10 Ethical and Legal Issues in Education

“A child born to a Black mother in a state like Mississippi… has exactly the same rights as a white baby born to the wealthiest person in the United States. It’s not true, but I challenge anyone to say it is not a goal worth working for.”

Thurgood Marshall

Learning Objectives

- Define a code of ethics in education

- Explore legal protections for students US schools

- Explore legal protections for educators in US schools

- Describe foundational legal cases that impact US schools

Pause and Ponder – Can the teacher use this book?

A high school English teacher is planning to have his students read The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison. Set during the Great Depression, the main character searches for her identity and sense of self. In addition, there are themes of race, class, exploitation, and sex in the novel. Can the teacher include this book in his reading list for the year even though it was banned by the Parent Teacher Association (PTA)?

Actually, there is no clear answer for this teacher. The National Education Association (NEA) Code of Ethics suggests a standard of reasonableness. When making decisions as a teacher, ethics oftentimes presents a ‘gray area’ and does not always provide a definitive resolution.

In this chapter, we review the roles and responsibilities of teachers in today’s public schools as they relate to ethical and legal issues in education. We explore ethical teaching, along with legal parameters, established through case law and set up in the U.S. Constitution and its amendments. Rights for both teachers and students are examined, and current implications are discussed.

Ethics in Education

When you think of your favorite teacher, it is not often that you consider whether he or she was ethical. Yet professional ethics and dispositions, as well as the legal responsibilities of teachers, are central in defining how students view their favorite teacher. Ethics provides a foundation for what teachers should do in their roles and responsibilities as an educator. It is a framework that a teacher can use to help make decisions about what is right or wrong in a given situation.

Teachers are not only responsible for their students but also in the long term, for the growth and development of their community. Today’s students are tomorrow’s leaders, workers, policy makers, thinkers, dreamers, and voters. It is not a stretch to say that teachers really do hold the future in their hands. To that end, developing an ethical and liberatory approach to teaching is crucially important.

Deeper Dive: Liberatory Education

Liberatory education has been discussed in a prior chapter. Here is a reminder – Liberatory Education

Video10.1

10.1 What is a Code of Ethics?

Most professions have a Code of Ethics that binds its members together through shared values and purpose. This professional Code of Ethics is a widely accepted standard of practice that outlines the accountability of its members to those they serve as well as to the profession itself (Benninga, 2013). Here are some examples of Ethics Codes:

Varying Codes of Ethics in Educational Organizations

| Educational Organization | Code of Ethics |

| National Educational Association (NEA) | The educator recognizes the magnitude of the responsibility inherent in the teaching process. The desire for the respect and confidence of one’s colleagues, of students, of parents, and of the members of the community provides the incentive to attain and maintain the highest possible degree of ethical conduct (NEA, Code of Ethics, 2019). |

| Association of American Educators (AAE) | The professional educator endeavors to maintain the dignity of the profession by respecting and obeying the law, and by demonstrating personal integrity (AAE, Code of Ethics, Principle II, 2019). |

Each of the statements on ethics from these teacher professional organizations complements the others, outlining expected behaviors and dispositions, identifying professional intent, and solidifying commitments that are expected from educators in their roles representing public schools throughout the state and nation.

Let’s see how a Code of Ethics could impact the scenario that opened this chapter. Recall that the high school English teacher wanted to include a controversial book on his reading list for the school year that has been banned from use. He believes this book will provide a rich experience for his students and provide stimulating class discussion and debate around identity and race. In determining whether or not to incorporate the text, the teacher must ask himself if he is truly presenting different points of view. In so doing, the teacher is adhering to the National Education Association (NEA) Code of Ethics, specifically Principle I, Item 2:

Principle I: Commitment to the Student:

The educator strives to help each student realize his or her potential as a worthy and effective member of society. The educator therefore works to stimulate the spirit of inquiry, the acquisition of knowledge and understanding, and the thoughtful formulation of worthy goals.

Item 2:

In fulfillment of the obligation to the student, the educator shall not unreasonably deny the student access to varying points of view (National Education Association, 2019, para. 8).

With this Code of Ethics in mind, this teacher could argue that reading this book stimulates the spirit of inquiry and knowledge acquisition, and not reading the book would unreasonably deny the students access to varying points of view.

Code of Ethics in Action

Consider the ethical dilemmas that are present every day in the classroom and the ethical decisions that a teacher must make. Consider how each decision that a teacher makes impacts the functioning of the school, the well-being of the students, and the personal goals of the teacher in pursuit of the profession of teaching and supporting student learning.

There is not always one right “answer” in any given situation. A Code of Ethics provides guidelines to help guide your decision making and teaching practice. It helps with what you should do. It does not provide specific directions on what to do or even how to do it.

Ethical decisions take place every day in our classrooms. Oftentimes, you may believe that treating students equally is an ethical approach. But if you go into a classroom, you may notice a teacher calling on a shy student and not calling on another student who usually dominates the discussion. Is this equal? Is this fair? These are two different things. The teacher is clearly treating the two students differently. The NEA Code of Ethics guides your teaching behaviors by placing your students at the center of your practice. Always consider that you must treat all students equitably, not necessarily the same or equally.

Critical Lens – What is Equity and what is the difference with Equality?

What is equity? – It is the continual process of looking for and removing things that create disparity. Equity requires providing people what they need to succeed in the proportion to which they need it. Equity can not be achieved with a neutral approach. Meeting students where they are at is an equitable approach.

Equity vs Equality

Video 10.2

A professional Code of Ethics governs a teacher’s relationships, roles, conduct, interactions, and communication with students, as well as families, administrators and the larger community. It provides educators with a way to regulate personal conduct and ethical decision making. It does not tell a teacher why they should do something. Having an informed awareness of statutes, laws, and other legal influences will assist you in defining your role as an ethical teacher who is also fair and responsible. It is essential for an effective educator working under any code of ethics to understand diverse student needs and deliver equity in practice.

Pause and Ponder

What are your own personal ethical beliefs having to do with education? What might be some ways to practice no harm? What situations could you envision in teaching that would require ethical decision-making?

One topic that’s not commonly covered in codes of ethics for teachers is a continuous commitment to examining and addressing one’s own biases. As mentioned elsewhere in this text, as humans, our bias reflects the implicit values and beliefs of the community and society. Our biases influence how we interact with students, their experiences in school, and even their outcomes and opportunities. Here’s an example of how this works. Recently, researchers found that even in online classrooms, teachers’ racial and gender bias can influence whether students get referred to gifted programs or special education programs.

Activity – Personal Biases

Watch this film and consider your own biases

Video 10.3

- What does my headscarf mean to you? with Yassmin Abdel-Magied

- Provide an example of a time personal bias impacted a decision in your work.

- What might you do as a teacher to continually assess whether and how you are bringing your personal biases into the classroom?

10.2 Education and the Law

What does discrimination look like in the classroom?

