5.5 Nature versus Nurture: Are We Born Bad?

Crime policy is based on the common belief that humans have free will and “choose” to break the laws; and because of this free will, they should be punished accordingly. But, what if we are born with a propensity to offend? What policy could be created for offenders who were born criminals?

5.5.1 Psychodynamic Theory

Figure 5.11 Sigmund Freud (1921).

Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (figure 5.11) developed psychodynamic theory (which is technically a collection of theories) and psychoanalysis (the therapeutic application of the theories) to explain the source of human behavior. Psychodynamic theory is formed around the following basic assumptions:

- Unconscious motives drive our feelings and behavior.

- Our feelings and behaviors as adults are rooted in our childhood experiences.

- We have no control over our feelings and behaviors since they are all caused by our unconscious that we cannot see.

- Personality is made up of the id (primitive and instinctive), ego (decision-making), and superego (learned values and morals).

A classic example of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory is the Freudian slip or slip of the tongue. According to Freud, that is a revelation from our unconscious and should be believed.

Psychoanalysis applies psychodynamic theory in therapy by examining one’s childhood and trying to better understand your unconscious. Freud believed the unconscious was able to alter one’s conscious values and emotions without the individual being aware of this control. According to Freud, individuals are not aware of what determines their behavior and this is in contrast with the concept of “free will” that was part of the classical criminological theories discussed in Chapter 3.

According to Freud, the unconscious is where unpleasant memories and explosive emotions exist and these both are accumulated as repressed memories and emotions. In other words, what has happened to us in the past can guide our behavior even if we aren’t aware of the connection. We may also be willing to use illegitimate means to get what we want, much like in Merton’s strain theory covered in Chapter 4. According to Freud, in order to help someone change their behavior, it is essential to access and understand their repressed memories, which is again where psychoanalysis comes in.

5.5.2 The Psychopath Test

Are you a psychopath? Well, there is a test you can take to determine if you are. Do not worry if you are because that could just mean that you would become a good CEO of a company. Research has shown that CEOs tend to score high on the psychopath test (Wisniewski, Yekini, & Omar, 2017).

Psychopathy has connections to the study of crime that go back more than 100 years. Many people think of serial killers and people who commit heinous crimes when they think of psychopathy, although we now know it is also common in people who are especially successful in business. Someone who is a psychopath does not have feelings of remorse. Psychopathy is a personality disorder characterized by narcissism and manipulation. Psychopaths may be cold-blooded and violent, but they also know how to use charm to attain their goals.

Early researchers saw psychopathic behavior as moral insanity. The term psychopathic was first used in 1894 by German psychiatrist Julias Ludwig August Koch who studied personality disorders. He viewed people who had emotional and moral aberrations derived from congenital factors as suffering from psychopathic inferiority. Research on psychopathy has continued over the years and has seen several iterations. German Psychiatrist Emile Kraepelin expanded upon Koch’s research in 1904 and created categories of psychopathic personality while also bringing back a moral component to psychopaths. His categories included born criminals, pathological liars, querulous persons (someone who always feels wronged), and persons driven by basic compulsion (such as addicts).

Another German psychiatrist Kurt Schneider continued the work on psychopathy in 1923. He argued there are many types of abnormal personalities that are not harmful. The important distinction, according to Schneider, is that psychopathic personalities suffer from their abnormal personality and cause suffering to others because of it. He identified ten types of psychopathic personalities such as fanatics, emotionally unstable, explosive, insecure, attention-seeking, affectionless, and more. Schneider’s 10 types of psychopaths are the foundation for the later developments over decades of studying the human mind and the connection between what we think and how we act.

Contemporary classifications of psychopaths create a more general vision of psychopathic behavior. Psychopathy in the official psychiatry diagnosis manual (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition; DSM-V) is associated predominantly with boldness, meanness, and disinhibition. The general notion of someone who is a psychopath is one who is charming and makes a good first impression, but actually has a complete lack of empathy and will demonstrate aggression and behaviors that are harmful to others.

