8.3 Feminist Criminology

A central definition of feminism can be challenging, because as figure 8.6 illustrates, there are many kinds of feminism, each with its own unique focus. However, there are features common to every type of feminism that we can use to establish a solid foundation when exploring feminist criminology. Primarily, feminism argues that women suffer discrimination because they belong to a particular sex category (female) or gender (woman), and that women’s needs are denied or ignored because of their sex. Feminism centers the notion of patriarchy in understandings of inequality, and largely argues that major changes are required to various social structures and institutions to establish gender equality. The common root of all feminisms is the drive toward equity and justice.

| Type of feminism | Perspective on criminology |

|---|---|

| Liberal feminism: feminism that focuses on achieving gender equality in society | Liberal feminism assumes the differences between men and women in offending behavior is due to lack of opportunities for women in education and employment. |

| Radical feminism: feminism that emphasizes structural patriarchy in which men dominate every aspect of society, including politics, family structure, and the economy | Radical feminism assumes the criminal justice system is a tool used by men to control women. |

| Marxist feminism: feminism that emphasizes men’s ownership and control of the means of economic production and sees the capitalist system as women’s main oppressor | Marxist feminism assumes that unequal economic access led to women being disproportionately involved in property crime and sex work. |

| Socialist feminism: feminism that combines radical and Marxist theories/feminism | Social feminism assumes that differences in power and class account for gendered differences in offending behavior, especially pertaining to violence. |

| Postmodern feminism: feminism that focuses on the construction of knowledge and rejects the idea of a “universal female” | Postmodern feminism assumes that the diversity of women needs to be highlighted when one considers how gender, crime, and deviance intersect to inform reality. |

| Intersectional feminism: feminism that critiques the failure of other perspectives to consider one’s position in society and multitude of identities when understanding how life and inequality are experienced | Intersectional feminism assumes that inequalities intersect to influence women’s pathways to offending and/or risk of victimization. |

Feminist activism has proceeded in four “waves.” The first wave of feminism began in the late 1800s and early 1900s with the suffragette movement and advocacy for women’s right to vote. The second wave of feminism started in the 1960s and called for gender equality and attention to a wide variety of issues directly and disproportionately affecting women, including domestic violence and intimate partner violence [IPV], employment discrimination, and reproductive rights. Beginning in the mid-1990s, the third wave focused on diverse and varied experiences of discrimination and sexism, including the ways in which aspects such as race, class, income, and education impacted such experiences. It is in the third wave that we see the concept of intersectionality come forward as a way to understand these differences.

The fourth wave, our current wave, began around 2010 and is characterized by activism using online tools, such as social media. For example, the #MeToo movement is a significant part of the fourth wave. The fourth wave is arguably a more inclusive feminism—a feminism that is sex-positive, body-positive, trans-inclusive, and has its foundations in “the queering of gender and sexuality-based binaries” (Sollee, 2015). This wave has been defined by “‘call out’ culture, in which sexism or misogyny can be ‘called out’ and challenged” (Munro, 2013).

Feminist criminology was born in the second wave of feminism. Feminist activism during this time brought attention to the inequalities facing women, including their victimization, as well as the challenges female offenders faced within the criminal justice system. The breadth and extent of domestic violence, specifically men’s violence against women within intimate relationships, was demonstrated by the need for domestic violence shelters and the voices of women trying to escape violence. Conversations at the national level led to the establishment of shelters funded by the government as well as private donors.

At the same time, the historic and systemic trauma of women involved in the criminal justice system as people who had committed offenses was being recognized. Attention began to be paid to their histories of abuse, poverty, and houselessness and to the other systemic discrimination they faced. Historically, women who have been regarded as criminally deviant have often been seen as being doubly deviant. Not only have they broken the law, but they have also broken gender norms. In contrast, men’s criminal behavior has traditionally been seen as being consistent with their aggressive, self-assertive character. This double standard also explains the tendency to medicalize women’s deviance and to see it as the product of physiological or psychiatric pathology. For example, in the late 19th century, kleptomania was a diagnosis used in legal defenses that linked an extreme desire for department store commodities with various forms of female physiological or psychiatric illness. The fact that “good” middle- and upper-class women would turn to stealing in department stores could not be explained without resorting to diagnosing the activity as an illness of the “weaker” sex (Kramar, 2011).

