3.5 Modern Application: How Is It Relevant Now?

So far, we have discussed how pre-classical justice led to the development of criminology. More specifically, we looked at how the classical school of thought and the positivist school of thought came to be. For reference, a portion of the table from Chapter 1 is included in figure 3.11 to help summarize the distinction among these paradigms. However, we have really only focused on the initial iterations of these theories and paradigms. Are these ideas still relevant today? If so, how and to what degree?

| Paradigm | Assumptions |

|---|---|

| Pre-classical criminology | Crime is a result of paranormal forces or demonic possession. This outlook on crime is grounded in religion and superstition. |

| Classical school of criminology | Crime is a result of free will and an individual’s choice to offend. This outlook on crime is grounded in personal choice. It was developed during the Age of Enlightenment. |

| Positivist criminology | Crime is a result of internal or external forces that can be biological, psychological, or sociological. This outlook on crime is grounded in determinism and the scientific method. |

Resurgence of the Classical School

The idea that free will was the cause of crime became unpopular among scholars after the shift to positivism in the late 19th century. Particularly after Darwin (2004) introduced his theory of evolution, scientists and philosophers largely abandoned the classical school assumptions when studying crime. This lasted for about 100 years. However, the foundational idea of deterrence that is central to classical criminology became ingrained in justice systems during this time, especially in France and the United States. Then, in the 1960s, classical school theories experienced a rebirth among criminologists with a resurgence in research on deterrence. Attention to classical school criminology from a new perspective and more modern context is referred to as the neoclassical—neo meaning new—perspective.

Although the classical and neoclassical perspectives share the same basic assumptions—namely, that crime is the result of choice and free-will—there are slight differences. First, the neoclassical approach is more considerate of circumstances that can affect decision-making, such as age or disability. Second, due to a more complex understanding of factors that impact choice, the neoclassical approach is willing to apply different punishments based on mitigating or aggravating circumstances. In other words, a person who steals a car to get away from someone who is abusing them (mitigating) is not viewed as being as guilty as someone who steals a car for fun (aggravating). From a neoclassical perspective, those two people would not deserve the same punishment.

The classical and neoclassical schools have existed at the core of the American criminal justice system’s assumptions and operations. While classical perspectives were abandoned by the academic world for a period of time, researchers finally began to study and test the ideas in the 1960s. Not only did this lead to empirical research on the classic deterrence theory and rational choice theory, but new concepts emerged as well.

Testing Deterrence

Recall that deterrence theory requires punishment to be swift, certain, and severe in order to have a deterrent effect. Initially, researchers testing deterrence theory conducted studies relying on objective measures of apprehension and punishment. Think back to the operational definitions we discussed in Chapter 1, and consider how these scholars tried to define and measure concepts like apprehension (getting caught) and punishment (the actual consequence of getting caught). To do this, they looked at anonymous data of arrests and sentencing to measure the actual certainty and severity of punishment for different crimes.

For example, sociologist Jack Gibbs (1968) compared the number of prison admissions for homicide to cases of reported homicide to determine the certainty of punishment. He also compared the number of prison admissions for homicide to the average length of prison sentences served for homicide to measure the severity of punishment. He then calculated the relationship between the certainty and severity of punishment and compared it to crime rates across the country to see what appeared to be working (or not). He found, as predicted by deterrence theory, that states with higher certainty and severity of punishment had lower crime rates, and states with lower certainty and severity of punishment had higher crime rates. This means deterrence seemed to be working as originally theorized.

Other research using similar methods also found a consistent deterrent effect of the certainty (or risk) of punishment on crime. However, many studies also found that the severity of punishment was directly related to crime rates—that is, states with higher severity of punishment had higher crime rates, whereas states with lower severity of punishment had lower crime rates (Paternoster, 1987). These findings did not support deterrence theory or what the classical school claimed would work to deter crime.

Later research relied on perceptual measures of punishment, or what people thought would happen to them if they were caught for committing a crime. These studies surveyed individuals and asked them about their perceptions of the certainty (and sometimes the severity) of punishment for hypothetical crimes. For example, to measure the certainty of punishment, Saltzman and colleagues (1982) asked participants, “Out of the next 100 people in (city name) who commit ‘crime x,’ how many do you think will be arrested?” Researchers using these types of perceptual measures would then analyze their relationships to self-reported crime (or intentions to offend). Like the earlier research with similar measures, this research also created support for the certainty effect that was claimed in deterrence theory (Nagin, 1998). Also, as was predicted by Beccaria and consistent with the earlier studies, perceived severity of punishment has only a weak relationship to whether or not someone would commit a crime (Paternoster, 1987; Apel & Nagin, 2011).

