9.5 Organized Crime

The rise in organized crime is an example of unintended consequences of what people thought were good intentions. In the early 1900s, an influential group determined that alcohol was causing too many problems in society and should it be abolished. Eventually, that movement led to the 18th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution (U.S. Const. amend. XVIII). By 1920, it became illegal to conduct production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. With a complete ban (or prohibition) on alcohol, others saw this as an opportunity for personal gain. Illegal production and sale of alcohol, which was called “bootlegging” as well as the sudden creation and growth of “speakeasies” (secret bars) meant big business for those willing to take the risk. This special opportunity is often credited with the prominent rise of organized crime syndicates and the solidification of organized crime in this country.

Organized crime consists of gangs, mobs, mafia, or any sort of criminal syndicates that are an association of individuals who work together to make money through illegal means. They work to gain power, influence, and money usually through criminal activity that includes corruption and violence. There is often a tight-knit family mentality or even blood ties that keep members from turning on one another. The structures and make-up vary, as well as the legal and illegal activities of each group, often with international ties. However, when we talk about organized crime, these are typically groups that operate at a much higher level than smaller street gangs.

Despite the variety across groups, the U.S. Department of Justice has identified the following features as common to all types of organized crime (OCGS, 2021):

- Reliance upon violence, threats of violence, or other acts of intimidation;

- Exploiting political and cultural differences between nations;

- Gaining influence in government, politics, and business through corrupt means;

- Holding economic gain including investment in legitimate business; and

- Insulating leadership from prosecution through hierarchical structure.

The Organized Crime and Gang Section (OCGS) of the Department of Justice is a specialized group of prosecutors charged with developing and implementing strategies to disrupt and dismantle the most significant regional, national, and international organized crime groups and violent gangs (OCGS, 2021).

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Interpol, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the National Security Council, and international agencies around the world all work together to combat organized crime. The main enforcement efforts are directed against international organized crime groups, which pose serious threats to the well-being of Americans and the stability of our economy. International organized crime (IOC) promotes corruption and violence, jeopardizes our border security, and causes untold human misery. IOC undermines the integrity of banking and financial systems, commodities and securities markets, healthcare systems, and internet commerce.

OCGS attorneys prosecute organized crime cases in cooperation with United States Attorney’s offices across the country. These cases involve a broad spectrum of criminal laws, including extortion, murder, bribery, fraud, money laundering, narcotics, and labor racketeering. In addition, OCGS reviews all proposed federal prosecutions under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) law and provides extensive advice to prosecutors about the use of this powerful statute. The RICO Act is a federal law designed to combat organized crime in the United States that was passed in 1970. Interestingly, it was originally designed to address corruption within leadership of labor unions, but was quickly expanded to prosecute criminal organizations of varying types.

The RICO Act is distinct in that it includes conspiracy, which allows the connections among crimes that may appear unrelated. Previously, crimes would have to be prosecuted in a way that allowed them to only be grouped by the person who was carrying them out. RICO changed that in a very significant way. Through RICO, prosecutors can tie together seemingly unconnected activities that have the same goal of furthering the criminal syndicate and bust not only the person carrying out the crime, but the one who ordered them to do so. By bundling these crimes together, RICO allows law enforcement to take down the boss calling the shots, ordering their underlings to actually commit the crimes while they keep their hands clean (Remember that last feature identified by the Justice Department of “insulating leadership from prosecution through hierarchical structure.”). All these crimes can be linked together in a way that demonstrates the existence of a criminal enterprise and prosecutors can go directly to the head of that group. Also, RICO allows for a condition of no further contact with others involved in the same “racketeering” enterprise, making it difficult for members of criminal organizations to continue their work together.

