8 Assessment

“Mistakes are necessary for any learning to happen, and yet traditional grading treats mistakes as unwanted, unhelpful, and deserving of penalty.”

Joe Feldman

Learning Objectives

- Identify some of the the historical factors that influence contemporary ideas about assessment

- Describe and critique the usefulness of Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Differentiate and describe forms of assessment and issues associated with grading

- Describe how grading practices can lead to more equitable outcomes

What is the purpose of assessment in schools? At the core, the purpose is to assess student learning, progress, and understanding to ensure that the teaching is appropriate and ultimately, successful. It provides valuable information to teachers about their students’ knowledge and abilities, as well as their own instructional methods. It involves gathering information about students’ knowledge, skills, and abilities to inform instructional practices and enhance educational outcomes. For external stakeholders such as school boards, administrators, parents, there is an accountability mandate to ensure that students are receiving a high-quality education. Assessment is also tied to grading and performance, and has huge implications for students in terms of academic and professional goals. For many years, grading practices were accepted and not questioned. Recently and increasingly, grading and testing are being examined for fairness, appropriateness and equity. There is a growing recognition about the role of equitable grading and testing in creating a more just society.

8.1 Historical Context

Historically, unfair and discriminatory bias in assessment practices have been perpetuated over time, stemming from cultural, social, or systemic biases. The US educational system is still functioning within the legacy of these influences; learning assessment is naturally shaped by the same factors. These biases disproportionately disadvantage certain groups of individuals based due to issues such as race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, or cultural background. Because educational assessments have often reflected the dominant cultural norms and values of the society in which they were created, this has led to unequal opportunities and outcomes for marginalized groups.

Language barriers, biased questions and culturally unfamiliar content, for example, have unfairly disadvantaged students from non-dominant backgrounds. Addressing historical bias requires a critical examination of assessment tools, content, and methodologies to ensure they are inclusive, culturally sensitive, and reflecting diverse perspectives. By acknowledging and rectifying historical bias in assessment, educational institutions can strive for greater equity and provide a more accurate reflection of students’ true capabilities and potential. What follows are just a couple of historical examples which shaped and influenced how educators assessed and tested students in US schools.

The Eugenics Movement: Intelligence Testing and Categorization

In the US, in order to justify the practice of enslavement of human beings, a type of racism emerged in the 1800’s called scientific racism. Scientific racism attempted to justify the superiority of the white race by relying on pseudoscience. One way scientific racism manifested was in the Eugenics movement. Eugenics is a set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Eugenics became an academic discipline at many colleges and universities and received funding from many sources.

With the introduction of genetics, Eugenics became associated with genetic determinism, the belief that human character is entirely or in the majority caused by genes, unaffected by education or living conditions. Organizations were formed to win public support and sway opinion towards Eugenic values. At the beginning of the 1900’s, educational academics were exploring ideas around “natural and genetically based” intelligence. They brought all their preconceived notions about racial and ethnic superiority to their explorations and devised intelligence tests that ended up often creating self-fulfilling prophecies. The legacy of this built-in systemic bias and implied White superiority live on today through IQ testing and standardized tests – up to and including college entrance exams.

Video 8.1

Sputnik: Cold War Fears

The headlines on October 4, 1957 revealed that the Soviet Union had successfully launched Sputnik 1, the first man-made satellite. This event single-handedly launched America into a decades long endeavor to not only compete in the space program, but to evaluate and launch a new and purportedly improved educational system that would afford its students a curriculum of rigor, especially in the realms of mathematics and science. It would, presumably, prepare U.S. students to compete with other nations.

This event also marked a pivotal reversal of progressive educational philosophy that prevailed during the 1950’s. Some proponents of a more rigorous curricula contended that U.S. education was “soft,” that they relied too heavily on vocational training, and that teachers were not trained effectively. (Watters, 2015) Critics of the U.S. educational system included Arthur Bestor (Educational Wastelands 1953 and Restoration of Learning 1956). Bestor, professor of history at the University of Illinois wrote a Life magazine article, “What Went Wrong with US Schools?” He made sharp comparisons to schools and the Sputnik satellite, contending that US students were simply not prepared. (Bestor, 1953)

These series of events set the stage for the educational reform measures of the next few decades in US public schools, a period marked by the need for rigor, accountability and competitive edge within the global sphere. Nearly two decades later, the historic report, A Nation at Risk (April 1983), would catapult a nation toward an increased urgency for rigor and competency. There was a sense that our very future as a world power hinged upon the success of our schools. Critics of progressive education, in particular, took aim at the US public school system. Their fears would cause a significant shift in the approach to US schools, bringing business and governmental leaders to the table for the next few decades with heightened expectations for assessing the progress of children in US schools.

