2 History of US Education

“The central role that slavery played in the development of the United States is beyond dispute. And yet, we the people do not like to talk about slavery, or even think about it, much less teach it or learn it. The implications of doing so unnerve us. If the cornerstone of the Confederacy was slavery, then what does that say about those who revere the people who took up arms to keep African Americans in chains? If James Madison, the principal architect of the Constitution, could hold people in bondage his entire life, refusing to free a single soul even upon his death, then what does that say about our nation’s founders? About our nation itself? Slavery is hard history. It is hard to comprehend the inhumanity that defined it. It is hard to discuss the violence that sustained it. It is hard to teach the ideology of white supremacy that justified it. And it is hard to learn about those who abided it.”

Hasan Kwame Jeffries – “Teaching Hard History” by SPLC

Learning Objectives

- Examine events, legislation, and people who shaped the US school system.

- Highlight the contributions of certain individuals whose work impacted the development of US schools in equitable and inequitable ways.

- Demonstrate how schools have always reflected historical and cultural realities of the times such as systemic racism, white supremacy, genocide, classism, and sexism.

- Analyze how systems of oppression in US schooling serve to perpetuate such inequality.

“Out of slavery — and the anti-black racism it required — grew nearly everything that has truly made America exceptional: its economic might, its industrial power, its electoral system, diet and popular music, the inequities of its public health and education, its astonishing penchant for violence, its income inequality, the example it sets for the world as a land of freedom and equality, its slang, its legal system and the endemic racial fears and hatreds that continue to plague it to this day. The seeds of all that were planted long before our official birth date, in 1776, when the men known as our founders formally declared independence from Britain.” The 1619 Project

Pause and Ponder – Questions to Consider

- Why is it so difficult for educators to address the topic of slavery and racism?

- Why do you think we are starting a chapter on the history of education in the United States with the topic of slavery?

- Is this just about Black people or a legacy of systems of power and oppressions which impacted communities of color?

- How does such oppression persist today, and how should educators proceed?

- What responsibilities do educators have to disrupt systems of oppression?

What does the history of education have to do with that hard history referenced in the above quotes? The history of US education is inseparable from the history of nation-building, so we begin this chapter with this important framing. Because race is such a polarizing force in our nation today, we choose to focus on slavery as a way to frame the difficulty of teaching about history in the US. In this section, we will follow historical events through key periods of U.S history and identify the forces that left lasting influences on education in the United States.

“In the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, the Founding Fathers enumerated the lofty goals of their radical experiment in democracy; racial justice, however, was not included in that list. Instead, they embedded protections for slavery and the transatlantic slave trade into the founding document, guaranteeing inequality for generations to come. To achieve the noble aims of the nation’s architects, we the people have to eliminate racial injustice in the present. But we cannot do that until we come to terms with racial injustice in our past, beginning with slavery. (Hasan Kwame Jeffries https://www.splcenter.org/20180131/teaching-hard-history)

So much of the historical narrative has centered on the achievement and influence of the white men who had the power to control the narrative. The New York Times 1619 project attempts to reframe this history, beginning by identifying this nation’s birth as the moment in 1619 when the first ship carrying slaves arrived in the British colony of Virginia (rather than July 4th, 1776) because chattel slavery served as a foundation of this nation’s economic and political systems for the next 250 years.

Deeper Dive – 1619 Project and Black History timeline

Check out the 1619 Project

Check out the Black History Timeline

The history of education in the US naturally reflects the history of the nation. The schools have typically taught students that slavery ended in the 19th century, a stance that disregards the formal and informal barriers that were created and maintained for another hundred years (and beyond). Following the Civil War, Jim Crow laws explicitly created separate systems for people of color, which were strictly maintained in structures such as schooling, healthcare, and the justice system and had far-reaching consequences across the generations, causing a significant wealth gap that persists to this day . When Jim Crow ended, these systems were embedded throughout society and served to disenfranchise communities of color in order to uphold and support white power structures (such as where people could live, work and go to school). While understanding the legacy of slavery is central to understanding our history in this country, racialized oppression impacted other oppressed peoples, notably the people who lived here first, the indigenous people of North America. Westward expansion, Christian missionaries, and the spread of disease brought destruction and genocide to native communities, their languages, cultural practices, and customs. More on these topics will be covered later in this chapter.

Our educational system has been centered around narratives of meritocracy and equality, those precious American ideals that suggest that if any person merely works hard enough, they can have access to the American dream. It is not typically taught that slavery was the economic engine that fueled the birth of this nation, nor that specific laws and policies maintained those inequalities through to the modern day. This lack of reflection on slavery’s role in our collective history has been damaging because as a nation, we are now divided around these issues. Many in the US society struggle to understand the lived experiences of BIPOC communities because they do not match the stories with which they were raised, particularly the myths of meritocracy and equality.

Teachers who address slavery in the classroom must consider how they can empower students to process hard history. Author and educator Adrienne Stang and Harvard researcher Danielle Allen discussed the importance of beginning the lesson with affirmation and validation for how students feel and an acknowledgement of what they already know about slavery. Described as “co-processing,” this teaching tool enables the teacher to scaffold learning in order to empower students to move through a place of discomfort. Another example which includes a framework for teaching slavery includes Glenn Singleton’s curriculum entitled, “Courageous Conversations.” Singleton’s approach is unique because it utilizes four compass points to teach about the context in which slavery operated, including the moral, emotional, intellectual, and relational perspectives to enable students to process this hard history. Stang and Allen also advocate using primary sources of people who were enslaved when possible, in order to center their voices in the text.

Supreme Court Justice Henry Blackmun argued “ to get beyond racism we must first take account of race, there is no other way”. People in positions of power will reject and fight against the curriculum such as the 1619 project. When ignoring the racism that fueled this nation in the curriculum, many have argued that we, as a pluralistic nation, can not move forward. Teachers have an important role to play and need to learn how to lean into teaching hard history. Teacher prep programs should prepare educators to handle these topics effectively. People will disagree about this and feel discomfort. These issues have become highly politicized in this country and put a great deal of pressure on educators. Some districts and localities are not supportive of unearthing past wrongs, what they consider to be a shaming of the nation’s history and heroes. In this text, we continue to reshape the traditional narrative with a critical lens. We choose to include critical perspectives which traditionally have been left out because we know this is imperative to our nation’s healing and growth.

Critical Lens

Schools do not only control people; they also help control meaning. Since they preserve and distribute what is perceived to be ‘legitimate knowledge’—the knowledge that ‘we all must have,’ schools confer cultural legitimacy on the knowledge of specific groups. But this is not all, for the ability of a group to make its knowledge into ‘knowledge for all’ is related to that group’s power in the larger political and economic arena. Power and culture, then, need to be seen, not as static entities with no connection to each other, but as attributes of existing economic relations in a society. They are dialectically interwoven so that economic power and control is interconnected with cultural power and control. In the following article, Michael Apple, talks about how the educational system keeps this system of oppression – Michael Apple on Ideology in Curriculum

Precolonial America

In 1491, it is estimated that there were 2,000 distinct indigenous languages and approximately sixty million people. Many of these languages still exist today and carry clues of cultural, historical and traditional knowledge. The following video gives you a brief history of these complex and sophisticated communities which populated the Americas:

Video 2.1

Video 2.2

Much of what we know of these early communities comes from creation stories and archaeological evidence. In the following film, we learn about how Indigenous peoples were using agriculture, water management, deforestation practices, controlled burning, and urban development thousands of years before the arrival of Columbus. These practices were driven by a need for shelter, food and clothing for a growing population. Clearly, there were diverse systems of education to pass along such knowledge. The following film provides more detail about these innovative practices:

Video 2.3

While the oral tradition was the predominant educational practice in the Americas, the Maya had highly developed disciplines in writing, astronomy, math, art and architecture. They invented the concept of zero, an accurate calendar, and the only fully developed system of writing in the Americas which have allowed archeologists a chance to study their ancient culture in more detail.

