so they start to salivate even though no food is present (Figure 5.6).

Pavlov’s operant conditioning led to further research on behavioral conditioning involving humans. In particular, psychologist B.F. Skinner challenged Pavlov’s findings with his theory of operant conditioning. Skinner took the basics of Pavlov’s experiment of connecting a neutral stimulus (the bell) to positive reinforcement (the food). He expanded to look at both good and bad stimuli and also good and bad reinforcements figure 5.7).

Pavlov found this chain of events:

Figure 5.6 Bell rings → dog salivates → dog gets food.

Skinner looked specifically at a chain of events that involved simply:

Figure 5.7 Behavior → consequence.

However, there are different types of consequences and those can make the behavior more or less likely to occur.

Let’s first consider what could make a behavior more likely to occur. The consequence for the behavior could be either giving something (positive) or taking something away (negative). For example, a parent could give a child an allowance in exchange for them completing their chores (positive). Conversely, the child could be required to do their chores if they do not want to get grounded (negative). Either way, the chores are more likely to get done because of the presence of positive or negative reinforcements. A reinforcement is a stimulus that increases the probability of a given behavior, such as being paid for correctly performing a job.

The other layer to this scenario that Skinner proposed is that consequences could make behaviors less likely to happen. In this case, the consequence is still giving (positive) or taking something away (negative), but this time what is being given or taken is more of a punishment than a reinforcement. For example, if a child stays out past curfew and their parent grounds them when they get home, they are less likely to stay out past curfew again. In this case, a punishment is given, so it is considered a positive punishment. The consequence could be that a child stays out past curfew so their cell phone is taken away. Since something is being taken away that makes them less likely to stay out past curfew again, this is called a negative punishment.

Operant conditioning involves the repeated presentation or removal of a stimulus (consequence) following a behavior to increase or decrease the probability of the behavior (Skinner, 1974). Skinner believed different results would occur through the status of the stimulus (whether it was there or not) as well as whether or not the behavior was punished (bad) or reinforced (good). The table in figure 5.8 shows a matrix of these different options.

| Consequence | Reinforcement | Punishment |

|---|---|---|

| Giving something | Positive Reinforcement

(getting a reward) |

Positive Punishment

(getting something bad) |

| Taking something away | Negative Reinforcement

(taking away something bad, avoiding bad) |

Negative Punishment

(removal of something good) |

Figure 5.8 Matrix of behavior and consequence options in operant conditioning.

Studies have shown that behavioral conditioning is rarely this straightforward and can easily backfire. For example, research has shown that spanking can increase aggressive behavior and that the more you spank a child the more likely they are to defy you (Gershoff et al., 2016). Antisocial behavior and aggression have been linked to excessive use of positive punishment while also this type of punishment may contribute to cognitive and mental health problems. It can teach avoidance behavior and for many create a goal of simply “not getting punished” but not have a replacement behavior available.

In summary, positive and negative punishment is used to discourage inappropriate behaviors while positive and negative reinforcement is used to encourage good behaviors. Some students will study for a big exam not only to avoid a poor grade but also to avoid any form of punishment while maybe getting some reinforcement. The overall key is to replace unwanted behaviors with more acceptable behaviors, which is not always a straightforward process.

5.4.3 The Hierarchy of Needs

On a daily basis, what do you need? Think about how some of your needs may distract you from realizing other needs. For example, have you ever been studying for a big exam and forgotten to eat? Have you prioritized your own education or professional attainment over friendships and family? However, if you are worried about your family then possibly that preoccupation will take over your educational goals. In our lives, immediate needs create immediate action. This is the reason why, when personal issues overtake one’s life, other needs suffer.

American psychologist Abraham Maslow looked at our needs in connection with what motivates our behavior. He published a paper in 1943 titled “A Theory of Human Motivation” where he introduced the hierarchy of needs table that is presented in figure 5.9.

Figure 5.9 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Maslow believed that humans are motivated by goal accomplishment and that one’s needs are mentally prioritized in order of importance. However, the hierarchy is not designed to be followed one after another, meaning our focus does not move directly from food to security to friends. Rather, simply put, a person’s action focuses on satisfying their lower-priority needs before reaching the higher-priority needs.

Physiological needs must be satisfied first. We need food, clothing, shelter, and sleep. These are basic needs and why individuals who do not have these needs met can require social services to help them meet these basic needs of survival. For example, people experiencing homelessness do not have a basic need met of shelter and often food and water, which affects their motivations and behaviors until those needs are met.