Critical Lens – A Nation at Risk

We report to the American people that while we can take justifiable pride in what our schools and colleges have historically accomplished and contributed to the United States and the well- being of its people, the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people. – National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983

The emerging emphasis was on summative assessment in the form of increased standardized testing, and stakes became quite high in terms of their consequences for schools, communities and students. As US American students falter compared to other industrialized countries, policy makers have shifted toward a great concentration on high-stakes testing to increase student standing. Unfortunately, this emphasis on high-stakes testing has not yielded an increase in scores (Michael Hout, 2012).

8.2 Global Assessment

According to the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), Reading Literacy scores, United States students earned an average score of 497, while students in Singapore earned the highest average, 535 and students in Lebanon tied with students in Kosovo for the lowest average of 347. This places United States students in the average range of reading. (Reading Literacy: Average Scores, 2015)

Mathematics Literacy scores revealed an average of 470 for U.S. students as compared to Singapore scores of 564 at the highest end and 328 from the Dominican Republic at the lowest end placing United States students as below average performers. (Mathematics Literacy: Average Scores, 2015)

Although students in the United States have demonstrated an interest and positive attitude toward science, the scores reveal a discrepancy between attitude and performance, with United States students scoring at an average of 496 as compared to a high of 556 (Singapore), and a low of Dominican Republic (332).

8.3 High Stakes Testing and Accountability

High stakes testing is often used as a tool to hold schools and teachers accountable for student learning. It may even be viewed as the sole measure of student success. If student learning is measured through tests, then we must take into account the issue of bias particularly in standardized testing. Although most forms of assessment have some kind of implicit bias, standardized testing is rife with it (Couch et al., 2021, Taylor and Bobbit Nolan 2022.)

Pause and Ponder – Article from National Education Association

High-stakes testing has always been supported by both major political parties in the United States, and in 2002 the U.S. government passed the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) into law (United States Congress, 2002). As a policy, NCLB relies upon high-stakes testing as the central mechanism for school reform, mandating that all students be tested in reading and math in grades 3-8 and once in high school, with future provisions that students be tested at least once at the elementary, middle, and high school levels in science. If schools do not show consistent growth on these tests in subgroups related to race, economic class, special education, and English language proficiency, among others, they face sanctions such as a loss of federal funding, with the ultimate policy goal of all students reaching 100% proficiency by 2014 (Karp, 2006). In 2015, Every Student Succeeds Act was passed. ESSA takes steps to reduce standardized testing.

Video 8.2

Accountability (holding teachers, schools, and districts responsible, or accountable, for increasing student learning and performance) carries both benefits and challenges. Of course, all educators and educational stakeholders share a common goal of advancing student learning. Testing provides an opportunity to understand what students have learned. They provide a common framework to measure students across age levels and geographic regions. However, accountability can be hard to measure, and sometimes standardized test scores become the primary way to measure teacher effectiveness. This measurement can be unfair, especially when we consider the varying resources allocated to schools, the cultural bias of standardized testing, and the reality that some students are not good test takers.

In an age of accountability and data driven curriculum, policy makers have supported standardized and other testing measures; however, some organizations have highlighted the importance of a balance between teaching and testing. The “Learning Is More Than a Test Score” campaign has brought to light the curricula omissions in favor of increased time for testing and preparation of testing. Studies reveal that students spend 20 to 50 hours each year taking tests while those in heavily tested grades spend 60 to more than 110 hours per year. These figures translate to additional pupil expenditures of $700 to at time, more than $1,000 per year and account for 20 to 40 minutes of lost instructional time each day (see footnote 1). The debate continues about the loss of academic time and dollars spent in relation to the benefits of test preparation in schools across the nation.