Over the past few decades, a lot of scholars have tested different claims of deterrence theory and even made changes to the theory as a result of what they learned. For example, Stafford and Warr (1993) looked at the effects of punishment someone experienced themselves (direct) compared to what they saw someone else experience (observed), and argued that deterrence is a learning process based on direct and observed experiences of not only being punished but also getting away with crime.

Research on the deterrent effects of sentences, particularly the death penalty, has produced contradicting results that sometimes make it difficult to draw concrete conclusions. However, taking the literature into consideration as a whole, some aspects of deterrence theory are more effective than others. While certainty of being caught and punished can decrease offending behavior, severity has been shown to have little to no impact on behavior. In fact, some researchers report on what they describe as a brutalization effect, or increased violence and homicide after death penalty sentences are carried out, that runs contrary to a deterrent effect due to punishment severity (Cochran & Chamlin, 2000).

Testing Rational Choice

Like deterrence, Bentham’s rational choice theory has its origins in the classical school of criminology but was largely overlooked until the 1960s when it was revitalized by new research. The main argument of rational choice theory is that people who commit offenses consider the potential costs and benefits of various courses of action before making decisions about whether to commit crimes. Costs include, but are not limited to, formal (legal) and informal (social disapproval) sanctions. Benefits include a variety of potential rewards from criminal behavior, such as money, status, and power.

In considering the rational choice approach, economist Gary Becker (1968) described crime as being like any other economic behavior guided by the consideration of costs and benefits. The rational choice perspective was also elaborated on in greater detail by Cornish and Clarke (1986) in their book The Reasoning Criminal: Rational Choice Perspectives on Offending. They argued in favor of viewing people who commit crimes as being essentially the same as other reasoning individuals who do not commit crimes. In some situations, weighing the pros and cons reveals that the criminal option is the most logical choice.

Additionally, this newer take on rational choice acknowledges that people who commit offenses act with bounded rationality. Bounded rationality is the constraint of both time and relevant information on decision-making. People who commit crimes must make a decision in a timely fashion with the information at hand. They cannot wait forever, nor can they wait for more information before committing a crime. For example, if you were walking down a street and noticed a parked car with an open window, you may contemplate looking in. If you saw something inside, you may then consider stealing it. An entirely rational person may look around to see if there are any witnesses, try to determine if the owner is coming back soon, and so on. Ideally, you may wait until nightfall. However, waiting may cause you to miss your opportunity. Thus, you need to make a quick decision based on the relevant facts available at that time.

The rational choice perspective paints a unique portrait of human nature that depicts individuals as conscious, thinking, reasoning agents who act deliberately, making clear decisions and choices in their lives. It became more popular and influential because of the frequent findings in studies testing deterrence theory. Scholars found that informal sanctions (like negative reactions from family and friends) were more important to people in terms of influencing their intentions to commit crime than formal, legal consequences (Tittle, 1977). In other words, people place greater value on job loss, a tarnished reputation, and harm to their relationships with significant others than on the actual legal consequences of committing crime.

Routine Activity Theory

By the 1980s, technology was progressing at lightning speed, and more people were getting access to what was previously rare, including televisions, computers, and video games. The era was marked by greed and capitalism, making the divide between the “haves and have-nots” even more obvious. Marcus Felson and Lawrence Cohen looked at these changes through their criminologist lenses and saw some key changes to daily life that were affecting criminal behavior. For example, college enrollment was up, more women had joined the workforce and were no longer staying home with their kids, people had portable technology with them like never before, and far more people had cars that allowed them to go further and faster than ever before. All these changes majorly impacted the day-to-day life and routines of Americans.