When feminist criminology emerged in the 1970s, the focus was mainly on how women were accounted for in criminological theories. Feminist criminologists recognized that theories of crime and deviance regarding women’s offending tended to take one of three paths: (1) theories were openly misogynistic, negatively portraying women or situating them as “less than” men; (2) theories were gender-blind and completely ignored gender; or (3) theories took an “add women and stir” approach, meaning that the theory was primarily about men and assumed explanations for crime and deviance could be applied to women without question. Most criminological theories were silent on the victimization of women.

The many androcentric (male-centered) explanations for crime and criminality were mainly the work of theorists who were men. In response, feminist criminologists demanded a centering of gender as a key factor in understanding crime and criminality. Here we see the scholarship of ground-breaking feminist criminologists like Meda Chesney-Lind, Carol Smart, and Karlene Faith and the theorists and criminologists they have inspired, such as Elizabeth Comack, Gillian Balfour, and Joanne Belknap.

Current feminist criminology points to the role of patriarchy, colonialism, capitalism, and other social structures and relationships in our broader society as contributing to the disproportionate victimization of women. While patriarchy privileges men and their experience over women and their experience, third-wave feminism and critical race scholars established the vital importance of intersectional analyses of gender-based violence (Bruckert & Law, 2018).

Feminist criminology challenges social institutions within the criminal justice system to acknowledge and address the disproportionate impact of gender on women’s victimization. Feminist criminologists acknowledge that due to systemic factors, including violence, colonialization, and inequality, women are much more likely to suffer from childhood sexual abuse than men. They also acknowledge that alcohol or substance use is often a coping mechanism that may result in increased likelihood of contact with the criminal justice system. Lastly, they understand that there is a high proportion of incarcerated women who have experienced trauma (Comack, 2018; Shdaimah & Wiechelt, 2013). In essence, feminist criminologists ask us to examine how the criminalization of women is intertwined with the victimization of women. The question becomes: how can the criminal justice system respond to the unique needs of women given this victimization-criminalization continuum (Chesney-Lind & Pasko, 2004; Comack, 1996)?

Activity: Intersectionality and Understanding Identity

“Intersectionality promotes an understanding of human beings as shaped by the interaction of different social locations (e.g., ‘race’/ethnicity, Indigeneity, gender, class, sexuality, geography, age, disability/ability, migration status, religion). These interactions occur within a context of connected systems and structures of power (e.g., laws, policies, state governments and other political and economic unions, religious institutions, media). Through such processes, interdependent forms of privilege and oppression shaped by colonialism, imperialism, racism, homophobia, ableism and patriarchy are created”]

(Hankivsky, 2014).

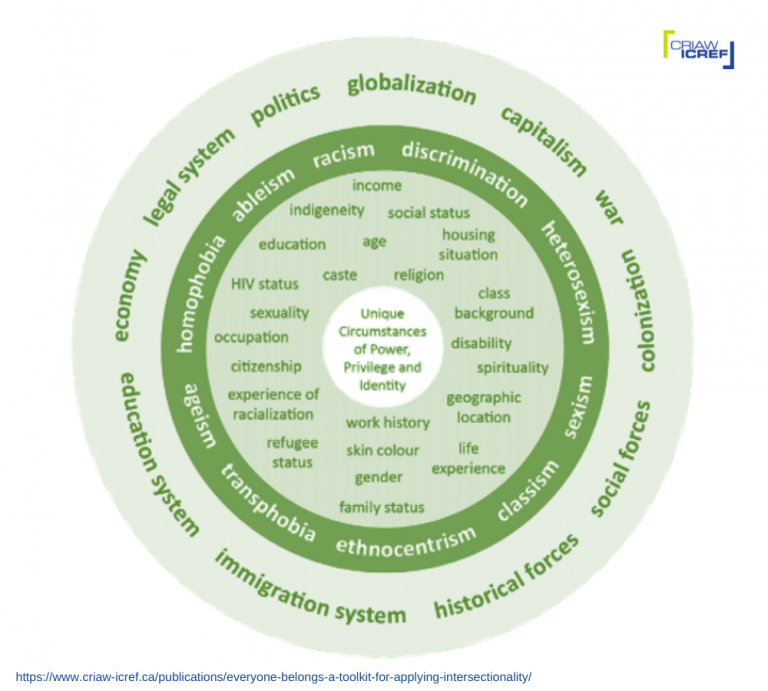

Study the diagram in figure 8.7 from the Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women (n.d.) that illustrates the concept of intersectionality. Each circle represents different parts of who someone is and how they experience the world, including unique personal circumstances (center), aspects of identity (second circle), prejudice and discrimination that impact identity (third circle), and larger forces or structures that maintain exclusion (outer circle).