8.4 Types of Assessment

If used correctly, assessment is an integral part of the teaching/learning process. For teachers, it drives their instructions and for students, it drives their learning. If done well, the feedback that educators provide to students will guide them on how to achieve their goals. In this section, we are going to focus on different types of assessment.

Critical Lens – 14 Top Ways to Assess Students in Education

Video 8.3

Diagnostic Assessment

The diagnostic assessment is a form of pre-assesment where teachers can learn about students’ strengths, weaknesses, knowledge and skills before their instruction. This type of assessment is not usually graded as it is a baseline for teachers to know where to start in their lessons. With this form of assessment, teachers can plan meaningful and efficient instruction and can provide students with an individualized learning experience.

Formative Assessment

The formative assessment is one which occurs throughout a lesson or unit and may take a variety of forms. A teacher may determine what students know by question and answer formats, checklists, or by paper and pencil assignments. Likewise, games such as Kahoot and Jeopardy may assist in similar data collection. The informed teacher can utilize the results of the formative assessment to re-engage or to modify the teaching plans to meet the individual needs of the students. Formative assessments are typically lower stress than summative assessments; often students are not even aware their teachers are using the activity to assess their learning.

Summative Assessment

The summative assessment is the evaluation that is given at the conclusion of a unit or lesson. It may determine student placement or level of knowledge and is often thought of as a grade determinant. Results of summative assessment are not used in lesson planning; rather, they are used to evaluate the mastery of material. It can take the form of a question and answer or paper and pencil approach like the formative assessment. Summative assessments also typically have one correct answer.

| Formative Assessment | Both | Summative Assessment |

| They are assessments that we carry out to help inform the learning ‘in the moment’. Formative assessment is continuous, informal and should have a central and pivotal role in every classroom.

If used correctly, it will have a high impact on current learning and help you guide your instruction and teaching |

Are ways to assess pupils.

|

There are different types of summative assessments that we carry out ‘after the event,’ often periodic (rather than continuous), and are often measured against a set standard.

Summative assessment can be thought of as helping to validate and ‘check’ formative assessment – it is a periodic measure of how children are, overall, progressing in their mathematics learning. |

Includes:

|

Includes:

|

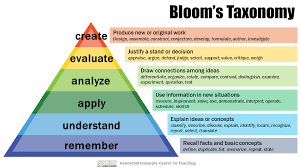

8.5 Bloom’s Taxonomy

Teaching is a complex endeavor and many tools have been developed to organize instruction and ensure lessons are purposeful and lead all students to learn. Bloom’s Taxonomy has been used to both design instruction and assess learning for decades in the United States. The intent is to promote critical thinking and encourage educators to plan for the level of critical thinking. It provides a road map for teachers in terms of the level of complexity as it relates to the subject being studied. Do we want students to be able to answer questions on a test about the Civil War or produce a play with fellow students about the Civil War? Teachers need to define the level of complexity and then assess for that specifically. Once educators assess the learning, they subsequently can redesign the instructional approach. In this way, assessment and instructional design are involved in a symbiotic, organic and iterative process with each other. Effective instruction is dependent on ongoing assessment.

Bloom’s Taxonomy was created by Benjamin Bloom in 1956 at the University of Chicago. This taxonomy is a classification system which has helped educators to both design curriculum and plan assessment.

Bloom’s Taxonomy represents a process of thinking. The first level of questioning prompts the learner to remember facts about a given concept such as when did the Brown vs Board of Education case get decided? Students would recall the year 1954. The next levels require the connection of these facts to develop a deeper understanding of their meaning, such as what did the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling actually mean for US Americans? On the highest level, students must create a new idea or demonstrate their understanding. Bloom’s Taxonomy is also used to formulate learning outcomes and drive assessment.

Video 8.4

Bloom’s hierarchical classification of thinking has been used for classroom instruction for decades. It relies on a continuum of cognitive complexity from simple to complex and concrete to abstract (Armstrong, 2010). It is a commonly-used resource for writing objectives with verbs classified by level. The verbs at the top of the pyramid (figure 8.5) are believed to represent higher-order thinking skills while the ones at the bottom are more basic.