Discrimination in the classroom can be overt or covert and can take many forms. The following list provides broad ways that discrimination could be identified in the classroom.

- Treating people inequitably based on social categories, e.g., race, nationality, language (see more below about Protected Classes)

- Treating people unequally and/or oppressively because they belong to a marginalized group

- Behavior that results in subordinating or continuing to subordinate a marginalized group

Protected Classes and Federal Laws Protecting Individuals’ Civil Liberties

Federal laws explicitly protect certain classes of people, called protected classes, from discrimination. This means that it is illegal for any federal or state organization or public entity to discriminate against someone based on their protected class(es) status.

Critical Lens – Protected Classes

- Race – The socially constructed categorization of people based on racialized characteristics

- Color – The amount of melanin in a person’s skin determining their coloring

- National Origin – The nation where a person was born or where their ancestors come from

- Religion – The US Constitution gives people the right to freedom of religion and schools must accommodate the religious needs of students

- Sex – Gender-based policies that favor a specific gender are prohibited in schools. It is important to note that the state of Oregon has further laws that extend the protected class status to individuals based on sexuality and gender identity

- Marital Status – A school cannot discriminate against an individual based on their marital status

- Disability – The American with Disabilities Act (ADA) defines disability as any mental or physical impairment that limits major life activity

- Age – Age discrimination particularly relates to personnel in schools in that age cannot be a discriminatory factor in hiring, retaining or compensating employees

10.3 The U.S. Constitution and the 1st and 14th Amendments

Significant, ground-breaking court cases have influenced the practice of public schools throughout history and many verdicts have come from the U.S. Supreme Court. The majority of these cases focus on the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

The First Amendment of the U.S Constitution

It addresses the freedom of speech, religion, press, and the right to petition the government, and assemble peaceably (U.S. Constitution, First Amendment).

It states:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution ratified in 1791

Courts have been called to answer questions about the freedoms outlined in the First Amendment as they relate to teachers and students (American Library Association, 2006). Cases include the dismissal or suspension of personnel due to issues such as religious clothing, political symbols and speaking profanity at a school assembly .

Critical Lens – Tinker v. Des Moines

Tinker v. Des Moines

A school district in Des Moines passed a rule that students could not wear armbands to protest the Vietnam War. In Tinker v. Des Moines, the students argued that the district was violating their right to freedom of speech and the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the students. The Court also ruled that the only time school or school personnel could impinge on a student’s right to freedom of speech was if they could show that the behavior significantly interfered with “the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school.”

The Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., has settled many cases in our country’s history about how the U.S. Constitution, especially the First and Fourteenth Amendments, relates to public schools.

In Bartels v. Iowa (1923), the Supreme Court upheld a conviction of a teacher for teaching German to students. The English-only movement in schools that many attribute to contemporary times has its roots in some of the xenophobia that was used to justify World War 1. Later, In Griswold v Connecticut (1965) the court ruled that the right to teach foreign languages is protected by the First Amendment of the constitution.

The First Amendment rights provides teachers a degree of protection for in-class curricular speech. In Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District No. 26 v. Pico by Pico (1982), the Supreme Court found that the school board could not restrict certain books in the school system’s libraries because school board members disagreed with the content. Doing so was found to be a violation of the First Amendment and our protection with regards to freedom of speech.

Critical Lens – First Amendment Protections

- Freedom of speech is the right for individuals to speak freely without fear of censorship or reprisal from the government. The right to freedom of speech applies to both school personnel and students. For example, a teacher might bring legal action against a school if they are fired for talking about issues of public interest like a school board election. Another example is that students have the right to exercise their freedom of speech through protests or messages on their clothing.

- Freedom of exercise limits government interference and actions on individuals’ religious beliefs and individuals’ practices in relation to their religious beliefs

- Freedom of press protects print and electronic media from censorship. This may apply in certain cases to school newspapers and media releases.

- Freedom of assembly ensures the right that people can gather together peacefully as long as they are not engaging in illegal or criminal activities. This may apply in certain cases to students’ right to form and participate in group protests in schools.

These rulings have come into conflict over the years due to school systems also having the right to set the curriculum. This school system precedent was upheld in Krizek v. Board of Education (1989) when a non-tenured English teacher showed an “R”-rated film to high school students and her contract was not renewed. The district court found that the teacher’s First Amendment rights were not violated, rather the school board acted reasonably in determining that the film was inappropriate. (We’ll discuss tenure in more depth later in this chapter.)

The Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution

It guarantees equal opportunity for due process and equal protection to all who live within the jurisdiction of the United States. This amendment was ratified in 1868 and written specifically to protect the rights of recently freed enslaved people.

Ensuring that this opportunity applies to all persons, it reads:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution ratified in 1868, Section 1

The Fourteenth Amendment provides a guarantee that a state cannot take away constitutional rights or privileges as identified in the U.S. Constitution (National Constitution Center, 2020). It has three primary clauses:

- The Incorporation Doctrine extended the rights guaranteed in the Bill of Rights to state governments. This means that any state laws that violate the rights granted by the Constitution at the federal level would be overturned.

- The Due Process Clause affirms that states may not deny any person “life liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

- The Equal Protection Clause establishes that states may not “deny to any person (citizen or non-citizen) within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Both the Due Process and the Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment significantly impact education. The Equal Protection Clause is examined throughout this chapter as it relates to foundational legal cases, racial issues, and LGBTQ+ rights and discrimination. Next, we will consider how the Due Process Clause affects educators and students.

Activity – Scenario

Which legal protections might apply to this case?

Soledad Garcia was born with Cerebral Palsy in Texas in 1955. She had no access to schooling and her Mexican-American parents could not afford to send her to a specialized facility and so she stayed at home. Which of the following protections might have helped Soledad’s family as they advocated for her education?

10.4 What Federal Laws Protect Students and/or Educational Personnel’s’ Civil Rights?

The Civil Rights Act of 1964

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin by constraining private, non-government parties from discriminatory behavior in any program or activity that receives federal funds, e.g., schools and school related programs. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act mandates that it is unlawful for employers to discriminate against an individual in hiring, retention, and compensation because of the individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

The Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA)

IDEA was enacted in 1975 to ensure that children with disabilities had access to a free appropriate public education beginning at age 3 through age 21. The law provides guidance to states and school districts about special education services. One important mandate from the 2004 reauthorization of IDEA provides guidance to states and school districts to analyze and remediate the overrepresentation of racially, ethnically, culturally, and/or linguistically marginalized students in special education services.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)

FERPA was written to ensure the privacy of students’ educational records. It applies to any school or district that is receiving federal funds. FERPA is covered in more detail later in this chapter.

Video 10.4

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972

Title IX prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in programs and activities that receive federal funds, including schools. Some example provisions relate to discrimination on the basis of pregnancy, participation in athletic and/or STEM activities, hiring based on gender, and/or sexual harassment.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973

Section 504 prohibits employment discrimination against an individual with a disability when they can perform the essential job functions with reasonable accommodations. This act focuses on employers in organizations receiving federal funding, including schools.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

ADA prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in employment, schools, transportation, public and private services, and accommodations. This law applies to all public entities whether or not they receive federal funding.

