7.3 Classifying Crimes

When looking at crimes, we have to take a step back to try and look at what happened without the emotions involved. This can be really difficult when someone has been hurt. To keep us from reacting based on hurt, anger, and fear, there must be organization and clarity to guide decisions about punishment. For this reason, all crimes have been classified based on their type and severity. In this way, someone can analyze what happened and make decisions about how to move forward without being swayed by their own or anyone else’s feelings or biases (as much as is humanly possible).

First, crimes are grouped by subject matter. Simply put, if the crime was against someone else directly, it is classified as crimes against the person. However, if the crime was one that harms someone indirectly (like taking or damaging something of theirs), it can be classified as crimes against property. This chapter will focus on crimes against the person and Chapter 8 will focus on crimes against property.

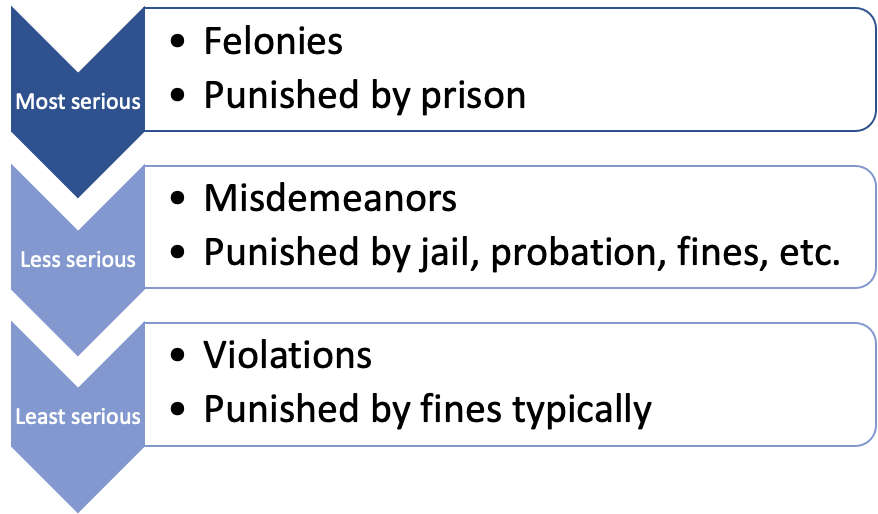

After crimes are grouped by subject matter (person or property), then they are classified by level of severity. This classification directly affects the level of punishment tied to the crime. There are three possible categories in this classification: felonies, misdemeanors, and violations.

A felony is the highest (worst) level of severity of a crime and of the associated punishment. For something to be considered a felony, it is assumed there was a notable amount of intent (it was done on purpose), involves more serious criminal actions or weapons (a lot of harm was done), or targets vulnerable populations (it may have been against a child or another group considered in need of protection). Felonies are the most serious crimes and result in the most severe options for punishment and sentencing. Felonies always include a prison sentence and some may even qualify for the death penalty (execution or capital punishment).

A misdemeanor is considered a less serious crime. For this reason, it is usually punishable by jail time of one year or less. It may also be considered small enough to just be penalized by a fine, or some type of alternative sentencing like probation or community service. More and more, research is showing it is best to keep individuals out of jail if we want them to stop committing crimes, so the focus for these types of offenses is slowly moving toward rehabilitation over simply tossing someone in jail. Some examples include drug courts, mental health courts, and veterans courts that have programs to help address the cause of the crime, rather than just punish the individual for the crime itself.

A violation is the least serious type of crime. These are minor criminal offenses such as jaywalking and traffic tickets. Violations are generally punished with only a fine. There are courts that address these smaller violations (like traffic court), but for the most part they are handled quickly and simply by the offender paying their fine and moving on.

Figure 7.2 shows the classification progression with the severity of punishment for each level.

Figure 7.2 Classification progression with severity of punishment.