Video 2.4

In most indigenous communities, storytelling was central to their education or transfer of knowledge. Stories were passed on from generation to generation. In the following video, Larry Cesspooch tells some of these stories and shares the history:

Video 2.5

North America in the 17th Century

Public education, as we know it today, did not exist in the colonies. In the First Charter of Virginia in 1606, King James I set forth a religious mission for investors and colonizers to disseminate the “Christian Religion” among the Indigenous population, which he described as “Infidels and Savages.” His colonial and educational mission would impact settlement and education in North America for centuries.

Puritan Massachusetts

Puritans in Massachusetts believed educating children in religion and rules from a young age would increase their chances of survival or, if they did die, increase their chances of religious salvation. Puritans in Massachusetts established the first compulsory education law in the New World through the Act of 1642, which required parents and apprenticeship masters to educate their children and apprentices in the principles of Puritan religion and the laws of the commonwealth. The Law of 1647, also referred to as the Old Deluder Satan Act, required towns of fifty or more families to hire a schoolmaster to teach children basic literacy. Because of similar religious beliefs and the physical proximity of families’ residences, formal schooling developed quickly in the commonwealth of Massachusetts. Connecticut, New York, and Pennsylvania followed in Massachusetts’ footsteps, passing similar laws and ordinances between the mid- and late-seventeenth century (Cremin, 1972).

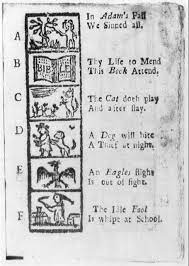

During this time, children learned to read at home using the Holy Scriptures and catechisms (small books that summarized key religious principles) as educational texts. The primers that were used “contained simple verses, songs, and stories designed to teach at once the skills of literacy and the virtues of Christian living” (McClellan, 1999, p. 3).

The importance of faith, prayer, humility, rewards of virtue, honesty, obedience, thrift, proverbs, religious stories, the fear of death, and the importance of hard work served as major moral principles featured throughout the texts. When Indigenous people were depicted or mentioned in texts, they were portrayed as “savages and infidels,” needing salvation through English cultural norms. In light of what we now know of the genocide of native peoples, the irony of who was performing the savagery should be re-examined.

Another form of education occurred in Dame schools. Dame schools were small private schools for young children run by women. Where available, some parents sent their children to a neighboring housewife who taught them basic literacy skills, including reading, numbers, and writing. Because families paid for their children to attend Dame schools, this form of education was mainly available to middle-class families. Teaching aids and texts included Scripture, hornbooks, catechisms, and primers (Urban & Wagoner, 2009).

More expensive than Dame schools, Latin grammar schools were also available. The Latin grammar schools were originally designed for only sons of certain social classes who were destined for leadership positions in church, state, or courts. The first Latin grammar school was established in Boston in 1635 to teach boys subjects like classical literature, reading, writing, and math at what we would consider the high school level today, in preparation to attend Harvard University (Powell, 2019).

In Colonial America, education in the mid-Atlantic and southern colonies was heavily stratified and remained out of reach for most inhabitants. The early recorded history of US education mostly addresses the education of white children. The assimilationist education of native peoples is addressed later in the chapter. Starting in the 1600s, millions of enslaved Africans were brought to the colonies to fuel the industry and wealth that built this nation..

Deeper Dive – Understand Slavery

Resources to Help You Understand Slavery

- “ Slavery to Mass Incarceration” Slavery in America

- 10 concepts of slavery offered from leading experts of the field through 10 videos: Teaching Hard History: American Slavery | Classroom Videos | Learning for Justice

It is important to note that enslaved people never stopped transferring knowledge, despite the horrific conditions of American slavery. The following video demonstrates the covert methods of communication they developed to communicate via their singing of spirituals.

Video 2.6

The institution of slavery meant that White landowners sent their children to private schools to train future land owners, and slaves were denied the right to an education. Literacy for enslaved people was outlawed and considered dangerous for white inhabitants who controlled all aspects of an evolving society. Nevertheless, brave individuals attempted to set up secret schools throughout the south. Northern schools for Blacks also faced harassment and threats. In the following articles, you can find more information regarding the education of African Americans, their literacy and the slavery of our ancestors.

Deeper Dive – Heroic Educators

Heroic Educators during this period

American Revolutionary Era

After the American Revolution, our new country was establishing its systems and identity. Many key Founders believed public education was a prerequisite to a democratic society. Three groups had distinct post-revolutionary plans for education and schooling, all of which were intended to serve as part of the founding process: Federalists, Anti-Federalists, and the lesser known Democratic-Republican Societies.

Federalist

“History has its eyes on you.”- from the musical “Hamilton”

Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, and John Adams, among other Federalists, focused on building a new nation and a new national identity by following the new Constitution, which consolidated power in a new federal government. The Federalists supported mass schooling for nationalistic purposes, such as preserving order, morality, and a nationalistic character, but opposed tax-supported schooling, viewing it as unnecessary in a society where elites rule.

As a Federalist, Noah Webster believed education should teach morality. Noah Webster was one of the great advocates for mass schooling to teach children not just “the usual branches of learning,” but also “submission to superiors and to laws [and] moral or social duties.” Smoothing out the “rough manners” of frontier folk was very important to Webster. Furthermore, Webster placed great responsibility on “women in forming the dispositions of youth” in order to “control…the manners of a nation” and that which “is useful” to an orderly republic (Webster, 1965, 67, 69-77). Webster’s treatise on education and his spellers (like his 1783 American Spelling Book) were intended to develop a literate and nationalistic character to shape useful, virtuous, and law-abiding citizens with strong attachments to Federalist America.

Anti-Federalists

Anti-Federalists, on the other hand, were opposed to a strong central government, preferring instead state and local forms of government. The Anti-Federalists believed that the success of a republican government depended on small geographical areas, spaces small enough for individuals to know one another and to deliberate collectively on matters of public concern. Anti-Federalists feared concentrated power.

As an Anti-Federalist, Thomas Jefferson believed education should be locally controlled. An aristocrat whose genteel lifestyle was bolstered by his violent oppression of enslaved people, Jefferson put forth proposals to educate all white citizens in the state of Virginia. Jefferson proposed a system of tiered schooling. The three tiers were primary schools, grammar schools, and the College of William and Mary. The foundation of his tiered schooling plan included three years of tax-supported schooling for all white children with limited options for a few poor children to advance at public expense to higher levels of education. While he suggested very limited educational opportunities for women, no other key Founder advocated giving high-achieving scholars from poor families a free education. Religion was not a core curricular area in the primary and grammar schools. However, his plans were viewed as too radical by his aristocratic peers, and they correspondingly rejected his state education proposals.