No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Title III – Every Student Succeeds Act

NCLB’s Title III mandated the creation of funding and support for school districts so that they could better serve students learning English as an additional language, often called English Language Learners (ELLs). The act created the Office of English Language Acquisition with a mission and budget to “close the achievement gap” between students learning English as an additional language and native-English speaking students.

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) was signed into law in 2015 (Every Student Succeeds Act, 2015). It replaces the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act that was enacted in 2002. ESSA requires states to be more accountable for the achievement of students within their public schools. Its purpose is to provide equitable opportunity for students with diverse backgrounds to include those living in poverty, minorities, special needs, and English language learners.

ESSA provides school districts more control in how they set education standards and determine consequences for low-achieving schools in their districts. States provide an accountability framework to the federal government that assures that all students receive a high-quality education. States are responsible for having an accountability plan and specifying the accountability measures that they and their school districts will follow (Lee, n.d.).

The state educational plan must include how each school within the state will:

- maintain academic standards;

- provide annual testing in grades 3-8 in reading and math;

- identify accountability measures that look at academic achievement, progress, English language proficiency, and high school graduation rates; and

- measure school success by kindergarten readiness, advanced placement coursework, college readiness, and chronic absenteeism or discipline rates (Every Student Succeeds Act, 2015).

Schools must provide to the federal government a plan that outlines how they will ensure that students learn and achieve in their schools. If underperforming in any of the above areas, schools must additionally present a plan for improvement.

For more information, you can visit the U.S Department of Education

Video 10.5

Critical Lens – No Child Left Behind: Two perspectives

What supporters said:

- Acknowledgement of the inequities between US public schools and that some schools had been failing kids for decades

- Federal government had to intervene to address such inequities and could do this through reauthorizing ESEA funding and prioritizing the following actions:

- Raise preparation requirements for teachers- make sure they are qualified

What critics said:

- Over-testing of students which causes students to disengage

- Teachers lost valuable teaching time

- Overreach of federal government

- Prioritized rote memorization and basic processes

- Publicly sanctioned schools, many of them minority serving, for not meeting established goals, thereby perpetuating negative stereotypes

- Ignored assessment frameworks that recognize multiple and

Food and Nutrition Services USDA Departmental Regulation 4330-2

This USDA regulation was established to ensure that programs, activities, and institutions that receive financial assistance from the USDA (including school cafeterias) comply with civil rights laws and do not discriminate against individuals based on their protected class status.

Activity – Reflection

In terms of Soledad, the student mentioned above, almost all of the legal protections mentioned here could have applied to her case but most notably IDEIA which provided significant access to students living with disabilities. Before 1975, if a student had a disability, they were excluded from the US educational system. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 advocated for racial justice and laid the foundation for other marginalized groups, including those who live with disabilities, to access education? Because of Soledad’s various marginalized identities, multiple laws bear on her situation.

Have More Questions about Federal Laws Related to Discrimination in Educational Environments? See the following resources:

- Race and National Origin Discrimination (Takes you to a US Department of Education page)

- Sex Discrimination (Takes you to a US Department of Education page)

- Disability Discrimination (Takes you to a US Department of Education page)

- Age Discrimination (Takes you to a US Department of Education page)

Due Process

For educators and students, due process requires considering whether a constitutional right has been infringed upon by the state, and then affords the accused student, teacher, school district or state the right to a fair and impartial trial. Generally speaking, the due process clause of the 14th amendment entitles students and educators to an impartial trial or hearing when certain constitutional rights are infringed by the state.

All members of the school community have the right to due process with the purpose of providing a fair trial. The central premise of due process is fairness. A school district can be sued if others believe the district acted in an unfair or unreasonable way. This legal argument can be made on behalf of a teacher, student, parent, or community member. Anyone who believes that they were unfairly or unreasonably impacted by a policy or procedure of the school can institute a legal case against the school.

In the Supreme Court case Hortonville Independent School District No. 1 v. Hortonville Education Association (1976), the Justices ruled that the school board was able to deliver due process in a reasonable manner when it fired teachers who went on strike after contract negotiations failed. The teachers were asked to return to work but refused. They were then terminated. The teachers argued that their dismissal violated their due process and should be reviewed by an impartial decision maker. The court did not agree, citing instead that the school board was viewed as the impartial decision maker, and they did not need to be independent from the issue.

Schools in the United States accept responsibility for children as they enter through their doors, and teachers have responsibilities that relate to educating students as well as providing physical, social, and emotional safety to all children, beyond teaching the required curriculum. Because of the diverse nature of schools, the U.S. court system helps to balance teachers’ and students’ responsibilities and rights.10.5 Foundational Legal Cases

Throughout U.S. history, there have been many notable court cases heard by the Supreme Court related to public education in the United States (National Constitution Center, 2015). Select foundational legal cases are highlighted below:

Examples of Foundational Legal Cases in Education

| Case | Decision |

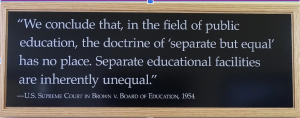

| Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) | Racial segregation was upheld, allowing states to segregate schools under the “separate but equal” doctrine. The Supreme Court upheld the segregationist doctrine of “separate but equal.” This discriminatory doctrine was applied in many aspects of public life, including schooling, for decades, as a result. |

| Brown v. Board of Education (1954) | This landmark Supreme Court case (Brown v Board)) overturned Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and addressed segregation of public schools on the basis of race. African American students who had been denied admittance to public schools argued that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment was violated. The justices agreed stating that “separate but equal educational facilities for racial minorities is inherently unequal”. |

| San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez (1973) | The justices ruled that education is not afforded protection under the Constitution. The Supreme Court also held that a school district is responsible for providing only a “minimum educational threshold” for students within their jurisdiction, as defined by the state, and which adheres to federal law. |

| Plyler v. Doe (1982) | The Supreme Court previously held that education is not a “fundamental right” because it is not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution nor the Bill of Rights, but reinforced that public education does have “a pivotal role in maintaining the fabric of… society and in sustaining … political and cultural heritage” of society. This ruling underscored the importance of public schools throughout the United States and held that all children within a state’s jurisdiction, whether legal or illegal, have the right to a public education, if a public education is provided by the state. |

Activity – Scenario Legal Case

Which Legal cases might apply to this situation?

Rebecca welcomed Moise Francois to Beavercreek Elementary. His mother had none of the usual documentation but she did have an ID card and a local address on a utilities bill which helped to establish that this was their elementary school. Rebecca knew that legally the schools never asked for social security cards or any other kind of immigration or naturalization paperwork due to the landmark Plyer vs Doe case. She also knew that she could place Moise in an ESL classroom for his first day which would help to ease him into the US school system. The school had a plan for its English Language Learners, as required by law per the landmark Lau vs Nichols case (both cases explained below).