There is another layer of classification that happens after something has been determined to be a crime against a person or property, and then categorized as a felony, misdemeanor, or violation. This third level of classification is the level of degree. Degrees start with first for the highest, most severe level and end with fourth for the lowest, least severe level (figure 7.3). To decide the degree, we look at whether there was criminal intent (whether it was done on purpose or was an accident), what exactly was done (the nature of the criminal action), and other considerations like weapons involved or who the victim was (especially if they are considered a special vulnerable or protected group).

Like felonies, within this ranking first-degree crimes are the ones considered the absolute worst and carry the greatest punishment. This classification is decided based on several factors, including:

- Use of a deadly weapon (like a gun, knife, or even the hands of a trained fighter)

- Premeditation (if it was planned in advance)

- Gruesome or particularly violent actions

- Special victims (children, people with disabilities, the elderly)

- Protected victims (such as law enforcement)

- Motive (like hate crimes that will be discussed more in Chapter 10)

The classification of a crime as second-degree means there was something involved that made the crime slightly less bad or more understandable. These are called mitigating factors. An example could be an emotional trigger like provocation or heat of passion, meaning an event happened that upset the person to such a degree that they acted out in a violent manner. There was no premeditation (they did not plan it in advance) and they probably used a weapon of convenience (like a kitchen knife since they did not expect to need a weapon). Consider if a person comes home early from work to surprise their spouse and instead finds them in bed with someone else. It is quite possible they will become outraged and, in the heat of passion, grab a nearby candlestick (weapon of convenience) to bludgeon their spouse to death. They still did it, they knew what they were doing, they knew it was illegal, and they did it on purpose. However, they did not plan to do it in advance. What they did was still very bad and quite illegal, but they are given a tiny bit of a break because of the mitigating factors.

Third-degree crimes are those with more mitigating factors or a little less harm done. An easy example is theft. The person may have stolen something and even planned to do it, but what they stole was of a lower value than things that might fall under first- or second-degree theft.

Finally, the lowest classification is fourth-degree. These are crimes committed by negligence or recklessness and can sometimes be considered “near accidents.” Pure accidents are not criminal. Those are incidents where a terrible consequence is the result of complete misfortune. For example, if a person is struck and killed by a vehicle that malfunctioned through absolutely no fault of the driver, that would be a pure accident. However, if the driver knew of a fault with the vehicle and was aware that the fault could cause the vehicle to malfunction, the death of the person could be classified as a fourth-degree crime. They did not mean to hurt anyone, but they were negligent in not getting their car fixed and reckless by driving it anyway.

Figure 7.3 The progression of degrees of crimes.

7.3.1 Elements of a Crime

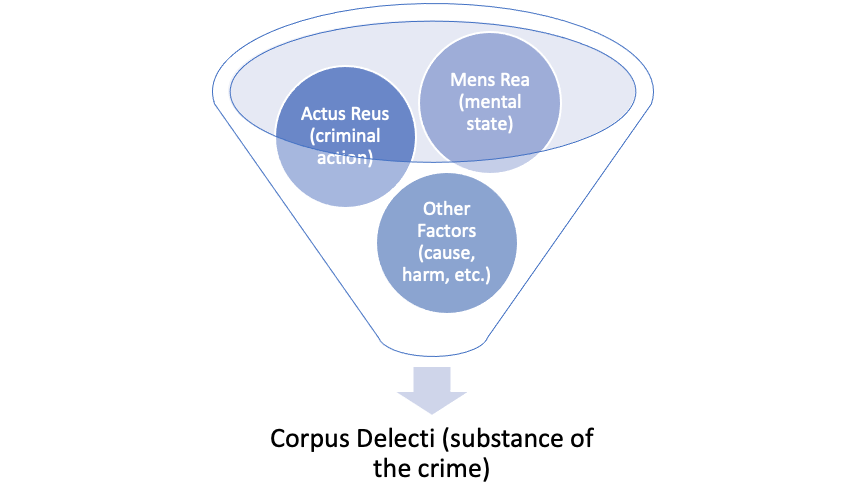

All crimes consist of elements, or criminal behaviors that make an action a crime. With only a few exceptions, every crime has two main elements: criminal intent, also called mens rea and a criminal act, also called actus reus. Mens rea and actus reus must be proven together, with concurrence. Concurrence is the requirement that the mens rea and actus reus exist at the same time and is rarely an issue in a criminal prosecution because the mens rea usually leads to the actus reus. That sounds pretty straightforward, but in reality it usually ends up being more complicated. Let’s look at each piece in more detail to see how they come together.