Bloom’s taxonomy underwent a major revision by Krathwohl & Anderson (2001). The image above shows the increasing cognitive load and provides a short definition of each level. The verbs associated with differing levels of thinking skills required for any given task provide guidance as a teacher writes outcomes for any lesson for a class. For instance, a lower order outcome may be: The student will recall multiplication tables one through four. A higher order outcome might be: The student will differentiate between nutritious foods and foods with processed ingredients. When teachers understand the complexity of thinking levels required by the lesson, they may ensure that students have a good balance among all skills in the spectrum.

Focusing on what students should know is frequently called the “cognitive” approach; focusing on what students should be able to do is known as the “behavioral” approach. Most teachers often combine the two and include both declarative and procedural knowledge within their objectives. Large-scale learning objectives will be articulated in a teacher’s curriculum guide, but it is up to each individual teacher to formulate learning objectives for individual lesson plans.

Designing and administering assessments that align with your standards and engage students at various levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy is an important first step, but another key part of effective assessments is analyzing the data you collect. Analysis of data can occur on individual student, small group, or whole class levels. If many students demonstrate a similar misunderstanding on an assessment, that data indicates the teacher should re-teach that content to increase students’ mastery. Data-driven instruction looks at the results of various assessments when considering next instructional steps. Assessment and grades are not the same. Grades can be a form of assessment, but not all assessments are graded. Assessments can include both quantitative and qualitative data. For example, observing students during an activity would not be a grade, but it would give you important information about what a student does or does not understand. There are many practices that exist to support students during assessments, such as IEP accommodations, differentiated assessments, retakes, and no-zero policies.

8.6 Grading

Grading involves assigning scores or labels–such as letter grades, rubric scores, complete or incomplete labels, or numeric values–to a student’s performance on a task. Two forms of grading that you may have experienced in school include mastery grading and standards-based grading. Mastery grading means to structure courses in a way that allows students the time and flexibility to focus on mastering a standard rather than achieving a certain number or letter grade. Standards-based grading breaks down the subject matter into smaller “learning targets.” Each target (often phrased as an “I can” statement) is a teachable concept that students should master by the end of the course. Throughout the term, student learning on each target is recorded (Common Goal Systems, 2021). For example, in a simple grade on a report card, it may say the student received an A, or a percentage, such as 96%. In a standards-based report card, each target is broken down, such as “I can solve number sentences that have brackets”, with a score of 1-4; then, “I can find the sum of two-digit numbers”, with a score of 1-4. In this scale, 1 indicates little or no mastery and 4 indicates advanced mastery. Teachers track student progress, give appropriate feedback, and adapt instruction to meet student needs.

The issue of grading is complex and often confusing for new teachers. There may be department-, school-, or district-wide rules about how many grades a teacher should have in a quarter or semester. Some parents and students are very focused on high grades, even if they don’t reflect the student’s actual level of understanding. Most would argue that the primary purpose of the grading system is to clearly, accurately, consistently, and fairly communicate learning progress and achievement to students, families, postsecondary institutions, and prospective employers (Great Schools Partnerships, 2021); if teachers do not provide timely and meaningful feedback, however, grading can sometimes interfere with assessments of students’ actual understanding.

Grading for Equity

In an ideal world, grades and assessments are fair and impartial. However, the reality is that bias often creeps into assessment systems. One simple work-around is to use rubrics with specific criteria. David M Quinn (2021) conducted an experiment in which he gave teachers two second grade writing samples, one presented as a Black student’s work and one as a White student’s. Teachers gave the White student higher scores except when they used a grading rubric with specific criteria, which caused the pre-existing racial bias in the scores to disappear. Therefore, rubrics not only help students know up front what expectations are for an assignment, but also reduce opportunities for bias to impact grading. See article below.

Pause and Ponder – How to Reduce Racial Bias in Grading by David M. Quinn

Through his work as a teacher and administrator, Joe Feldman is a leading advocate for more equitable grading. He points out that students have to navigate very different grading systems in each of their classrooms, and it may not always lead to equitable grading despite the best intentions of their teachers. Educators tend to base their grading on participation, homework and timeliness. While educators do not consciously set up inequitable grading processes, these grading systems are often unexamined and result in negative and long-lasting consequences for students.