Pause and Ponder – Ideologies in Schools

Where do we see elements of these different ideologies in today’s schools? What has remained and what has changed? What approach do you see as the most valuable in terms of today’s public schools?

Early National Era (1789-1837)

During the early-to mid-nineteenth century, the United States was expanding westward, and urbanization and immigration intensified. This period of history was defined by the emergence of the common school movement and normal schools, though conflicts over the organization and control of education continued. This period also saw the advent of higher education.

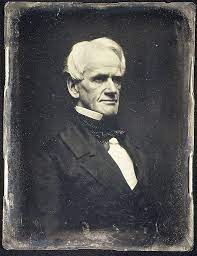

The Common School Movement

Horace Mann established the common school movement and also advocated for normal schools to prepare teachers. He was Massachusetts’s first Secretary of Education and Whig (formerly Federalist) politician, was the leader of the common school movement, which began in the New England states and then expanded into New York, Pennsylvania, and then into westward states.

Video 2.7

Common schools were elementary schools where all students–not just wealthy boys–could attend for free. Common schools were radical in their status as tax-supported free schooling, but their conservative-leaning curriculum addressed traditional values and political allegiance. Schooling offered increasing opportunities for children, especially those from working-class families, by teaching basic values including honesty, punctuality, inner behavioral restraints, obedience to authority, hard work, cleanliness, and respect for law, private property, and representative government (Urban & Wagoner, 2009).

The Development of Normal Schools

With the rise of common schools, Horace Mann then turned to how female teachers would be educated. For Mann, the answer was to create teacher training institutions originally referred to as normal schools. A French institution dating back to the sixteenth century, école normale was the term used to identify a model or ideal teaching institute. Once adopted in the United States, the institution was simply called a normal school.

Catherine Beecher, the first well-known teacher, became an instructor at a normal school to prepare other teachers. She played a significant role in influencing women to join the profession in large numbers, and made it acceptable for women to leave home and travel afar to become teachers, especially in the western territories of the growing nation.

The first normal school in America was established in Lexington, Massachusetts in 1839 (now Framingham State University). They were primarily used to train primary school teachers, as middle and high schools did not yet exist. The curriculum included academic subjects, classroom management and school governance, and the practice of teaching. Teacher credentialing began and was regulated by state governments. Moreover, this contributed to the professionalization of teaching, and normal schools eventually became colleges or schools of education or full-fledged liberal arts and research institutes. Catherine Beecher was the first well-known teacher of the time and one of the normal schools’ first teachers.

Administrators and policymakers began to see an opportunity in hiring women, mainly because they could justify paying them less than men, and because they were perceived to be gifted at working with children. As men were exiting the profession, more women were hired for less money to educate the growing ranks of students as common schools spread westward. Furthermore, once the profession was feminized, teaching became perceived as a missionary calling rather than an academic pursuit. While male policymakers insisted women were better nurturers and more suited to teaching morality and correct behavior in children, framing the discourse of teaching around a calling helped rationalize lower pay for women and fewer advancement possibilities.

Pause and Ponder – Females in the Educational System

How do you see the early roots of feminizing the teaching profession still in effect today?

Conflicts in the Common School Movement

The common school movement was not without its conflicts. Whigs (formerly Federalists), including Horace Mann, sought to establish state systems of schooling in order to create standardization and uniformity in curricula, classroom equipment, school organization, and professional credentialing of teachers across state schools. Democrats, however, often supported public schooling but feared centralized government, thus opposing the centralization of local schools under the common school movement. The battle between Whigs and Democrats during the nineteenth century represents one of the initial conflicts related to public schooling.

Another important conflict related to the common school movement was the clash between urban Protestants and Catholics. Typically from Protestant backgrounds, common school reformers continued to use the Bible as a common text in classrooms without considering the potential conflict this could generate in diverse communities. Horace Mann advocated using only generalized Scripture in order to prevent offending different sects. However, what appeared to Protestants as a generalization of Christian text was actually very insulting to Catholic immigrants, who were becoming the second largest group of city dwellers at the time. Protestant education leaders attempted to address this issue by reducing the religious content in the common school curriculum, but unhappy Catholic leaders created their own private parochial schools? This conflict generated a greater theoretical acceptance of the separation of church and state doctrine in publicly-funded common schools, though in practice, common schooling continued to infuse Protestant biases for over a century.

Common schools also faced conflict in Southern states, including Jefferson’s Virginia, until after the Civil War. Planters had no interest in disturbing the status quo by educating poor whites or enslaved people. Driven by Southern aristocracy, education continued to be viewed as a private family responsibility and class privilege. As described previously, many southern states prohibited educating enslaved people and passed state statutes that attached criminal penalties for doing so, such as the ones below.

Critical Lens – Excerpts

Excerpt from a 1740 South Carolina Act: Whereas, the having slaves taught to write, or suffering them to be employed in writing, may be attended with great inconveniences; Be it enacted, that all and every person and persons whatsoever, who shall hereafter teach or cause any slave or slaves to be taught to write, or shall use or employ any slave as a scribe, in any manner of writing whatsoever, hereafter taught to write, every such person or persons shall, for every such offense, forfeit the sum of one hundred pounds, current money.

Excerpt from Virginia Revised Code of 1819: That all meetings or assemblages of slaves, or free negroes or mulattoes mixing and associating with such slaves at any meeting-house or houses, &c., in the night; or at any SCHOOL OR SCHOOLS for teaching them READING OR WRITING, either in the day or night, under whatsoever pretext, shall be deemed and considered an UNLAWFUL ASSEMBLY; and any justice of a county, &c., wherein such assemblage shall be, either from his own knowledge or the information of others, of such unlawful assemblage, &c., may issue his warrant, directed to any sworn officer or officers, authorizing him or them to enter the house or houses where such unlawful assemblages, &c., may be, for the purpose of apprehending or dispersing such slaves, and to inflict corporal punishment on the offender or offenders, at the discretion of any justice of the peace, not exceeding twenty lashes.

Enslaved people have often been depicted in many American history textbooks as passive toward their owners. This misrepresentation is quite problematic and gives people across races a whitewashed, inaccurate understanding of the history of the US and our own individual heritages. African Americans escaped, committed espionage on plantations, negotiated statuses, and occasionally educated themselves behind closed doors. For enslaved people, education and knowledge represented freedom and power, and once they were emancipated, they continued their relentless quest for learning by constructing their own schools throughout the South, even with minimal resources. African Americans placed an exceptional value on literacy due to generations of bondage and denial of access to reading and writing.

Critical Lens – Words Matter

You will notice in this chapter that we use the term “enslaved person” instead of “slave.” Part of critical theory involves questioning existing power structures, even in word choice. Recently, academics and historians have shifted away from using the term “slave” and have begun replacing it with “enslaved person” because it places “humans first, commodities second” (Waldman, 2015, para. 2).

