6 Teaching and Learning

“Pedagogy is always about power, because it cannot be separated from how objectives are formed, desires mobilized, how some experiences are legitimized and others are not, or how some knowledge is considered acceptable while other forms are excluded from the curriculum.”

Henry A. Giroux, 2013

Learning Objectives

- Introduce a variety of ways of knowing and pedagogical strategies

- Differentiate between dominant narratives and counternarratives

- Compare student-centered vs teacher-centered instructional strategies and the pedagogical approaches behind them

- Describe the characteristics of contemporary learners

| Pedagogy is a word you will encounter often in your teacher prep path as well as your practice. Pedagogy is defined as the philosophy of teaching and learning. Pedagogical strategies are the things we do to bring about and support teaching and learning. |

This chapter introduces a variety of general pedagogical strategies which span a broad spectrum, from student centered at one extreme to teacher centered at the other. Bloom (1956) created a hierarchy that classifies thinking from a low cognitive load, knowledge, to high cognitive load, creating. Bloom’s Taxonomy is often used by effective teachers to write clear learning objectives to meet the standards of the lesson. There are many ways to approach the art and science of teaching and learning, depending on whose cultures and histories we focus on. This chapter is intended to provide a brief intro to various ways of serving the needs of diverse learners.

6.1 Ways of Knowing and Learning

Stop and Think

Have you ever stopped to consider what you know and how you know it? Maybe you know how to ice skate, or that the freezing point of water is 32 degrees Fahrenheit, or that you should brush your teeth each morning. Perhaps you know how to divide fractions or read music. You might know your sister is mad because of the way she looked at you this morning. Think of an example of something you do every day. How do you know how to do this task?

To learn is ‘to gain knowledge or skill by studying, practicing, being taught, or experiencing something’, based on the Merriam-Webster online dictionary. This definition suggests that learning is something you gain or acquire and there are multiple ways to acquire knowledge. Schools are not the only place people learn. We begin to acquire knowledge from the moment we are born.

There are three general types of knowledge that we acquire, as described in the Western world. The most basic is knowledge by acquaintance: developed as a direct result of awareness and interaction with the world (attributed to Bertrand Russell). A second kind of knowledge is factual or declarative knowledge and is often referred to as knowledge that we acquire when we learn the capitals of states, types of dog breeds, or the names of scientists. A third is procedural knowledge and can be described as knowing how to do something: ice skate, make cookies, kick a ball, speak, write your name, etc. Schools focus mostly on declarative and procedural knowledge (Saks et al, 2021).

In a teacher education program, for example, a student may memorize principles of culturally responsive teaching as declarative knowledge, but may have little grasp of how these principles would be used in a classroom. What the student needs is to develop procedural knowledge so that they can actually develop an understanding of how to teach in a culturally responsive way. The distinction between declarative and procedural knowledge is embodied in the work of learning theorists, such as Benjamin Bloom. Bloom’s analysis contrasted lower levels of learning (i.e., knowledge, comprehension), which emphasized facts, concepts, and rules, and “higher‑order” learning (i.e., application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation), which emphasized how knowledge is used as part of higher level cognitive processes. His taxonomy is frequently referred to in the US education system and will be reviewed later in the chapter. Blooms Taxonomy is also addressed in the context of assessment in Chapter 8.

Procedural knowledge is not always more complex and can be quite simple, such as knowing how to brush one’s teeth. Also, procedural knowledge is often “automated” due to frequent repetition, so we may engage in the procedure without much conscious awareness. For adults, driving a car in familiar surroundings may become an automated procedure. We often will not recall how many lights we stopped at on our way home, for example. Reading also becomes an automated process, no longer requiring full conscious effort to decode and comprehend familiar text. It is sometimes declarative knowledge that challenges us, when the topic is less familiar or infrequently accessed, such as when asked about elements in the periodic table or leaders of the 18th century in Latin America.

Most learning combines both declarative and procedural knowledge. You know the elements necessary for a persuasive essay and you apply them creatively to suit your needs based on what you know of your intended audience or the teacher for whom you are writing the assignment. In many cases, teachers’ instructional goals include acquisition of both declarative and procedural knowledge. We rarely learn facts for their own sake (though sometimes it might seem like it) but instead develop knowledge so that we can apply it for specific purposes.