Critical Lens – Call to Action for Equitable Grading Practices

Feldman describes the basis of the problem:

- grading practices vary from teacher to teacher, and are largely subjective

- Grades provide unclear and often misleading information to parents, students, and postsecondary institutions

- Traditional grading practices are often corrupted by implicit racial, class, and gender biases

- Most teachers use grading practices that use mathematically unsound calculations that depress student achievement and progress.

Video 8.5

Pause and Ponder – Educator Quote

“Examining my own grading practice challenges what I’ve learned to do as a teacher in terms of what I think students need to know, what they need to show back to me, and how to grade them. This feels really important, messy, and really uncomfortable. It is ‘Oh my gosh, look what I’ve been doing!’ I don’t blame myself because I didn’t know any better. I did what was done to me. But now I’m in a place that I feel really strongly that I can’t do that anymore. I can’t use grading as a way to discipline kids anymore. I look at what I have been doing, and I have to do things differently”- Call to Action For Equitable Grading, 2018

Feldman’s Recommendations for Equitable Grading:

- Practices that are mathematically sound: Using algorithms that conform to sound mathematical principles and reflect growth and learning as well as truly describe a student’s level of mastery. Examples: Using a 0-4 instead of a 0-100 point scale; avoiding giving students scores of zero; and weighing more recent performance and growth instead of averaging performance over time.

- Practices that value knowledge, not environment or behavior. Evaluating students only on their level of content mastery, not how they act (or how teachers perceive or interpret their behavior). Examples: Not grading subjectively interpreted behaviors such as a student’s “effort” or “participation”, or on completion of homework; focusing grades on required content or standards, not extra credit or when work is turned in; not using grades to control students or reward compliance; and providing alternative consequences for cheating or missed assignments.

- Practices that support hope and a growth mindset: Encouraging mistakes as part of the learning process and building students’ persistence and resilience. Examples: Allowing test/project retakes to emphasize and reward learning rather than penalize it; and replacing previous scores with current scores.

- Practices that “lift the veil” on how to succeed: Making grades simpler to understand and more transparent. Examples: Creating effective, standards-aligned rubrics; using simplified grade calculations and standards-based scales and gradebooks.

- Practices that build soft skills without including them in the grade: Supporting students’ intrinsic motivation and confidence rather than relying on an extrinsic point system. Examples: Using peer/self-evaluation and reflection; using a more expansive range of feedback strategies; building self-regulation.

- Improved grading practices are accurate, bias-resistant, and motivate students in ways traditional grading does not,

Conclusion

As you can see, the stroke of a pen can have lasting impressions on the student. Grades can classify learners. They can motivate or squelch desire. They can encourage or demean. They can be used to punish or to teach. It is critical for educators to recognize that grades have long lasting consequences on the lives of your students.

Activity – Questions to Consider

- Have you examined your own experiences with assessment (testing and grading) and what impact they have had so far in your own life?

- Have you reflected on how your own biases may shape your assessment strategies in the future?

- How will you communicate about assessment to future students?

- How will all of this impact how you plan curricula and evaluate student learning to benefit all learners equitably?

References

Active learning. Active Learning | Center for Educational Innovation. (n.d.). https://cei.umn.edu/teaching-resources/active-learning

Allen, Garland E. (2004). “Was Nazi eugenics created in the US?”. EMBO Reports. 5 (5): 451–452. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400158. PMC 1299061.

Bosworth, Dee Ann. “American Indian Boarding Schools: An Exploration of Global, Ethnic & Cultural Cleansing” (PDF). www.sagchip.org. Mount Pleasant, Michigan:

Couch, M., Frost, M., Santiago, J., & Hilton, A. (2021). Rethinking Standardized Testing From An Access, Equity And Achievement Perspective: Has Anything Changed For African American Students? Journal of Research Initiatives, 5(3). https://digitalcommons.uncfsu.edu/jri/vol5/iss3/6/

Elsesser, K. (2019, December 11). Lawsuit claims sat and act are biased-here’s what research says. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kimelsesser/2019/12/11/lawsuit-claims-sat-and-act-are-biased-heres-what-research-says/?sh=5d0af5583c42

Feldman, Joel. (2019) Grading for Equity. Corwin

Galton, Francis (1904). “Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope, and Aims”. The American Journal of Sociology. X (1): 82. Bibcode:1904Natur..70…82.. doi:10.1038/070082a0. Archived from the original on 1 March 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

Guzmán, Gonzalo (November 2021). “”Things change you know”: Schools as the Architects of the Mexican Race in Depression-Era Wyoming”. History of Education Quarterly. 61 (4): 392–422. doi:10.1017/heq.2021.37. ISSN 0018-2680. S2CID 240357463.