Safety needs are usually environmental. These will include the environment you are currently in whether it be home, school, or any other location. If there are problems at home, one may have issues paying attention to their education or work because their safety needs have not been met. These home issues could be discord in the house, addiction, no parental structure, or even that the area they live in is dangerous with possibly the noise of police cars and helicopters keeping them up at night (thus interrupting their physiological need of rest as well). Structure and predictability are important when acquiring safety. Routines are important and that was one of the reasons why the COVID-19 pandemic was so difficult for many people because we all were forced to discover new routines.

Love and a sense of belonging apply to family and friend relationships. This is sometimes difficult when you move to a new city or school and away from family without having friends yet. However, joining clubs, volunteering, or going to group activities are great ways to create a new community. Research has shown that we need face-to-face interactions to accomplish a sense of love and belonging. One of the biggest issues faced by individuals in prison is not the violence that could be experienced in prison but rather the loss of freedom and connection to family.

Self-esteem centers on respect for others, confidence, respect from others, and accomplishment. Most people are critical of themselves because of the evaluation of their own accomplishments and their potential. Self-esteem can be found in our need to succeed but it also can be fostered by being appreciated or acknowledged by others. When an individual’s self-esteem needs have been met then a person will feel capable and worthy instead of incompetent and unimportant.

The needs that have been discussed so far can be viewed as deprivation needs. Basically, if these needs are not met then the individual will not be motivated to focus on the highest needs in the pyramid of self-actualization. This is a need that focuses on the ability of an individual to realize their own potential. The focus of this need is self-improvement and Maslow suggests that very few individuals ever attain this level. These are individuals who understand realistic goals with regard to their ability and their own path in life. In other words, Maslow claims we are rarely actually our ideal selves. To achieve this highest level, individuals go to therapy, live in the present, and understand what they need to gain a better sense of fulfillment. Maslow would see society’s addiction to social media and technology as a barrier to achieving self-actualization because it takes us out of the present and makes it impossible to be satisfied and mindful in the moment.

How is the hierarchy of needs part of the study of crime? We can look at any undesirable behavior, including crime, as a need that is not being met. Someone has found an alternative route to meet a need that is not being met in a prosocial manner. For example, if someone does not have consistent reliable access to food, they may steal some. This is a basic need that must be met. If someone does not have safe, reliable housing, they may end up living in a homeless camp. Figure 5.10 addresses the issue of housing and whether or not illegal homeless camps actually generate crime.

In short, to decrease criminal behavior it is important for basic individual needs to be met. This belief has been difficult in some areas because it is seen as a “give out” or people being “freeloaders” but in reality making sure community members have their basic needs met can actually be a strong way to decrease crime in the given community. For example, low-income affordable housing and legal homeless camps and pods can help people obtain those basic needs and be able to move on to meet other important needs in their lives in a legal, prosocial manner.

5.4.4 Activity: Do Homeless Camps Generate Crime?

Figure 5.10 Homeless encampment along city street in Portland, Oregon (2020).

Do homeless camps generate crime? The answer may not be as simple as some might think.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some cities’ tolerance policies let homeless camps enter more visible areas. Subsequently, mayors of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland have all promised to crack down on the camps. But the question is why? Is it just because they are now more visible? The stated concern is an increase in criminal behavior, but are the camps actually generating crime?

On average, just the increase in the number of temporary structures in an area is not associated with an increase in property crime. Even in areas where homeless camps have grown in size, there is still no direct link to an increase in property crime. However, camps are filled with individuals who cannot meet their basic needs. When people are without basic needs, they can turn to drugs to alleviate the discomfort, which can make them addicted and in need of money to support their addiction. This can increase property crime in the area.

If the basic needs are not being met among the population of people experiencing homelessness and that can be linked to crime, what should be done to lower crime or the potential for crime in these areas?

5.4.5 Licenses and Attributions for Social Learning and Motivational Theories of Crime

“Social Learning and Motivational Theories of Crime” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.4 Albert Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment by Creative Commons Attribution, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5.5 Photo by unknown photographer is in the Public Domain, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 5.6 Bell photo by rhoda alex on Unsplash; Dog salivating photo by Mpho Mojapelo on Unsplash; Dog food photo by Mathew Coulton on Unsplash

Figure 5.7 Behavior → consequence

Figure 5.8 Matrix of behavior and consequence options in operant conditioning by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.9 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs by Chiquo, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5.10 Homeless encampment along city street in Portland, Oregon (2020) by Creative Commons Attribution, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.