Lau v. Nichols (1974)

A group of Chinese American students who were learning English as an additional language sued their school system for violating their 14th Amendment rights by not providing them enough language support to be successful in school. The Lau v. Nichols case was grounded in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as it discriminated against the students based on their national origin. The Court ruled in favor of the students and codified the civil right to be instructed in a language or through a method (such as ESL) that is understandable. The Court ruling laid the needed groundwork for the argument that national origin discrimination extends to language-based discrimination because language and national origin are inherently interconnected.

Deeper Dive – Federal Court Rulings Related to Discrimination in Educational Environments

Where Can I Find More Information about Federal Court Rulings Related to Discrimination in Educational Environments?

- Case Summaries Related to Protected Classes [Takes you to a United States Department of Justice page}

- The Stanford Equality of Opportunity and Education Project [introduction page] has curated this list of landmark US legal cases related to equality and opportunity in K-12 education

Throughout U.S. history, courts have become more involved in helping school districts make decisions that affect how localities and states conduct schooling (Thomas, 2019). As diversity increases throughout the United States, school policies and procedures continue to be challenged in our court systems. When pursuing legal action, the goal is to ensure that schools provide a fair and reasonable system of education for all students.

10.6 State Oversight

Each state must follow its respective State Constitution as well as the U.S. Constitution when defining the role and responsibilities of public schools within their state. Although education is a responsibility of the state, school districts have authority over their individual schools as it relates to curriculum and discipline. Rights are afforded to teachers in normal day-to-day functioning and when appealing grievances as it relates to such things as contracts, policies, denial of tenure, or suspension. Students must also adhere to this authority, unless it overrides a student’s constitutional rights.

States provide a wide range of oversight. They identify the minimum licensure requirements for educators. States also dictate what educators must do within that state to maintain their teaching licenses. State laws provide guidelines regarding how schools are organized based on funding. The legislature and Governor of each state allocate a certain amount of funding to school districts throughout their state. School districts then decide how those funds are spent. State legislatures and courts have intervened to help reduce funding disparities among poorer and wealthier school districts to better ensure that all students have equal access to education. States also create a state board of education, set-up school districts throughout the state, and establish school boards for each district. State laws also help to define student discipline and due process policies.

Examples of state involvement within public schools include:

- Creating school districts

- Allocating a budget to school districts

- Regulating schools throughout those districts

- Establishing the organizational structure for schools

- Defining policies and functions of the school

- Setting minimum curriculum requirements for schools

- Defining licensure requirements for educators, and

- Determining working conditions (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2020).

10.7 State of Oregon

If you are planning to get licensed in the state of Oregon, be sure to review the appendix on Civil Rights in Oregon.

In this section, you will learn about state laws that protect individual civil liberties and prohibit discrimination in educational settings. It is important that you are familiar with these laws and how they are applied in schools because teachers are considered “state actors” who act on behalf of the state.

Oregon Revised Statutes Relevant to Educational Settings

Oregon Revised Statutes (ORS) are codified laws of the State of Oregon. These are released every two years so it is important to know current laws related to discrimination in educational settings, and also that you can access the ORSs in future through this website

Protected Classes and State Laws Protecting Individuals’ Civil Liberties

In the State of Oregon, sexual orientation is a protected class. This extends the federally recognized protected classes to include sexual orientation. Sexual orientation is an individual’s physical and/or emotional attraction to other individual(s) or not. Some terms used to describe a person’s sexual orientation may be heterosexual (straight), gay, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, or asexual.

What Protections are Individuals Afforded Under The Oregon Constitution?

Article I of the Oregon Constitution is a bill of rights of the privileges, immunities, and authorities that may be legally and morally claimed by the citizens of the state within the bounds of reason, truth, and the accepted standards of behaviors. These rights include:

- Natural rights inherent in people

- Freedom of worship

- Freedom of religion

- No religious qualification for office

- No money to be appropriated for religion

- No religious test for witnesses or jurors

- Freedom of speech and freedom of the press

- Equality of privileges and immunities of citizens

- Assemblages of people; instruction of representatives; application to legislature

- Emigration

- Taxes and duties; uniformity of taxation

Deeper Dive – Information about Oregon State Laws Related to Discrimination in Educational Environment

Where Can I Find More Information about Oregon State Laws Related to Discrimination in Educational Environments?

10.8 Rights of Teachers

Teaching License

As discussed previously, the first step in becoming a legally-recognized teacher is to earn a teaching license. Each state has different requirements for earning a teaching license, as they define the specific dispositions, knowledge, and skills needed to obtain and maintain employment within a school in that state. In Oregon, the process is overseen by The Teacher Standards and Practices Commission. If you choose to complete an undergraduate or graduate degree program in order to teach, you will be working toward fulfilling the requirements of a teaching license in the state where your institution is located. Many states have reciprocity with other states’ teaching licenses, meaning that you can earn a teaching license in one state and still go teach in another one, as long as you also complete the requirements for earning a teaching license in that new state.

Contract

Once a teacher applies for and receives a job at a school, they receive a teaching contract. A teaching contract is a written agreement between the school system and the teacher and serves as a legal document identifying the roles and responsibilities for the teaching position. If the school board negotiated with a teacher’s union, then the policies and regulations of the union will also be identified in the contract. The teaching contract must be signed by the teacher, school, and ratified by the school board to be binding. The teaching contract is binding unless it is breached, should either party fail to perform as agreed during the time frame specified in the teaching contract. Be aware that each state has a different definition of the types of teaching contracts that are presented to teachers within the state.

Tenure

You may have heard of the word “tenure” in discussions about teaching contracts. Tenure protects teachers from arbitrary dismissal by school officials. Tenure derived from the Pendleton Civil Service Act of 1883, which was originally established as a merit system for government workers. Tenure rights for teachers in the United States date back to 1909, when the NEA lobbied for these rights. States define tenure laws for teachers in public schools, including elements like probationary periods and termination procedures. A school district can dismiss a tenured teacher for justifiable reasons such as noncompliance, immoral conduct, committing a crime, and insubordination. A teacher can also be dismissed for financial reasons, such as when a school district has a deficiency of funds.

Tenure does not guarantee a teacher a job for life, nor does it offer lifetime employment security (Hart, 2010). The focus of tenure is on supporting and protecting good teachers. It is an earned process that mandates due process. The benefits of a continuing contract or tenure are that a school must show cause in order to dismiss you because you, as the teacher, have due process rights. Advocates for tenure see its benefits for teachers in that it “significantly strengthens legal protections embodied in civil service, civil rights, and labor laws” and “protects a range of discriminatory firings not covered under race and gender anti- discrimination laws” (Kahlenberg, 2015, p. 7). In addition, teacher tenure has been shown to increase morale and overall teacher involvement within a school and collaboration among colleagues. Tenure affords teachers the ability to question and engage with school leadership as it relates to the functioning of a school and in building a strong school culture, which has been linked to increased academic achievement for students (Lee & Smith, 1996).