Hood, Stafford, et al. Race and Culturally Responsive Inquiry in Education : Improving Research, Evaluation, and Assessment. Edited by Stafford Hood et al., Harvard Education Press, 2022.

“Eugenics”. Unified Medical Language System (Psychological Index Terms). Bethesda, Maryland: National Library of Medicine. 2009. Archived from the original on 16 October 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) | U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). https://www.ed.gov/essa?src=rn

Hurford, Donna, and Andrew Read. Bias-Aware Teaching, Learning and Assessment. 1st ed., Critical Publishing, 2022.

Jennifer Jones, Dee Ann Bosworth, Amy Lonetree, “American Indian Boarding Schools: An Exploration of Global Ethnic & Cultural Cleansing”, Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture & Lifeways, 2011, accessed 25 January 2014

Milner, H. R. (2012). Beyond a Test Score: Explaining Opportunity Gaps in Educational Practice. Journal of Black Studies, 43(6), 693–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934712442539

Nelson-Barber, S., & Trumbull, E. (2007). Making assessment practices valid for Indigenous American students. Journal of American Indian Education, 132-147.

Opinion | The quiet resegregation of America constitutes a national crisis”. NBC News. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

Phelps, R. (2006). Measuring Intelligence: Facts and Fallacies. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 27(4), 356. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200608000-00012

Richmond, Emily (June 11, 2012). “Schools Are More Segregated Today Than During the Late 1960s”. The Atlantic. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

Schwartz, K. (2019, February 10). How teachers are changing grading practices with an eye on equity. KQED. https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/52813/how-teachers-are-changing-grading-practices-with-an-eye-on-equity

Taylor, Catherine S., and Susan Bobbitt Nolen. Culturally and Socially Responsible Assessment : Theory, Research, and Practice. Teachers College Press, 2022.

The Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture & Lifeways. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

Using Bloom’s taxonomy to write effective learning outcomes. Teaching Innovation and Pedagogical Support. (2022, July 26). https://tips.uark.edu/using-blooms-taxonomy/

Wells, M., & Clayton, C. (n.d.). Chapter 6: Curriculum: Planning, assessment, & instruction. Foundations of American Education: A Critical Lens. https://viva.pressbooks.pub/foundationsofamericaneducation/chapter/chapter-6/

Ziibiwing- Home Page. (n.d.). Www.sagchip.org. http://www.sagchip.org/ziibiwing/

Images

8.1 – “Safavid-star” by wikimedia comons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

8.2 “You a Mathematician or Nah? Solidifying Black Boy Brilliance Through Culturally Responsive Mathematics Instruction” by Heineman Blog

8.3 “Frontispiece and title page of “Eugenics” | Andrew Kuchling | “ by Andrew Kuchling is licensed under CC BY 4.0

8.4 “HD wallpaper: Human Knowledge Shows Understanding Education And Global, comprehension | Wallpaper Flare” is in the Public Domain, CC0

8.5 “File:Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy.jpg – Wikimedia Commons” is in the Public Domain, CC0

8.6 “School Report Card – Openclipart” is in the Public Domain, CC0

8.7 “school, learn, students, forward, children, young people, positive, hope, board, write | Pxfuel” is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Videos

8.1 “The dark history of IQ tests – Stefan C. Dombrowski” by Stefan C. Dombrowski is in the Public Domain, CC0

8.2 “Should we get rid of standardized testing? – Arlo Kempf” by Arlo Kempf is in the Public Domain, CC0

8.3 “Assessment in Education: Top 14 Examples” by Frank Arela is in the Public Domain, CC0

8.4 “Use Bloom’s to Think Critically” by LSU Center for Academic Success is in the Public Domain, CC0

8.5 “Grading for Equity: What It Is, Why It Matters, How It Transforms Schools and Classrooms” by National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) is in the Public Domain, CC0