In 2011, John Ronson wrote the book The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry in which he explored the idea that psychopaths may not only be criminals but leaders of corporations and politicians in our society. Ronson brings up a very interesting question when looking at behavior in our society: “what is normal behavior?” The CEO of a company who fires a group of workers right before a holiday may be just doing their job and be seen as a strong leader, but does this CEO feel any emotion for changing these workers’ lives? Any for ruining their holiday plans? If not, then could this CEO be a psychopath? This type of behavior occurring in a normalized setting of ruthless behavior does not change the definition of the behavior itself, but rather shows how society views the individual.

5.5.3 Activity: A Forensic Psychologist Test for Psychopathology

Forensic psychologists work within the legal system to translate medical psychological terminology into legal language. They evaluate the current state of the individual and provide treatment and sentencing recommendations. The forensic psychologist will conduct psychological assessments of the individual which include tools such as tests, interviews, behavioral observations, and case studies. These tests can help in understanding the psychological and mental health status of the individual and focus on anything from depression to psychopathy.

Psychopathy can be tested through Forensic Assessment Instruments (FAIs), Clinical Assessment Instruments (CAIs), and The Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) which is the most frequently used tool in violence risk assessment, civil commitments, and insanity evaluations.

Vilijoen et al. (2010) surveyed 199 forensic clinicians about the practices they used in assessing violence risk and found that the use of risk assessment and psychopathy was common. Even though the psychopathy measures were used more with respect to adults, the researchers found that the majority of clinicians (79%) used the measure with juveniles at least once. The issue in this situation is the labeling of juveniles as psychopaths and the long-term effects that would have on their lives. If a juvenile is labeled as a psychopath then this could affect their length of detention and if they are in the adult system then their chance of early release becomes less likely with a label of “psychopath.”

If a person is labeled as a psychopath then can they be helped through therapy or are they simply labeled a psychopath for the rest of their lives?

5.5.4 The Lucifer Effect

For centuries, researchers have been trying to understand how people could commit deplorable acts and why they would do so. After World War II, social psychologists tried to discover why such a horrible event as mass genocide happened and how so many people chose to participate. Psychologist Solomon Asch conducted a study on conformity in the 1950s. His study focused on a “vision test” where a group of students was asked to look at three lines and decide which line matched the length of the reference line. What he was really studying is whether participants would change their answers to match (conform) with others in the group. Asch found that 75% of the participants conformed at least once, and 5% conformed every time. Asch’s study showed how conformity is over-trained in our educational system. Think back to elementary school and how conformity was rewarded. We are taught to conform and, as a result, going against a group is difficult for most.