Presently, some states are changing their legislation as it relates to teacher tenure. The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) and Race to the Top grants through the U.S. Department of Education both require states to evaluate student achievement and teacher effectiveness. Certain state legislatures view teacher tenure as a barrier to these initiatives because it is more difficult for school districts to dismiss tenured teachers for poor performance, and as a result, relatively few tenured teachers are fired (Goldhaber & Hansen, 2010). Therefore, some states have begun to change tenure laws to adhere to the accountability requirements stipulated by the U.S. Department of Education as it relates to teacher evaluation and student achievement. As a result, some tenure systems have been removed or revamped with annual contracts requiring satisfactory performance. Florida, Indiana, North Carolina, and Kansas have eliminated tenure completely (Underwood, 2018). Additional states are also currently contemplating limiting or removing tenure for teachers.

Activity – Licensure Requirements

Look up licensure requirements for the state where you want to teach. What do you notice? What kinds of knowledge, training, and experience are you required to have? How is your understanding assessed before you are granted a license?

Unions and Participation in Professional Organizations

The National Education Association (NEA) and American Federation of Teachers (AFT) are two of the largest teacher labor unions and professional organizations in the United States at present. Both have been in existence for more than 100 years and support teachers, along with other school personnel. As unions, both organizations support their members with collective bargaining, whereby they work alongside teachers as they negotiate with their respective school districts to resolve disputes, as well as to lobby Congress for state and federal legislation that would impact educational related issues, including teacher rights and responsibilities. In some states, teacher unions will support your right to strike as a means of collective bargaining.

You can join the union that is present in your school or even start one, but since not all states recognize unions, the NEA or AFT may not be able to assist you with collective bargaining or school board negotiations, depending on your state of employment. Collective bargaining is legal in Oregon and Washington. Collective bargaining is illegal in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Texas, and Arizona. You may hear these referenced as “right to work states,” which means that employees have a right to work without being forced to join a union. Even so, each professional organization provides support, a rich network of educators, and professional development around issues and opportunities that can be beneficial for your teaching practice.

It is not often that educators are permitted to strike because they are employed by the state and are considered vital to public service. Still, some teachers do strike regardless of state laws that may prevent them from striking, as we saw in 2018 in West Virginia, Kentucky, and Oklahoma. When teachers go on strike, the impacted school board can obtain a court injunction to order teachers back to the school and teachers can lose pay for each day on strike. In many states, they can also be dismissed from their teaching positions for striking.

Activity – Advocacy

You may have heard of the #RedforEd movement, which involves teachers striking or protesting in many different states as a way to advocate for students. Watch this video to learn more about this movement from the National Education Association (NEA)

Video 10.6

Academic Freedom

Many teachers consider academic freedom to be a constitutional freedom outlined by the First Amendment. Because a teacher is a state employee and has signed a legally binding teaching contract, the teacher has a legal obligation to adhere to the rules and regulations identified by the school board and the laws of the state and federal government. A teacher represents the school and cannot do whatever they want in the classroom. Likewise, a teacher does not have complete freedom of speech to say whatever he or say wishes either. All teachers must follow guidelines represented in their teacher contract and the policies and procedures of the school board.

While the legal system has afforded teachers the right to select appropriate class materials, the educational purpose, the age and sophistication of students, and the context and length of time to complete assignments must all be considered. For example, if you wanted to teach the muscular system in human anatomy in your sixth grade science curriculum, but this content is not taught until tenth grade, you would not be able to change the curriculum framework set by the school district per your teaching contract.

If an activity aligns to your curriculum framework and you have followed the guidelines set forth by the school board, you could, for example, have a speaker come into your classroom to talk about an aspect of your curriculum or use an article published in the newspaper. Doing so would not be in breach of your contract. As you prepare for class instruction, consider your assigned curriculum, review school policies, and ask your school principal or other mentor teachers for guidance.

Academic freedom basically refers to the freedom of teachers to communicate information and share curricular material, without legal interference. In many cases, teachers were allowed a fair amount of academic freedom in creating and teaching their coursework. However, this has been notably changing in a highly politicized and divided nation.

Freedom of Speech and Expression

Pause and Ponder – Teacher Rights

Imagine a teacher published an opinion piece in the local newspaper. In the editorial, they were very critical of a policy that the school board had just passed. They also included many allegations that were not accurate. The community reacted very strongly on both sides of the issue. What rights does this teacher have for freedom of expression outside of their position as a teacher in this school district?

Outside of the classroom, freedom of expression for a teacher has been challenged in the court system if administration or general public determined that the speech or behavior was disruptive to the effectiveness of a school. Because a teacher has a professional responsibility to their school, educators must be careful about what they say, both at school and outside of school. It is also important for teachers to be mindful about what they post on social media, even if it is their personal account.

In the Pickering v. Board of Education (1968) case, the Supreme Court reversed a lower court ruling and found that the teacher’s First Amendment right to free speech had been violated after he was dismissed by the school board for writing and publishing a letter in the local newspaper criticizing the board. The court held that teachers were able to voice concerns, even if those concerns were unfavorable to the school, as long as the regular school operations were not disrupted. In the case, the court’s opinion was that the plaintiff’s First Amendment rights to free speech were not lost because a school district believes the speech is not in its “best interest.” After this ruling, the teacher in this case was reinstated to his position.

This influential case regarding First Amendment rights and freedom of speech for public school teachers established precedent that public employees have the ability to speak out on issues of public concern, even as state or government employees. Even so, the rights of public employees continue to be challenged in the U.S. court system.

In Connick v. Myers (1983), the Supreme Court again reversed a lower court decision and ruled that speech of public employees is protected only when they speak on matters of public concern. The case results here showed that the rights of public service employees must be balanced between matters of public importance and an employer’s interest to maintain a disruptive free workplace.

Similar to freedom of speech, a teacher’s freedom of expression can also be called into question as it relates to personal presentation and dress. Court cases surrounding dress code requirements established by school boards and imposed on teachers in their local schools have established some legal precedent, but this also continues to be a hotly debated topic. As a public school teacher, can you exercise your own ‘personal liberty’ in how you dress?In East Hartford Education Association v. Board of Education (1977), a public school teacher was reprimanded for failing to wear a necktie while teaching an English class. Joined by his teachers union, he sued the board of education on the basis that the admonishment for the dress code violated his rights to free speech and privacy. This case was heard in the U.S. Court of Appeals who found that the school board was justified in imposing the dress code. As a teacher and public servant in a position of trust, the court felt that this professional requirement and overall governance by the school board on the appearance of its teachers was warranted.