Video 6.1

Over the past few decades, research in social and cognitive psychology, as well as anthropology has made it clear that learning takes place in settings that have specific cultural and social norms. These norms or expectations influence the learning and transfer significantly. (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000) This is why it’s critical that teachers create classrooms where the norms and expectations create strong conditions for learning for each of their students. One way to support all learners in achieving academic success is to implement culturally responsive teaching strategies. Key characteristics of culturally responsive pedagogy (Hammond, 2014) include:

- communicating high expectations,

- actively engaging students in learning,

- providing an appropriate level of challenge to increase intellectual capacity,

- having a positive perspective on parents and families, and

- helping students understand how the curriculum links to their everyday lives.

Just under 100 years ago, simple reading, writing, and calculating were the goal of schooling. Basic declarative and superficial procedural knowledge were sufficient. Educational systems did not typically train people to think and read critically, to express themselves clearly, or to solve complex problems. Now, complex literacy skills are required of almost everyone to navigate in our current global landscape. Demands for more sophisticated skills at work have increased dramatically . Meaningful participation in the democratic process has become increasingly complicated as local, national, and international issues are increasingly intertwined. New science of learning is providing knowledge to significantly improve people’s abilities to become active learners who seek to understand complex subjects and are better prepared to transfer what they learn to new problems and settings. It is imperative that teachers learn and implement strategies that nurture the academic potential of all students, regardless of background, experience or identity, so they can succeed in our increasingly complex world.

6.2 The Dominant Narrative

There’s an old saying in the US. There are three sides to a story: one side, the other side, and what really happened. In any society, the side of the story that is most upheld by the political, legal, and economic structures of that society is called the dominant narrative.

Formal public education in the US is firmly grounded in the dominant narrative. The dominant narrative includes stories about who we are and what the country is. One example of a dominant narrative in US history lessons is how westward expansion gave people in the US economic opportunity. Additional examples of dominant narrative in the field of teacher education are the commonly taught ideas around how children learn, what the best way is for them to demonstrate learned knowledge, and values around sharing that knowledge in a competitive or collaborative way.

Counter narratives highlight alternative ideas to dominant narratives. Counter narratives can include facts that haven’t been shared in common history lessons. One example of this would be the genocide of indigenous peoples during colonization from the perspective of the people who experienced and fought it (rather than westward expansion and nation building).

As teachers, we can begin to make room for counternarratives by learning about multiple ways of knowing, multiple ways of demonstrating knowledge, and the many varied understandings of what knowledge is important to a community. Can you think of a local issue in your community and how different sides of the issue might be presented? Furthermore, how might an educator present such an issue, in a way that allows students to critically think about the issue?

6.3 Instructional Strategies and Approaches

There are multiple ways to deliver instruction and their degree of success varies based on both the strategy implemented and the needs, background, preferences and readiness of the learner. Education researcher and professor John Hattie spent more than 15 years reviewing studies on what impacts student learning outcomes. After reviewing over 1,200 studies he identified 7 major sources that contribute to learning; the student, the home, the school, the curricula, the teacher,teaching and learning approaches, and the classroom (John Hattie, 2012).

This visual to the left includes some of the many variables Hattie reviewed while conducting his meta analysis of education research. Hattie found that .4 was the average effect or impact size of the various interventions he studied. Thus, strategies that yield above .4, on the right hand, teal colored section of the graphic, are considered more successful in leading to student progress. The higher the effect size, the greater the positive impact on learning. A larger, more comprehensive list of strategies that impact learning can be found in his publications. You will find elements of some of these strategies within the common instructional approaches that follow.

Direct Instruction

In general usage, the term direct instruction refers to (1) instructional approaches that are structured, sequenced, and led by teachers, and/or (2) the presentation of academic content to students by teachers, such as in a lecture or demonstration. In other words, teachers are “directing” the instructional process or instruction is being “directed” at students.

The basic techniques of direct instruction not only extend beyond lecturing, presenting, or demonstrating, but many are considered to be foundational to effective teaching. For example:

- Establishing learning objectives for lessons, activities, and projects, and then making sure that students understand the goals.

- Purposefully organizing and sequencing a series of lessons, projects, and assignments that move students toward understanding and the achievement of specific academic goals.

- Reviewing instructions for an activity or modeling a process—such as a scientific experiment—so that students know what they are expected to do.

- Providing students with clear explanations, descriptions, and illustrations of the knowledge and skills being taught.

- Asking questions to make sure of student understanding after a lesson.