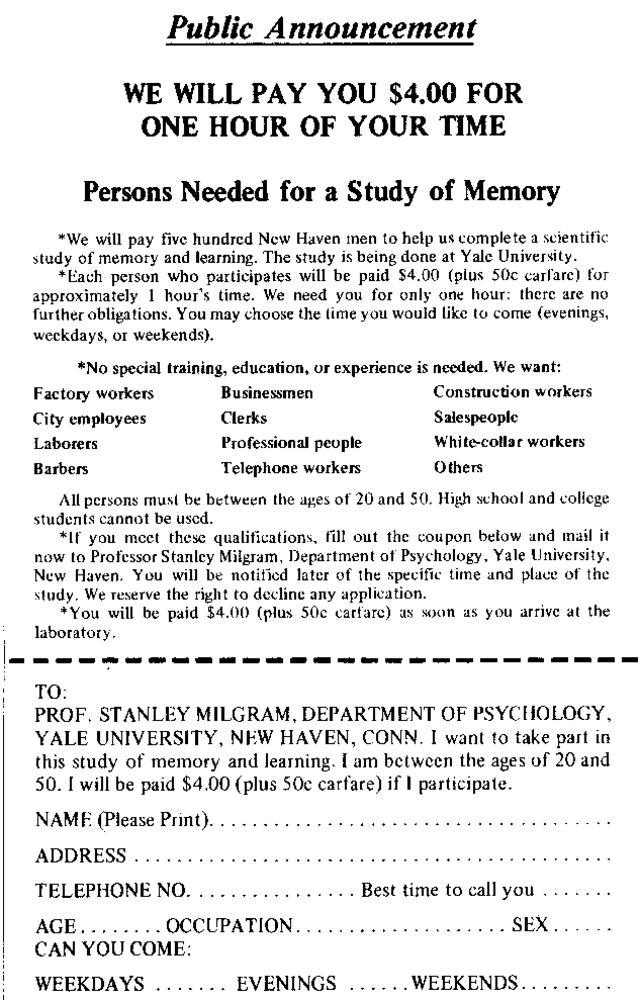

Despite these findings, critics did not think that Asch’s study got at the core of Nazi Germany’s genocide since it was only looking at lines and the decision was not actually about life or death. These critics were challenged by Stanley Milgram’s experiment on obedience (Figure 5.12). By far the most famous conformity research, Milgram began his experiments in 1961 and tried to answer the question of whether or not many of the Nazis were just following orders and being obedient.

Figure 5.12 Advertisement for the recruiting of the Milgram experiment subjects (1961).

The experiment setup was simple. There was a teacher and a learner. Unknown to the “teacher,” the “learner” was a plant in the study (an actor) and knew what was going on. The teacher would read a list of words and the learner had to recall a particular pair from a list of four possible choices. If the learner missed an answer, the teacher was supposed to give him an electric shock. When the teacher paused not wanting to shock the learner (who previously revealed that he was checked out for heart issues) the facilitator of the experiment would say, “The experiment requires you to continue,” and, “It is absolutely essential that you continue,” and finally, “You have no other choice but to continue.” Even after the learner screamed, 65% of the participants in the teacher roles continued to shock the learner up to the highest level (450 volts) and all of the participants in the teacher roles continued administering shocks up to 300 volts. All the teachers shocked the learner at least once.

In his article “The Perils of Obedience,” Milgram (1974) wrote:

The legal and philosophic aspects of obedience are of enormous import, but they say very little about how most people behave in concrete situations. I set up a simple experiment at Yale University to test how much pain an ordinary citizen would inflict on another person simply because he was ordered to by an experimental scientist. Stark authority was pitted against the subjects’ [participants’] strongest moral imperatives against hurting others, and, with the subjects’ [participants’] ears ringing with the screams of the victims, authority won more often than not. The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any length on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study and the fact most urgently demanding explanation.

The willingness of adults to conform to authority could only make a person wonder how much of their behavior is due to the participant’s belief that it is what they are supposed to do in the situation they are in. Phillip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison experiment showed perfectly how quickly individuals would adapt to a given role based on this basic belief.

In 1971, Phillip Zimbardo conducted the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment in which college student participants were randomly assigned the roles of either “guard” or “prisoner.” In this study, the guards quickly began using their power to brutalize and humiliate the prisoners. The experiment was designed to last two weeks, but because of the trauma experienced by the participants, it was stopped after only six days. What caused these normal college students to commit unspeakable acts? Was that what they believed they were supposed to do in that situation or were they themselves evil?

In his 2007 book The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil, Zimbardo sought to explain why people who live “good” lives suddenly engage in “evil” actions. His belief is that the worst criminal behavior could be because an individual conforms to a specific ideology or narrative that tells them those they are harming are not human, they are “others.” This train of thought can be applied to police shootings, school shootings, and all the “evil” actions that are present in our society.

This is what many claim happened in Buffalo, New York on May 14, 2022, when a White man went into a grocery store and killed ten Black individuals. The shooter was motivated by hate and also the White nationalist concept of “replacement theory” which has been supported by some politicians and certain media outlets in the United States. The question could be asked if the one way to prevent mass shootings and police brutality would be to change the narrative that exists from people being the “enemy” or the “other” to everyone being “human.”

5.5.5 Licenses and Attributions for Nature versus Nurture: Are We Born Bad?

“Nature versus Nurture: Are We Born Bad?” by Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.11 Sigmund Freud (1921) by Max Halberstadt, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5.12 Advertisement for the recruiting of the Milgram experiment subjects (1961) by Olivier Hammam, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.