For many teachers and students alike, dress and personal appearance is considered a freedom of expression. Geographic diversity and individual school culture can also be a factor in what is allowed or not allowed as it relates to dress codes in schools across the United States (Sternberg, n.d.). What is acceptable in southern California may or may not be in West Virginia or Vermont. School principals often become the main authority for ensuring compliance (Waggoner, 2008). A standard of reasonableness is useful when crafting a successful dress code, along with clarity of language and flexibility dependent on the situation to determine appropriate dress and professional presentation. Review the dress code for your school and district to ensure that you are in compliance.

Critical Lens – In the News

In the fall of 2020, a teacher at a charter school in Texas says she was fired after wearing a mask with “Black Lives Matter” written on it (Pygas, 2020). The school told her the mask was a violation of the dress code and asked her to avoid wearing the mask due to the “current political climate.” When she stated in an email that she would not stop wearing the mask, the school said she had “effectively resigned her position,” since she did not intend to follow the established policy. Dress codes are one part of the professional behavior you may be expected to follow once you sign a teaching contract, so it is important to know exactly what your dress code policy says and what your rights are. Similar incidents have occurred in Oregon. Check out the controversy in Newberg, Oregon and how they banned freedom of expression regarding Black Lives Matter and LGBTQ rights: https://www.opb.org/article/2023/01/17/newberg-oregon-school-district-rescinds-policy-on-controversial-symbols-in-lawsuit-settlement/

Liability and Teachers

Now, imagine an elementary school teacher is outside with their students on the playground. Two children ask if they can climb on the climbing wall. The teacher agrees and begins to walk over so they can monitor their play. At that very moment, a child falls off the monkey bars she was playing on and begins to cry. The teacher quickly walks over to the fallen child and notices that she has a cut on her arm. Can this teacher be sued for negligence?

When at school, educators have a responsibility that is referred to by the courts as “in loco parentis” or “in place of parents.” This means that while in school it is the responsibility of educators to make similar judgments as it relates to the safety of children that a parent might make. Because an educator is legally responsible for the safety of children under their supervision, a teacher is considered negligent if they fail to protect a child from injury or harm.

Accidents happen, and there are multiple ways that a child could be injured, such as in the playground scenario described above, in the lab of a science classroom, or even running down the hallway. However, if it is determined that negligence did occur, or even if a parent believes that negligence took place, a liability suit can be brought against the teacher or the school. The person who was harmed can bring civil or criminal charges against the student or teacher who threatened harm. In addition, a teacher can be dismissed and lose his or her teaching license as well as be criminally or civilly charged.

Protections exist for teachers that limit liability. These include:

- A reasonable attempt was made to anticipate a dangerous condition;

- Proper precautions were instituted to include establishing rules and procedures to prevent injury;

- Students were warned of possible danger; and

- The teacher provided proper supervision (Legal Information Institute, n.d.).

The Supreme Court of Wyoming held in Fagen v. Summers (1972) that the teacher did everything possible to keep students safe following a playground accident, citing that “a teacher cannot anticipate the varied and unexpected acts which occur daily in and about the school premises.” Schools and/or teachers are generally not held responsible for accidents occurring on school property under these types of circumstances.

In another playground accident in Louisiana several years later, Partin v. Vernon Parish School Board (1977), the judge reiterated the importance of a teacher demonstrating a “high degree of care” for students under his or her supervision, while confirming the earlier decision and citing that “the teacher is not the absolute insurer of the safety of the children she supervises.” In both of these cases, the teacher was not found guilty of any negligence based on the above criteria.

Teachers can have a lawsuit brought against them for civil liability or civil statutes if it is believed that:

- a student has been mistreated or abused either verbally, physically, emotionally, or sexually by the teacher.

- a teacher discriminated against a child due to his or her gender, race, or a special need(s).

- a teacher treated certain children unfairly, such as through grading practices.

- offensive material was assigned by the teacher (Legal Information Institute, n.d.).

Once you begin teaching, your school and state will have specific policies regarding liability protection for teachers.

Critical Lens: Who Gets to Define “Offensive”?

What happens if what some families deem offensive is the lived experience of others? For example, a teacher in Texas was placed on administrative leave when some families complained about posters on the “walls” of her virtual Bitmoji classroom (Fitzsimons, 2020). These virtual “posters” depicted affirmations of LGBTQ+ communities and the Black Lives Matter Movement. But what about the students who see themselves in these LGBTQ+ and Black Lives Matter posters? How do we create classroom communities that are inclusive of various cultures and perspectives, while also acknowledging that some groups deem certain cultures and perspectives as “offensive”?

Teacher Privacy

Privacy is considered to be a protection in the U.S. Constitution under the Fourth Amendment as it relates to unreasonable searches and seizures (U.S. Constitution, Fourth Amendment).

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution ratified in 1789, revised 1992

In the Supreme Court case, O’Connor v. Ortega (1987), the court ruled that public employees retain their Fourth Amendment rights with regard to administrative searches in the workplace. The Court held that a standard of reasonableness was sufficient for work-related intrusions by public employers. It cited that an employee’s expectation of privacy may be unreasonable when the intrusion into the office is by a supervisor rather than a law enforcement official while conducting normal business functions. For teachers, the school is considered a public place and therefore there are minimal limitations placed on search and seizure. However, your personal effects, such as a phone or bag, do not belong to the workplace and if searched, require a warrant. For your own protection as a teacher, use care when deciding what to bring into the school.

Critical Lens – Teachers and Copyright Laws

A Word about Teachers and Copyright Laws

Teachers are not exempt from copyright laws, and you must be careful about the materials you use in your classroom. In the Copyright Act of 1976, Congress established guidelines for the duplication of copyrighted works. According to the law, teachers may make a single copy of a chapter of a book, an article, a short story, short essay or poem, a diagram, chart or picture. Educators may make multiple copies of copyrighted work for the use in the classroom provided they meet specific guidelines of brevity, spontaneity, and cumulative effect.

Teachers also need to be mindful of copyright laws involving electronic media. Pay attention to copyright laws for using videos, DVDs, and software programs. Be aware that internet laws are still evolving, and it is best to check with their librarian or media specialist in your school building.

Religions and Schools

The First Amendment separates religion from the business of the state. Government is prohibited from imposing religious beliefs on any person. Public school serves as a state government service and therefore it must be neutral and not promote religious beliefs on anyone in the school. The practice of religion in schools has been challenged from prayer in schools, to religion in the curriculum, religious clubs and access to public school facilities, to artifacts and clothing.

Critical Lens – Supreme Court Cases on Religion in Schools

The Supreme Court has continuously upheld the separation of religion from the school environment (ACLU Legal Bulletin, 2020).

| Year | Outcome |

| 1962 | In Engel v. Vitale, the Supreme Court upheld that nondenominational prayers were unconstitutional because they promoted religion, and schools could not officially encourage student prayer as it would interfere with the function of school. |

| 1963 | In Abington School District v. Schempp, the Supreme Court ruled that the state legislation passing a law requiring all schools to read the Bible daily was unconstitutional. |

| 1971 | In Lemon v. Kurtzman, the Supreme Court held that prayers or blessings by clergy at the opening or closing of a public ceremony in a school violates the free exercise clause. From this case there was a test that courts use to determine if religion in schools is constitutional. The questions are:

|

| 1981 | The Supreme Court ruled in Stone v. Graham that a Kentucky state law requiring the Ten Commandments be posted in school classrooms was illegal. |

The courts have upheld that there is a separation between church and state even to the extent of one’s own personal beliefs. In 1980, a teacher refused to teach a city-designed curriculum that she said violated her own religious beliefs. In the Palmer v. Board of Education of the City of Chicago (1980) decision, the court recognized that a teacher can have personal views that might be different from the curriculum, but upheld that the mandate of the school district to provide an education requires that teachers “cannot be left to teach the way they please.”