Considering your own intersectional identity—including but not limited to, your gender, race/ethnicity, country of origin, religion, sexual orientation, age, disability, socioeconomic status, geography, and migration status—how might your position impact your thoughts about or approach to the study of criminology and criminal justice? From an intersectional lens, how might your experiences shape your understanding of criminological theories?

Note: You are welcome to share information about your intersectional identity in your answer, but you are not required to do so. However, you should consider your personal position, obstacles, and privileges when answering these questions and think deeply and honestly about how your experiences may differ from those in other positions.

Female Delinquency

A consistent finding in crime data is that boys and men commit more crime than women and girls. Even though women and girls have increasingly become more involved in the criminal justice system, this finding persists. Some theorists have evaluated this issue from a feminist perspective to make sense of it.

American sociologist John Hagan and his colleagues wanted to figure out why boys committed more delinquent acts than girls and decided to look at their behavior in the family context. They developed power-control theory (Belknap, 2015), which outlines the role of social control in accounting for gendered differences in crime. They theorized that the gendered power dynamic between parents is often replicated with their children. In a patriarchal home, children are socialized into gender roles in which boys are encouraged to take risks and given more freedom, while girls are more restricted in their activities and socialized to be obedient and quiet. According to their theory, instrumental controls in the form of supervision and surveillance and relational controls in the form of an emotional bond with the mother are imposed more on daughters than on sons. In such households, girls have fewer opportunities to engage in deviance.

According to Hagan and colleagues, in egalitarian households where power is shared equally between parents, relatively equal freedoms and levels of parental supervision were given to daughters and sons, which allowed for more opportunities for girls to engage in deviant behavior (Belknap, 2015). Note that while this theory does at least attempt to explain the offending of women, it is not without its critics. Of particular concern is how the theory blames mothers who work outside of the home for their daughters’ delinquency (O’Grady, 2018). The theory has also been criticized “for its simplistic conceptualization of social class and the gendered division of labor in the home and workplace, and for its lack of attention to racial/ethnic differences in gender socialization and to single-parent families, most of which are headed by women” (Renzetti, 2018, p. 78).

American Meda Chesney-Lind and Australian Kathleen Daly are prominent feminist criminologists who also focus specifically on women’s delinquency. Daly identified three areas to consider when trying to understand the gender differences in juvenile offending behavior:

- Gendered lives: Girls are socialized in accordance with accepted gender roles, and this impacts their daily lives and experiences with law-breaking.

- Gendered pathways: Girls’ engagement in crime follows a path that differs from that of boys and moves from victimization to substance abuse and then to acting out.

- Gendered crime: Street life, sex, drug markets, and other criminal opportunities are structured in gendered ways that impact the type of crime available to and engaged in by girls.

Relatedly, Chesney-Lind (1987) emphasizes that our world, including the criminal justice system, is patriarchal and controlling of women and girls. She put forth four propositions in the feminist theory of delinquency:

- Girls are often physically and sexually abused. Their gender uniquely shapes this victimization and their response to the victimization.

- Those who victimize girls and women are typically men and are able to invoke informal controls like gender roles and formal controls like police involvement to keep these women and girls, especially daughters, at home where they are vulnerable.

- Girls will often run away from home to escape victimization but are then left with few opportunities once they become “runaways,” including being unable to enroll in school and having limited job opportunities.

- Girls who have escaped abusive homes and are now runaways become forced to engage in criminal activities, especially those that exploit their sexuality, to survive.

Daly and Chesney-Lind contend that gender matters when studying crime and victimization because girls and women move through the world differently than boys and men do (figure 8.8). Girls are socialized to be nice and tend to internalize their problems, while boys are socialized to not back down and often externalize their problems. Consequently, girls’ involvement in crime typically starts from substance use as a means of coping with victimization, especially sexual victimization. For example, a 2022 report from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) showed that the majority of sexual abuse victims were girls, with their victimization rates ranging from 55% of all victims under the age of 1 year old up to 87% of victims age 17 years old (DHHS, 2024). The fact that society places value on girls and women for their sexuality means that sex work may be the most accessible, or forced, criminal opportunity for runaway girls and those trying to survive on the streets. Thus, victimization becomes intricately tied into the cycle of offending.

Daly and Chesney-Lind’s frameworks provide nuanced insight into the way girls experience victimization, crime, and treatment by the system. Chesney-Lind’s intersectional approach, which considers the impact of race, class, and gender in shaping girls’ pathways into delinquency, highlights systemic inequalities that push marginalized girls toward survival strategies that may involve crime. Together, Daly and Chesney-Lind’s work challenges traditional criminological perspectives that often overlook or misinterpret offending by women. By understanding the complex interplay of social, economic, and gendered factors, policymakers and practitioners can better tailor interventions that address the root causes of delinquency in women, promote equity in the justice system, and support pathways to rehabilitation and community reintegration for girls at risk.