While slavery continued throughout the South, segregation continued in the North. One of the first challenges to segregation occurred in Boston, Massachusetts. Benjamin Roberts attempted to enroll his five-year-old daughter, Sarah, in a segregated white school in her neighborhood, but Sarah was refused admission due to her race. Sarah attempted to enroll in a few other schools closer to her home, but she was again denied admission for the same reason. Mr. Roberts filed a lawsuit in 1849, Sarah Roberts v. City of Boston, claiming that because his daughter had to travel much farther to attend a segregated and substandard black school, Sarah was psychologically damaged. The state courts ruled in favor of the City of Boston in 1850 because state law permitted segregated schooling. This case would be cited in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1898 and in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, both of which are pivotal to segregation cases in the US..

Post Civil War and Reconstruction (1863-1877)

Following the Civil War, significant restructuring of political, economic, social, and educational systems in the United States occurred. Political leaders considered education to be a necessary instrument in maintaining stability and unity. During this era, education was shaped by increasing influence of the federal government, the beginning of public education in the South, the Morrill Acts, and Native American boarding schools.

Increasing Influence of the Federal Government

Elazar (1969) asserted that “crisis compels centralization” (p. 51): when the nation undergoes a calamity, it eventually leads to the federal government exercising extra-constitutional actions on its own will or as a result of demands made by state and local governments. The post-Civil War Era provides one example of this effect. The U.S. Congress established requirements for the Southern states to reenter the Union. “Radical Republicans”, as they were identified after the Civil War, believed that the lack of common schooling in the South had contributed to the circumstances leading to war, so Congress required Southern states to include provisions for free public schooling in their rewritten constitutions. To learn more about these radical republicans, see the following video:

Video 2.8

Segregated “Jim Crow” America

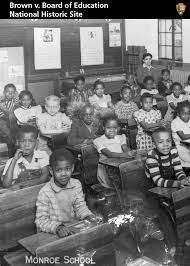

“After the Civil War, millions of formerly enslaved African Americans hoped to join the larger society as full and equal citizens. Although some white Americans welcomed them, others used people’s ignorance, racism, and self-interest to sustain and spread racial divisions. By 1900, new laws and old customs in the North and the South had created a segregated society that condemned Americans of color to second-class citizenship”. Separate is not Equal

Of course, southern states followed through with the requirements and drafted language supporting schools, but they created loopholes like separate and segregated schools in the “Jim Crow” era.

Video 2.9

Jim Crow was the White Supremacy system set up to separate and control Black citizens in all areas of civic, political, economic, legal and social life and the schools played a large role. Black schools received substantially lower funding than White schools, creating yet another form of institutionalized racism that would have long-lasting consequences for African American communities.

Critical Lens – Education of Black Children

- Learn more about the education of Black children in the Jim Crow South – The Education of Black Children in the Jim Crow South

- Learn more about the promise of Freedom – Separate is not Equal

- “Now we are free. What do we want? We want education; we want protection; we want plenty of work; we want good pay for it, but not any more or less than anyone else…and then you will see the down-trodden race rise up.” —John Adams, a former slave

- “Denied public educational resources, people of color strengthened their own schools and communities and fought for the resources that had been unjustly denied to their children. Parents’ demands for better schools became a crucial part of the larger struggle for civil rights”.

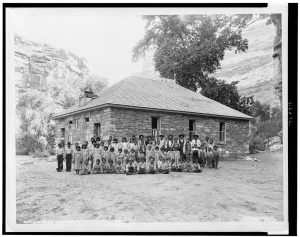

The Beginning of Education in the South

Following the Civil War, nearly four million formerly enslaved people were homeless, without property, and illiterate. In response, Congress created the Freedmen’s Bureau (officially referred to as the U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands). Supervised by northern military officers, the Freedmen’s Bureau distributed food, clothing, and medical aid to formerly enslaved people and poor Whites and created over 1,000 schools throughout the southern states. The Freedmen’s Bureau lasted only for seven years, but it represented a massive federal effort that provided some benefits.

In addition to Freedmen’s schools, Yankee schoolmarms also headed south as missionaries to help educate formerly enslaved people. They sought mutual benefits: to educate the illiterate and simultaneously secure themselves in the eyes of God. As missionaries, female teachers learned that their work was a calling to instill morality in the nation’s students, and this calling was pursued for the good of mankind instead of financial gain. This same missionary status fueled both the migration of teachers westward following national expansion and the thousands of schoolmarms that migrated to the South to educate formerly enslaved people who, they believed, had to be redeemed through literacy, Christian morality, and republican virtue (Butchart, 2010).

However, African Americans were primarily responsible for the education of their people. Formerly-enslaved people knew the connection between knowledge and freedom. Ignorance was itself oppressive; knowledge, on the other hand, was liberating. Literate African Americans were often teaching children and adults alike and creating their own one-room schoolhouses, even with limited resources. By 1866 in Georgia, African Americans were at least partially financing 96 of 123 evening schools and owned 57 school buildings (Anderson, 1988). The African American educational initiatives caught Northern missionaries off guard:

Many missionaries were astonished, and later chagrined…to discover that many ex-slaves had established their own educational collectives and associations, staffed schools entirely with black teachers, and were unwilling to allow their educational movement to be controlled by the ‘civilized’ Yankees.” (Anderson, 1988, p. 6)

In addition, industrial schools were built in the South for Black Americans. Southern policymakers, northern industrialists, and philanthropic groups partnered to establish industrial schools focused on vocational or trade skills. Southern policymakers benefited because industrial schools resulted in both segregating the workforce and higher education which aligned with their values. Northern industrialists benefited because they gained skilled laborers. Philanthropists believed they were giving Black Americans access to education and jobs.

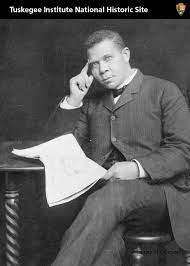

Booker T. Washington advocated for the industrial schools being established for African Americans. Washington believed in giving Black people knowledge of the trades, in order to earn a living.

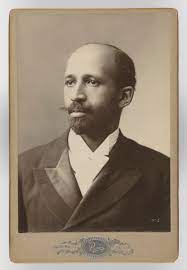

Two African American leaders in the late nineteenth century had different perspectives on newly-developed industrial schools. Booker T. Washington was born an enslaved person in 1856 and grew up in Virginia. He attended the Hampton Institute, whose founder, General Samuel Armstrong, emphasized that “obtaining farms or skilled jobs was far more important to African-Americans emerging from slavery than the rights of citizenship” (Foner, 2012, p. 652-653). Washington supported this view as head of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. In his famous 1895 “Atlanta Compromise” speech, Washington did not support “ceaseless agitation for full equality”; rather, he suggested, “In all the things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress” (Foner, 2012, p. 653). Washington feared that if demands for greater equality were imposed, it would result in a white backlash and destroy what little progress had been made. The Tuskegee Institute offered vocational training programs to help Blacks find what was considered more “respectable” careers.

W.E.B. Du Bois viewed the situation differently. Born free in Great Barrington, Massachusetts in 1868, Du Bois was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. He served as a professor at Atlanta University and helped establish the NAACP in 1905 to seek legal and political equality for African Americans. He opposed Washington’s pragmatic approach, considering it a form of “submission and silence on civil and political rights” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 176). He came from a very different background, lived in different circles in the North, and as a result, could envision a different future for Blacks, one that included upward mobility and higher educational aspirations. The two men are often contrasted for these different perspectives in what they felt was realistic for Black people of the time in terms of their education.

The Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890

Video 2.10

In addition to the Freedman’s Bureau, the federal government implemented two legislative acts related to education. The Morrill Act of 1862 gave states 30,000 acres of land for each senator and representative it had in Congress in 1860. The income generated from the sale or lease of this land would provide financial support for at least one agricultural and mechanical (A&M) college, known as a land-grant institution (Urban & Wagoner, 2009). Land-grant institutions were designed to support the growing industrial economy. The second Morrill Act of 1890 required “land-grant institutions seeking increased federal support…to either provide equal access to the existing A&M colleges or establish separate institutions for the ‘people of color’ in their state” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 188). The Morrill Acts demonstrated how industrialization and westward expansion resulted in increasing involvement of the federal government in education policy to meet national needs.

Pause and Ponder

Whose land was the state giving? and educating whom?

Consider this in the context of the next section.

Native American Boarding Schools: Cultural Imperialism and Genocide

Native American boarding schools were designed to take away Indigenous culture and assimilate Indigenous children into mainstream American culture.

Critical Lens

In the following clips, you can hear some real stories about cultural genocide:

Using its military, the federal government created over 400 Native American boarding schools across 37 states. The first and most famous of these was the Carlisle School, founded in Pennsylvania in 1879. The federal government convinced many Native American parents that these off-reservation boarding schools would educate their children to improve their economic and social opportunities in mainstream America. In reality, these schools were intended to deculturalize Indigenous children. Supervisors at the boarding schools destroyed children’s native clothing, cut their hair, and renamed many of them with names chosen from the Protestant Bible. The curriculum in these schools taught basic literacy and focused on industrial training; graduates of these boarding schools were to be sorted into agricultural and mechanical occupations. A total of 25 off-reservation boarding schools educating nearly 30,000 students were created in several western states and territories, as well as in the upper Great Lakes region. Based in ethnocentrism, the belief that their white protestant culture was superior to other cultures, these boarding schools relied on a harsh form of assimilation, a fundamental feature of common schooling.

Deeper Dive – Indigenous Boarding Schools

In the summer of 2021, the dark history of Indigenous boarding schools made headlines as Canadian authorities discovered unmarked graves and remains of children[3] killed at multiple boarding schools for Indigenous children. In July 2021, the U.S. launched a federal probe[4] into our own Indigenous boarding schools and the intergenerational trauma they have caused. These boarding schools are one way that education has been used to oppress and de-culturize a particular group of Americans who have experienced intergenerational trauma. Recognizing and teaching this tragic history is one small step toward dismantling the colonizer/settler/founders mythology.

Video 2.11

Today

Throughout the centuries, the debate over what is taught in schools has always been fraught with conflict, and this modern era is no different. As a result, different schools of thought emerged in this conflict as you read about in chapter 3. If you follow the local news, you can’t help but see that these battles are fought daily. One cannot deny the political nature of schooling, despite efforts to sanitize it, because schooling occurs in a cultural context and a public domain.

Pause and Ponder

Many schools have used indigenous symbols and stereotypes as their mascots and still do. What is the impact on native communities- and white communities when these practices persist? What impact does it have on young children and on our shared future as a pluralistic society?

The Progressive Era (1896–1917)

The Progressive Era was defined by reform across all aspects of society, and education was no exception. Many of the philosophies you learned about earlier in this chapter were established in the Progressive Era. Changes in education during this period included varying forms of progressivism, the emergence of critical theory, extending schooling beyond the primary level, and the development of teacher unions.

Differing Approaches to Progressivism

During the Progressive Era’s focus on social reform, different approaches emerged. The administrative progressives wanted education to be as efficient as possible to meet the demands of industrialization and the economy. Efficiency involved centralizing neighborhood schools into larger urban systems, allowing more students to be educated for less money. Graded classes, specialized and differentiated subject areas, ringing bells, an orderly daily itinerary, and hierarchical management–with men serving as school board members, superintendents, and principals, and women on the bottom rung as teachers–also increased educational efficiency. Educational efficiency required preparing good workers for a rapidly changing economy. Administrative progressives adopted factory models in schools to become better at processing and testing the masses, a continued form of educational assimilation.

Similar to actual factories, factory models in education increased efficiency, which was important to administrative progressives.

Curricular or pedagogical progressives were focused on changes in how and what students were learning. Many of these progressives saw schooling as a vehicle for social justice instead of assimilation. John Dewey is often referred to as America’s philosopher and the father of progressivism in education. In Democracy and Education, Dewey (1944) theorized two types of learning: “conservative,” which reproduces the status quo through cultural transmission and socialization, and “progressive,” which frames education more organically for the purposes of experiencing “growth” and activating“potentialities” (p. 41). For curricular and pedagogical progressives, “progressive” learning has no predetermined outcome and is always evolving, or progressing. Democratic education, Dewey believed, must build on the existing culture or status quo and free students and adults alike toward conscious positive change based on newly-discovered information, improvements in science, and democratic input from all members of the community, which added legitimacy to a society’s growth.

John Dewey was known as the father of progressive education.

Dewey and like-minded progressives have often been referred to as social reconstructionists. They believed education could improve society. Dewey recognized “the ability of the schools to teach independent thinking and the ability of students to analyze social problems” (Kliebard, 1995, p. 170). Dewey did not expect the school to upend society; rather, as institutions that reached virtually all youth, he saw schooling as the most effective means of developing the habits of critical thinking, cooperative learning, and problem solving so that students could, once they became adults, carry on this same activity democratically in their attempts to improve society. The progressives were often met with contempt because such critique threatened the existing socio-political system, which conservative individuals wished to preserve.

Emergence of Critical Theory

In Germany in 1923, critical theory was developed at The Frankfurt Institute of Social Research. With roots in German Idealism, critical theorists sought to interpret and transform society by challenging the assumption that social, economic, and political institutions developed naturally and objectively. In addition, critical theorists rejected the existence of absolute truths. Instead of blind acceptance of knowledge, critical theorists encouraged questioning of widely accepted answers and challenged objectivity and neutrality, noting that these constructs avoid addressing inequality in political and economic power, social arrangements, institutional forms of discrimination, and other areas. The original Frankfurt School theorists were dedicated to ideology critique and the long-term goal of reconstructing society in order to “ensure a true, free, and just life” emancipated from “authoritarian and bureaucratic politics” (Held, 1980, p. 15).

A decade later amidst the Great Depression, America witnessed the emergence of its own Frankfurt School. In the United States, critical theory was aligned with social reconstructionism and situated in social foundations programs in various academic institutions, including its first department in Columbia University’s Teachers College. Why would this movement find its home in American education? Educators were “a positive creative force in American society” that could serve as “a mighty instrument of…collective action” (Counts, 2011, p. 21). Critique, reflection, and action, often referred to as praxis, are intrinsically educational, and these actions transcend the mere transmission of knowledge and culture. America’s social reconstructionists attempted to cultivate a specialized field that drew from many academic disciplines in order to develop professional teachers’ understanding of how schooling tended to reinforce, evangelize, or perpetuate a given social order. They repudiated a predetermined “blueprint” for training teachers, rejecting “the notion that educators, like factory hands, merely…follow blueprints” (Coe, 1935, p. 26).