10.9 Rights of Students

Students share many of the same constitutional rights to ensure protection as adults. Several sections outlined below parallel those shown above under Teacher Rights, but with additional emphasis on the students themselves.

Courts have mandated that for a school to operate safely it needs to have broad authority to establish rules and regulations as it relates to student conduct within the school. This means that parents agree to give some level of control to schools when they enroll their child in the public school system. The courts have also insisted that students do not lose all of their constitutional rights and a school’s influence is not absolute.

Freedom of Speech and Expression

Schools have an obligation to provide a safe and orderly learning environment. Reasonable limits are put in place regarding language, such as banning offensive language, to assure appropriateness and respect. Forms of expression for students that are protected in schools include:

- the right to wear religious clothing and talk about religion,

- to be free from bullying and harassment, and

- to be free from racial or national origin discrimination (United States Courts, n.d.).

Protecting students’ rights to political speech was explored in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District (1969), which served as a landmark Supreme Court case and the decision upheld that free speech was permitted in schools. This ruling was later challenged in 1986 when a student used what was considered ‘vulgar’ language by the school in a speech at an assembly. The student was reprimanded by the school and the student sued the school claiming that his constitutional right to freedom of speech had been violated. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court where the court decided in Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986) that a school is not required to permit offensive or disruptive speech on school grounds at a school sanctioned event because offensive speech or language disrupts the educational mission of the school and is inappropriate for a school setting.

Freedom is also limited as it relates to a student newspaper. In Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988), the U.S. Supreme Court decided that a student newspaper can be regulated for “legitimate pedagogical concerns” allowing a school to remove articles that school officials deemed inappropriate for the school community. The decision went further, allowing a school to determine if the speech was written in a reasonable manner for members of the school community and ensuring that it did not contain language that was “ungrammatical, poorly written, inadequately researched, biased, prejudiced, vulgar or profane, or unsuitable for immature audiences.” The court found that because a school newspaper is not intended to have a public forum, a school can limit speech by imposing reasonable constraints if it is determined the speech would disrupt a classroom and the normal functioning of a school.

In the present day, free speech as it relates to the Internet is the same for teachers as it is for students. If it is found that the speech posted online ‘substantially disrupts’ the functioning and purpose of a school, disciplinary actions can be taken against either cohort.

Schools have the right to limit forms of expression–including speech, digital communication, and dress–when they interfere with the pedagogical mission and goals of a school.

In Doninger v. Niehoff (2008), a student’s derogatory comments posted online were found to make a substantial disruption to the school. A blog post contained language that would be prohibited within the school and was disruptive to the work and discipline of the school. A Court of Appeals held that even though the online comments were made off campus, the speech could be restricted to promote school-related goals on campus. This case relates to disruptive speech and cyberbullying. It underscores school responsibility in maintaining a safe environment for students.

The speech of students and teachers is constitutionally protected, but the extent of the speech, as it relates to the mission and goals of a school, must always have a legitimate pedagogical focus and direction. This holds true whether it is in print in a school newspaper, in the local newspaper, or in electronic format. It is true if it is part of the curriculum or in a theater production on school grounds. Speech is influenced both on and off campus and can come under the school’s authority both in-person and online.

Dress Code

Dress codes have been challenged by students claiming that they impinge on freedoms of speech and expression. Courts have upheld that school boards can impose student dress codes to include symbols, clothing, and jewelry if it is believed to have the potential to disrupt a school’s functioning.

In addition to supporting free speech as discussed above, the Tinker v. Des Moines (1969) case also weighed in regarding dress code. During the Vietnam War, students planned to wear armbands to protest the War. Their principal tried to limit these protests by banning armbands. The court ruled against the school, holding that there was no evidence that students wearing armbands would disrupt school functioning.

In 2006, a student wore a shirt to school that other students found offensive and which depicted a particular political viewpoint. He was asked to cover the shirt based on the off-putting image and speech. He refused and was given a disciplinary referral. In Guiles v. Marineau (2006), the student then sued the school administrators to have the disciplinary referral expunged from his record and to disallow the school from enforcing the dress code policy against him. The District court held that the school was entitled to enforce its dress code policy, but upon appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that the shirt was protected speech under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

In another case, B.H. and K.M. v. Easton Area School District (2013), students were suspended for wearing bracelets that showed support for breast cancer awareness. In this case, the judge ruled in favor of the students. The school district then elevated the case to the Supreme Court, but the court refused to hear the case, stating that the message on the bracelet did not use lewd language and was not disruptive to the purpose of education. The First Amendment requires schools to see all student views equally, as long as they are not obscene or disruptive, irrespective of the message expressed (Sherwin, 2017).

Pause and Ponder – Dress Code

Andrew Johnson, a high school wrestler in New Jersey who wore his hair in cheekbone-length dreadlocks. Moments before Johnson was about to go to the mat for a match, the referee told him he wouldn’t be allowed to compete because his hair was too long.

Do you think this was an ethical decision?

What are the equity implications ion this?

Video 10.7

The purpose of a dress code is to provide an optimal learning environment. However, the learning environment can be restrictive if it includes gender-biased language that results in stricter enforcement of rules for female minority students and groups belonging to a particular culture. A gender-neutral dress code is recommended, and those who create the policy should attempt to gather student input when revising the school dress code. (Barrett, 2018).

Critical Lens – In the News

Pay attention to the news–you are likely to hear many examples of dress code violations that systematically oppress certain groups. For example, a school in Houston made the news in early 2020[2] for their dress code policy. The policy required male students to keep their hair “ear-length or shorter,” thus banning dreadlocks. One male student, De’Andre Arnold was told he would have to cut his dreadlocks in order to walk at graduation. Despite complaints, the school district stood by its policy. In August, a federal court ruled this policy was discriminatory.

The American Civil Liberties Union also provides guidance on student rights as they relate to school dress codes, gender, and self-expression:

- Views are protected by the First Amendment and therefore schools cannot ban symbols or slogans or messages that they disagree with on student shirts, buttons, wristbands, or other garments or accessories.

- While public schools can establish dress codes, they cannot treat boys and girls differently, censor viewpoints, or force students to conform to gender stereotypes under federal law.

- Students are allowed to wear clothing that aligns with their gender identity and expression (ACLU Fact Sheet, 2016).