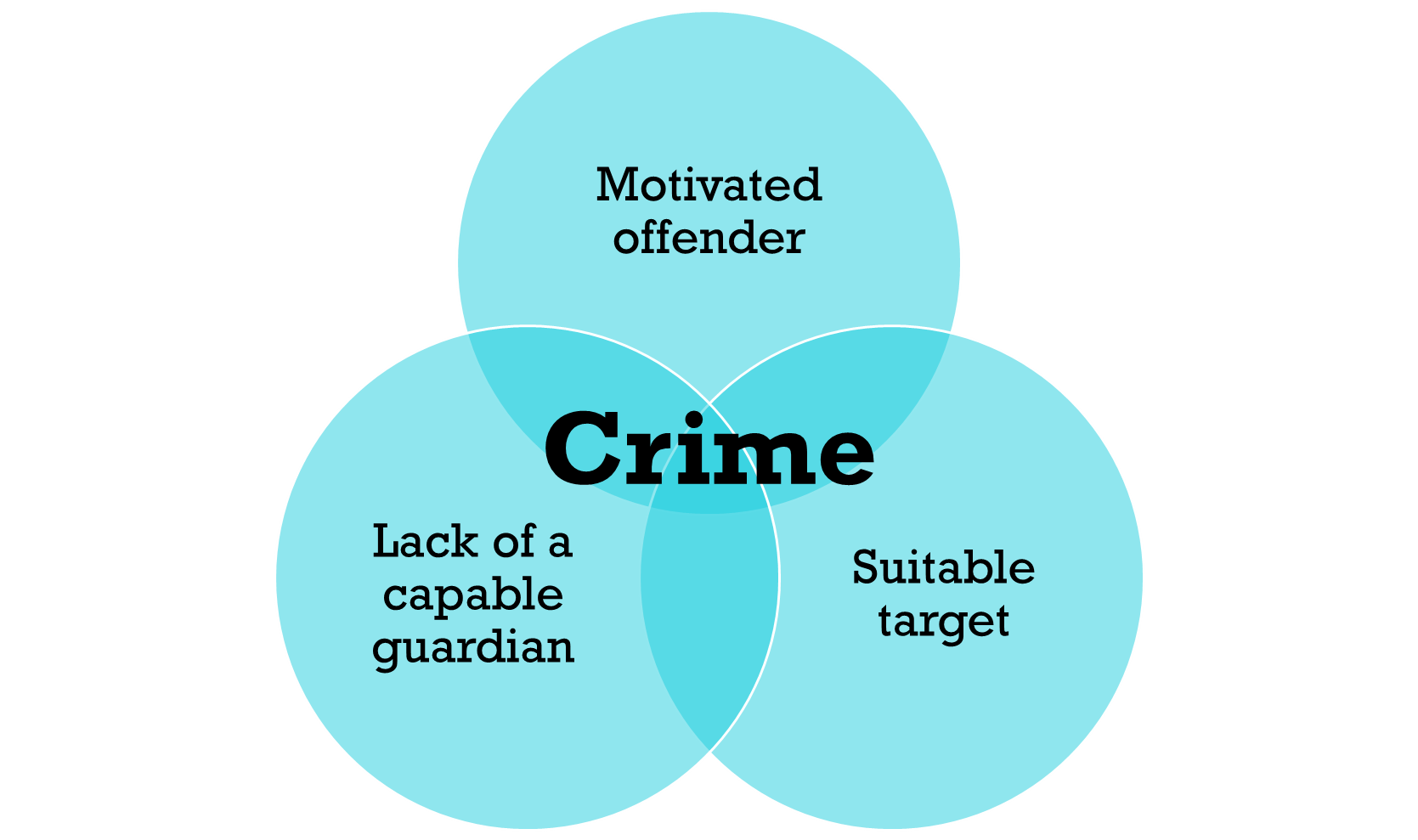

Felson and Cohen (1979) coined the routine activity theory that sees crime as a function of people’s everyday behavior (figure 3.12). They said that for a crime to be committed, three elements must exist: a suitable target, a motivated offender, and the absence of guardianship (Cohen & Felson, 1979). For example, consider the scenario from earlier. Let’s say you walked down a street, looked inside a car that had its windows down, and stole a cell phone that had been left inside. Routine activity theory would explain this as a convergence of a motivated offender (you), a suitable target (the accessible cell phone), and the lack of a capable guardian (no police or witnesses). In other words, the motivated thief is present near an easy target that is not adequately protected.

Routine activity theory looks at our lifestyle and behavioral patterns to determine our risk of either committing a crime or becoming a victim of one. Some researchers criticize this theory for being “victim-blaming” since, instead of focusing solely on the motivated offender, the theory includes the victim and what the victim could have done differently to avoid being victimized. Studies show that some behaviors make people more vulnerable, such as excessive alcohol and drug use or walking in unpopulated areas at certain times. When a motivated offender is around, this theory claims such behaviors can create a suitable target if proper guardianship is not in place. Guardianship can take the form of security cameras, the presence of other people, good lighting, heightened awareness of your surroundings, locked doors, and any other tool at your disposal that may help keep you safe.

Routine activity theory has been used to explain the change in criminal activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the first month of the lockdown, crime fell by 23% and researchers believe that drop was directly related to the population’s mobility. Business closures and stay-at-home orders meant fewer people were outside of their homes. During the pandemic’s restrictive times, home burglaries dropped, but commercial burglaries and car thefts rose. It could be said that the motivated offenders needed to find a suitable target that wasn’t guarded, so cars and businesses became the focus. Residential burglaries decreased by 24%, while nonresidential burglaries rose by 38%. Since people weren’t leaving their homes, cars stayed parked for a longer period of time, and in some cities, the rate of car thefts doubled during the pandemic.

Impact on Policy

Deterrence theory has had a significant impact on the administration of justice and criminal justice policy in the United States. Deterrence theory was especially popular among politicians and others during the “tough on crime” era of the 1980s and 1990s and is still used in political campaigns today. During the 1980s and 1990s, voters, legislators, and policymakers across the United States rejected the idea of rehabilitating individuals who had committed crimes. Instead, they began advocating for tougher sentences, longer prison terms, and other harsh penalties (like mandatory minimum sentences), with deterrence as their justification. Programs like “Scared Straight” were designed and implemented to scare “delinquent” youth by confronting them with the harsh extremes of imprisonment. Other correctional programs, such as boot camps, were designed to be as mentally and physically unpleasant as possible.