Social reconstructionists viewed teachers as professionals who did not need “blueprints” to tell them exactly how to teach. More on philosophical approaches to education in chapter 3.

Pause and Ponder – What is the purpose of education?

Is it the transmission and indoctrination of the values, customs, ideologies, beliefs, and rituals?

OR

Should education serve as a means of critique and social reconstruction in order to improve society?

Deeper Dive

“It would seem to me that when a child is born, if I’m the child’s parent, it is my obligation and my high duty to civilize that child. Man is a social animal. He cannot exist without a society. A society, in turn, depends on certain things which everyone within that society takes for granted. Now the crucial paradox which confronts us here is that the whole process of education occurs within a social framework and is designed to perpetuate the aims of society. Thus, for example, the boys and girls who were born during the era of the Third Reich, when educated to the purposes of the Third Reich, became barbarians. The paradox of education is precisely this – that as one begins to become conscious one begins to examine the society in which he is being educated. The purpose of education, finally, is to create in a person the ability to look at the world for himself, to make his own decisions, to say to himself this is black or this is white, to decide for himself whether there is a God in heaven or not. To ask questions of the universe, and then learn to live with those questions, is the way he achieves his own identity. But no society is really anxious to have that kind of person around. What societies really, ideally, want is a citizenry which will simply obey the rules of society. If a society succeeds in this, that society is about to perish. The obligation of anyone who thinks of himself as responsible is to examine society and try to change it and to fight it – at no matter what risk. This is the only hope society has. This is the only way societies change”.

James Baldwin

Extending School Beyond the Primary Level

While high schools existed in New England towns since the establishment of the Boston Latin Grammar School in 1636, it was not until the early nineteenth century that high schools started appearing in urban areas, and they were not commonly attended until the early twentieth century. While common elementary schooling focused on teaching students morality, a differentiated curriculum in the early twentieth century high schools “reflected a new, largely economic, purpose for education” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 234). Debates arose around the high school curriculum: should it teach a classical curriculum, or focus on vocational training to meet the needs of the rapidly changing economy in the U.S.? In 1918, the National Education Association published a report called “The Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education” to establish the goals of high school education, including “health, command of fundamental processes, worthy home membership, vocation, citizenship, worthy use of leisure, and ethical character” to prepare students “for their adult lives” by “fitting [them] into appropriate social and vocational roles” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 271-272). The functionalistic nature of high school also resulted in the development of extracurricular programs including, but not limited to, “athletics,” school “newspapers, and school clubs of various kinds” in order to teach “students the importance of cooperation” and to “serve…the needs of industrial society” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 272-276). This resulted in the high school becoming a major institutional mechanism in developing the future teenager.

Pause and Ponder

How did these “Cardinal Principles,” published over a century ago, shape your own high school experience?

Changes beyond high school also occurred in the Progressive Era. It was also during this period that the educational ladder expanded to include not only a system of elementary and high schools, but also junior high schools, community colleges, and kindergartens, which had served as separate private institutions since the mid-nineteenth century. Not only were more children attending school at this time, they were attending for longer periods of time due to protections developed through progressive child labor laws, especially the Child Labor Law of 1938.

Video 2.12

Deeper Dive – Progressive Education in the 1940s

Video 2.13

Intelligence Testing

It was introduced to education following World War I. Based on French psychologist Alfred Binet’s work on intelligence, Louis Terman developed the Binet-Terman scale of intelligence and despite his own impoverished upbringing, eschewed a framework of intelligence based on biological factors. Terman redirected Binet’s work and reduced intelligence to a single number on a scale that he termed the Intelligence Quotient (IQ). Terman associated intelligence with ethnicity, aligning with pernicious racist and Eugenist ideas of the time, linking certain intelligences to certain groups such as Blacks, Mexicans, Native Americans, and Southern Europeans and anyone with a perceived disability or difference. Furthermore, Terman portrayed intelligence as something fixed and hereditary, linking intelligence scores to the kind of educational or career opportunities people could access. These tests had tremendous far-reaching impacts as they were used to sort recruits for World War I, condemning those who scored lower to the front lines and the risk of death, and assigning those who scored higher to safer desk jobs.. Terman also strove to test and sort US school children, going on to create national exams to track the nation’s school children in all grades, again with far-reaching consequences, including intergenerational damage. While there have been many well-documented critiques of the cultural bias in standardized tests of intelligence (such as Gould’s The Mismeasure of Man), Terman and his colleagues wielded significant influence that still impacts and shapes schools today.

Pause and Ponder – Two professors discuss Terman

Watch the Psychological Testing Movement video and stop and ponder: How do you see Terman’s influence in schools today?

Post World War II & Civil Rights Era (1940-1949)

In the decades following World War II, the U.S. prospered, and education saw many significant shifts, especially focusing on equality of educational opportunities. In this period, ongoing inequalities in educational opportunities led to limited federal funding; Brown v. Board of Education (1954) deemed segregated schools illegal; and other minority groups continued to fight for equitable access to education.

Ongoing Inequities and Federal Funding

The 1945 Senate committee hearings on federal aid to education highlighted ongoing inequities in schooling, as well as the fact that “education was in a state of dire need” of financial resources and more equitable funding (Ravitch, 1983, p. 5). Most school funding came from property taxes, which continued to exacerbate inequities because ….. Other changes took place following World War II to worsen already existing inequalities. After the War, “white flight” from the inner city to suburbs resulted in highly-segregated communities, falling urban property values, and rising suburban property values. White flight contributed to greater de facto segregation, and it increased segregated schooling and enhanced inequalities in school funding.

After Russia launched Sputnik in 1957, U.S. federal support of schools increased to allow for global competition.

In response, the federal government offered limited assistance. The National School Lunch Program was passed in 1946 in order to enhance learning through better nutrition. In response to the anxiety created over the launching of the Russian satellite Sputnik, Congress passed the 1958 National Defense Education Act, which provided increased federal funding for math, science, and foreign languages in public schools. While these examples are not exhaustive, they illustrate the piecemeal federal approach to funding public schools: if a problem was perceived as a crisis and reached the federal legislative agenda, it was more likely to attract congressional funding.

In 1965, President Johnson worked with Congress in order to pass what became known as the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). The ESEA served as the largest total expenditure of federal funds for the nation’s public schools in history. Aligned with Johnson’s war against poverty, the purpose of the law included increased federal funding for school districts with high levels of poor students. The law included six Titles (sections). Title I served as the primary legislative focus and included about 80 percent of the law’s total funding. Title I funds were distributed to poorer schools districts in an attempt to remedy the unequal funding perpetuated by reliance on property taxes. Title VII, or the Bilingual Education Act of 1968, provided funds for schools with students who were speakers of languages other than English. The other Titles provided federal funding for school libraries, textbooks and instructional materials, educational research, and funds to state departments of education to help them implement and monitor the law. This title funding resulted in the growth of state power alongside the expansion of federal power since states gained greater oversight of federal programs and mandates.

Separate is not Equal

The landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision began the process of school desegregation, which took several decades.

In 1896, Plessy v. Ferguson established the separate-but-equal doctrine. In its decision, the U.S. Supreme Court circumvented the original intent of the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, which was intended to give all persons equal rights under the law. The Court strategically interpreted the clause to mean that as long as segregated public facilities were “equal,” they were constitutional.