7.3.1.1 Mens Rea

Mens rea refers to the mental state of the offender when they committed the crime (their criminal intent). It determines the level of accountability, or culpability, we assign to the person charged with the crime. Mental state helps establish the level of awareness a person has when committing a crime. The Model Penal Code (the guide used to define laws) divides criminal intent into four “states of mind”: purposely, knowingly, recklessly, and negligently. These are listed in order of culpability from higher to lower, meaning a person is considered most responsible for a crime they committed purposely and slightly less responsible for a crime they committed knowingly. Think back to the degrees of crime and how these states of mind align with those levels. In mens rea, we are trying to figure out and prove the mental state of the person while they were committing the crime. These four mindsets, states of mind, are widely used as the basis of mens rea in modern criminal law.

As a society, we tend to hold people more accountable when they do criminal actions on purpose and less accountable when they are negligent. In other words, purposely running over a person with your car is seen as more serious than accidentally losing control of your car and running over a person. While the outcome is the same in that someone loses their life, a person would be more accountable for having a purposeful mental state and less accountable for having a negligent mental state. Note that different mental states do not relieve them of accountability altogether, but rather serve as a factor in determining the appropriate crime and degree for prosecution.

As a rule, when higher culpability mental states are paired with more serious criminal acts, the result is more serious charges (felonies, first-degree crimes) and when lower culpability mental states are paired with less serious criminal acts, the result is less serious charges (misdemeanors, fourth-degree crimes). The various combinations of specific mental states with specific criminal actions is what makes each crime unique.

It is important to note, motive and mens rea are different. Motive is about why a person commits a crime. Mens rea is about the mental awareness a person has when committing a crime. Although they are different, motive can be used to help determine mens rea.

7.3.1.2 Actus Reus

As we said, actus reus is the actual criminal act. Actus reus refers to specific actions that have been identified as criminal within a law. Every law details very specific conduct that constitutes a certain crime. Actus reus is thought of in two ways: voluntary action and failure to act.

Voluntary action means that a person committed the criminal action of their own will and self-movement. Failure to act is inaction in a circumstance that leads to great harm, enough to make it criminal. Normally, laws seek to keep a person from doing criminal actions. Failure-to-act laws, however, are designed to address conduct that should have been done, but was not. For example, child neglect makes it a crime to “fail to care for a child.” Failure to act is only criminal in three situations: when there is a law that creates a legal duty to act, when there is a contract that creates a legal duty to act, or when there is a special relationship between the parties that creates a legal duty to act (like a parent to a child).

7.3.1.3 Concurrence

Remember, we said we must have concurrence, meaning mens rea and actus reus must exist at the same time. Concurrence can be complicated by factors like what lead up to the crime, the resulting harm or injury, and other relevant circumstances. However, when the actus reus, mens rea, and other criminal elements align, we have demonstrated the corpus delicti, or the substance of the crime as shown in figure 7.4. Corpus delicti means “body of the crime” but actually refers to the principle that all the elements of the crime have occurred and the substance of the crime has been proven.

Figure 7.4 The components of Corpus Delicti.

7.3.2 Licenses and Attributions for Classifying Crimes

“Classifying Crimes” by Jennifer Moreno is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.2 Classification progression with severity of punishment by Jennifer Moreno is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.3 The progression of degrees of crimes by Jennifer Moreno is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.4 The components of Corpus Delicti by Jennifer Moreno is licensed under CC BY 4.0.