Applying the Feminist Perspective: Control-Balance Theory

Although some theories, like those used to explain girl’s delinquency, may arise directly from feminist criminology and center gender in their explanations, others may be reevaluated or applied using a feminist perspective. In other words, feminist criminologists sometimes utilize traditional criminological theories by applying a feminist lens to who or what they study. Let’s take the control-balance theory to use as an example of how this might occur.

Coined by criminologist Charles Tittle (1995), control-balance theory is a blend of social control theory and containment theory from Chapter 7. This theory focuses on the control someone is under as well as the control they hold over themselves. Too much control can be just as dangerous as too little. An individual’s control ratio is the amount of control a person is subject to versus the amount of control a person exerts over others. In this theory, the control ratio is used to determine someone’s risk of deviance. The importance of the control ratio is that it is believed to predict not only the probability that one will engage in deviance but also the specific form of deviance.

High levels of control are called a “control surplus,” and low levels are called a “control deficit.” According to Tittle, someone with a control surplus is able to exercise a large amount of control over others. Those who are overly controlled by someone else experience a control deficit. A situation that highlights someone’s control imbalance will prompt them to correct or rebalance their control ratio. Such a situation may lead to crime, especially if the person feels humiliated about the imbalance.

Although this theory was not initially formed within a feminist perspective and did not seek to address gendered crime issues, it is compatible with a feminist approach when applied accordingly. For example, in cases of intimate partner violence, there is often one person with a control surplus. From a feminist criminological lens, patriarchal societies ensure that men have a control surplus, and control-balance theory may be able to shed light on gendered criminal behavior. When men use physical force, emotional manipulation, or financial control over women, control-balance theory might explain the behavior as an exertion of control to maintain balance when the man perceives it to be lacking.

Ultimately, feminist criminological approaches to explaining crime (and victimization) among young girls and women recognize gendered culture and patriarchal institutions in society as having a significant impact on how they experience victimization, offending behavior, and the criminal justice system. Nearly all of the initial research conducted to establish or support the theories discussed in previous chapters of this textbook exclusively or predominantly included boys and men. Regardless of their specific theoretical concepts, feminist approaches center gender and grapple with the various ways that gender impacts behavior and treatment in the criminal justice system.

Learn More: Canada’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG)

The epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls is an issue across the globe, and it has prompted a movement in countries such as the United States, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia (figure 8.9). This section will provide a case study in the Canadian context.

As demonstrated throughout this chapter, feminist criminology highlights the different pathways to offending as well as myriad ways in which women are uniquely victimized. This approach also calls attention to the intersectionality of gender with other forms of identity. The case of murdered and missing Indigenous women offers one example of this intersectionality reflected in the criminal justice system. Red Dresses on Bare Trees is an edited collection of stories and reflections by “authors with good minds, hearts and spirits (fuelled by good intentions)” (Hankard & Dillen, 2021, p. v) that address through stories and reflections the challenging human rights violations faced by Indigenous women and the plight of the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) of Canada. The text provides reflections of those affected by the pain of MMIWG and honors their voices and their stories. If you are interested in reading the stories, you can find them in the book Red Dresses on Bare Trees: Stories and Reflections on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls [Website].

In Decolonizing the Violence Against Indigenous Women, Jacobs (2017) argues that decolonization must include a goal of returning safety and respect to Indigenous peoples, especially Indigenous women and girls, and the stolen lands settlers occupy (Jacobs, 2017, p. 51). Many provincial and national inquiries have produced reports that examine the circumstances of Canada’s Indigenous peoples that are the direct consequence of its colonial history and the intergenerational trauma associated with Canada’s past and present. This includes a history built on Eurocentric norms and systems; the removal of Indigenous children from their families and their placement in residential schools, which were often fraught with physical, sexual, and psychological abuses; and the Sixties Scoop, during which Indigenous children were placed in foster care. But make no mistake: the colonial oppression of, and violence against, Indigenous peoples is ever present in Canada today.

The first public inquiry into Canada’s treatment of its Indigenous peoples followed the Oka Crisis in the summer of 1990, which drew international attention and forced the federal government to seriously consider its historical and ongoing treatment of its First Peoples. The Oka Crisis was a dispute over a golf course on the lands and burial grounds of the Kanien’kéhaka (Mohawk) in Québec and involved heavy military enforcement. The National Film Board of Canada produced the award-winning documentary Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, which detailed the 78 day standoff that resulted in two fatalities.