The 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision ended the separate-but-equal doctrine. Prior to this ruling, segregation was mandated by law (also called de jure segregation). The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) found five plaintiffs representing four different states (Delaware, Kansas, South Carolina, and Virginia) and the District of Columbia to challenge segregated primary and secondary schools. All five cases were heard under the name Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. The Court ruled unanimously in 1954 to overturn Plessy. In his majority decision, Chief Justice Earl Warren made the following conclusion:

Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group…Any language in contrary to this finding is rejected. We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. (347 U.S. 483, 1954)

Even though Brown v. Board found segregation unconstitutional, desegregation faced many challenges from White students, families, educators, and others. White Supremacists actively fought integration and used threats and ultimately force to intimidate communities of color who were trying to gain access. The US would continue to try to undo the harm of segregated schools for many decades to come, and that work continues, even as schools have grown more segregated in practice.

After ruling segregation unconstitutional, the Court then had to consider a reasonable set of remedies in order to ensure desegregation. In 1955, The Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka II that desegregation would occur “on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate speed.” This vague language, particularly the phrase “all deliberate speed,” contributed to chaos and enabled state resistance, with each state and district deciding its own approaches or avoidance thereof (Ryan, 2010).

When attempted integration efforts occurred, they occurred on white terms, determined by white school boards. Desegregation efforts resulted in Black teachers losing their jobs and the closing of their schools. Black students were integrated into White schools and were suddenly being taught by White teachers while being subjected to an all-white curriculum that didn’t include their voices or perspectives. Black students and teachers alike experienced “cultural dissonance that exacerbated student rebelliousness, especially among African American boys.” Furthermore, “the actual implementation of integration plans and court orders remained largely in the hands of white school boards” (Fairclough, 2007, p. 396-400). Due to massive resistance to desegregation, Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act in an attempt to force compliance. Following the passage of ESEA, which provided millions of federal dollars to each state, the federal government could now threaten non-compliant states (and school systems) with withholding these large sums of money annually under Title VI of the act if they did not comply with the mandate to desegregate schools.

Deeper Dive – The unintended consequences of Brown vs Board of Education

Video 2.14

As you see in the video above, Thousands of Black teachers and administrators were fired.

Why do you think such a decision was made and what impact did it have on Black children in particular, on desegregation efforts?

Busing children to different schools not in their neighborhoods was one attempt to increase racial diversity in schools.

Many urban school systems began drawing plans to bus white and non-white children to schools across neighborhoods in order to increase racial diversity in all of a district’s schools (i.e., Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 1971). However, in 1974 in Milliken v. Bradley, the U.S. Supreme Court decided schools were not responsible for desegregation across district lines if their own policies had not explicitly caused the segregation. President Nixon, who opposed inter-district busing, argued that in order to protect suburban schools, inner city schools should be given additional funds and resources to compensate urban school children from the harms of past segregation and the legacies of inequitable funding (LCCHR, n.d.). According to Ryan (2010), “Nixon’s compromise, broadly conceived to mean that urban schools should be helped in ways that [did] not threaten the physical, financial, or political independence of suburban schools… continues to shape nearly every modern education reform” (p. 5). The Milliken decision halted any possibility to integrate schools effectively. Due to the existence of de facto segregation, there was no way to significantly integrate students unless they crossed district boundaries.

Nixon also worked with Congress to pass the 1974 Equal Educational Opportunities Act. This legislation embodied the rights of all children to have equal educational opportunities, and it included particular consideration to Multilingual Learners. The EEOA prohibited states from denying equal educational opportunity on account of race, color, sex, or national origin. Moreover, the EEOA prohibits states from denying equal educational opportunity by the failure of an educational agency to take appropriate action to overcome language barriers that impede equal participation by its students in its instructional programs.

Increasing Access to Education for Minority Groups

The African American Civil Rights Movement gave hope to Mexican and Asian Americans, as well as women, people with disabilities, and to a lesser extent, Native Americans. Like African Americans, Mexican Americans utilized the courts to overturn segregated schools in the southwest, particularly in Texas and California. In fact, the earliest segregation case was filed by Mexican Americans in 1931 in Lemon Grove, California[7]. Other cases would be filed in the 1940s and 1950s, including Mendez v. Westminster[8] in 1947.

Women continued to fight for equal pay and respect in the workplace, and some success was achieved in the passage of Title IX as one of the amendments to the 1972 Higher Education Act. Title IX “prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in any federally funded education program or activity” in “colleges, universities, and elementary and secondary schools,” as well as to “any education or training program operated by a receipt of federal financial assistance,” including intercollegiate athletic activities (The U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.).

A class action suit in San Francisco, California, led to legal rights for English Language Learners. In Lau v. Nichols (1974), parents of approximately 1,800 diverse multilingual students alleged that their Fourteenth Amendment equal protection rights had been violated because because they could not access the language of instruction. The U.S. Supreme Court concluded that the school district violated Section 601 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination based “on race, color, or national origin” in “any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.” As recipients of federal funds, schools were required to respond to the needs of English language learners effectively, whether this meant implementing bilingual education, English immersion, or some other method of instruction. The Court concluded, “There is no equality of treatment by providing students with the same facilities, textbooks, teachers and curriculum, for students who do not understand English are effectively foreclosed from any meaningful education.”

Children with differing educational needs due to variety of differences and disabilities had been excluded from many educational opportunities. Prior to 1972, students with special needs had no access to a public education and were largely neglected in terms of any academic development in institutions and private residences. In 1972, Pennsylvania Association for R*tarded [sic] Children (PARC) v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania[9], guaranteed the rights of disabled children to attend free public schools. Congress followed up in 1973 by enacting the Rehabilitation Act, which guaranteed civil rights for people with disabilities, including appropriate accommodations and individualized education plans to tailor education for students based on their unique needs. Providing children special educational services in least restrictive settings was required by the 1975 Education for All Handicapped Children Act. “Least restrictive” essentially means that students with special needs should be in the same classrooms with other students as much as possible with the least restrictions possible. The video below shows the horrific atrocities that such students used to face in state-run boarding schools.

Pause and Ponder – Special Needs Students

How are students with special needs served today

Film 2.15

The 1980s and Beyond

In the 1980s and beyond, education saw increasing federal supervision and support, though ultimate control of education still remained with individual states. In this period, the Department of Education was established, and the A Nation at Risk report led to standards-based reforms like No Child Left Behind,.

Establishing the Department of Education

While the federal government has no constitutional authority over public education, its power and influence over schooling reached a pinnacle after the 1980s. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter created the federal Department of Education. Ronald Reagan, who succeeded Carter, tried and failed to abolish it. Reagan’s neo-conservative followers largely consisted of traditionalists and evangelicals. The traditionalists believed moral standards and respect for authority had been declining since the 1960s, while evangelicals (also known as the Religious Right) were concerned by increasing U.S. secularism and materialism (Foner, 2012). For example, in Engel v. Vitale (1962), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that directed prayer in public schools was a violation of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, which forbids the state (public schools and their employees) from endorsing or favoring a religion. While the Religious Right saw this decision as taking God out of America’s public schools, the Court viewed separation of church and state as necessary to protect religious freedoms from government intrusion. As established earlier in this chapter, however, even when presented in secular terms, the moral values taught in the public schools were often based on or connected to Protestant Christianity, so church influence was never truly separated from schooling.