Schools and administrators must be aware of the constitutional rights of students and protect these freedoms. Schools can assert certain restrictions as they relate to freedom of speech and expression, but at the same time they also need to be cognizant of student diversity and cultural differences, as well as gender distinctions, and economic disparities.

Activity

Think about some of your experiences with dress codes. Which cultures were normalized, and which were marginalized? Here are a few ideas to get you started.

- Gender and sexuality: Were males and females held to different standards? (For example, were females expected to wear skirts or not to wear strappy shirts? See the #Iamnotadistraction movement[3] or the Let Her Learn report[4] advocating for female bodies not to be hyper-regulated and sexualized in dress codes.)

- Race: Were certain hairstyles or traditions allowed or not? (For example, Black hair styles[5] are frequently at risk of marginalization, along with Black and Brown bodies in general[6].) Or, are certain racial groups punished more frequently[7] for dress code violations?

- Religion: Are head coverings and facial hair regulated? (For example, the Air Force updated their policy[8] in February 2020.)

- Socioeconomic: Were certain types of clothing allowed or not? (For example, some dress codes limit cheap plastic flip flops but allow more expensive leather ones.)

Search and Seizure

Imagine that a teacher suspects a student has illegal drugs in her backpack. They noticed the student at her locker placing a small bag in the front pocket. The teacher immediately reports their suspicions to the principal. What should be the next step? The school administrator must have a “reasonable suspicion” based on facts specific to the student or the situation. A “hunch” is not sufficient. Rather, the principal must believe that searching the student will turn up evidence of violating a school rule or law. “Reasonable” is based on what is being searched for and the age of the student.

The Fourth Amendment of the Constitution protects U.S. citizens from unlawful search and seizure of possessions. If there is probable cause for a search, a warrant is required from the court system before a person can be searched. Because of the nature and purpose of school, courts have allowed schools to both search and seize possessions if there is probable cause.

Personal materials, including lockers, are not supposed to be searched without reasonable suspicion that a student is in violation of the law or a school rule.

In New Jersey v. T.L.O. (1985), the Supreme Court established a standard of reasonableness for student searches conducted at school and by public school personnel. While the Fourth Amendment disallowing unreasonable search and seizure still applies, if school administrators have a reasonable suspicion that a student has either broken the law or violated a school rule, the search is justified. In this case, the student was found smoking in the bathroom, a violation of school rules, and taken to the principal’s office where her purse was searched based on a reasonable assumption that the student had cigarettes in her purse.

Random drug tests have historically been permissible for both teachers and students. In the Supreme Court case Board of Education of Independent School District No. 92 of Pottawatomie County v. Earls (2002), the court held that athletes can be randomly tested for drugs to protect the safety of the school and to ensure a drug-free school. The safety and well-being of the school outweighed the privacy rights of students who were voluntarily participating in the sporting events. The Court concluded that while the students participating in extracurricular activities have limited Fourth Amendment rights, within the school setting there is a lesser expectation of privacy, and the students’ rights must be balanced against the school’s interest in keeping illegal drug use to a minimum (Staros & Williams, 2007).

In 2005, a 13-year old student was called out of class and questioned by police officers with school officials present regarding neighborhood burglaries. His parents were not contacted, nor was he read his Miranda rights, such as the right to remain silent, leave the room, or have access to a lawyer. The child confessed to the crime but later sought to suppress his confession based on not receiving any indications of his rights while he was in police custody in the school conference room. This case, J.D.B. v. North Carolina (2011), was later heard by the Supreme Court where they ruled that age should have been considered in deciding whether the student was in police custody within the school grounds. The justices went on to state that there are psychological differences between an adult and a child, and when police are involved in questioning students, they must use “common sense” due to the developmental differences of children. The Miranda warnings should have been applied in this case in a manner appropriate for the student prior to his questioning.

Search has also been controversial with the use of video surveillance and metal detectors in schools. Currently, courts have held that if school safety has been threatened, means of surveillance can be introduced into the school, but that extensive surveillance using video or metal detectors can hinder reasonableness of the surveillance and violate Fourth Amendment protections. The intent of school policies and procedures are consistently to provide and maintain “a safe, secure, healthy, and disruption-free learning environment” that is conducive and supportive to teaching and learning (Vacca, 2014, p. 5).

Privacy of Records

In 1974, Congress passed the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), also called the Buckley Amendment. This was an Amendment to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965. FERPA is a federal law that protects the privacy of student educational records. FERPA requires schools to allow parents and students access to official school records. It also requires schools to provide procedures for parents to challenge the accuracy or completeness of information in their child’s record. Parents retain the rights of access to their child’s school record until the child reaches the age of eighteen or is enrolled in a postsecondary institution.

The intent of FERPA is to protect student privacy and improve parental access to their child’s information within the school. It does not guarantee access to all school records on a child, such as personal teacher notes, letters of reference, grade books, or correspondence with a principal. These items are exempted from view. There may also be files or information that are kept separate from a student’s file to protect the privacy rights of other students in the school.

FERPA guidelines require schools to:

- Inform parents annually of their rights regarding their child’s records.

- Provide parents access to their child’s records.

- Maintain procedures that allow parents to challenge and if needed, amend inaccurate information.

- Protect parents from disclosure of confidential information to third parties without their consent (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, 1974).

- Allow students to opt out of testing

Deeper Dive – FERPA

What is FERPA?

This brief yet comprehensive video will outline what the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act is and how it impacts students both at the K-12 and higher education levels.

Video Link: What is FERPA? Student Privacy 101

Have more questions about the role of FERPA in educational settings?

- United States Department of Education: Protecting Student Privacy: Frequently Asked Questions

- United States Department of Education: Protecting Student Privacy: K-12 School Officials

10. 10 Current Implications

Throughout the history of schools in the United States, ethics and the function of laws have evolved as society has changed. To date, current issues continue to be addressed in our nation’s public schools and within our court systems. While others exist as well, below are three current issues within education and society as a whole.

Racial Issues

Today, racial concerns remain a key issue for schools and society at large. In T.B. et al. v. Independent School District 112 (2019), African American students filed a complaint against white students in Minnesota. They claimed they had been harassed and the school did not intervene to remove racism, harassment, and discrimination nor did it protect their rights to safe and equal access to education within the school environment. This is required as part of the Equal Protection Clause under the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. As of this writing, the case remains open in the court of appeals.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 states, “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance” (Civil Rights Act, 1964).

Racial harassment continues to occur in schools to the present day. As a teacher, you are responsible for enforcing policies and procedures that are appropriate within the classroom to maintain a safe environment for all students. Immediate action is required to respond to bullying and intimidation, such as speaking up and talking with the offending students and reporting the action to your principal when you hear or see questionable behavior or actions within your school. Regular professional development and training can additionally help inform and support teachers. A culture of inclusion and acceptance is required by school leadership that permeates throughout the school and community.

LGBTQ+ Rights and Discrimination

V

Video 10.8