9.5.1 RICO and the Mafia

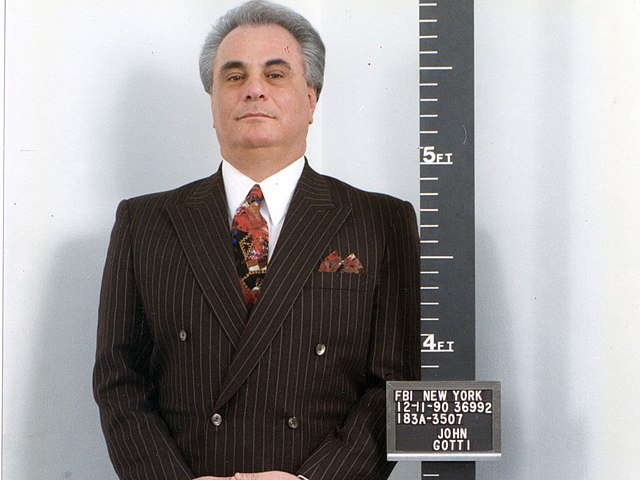

Figure 9.4 FBI Booking photo of John Gotti, head of the Gambino crime family.

In the fifty years that RICO has existed, it has reportedly been a key tool in taking down notorious mob bosses.

In 1977 and 1978, The Cowboy Mafia across Texas, Tennessee, and Florida got busted for importing marijuana on shrimp boats. Twenty-six members were convicted and the boss was brought down under RICO.

In 1979, RICO was used to go after Sonny Barger and the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang. It didn’t quite work, at least not the first time. Prosecutors keep coming after them.

In 1980, the head of the Genovese crime family was taken down by RICO. Then, prosecutors went after the heads of five more Mafia families in New York City and successfully convicted them as well.

In 1984, the Key West Police Department, including Deputy Police Chief Raymond Cassamayor and several high-ranking officers, were convicted using RICO for running a protection racket for cocaine smugglers.

In 1992, John Gotti and Frank Lacascio of the Gambino crime family were convicted under RICO (figure 9.4). Later, in the mid-1990s, the Lucchese crime family faced the same fate.

Then, in 2004, Bonanno crime family boss Joseph Massino was busted by RICO and agreed to cooperate with law enforcement to flip on more of the crime syndicate (ratting on his own family) in order to keep himself off death row.

9.5.2 Mens Rea in Organized Crime

Mens rea for organized crime requires that the offender have specific knowledge and intention to promote and further the goals of the criminal syndicate and recognition that the objectives of the organization are superior to the desires or potential consequences for the individual. In other words, members will do anything for the good of the group, no matter the risk involved. They are 100% devoted, far and above their own individual interests or concerns.

9.5.3 Actus Reus in Organized Crime

Along with the mens rea, organized criminals must commit any criminal action as part of an ongoing criminal enterprise. Commonly, those crimes are financially motivated in nature, like fraud, money laundering, or counterfeiting, but more vicious and dangerous criminal syndicates commonly participate in murder, human trafficking, and drug smuggling.

9.5.4 Types of Organized Crimes

Organized crimes are any crimes that are committed in compounding number and seriousness, specifically performed with the overall goal of furthering the criminal enterprise to exert power, control, and influence.

While individual members of the organized crime unit can be investigated and prosecuted for basic violations of criminal law, the greater aspiration in the fight against organized crime is the prosecution of high-level bosses, the illumination of complex criminal networks, and the dismantling of highly coordinated, dangerously exploitative criminal syndicates.

Organized crime enterprises commit basic crimes at all levels, but they tend to rely on more complex criminal ventures including:

- Drug dealing and trafficking

- Human and migrant smuggling or trafficking

- Exotic wildlife smuggling

- Illegal firearms trafficking

- The sale of stolen goods and artifacts

These crimes provide revenue for organized crime syndicates. While the distribution and sale of illicit items is common, more complex versions of these crimes help increase the power and income of the group. Computer technology has also created a new frontier for organized criminals. Crimes once limited by the physical location of the group can now occur worldwide via the internet, social media platforms, and dark web operations.

Offenses at the organized crime level are generally treated as a felony in most jurisdictions. More specifically, the combined size and complexity of the crimes on a large scale, common to organized criminals, increases the crimes from lower-level offenses to major inter-jurisdictional schemes – especially under RICO.

9.5.5 Licenses and Attributions for Organized Crime

“Organized Crime” by Jennifer Moreno is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.4 FBI Booking photo of John Gotti, head of the Gambino crime family, FBI New York, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.