Pause and Ponder – Education in the US

Consider how education in the US is impacted by 3 different levels of government: local, state, and federal control.

Which historically has had the most control over schooling and curriculum?

How do these 3 levels of governance provide a check and balance system to US schools? How might they not?

A Nation at Risk and Standards-Based Reform

In 1981, Reagan created the National Commission on Excellence in Education to address the perceived problems of educational decline. In 1983, the commission released a 71-page report entitled A Nation at Risk. The authors of the report, who were primarily from the corporate world, declared, “American students never excelled in international comparisons of student achievement and that this failure reflected systematic weaknesses in our schools and lack of talent and motivation among American educators” (Berliner & Biddle, 1995, p. 3). However, A Nation at Risk was somewhat “sensational” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 402), containing numerous claims that were uncorroborated or misleading generalizations as a pretense for a larger political agenda intended to discredit public schools and their teachers.

Developing the perception that America’s schools were in crisis, A Nation at Risk justified a top-down, punitive approach to school reform. While state-by-state standards-based reform had been underway for several years as primarily, A Nation at Risk inspired new theories about ‘systemic’ reform, which emphasized renewing academic focus in schools, holding teachers accountable for educational outcomes, measured by students’ academic achievement, and aligning teacher preparation and pedagogical practice with content standards, curriculum, classroom practice, and performance standards” (DeBray, 2006, p. xi).

Pause and Ponder – Standard-Based Reform

What are some of your own experiences with standards-based reform?

How has increasing standardization of schools helped or hurt your own learning experience?

President George W. Bush signs into law the No Child Left Behind Act Jan. 8, 2002, at Hamilton High School in Hamilton, Ohio. The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB, 2001) was an example of standards-based reform. As a bipartisan-passed reauthorization of the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act, it was “the first initiative to truly bring the federal government as a regulator into American public education” (Fabricant & Fine, 2012, p. 13). Previously, the federal government’s control of schools typically extended only to funding; now, NCLB would hold schools, teachers, and students accountable for passing standardized tests given annually in math and reading in grades 3-12. The law also required states to test English language learners for oral, written, and reading proficiency in English each year. Often unacknowledged, this bipartisan bill was intended to address inequities in US schools and while the implementation was far from perfect, certain aspects remain:

- Accountability for student performance on biased standardized tests; public characterization of schools as succeeding or failing based on those scores

- Heightened communication with parents and the community at large.

- Data-driven decision making to guide school improvement (looking at relationship between academic achievement and race)

- Enhanced preparation of educators; requirements for teachers to be “highly qualified” in their content areas (qualified math teachers are teaching math)

In the past, parents did not always know when schools were failing their children. NCLB sought to change that. ESEA was originally created to affect equity in terms of poverty in US schools. The federal government plays a role checking the local and state control of US schools.

Initially, there was strong progressive support for NCLB given the low standards and expectations of many schools attended primarily by students of Color and students from low income families. It was hoped that setting uniform standards would help raise achievement in those schools. However, NCLB’s acute focus on the results of narrow standardized tests resulted in teachers ‘teaching to the test’ using uniform curricula that have little or no connection to an increasingly diverse student population. Not only did NCLB publicize school performance on standardized tests, it punished schools that performed poorly. [Sentence elaborating on the punishment]. The punitive nature of the law harmed many students, teachers, and administrators. Madaus et al. (2009) asserted that as a result of changes arising from NCLB, testing “is now woven into the fabric of our nation’s culture and psyche,” which is evidenced by the fact that even “the valuation of homes in a community can increase or decrease based on [school] rankings” based on test scores (p. 4-5). NCLB is based on a theory of action that assumes that uniformity, standardization, centralization, and punitive measures can compel learning and decrease achievement gaps. The assumption that all children learn uniformly in all respects reveals a lack of understanding of the complexity of the learning process and the various demographic differences among children in a diverse society, including cultural, language, and ability differences.

Pause and Ponder

Can you think of a time when it was important for the federal government to intervene in America’s schools?

Critical Lens – Standardized testing

In a society experiencing greater diversity, it is more important than ever to realize how culture plays a significant role in shaping children’s school experiences, which makes standardized assessments all the more problematic as they tend to be culturally biased. Therefore, relying on standardized assessments in making conclusions about student achievement (or lack of achievement) limits teachers’ opportunities to identify the true strengths and learning needs of their students. . Rote memorization and test preparation skills can easily inhibit creativity and imagination, and such rigid approaches are teacher-centered and assimilatory.

In 2015, the No Child Left Behind Act (originally the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965) was reauthorized as the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). The law:

- Advances equity by upholding critical protections for America’s disadvantaged and high-need students.

- Requires that all students in America be taught to high academic standards that will prepare them to succeed in college and careers.

- Ensures that vital information is provided to educators, families, students, and communities through annual statewide assessments that measure students’ progress toward those high standards.

- Helps to support and grow local innovations, including evidence-based and place-based interventions developed by local leaders and educators.

- Sustains and expands investments in increasing access to high-quality preschool.

- Maintains an expectation that there will be accountability and action to effect positive change in our lowest-performing schools, where groups of students are not making progress, and where graduation rates are low over extended periods of time (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.).

By specifically tying federal funds to standardized assessments, standardized curricula, and accountability measures, along with requiring states and state education agencies to devote extraordinary resources toward fulfilling these mandates through oversight, since 2001 the federal government has more actively controlled America’s public schools than ever before. Increased federal influence illustrates the underlying belief that if the U.S. is going to maintain economic superiority and global competitiveness, public schooling must become a national responsibility. Contemporary goals focusing on preparing children to compete globally are significant for a number of reasons, not the least of which include the evolving nationalization of our public schools and the simultaneous loss of local authority and discretion over fundamental matters related to student learning.

Conclusion

Education in the United States has a complicated past entrenched in religious, economic, national, and international concerns. In Colonial America, Puritans in Massachusetts expected that education would teach children the ways of religion and laws, vital to their own survival in a new world. Meanwhile, the Middle and Southern Colonies viewed education as a commodity for the wealthy families who could afford it, and a way to perpetuate their economic system. After the American Revolution, Federalists, Anti-Federalists, and Democratic-Republican Societies all had different perceptions of how schools should be organized to support our newly-established independent nation. In the Early National Era, common schools, normal schools, and higher education grew as education became more widely established. Many groups were excluded from the early educational system due to racism, sexism, classism, heterosexism, to name a few, reflecting the dominant narrative of the times which was white-centered, English-speaking, protestant, patriarchal and ableist.

Following the Civil War, the federal government was increasingly involved in education, including the temporary creation of the Freedmen’s Bureau and subsequent federal funding of agricultural and mechanical colleges with the passage of the Morrill Acts. In the Progressive Era, efforts to maximize the efficiency of educational systems and to utilize education as a venue for social reform prevailed. After World War II, equitable access to education became a primary focus, as “separate-but-equal” doctrines were overthrown and schools grappled with institutional discrimination against non-White students, students with disabilities, women, and English Learners.