Although the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples’ (RCAP) report (Hamilton & Sinclair, 1996) does not focus specifically on Indigenous women and girls, it provides a detailed history of the colonial practices that harmed Indigenous peoples for centuries, with a focus on including Indigenous voices (Hamilton & Sinclair, 1996). At the same time, the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) began demanding action to address the continued disappearance and murder of Indigenous women and girls across Canada (Tavcer, 2018). According to the final report of the National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG): Reclaiming Power and Place (2019), the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) now confirm 1,181 cases of “police-recorded incidents of Aboriginal female homicides and unresolved missing Aboriginal females” between 1980 and 2012.

Between 1996 and 2019, many other commissions and inquiries addressing MMIWG have issued similar reports that highlight the dangers of being an Indigenous woman or girl in Canada. Several of the inquiries have focused on British Columbia because it has the highest proportion of MMIWG. The Highway of Tears—a 725 km corridor of highway stretching from Prince Rupert to Prince George, British Columbia—is where at least 30 Indigenous women and girls have gone missing since 1974. British Columbia is also the site of serial killer Robert Pickton’s farm where DNA from 33 female victims was found, 12 of whom were Indigenous.

It is time for meaningful action to address the ongoing oppression and systemic racism against Canada’s Indigenous peoples. We continue to see the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples—women in particular—in all aspects of the Canadian criminal justice system, as both people who commit offenses and victims. In 1996, the RCAP asked “Why in a society where justice is supposed to be blind are the inmates of our prisons selected so overwhelmingly from a single ethnic group?” (Hamilton & Sinclair, 1996). How is it that we continue to ask the same question today?

Check Your Knowledge

Licenses and Attributions for Feminist Criminology

Open Content, Original

“Activity: Intersectionality and Understanding Identity” by Jessica René Peterson is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Applying the Feminist Perspective: Control-Balance Theory” by Jessica René Peterson and Curt Sobolewski is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Feminist Criminology Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Feminist Criminology is adapted from:

- “Foundations of Feminist Criminology“, Introduction to Criminology by Dr. Rochelle Stevenson, Dr. Jennifer Kusz, Dr. Tara Lyons, and Dr. Sheri Fabian is licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include shortening for clarity and brevity, tailoring to the American context, and combining with other topics.

- “Sexualised Violence“, Introduction to Criminology by Dr. Rochelle Stevenson, Dr. Jennifer Kusz, Dr. Tara Lyons, and Dr. Sheri Fabian is licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include shortening for clarity and brevity, tailoring to the American context, and combining with other topics.

- “Reading: Conflict Theory and Deviance“, Introductory Sociology by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include shortening for clarity and brevity, adapting to a criminological context, and combining with other topics.

- “Critiques of Existing Criminological Theory“, Introduction to Criminology by Dr. Rochelle Stevenson, Dr. Jennifer Kusz, Dr. Tara Lyons, and Dr. Sheri Fabian is licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include shortening for clarity and brevity, tailoring to the American context, and combining with other topics.

“Female Delinquency” is adapted from “Criminalisation of Women“, Introduction to Criminology by Dr. Rochelle Stevenson, Dr. Jennifer Kusz, Dr. Tara Lyons, and Dr. Sheri Fabian, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include expanding, tailoring to the American context, and adding discussions of Daly and Chesney-Lind.

“Learn More: Canada’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG)” is adapted from “Treatment in the Criminal Justice System“, Introduction to Criminology by Dr. Rochelle Stevenson, Dr. Jennifer Kusz, Dr. Tara Lyons, and Dr. Sheri Fabian, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include shortening for clarity and brevity and contextualizing the problem in a global setting.

Figure 8.6. “Six Feminist Perspectives” is adapted from “Foundations of Feminist Criminology“, Introduction to Criminology by Dr. Rochelle Stevenson, Dr. Jennifer Kusz, Dr. Tara Lyons, and Dr. Sheri Fabian, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted. Modifications by Jessica René Peterson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, include condensing material into a chart form for easier readability.

Figure 8.8. “Princess or Jedi Pink and Blue Cake” by Sweet-Tooth Cakes and Cupcakes is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 8.9. “Juarez-MMIWG-1” by Seattle City Council is licensed under the CC BY 2.0.

All Rights Reserved

Figure 8.7. “CRIAW-ICREF’s Intersectionality Wheel” by The Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women from Everyone Belongs: A Toolkit for Applying Intersectionality is included under fair use.