Unfortunately, the record on such deterrence-oriented programs is quite clear: increasing the harshness of punishment is an ineffective and inefficient approach to deter crime (Apel & Nagin, 2011). In other words, it does not work. Specifically, the evidence shows that, on average, incarceration has either no effect or actually increases crime, casting significant doubt on specific deterrence (Nagin et al., 2009). Also, boot camps, Scared Straight, and other juvenile “awareness” programs have been shown to be ineffective at best and criminogenic (crime-generating) at worst (Petrosino et al., 2003).

Learn More: Does D.A.R.E. Deter Drug Use?

The popular anti-drug D.A.R.E. program of the 1980s and 1990s has been one of the most widely used programs aimed at deterring drug use among youth (figure 3.13). D.A.R.E. was a school-based program aimed at preventing drug use among elementary school-aged children through a curriculum that was taught by police officers. Rigorous evaluations of the program show that it was ineffective and sometimes actually increased drug use in some youth. The cost of this program was roughly $1.3 billion dollars a year (about $173 to $268 per student per year) to implement nationwide (once all related expenses, such as police officer training and services, materials and supplies, school resources, and so on were factored in).

A newer version of this program, keepin’ it REAL (kiR), emerged in the first decade of the 2000s and takes a broader approach to decision-making beyond just substance use. Some studies have shown potential benefits from this program, including deterring alcohol use and vaping (Hansen et al., 2023). However, more research will be needed to determine if the newer program can achieve long-term deterrence for youth.

If you have experience with D.A.R.E. or keepin’ it REAL, reflect on what you think did or did not work.

Although some deterrence programs have failed, our understanding of deterrence has also produced some effective methods for reducing crime. Think of cameras, patrol cars, and other tools that make people think they are more likely to be caught speeding and get a ticket. As you have probably experienced, the presence of a camera or patrol car makes people slow down (at least until they are out of sight of the police car). Some research has shown that the certainty of apprehension has a stronger, larger, and more consistent impact on decreasing crime than the severity of punishment (Paternoster, 1987). With this in mind, cities will use police crackdowns and other strategies that increase the certainty of apprehension to reduce crime. Probation programs that rely on frequent drug testing and swift, certain, and fair sanctions for people who violate the conditions of their probation by using illicit drugs or alcohol, such as Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation with Enforcement, have been shown to reduce criminal reoffending (Kleiman, 2009).

In general, research has shown that increasing the actual or perceived risk of apprehension or punishment has at least a short-term deterrent effect on crime. Research is less clear about the long-term effect of deterrence on crime.

Although it shares the same assumptions about human nature as deterrence theory, the rational choice perspective offers a broader framework for understanding criminal decision-making because it considers a wider array of influences than just criminal justice apprehension and punishment. This has been particularly useful in the development of practical solutions to address crime. Specifically, situational crime prevention techniques, such as the use of lighting and security cameras, have been used widely in the public and private sectors to increase the risk of apprehension. Studies of these tools consistently show that crime decreases when the appearance of a higher likelihood of getting caught increases.

Activity: Routine Activity Theory in Modern America

Let’s think about how routine activity theory might operate in our current society (figure 3.14). First, take a look around your own local community. Identify an area—a street, public space, neighborhood, parking garage, or somewhere else—where a motivated offender might be likely to commit a crime. In two to three sentences, explain why this area is conducive to crime according to routine activity theory. Take a photo of this space to share with your classmates (optional). Then, still using routine activity theory, discuss how we might be able to decrease the risk of crime occurring in that location. Do you think that routine activity theory helps prevent crime in modern America?

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Modern Application: How Is It Relevant Now?

Open Content, Original

“Modern Application: How Is It Relevant Now?” by Jessica René Peterson and Taryn VanderPyl is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.11. “Table of Paradigms and Assumptions” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.12. “Diagram of Routine Activity Theory” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Modern Application: How is it Relevant Now? Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Testing Rational Choice” is adapted from”Neoclassical“, Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Brian Fedorek, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson and Taryn VanderPyl, which include substantially expanding and rewriting, are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Learn More: Does D.A.R.E. Deter Drug Use?” is adapted from “The Stages of Policy Development,” Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, which include adding some updated information, are licensed under CC BY 4.0,

“Bounded rationality” definition by Brian Fedorek from SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 3.13. “Bolden D.A.R.E. graduates say no to drugs 151216-M-SK244-003” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 3.14. “Cocoa Beach at Lori Wilson Park – Flickr – Rusty Clark (5)” by Rusty Clark is licensed under CC BY 2.0.