As seen in Image 6.3, teachers rarely use either direct instruction or some other teaching approach—in practice, diverse strategies are frequently blended together. For these reasons, negative perceptions of direct instruction likely result more from a widespread overreliance on the approach, and from the tendency to view it as an either/or option, rather than from its inherent value to the instructional process (Carnine, Silbert, Kameenui, & Tarver, 1997).

Active Learning

The Socratic method, originally formulated by the Greek Philosopher Socrates in 399 BCE, is a teaching method where the instructor asks questions designed to understand the point of view of the students. This was a radical approach for its time because it placed the learning more in the hands of the student. Teachers have been using this method for centuries and it has taken many forms but the intent was always to critically engage students in the learning. As active learners, students are motivated to ask questions and make sense of what they are learning. All students have the opportunity to reflect on a prompt, work in a pair or small group, and interact with the material. Active learners are asking questions, conversing about a topic and interacting with others to learn.

Drill and Practice

The drill and practice instructional strategy refers to small tasks, such as the memorization of spelling and vocabulary words, or the practicing of the multiplication tables repeatedly. As students, drill and practice instruction was probably a familiar memory throughout your schooling. It is used primarily for students to master fundamental materials, typically limited to declarative knowledge, through repetition. By today’s educational standards, drill and practice is considered outdated and often deemed ineffective as an instructional strategy. According to Jill Sunday Bartoli, “Having to spend long periods of time on repetitive tasks is a sign that learning is not taking place — that this is not a productive learning situation.” (Bartoli, 1989, p. 292)

Lecture

Lecture is a convenient instructional strategy. Material can be delivered efficiently since there are no interruptions from students. A lecture can allow the teacher to relate new material to other topics in the course, define and explain key terms, and relate material to students’ interests. It is one type of direct instruction.

Lecture is an instructional strategy that places students in a passive role. Essentially the lecturer is the expert and the students are having knowledge, declarative or procedural, poured into their brains. The material and presentation are solely the intellectual product of the teacher. Students sit silently at desks that face the lecturer, sometimes taking notes. Some lectures may include visuals such as PowerPoint presentations.

Often lecture topics are not remembered well because retrieval pathways to memory have not been established by students actively participating in the instruction. Students don’t typically have the opportunity to take the presented material and create their own meaning. The lecturer usually does not know if students understand the topic because there is no feedback from students (Lujan, H. & DiCarlo, S, 2006).

Question and Answer

The technique of question and answer allows the application of knowledge by students and offers some opportunity for participation. By asking questions, teachers are inviting brief responses from students, who incorporate their prior knowledge and some interpretation in their responses. This gives some indication of whether students are understanding the material being presented. Questions serve both to motivate students to listen and to assess how much and how well they are learning the material. Incorporating this instructional approach allows both the teacher to ask students questions and students to ask the teacher questions, fostering a better understanding of the lesson (Paul & Elder, 2007).

Discussion

In this instructional strategy, the role of the teacher shifts to leading an exchange of ideas about a specific topic. The teacher is no longer the sole provider of the content as students gain a voice for their ideas and sometimes the research they have conducted. At times, the teacher may assign students’ individual concepts to speak about during the discussion. Some control of the course the discussion takes depends on the students. All of the content planned for the lesson might not be discussed. In fact, after reflecting on the day’s discussion a teacher might begin the next day with important content that had been overlooked or dismissed during the discussion.

In order to ensure equitable discussions, teachers need to incorporate strategies so all students contribute to the conversion and all student voices are heard. In addition, for effective class discussions students need to listen to what their classmates are saying in order to consider multiple perspectives, consider new ideas, and sometimes revise their own thinking. It’s helpful for all when the teacher, or better yet, a student, summarizes the important points (Brookfeld & Preskill, 2012).

An example of a type of discussion you may have experienced in middle or high school is a Socratic seminar. A Socratic seminar is a formal discussion, usually based on a piece of text, in which the leader, who may initially be the teacher but should eventually be a student, asks open-ended questions. Teachers often ask that students support their ideas with evidence from the text and/or their personal experiences. Students listen closely to the comments of others, think critically for themselves, and express their own thoughts in response to the ideas of their peers (Israel, 2002).

If you would like to design a socratic seminar, please watch the following video:

Video 6.2

Think Aloud

Thinking aloud makes the invisible visible. When students think aloud they allow their teachers and peers to follow their reasoning. This strategy is commonly used when solving math problems or trying to comprehend a challenging reading passage but it can be applied to any content area. Effective teachers model thinking aloud frequently with their students to demonstrate how they might approach difficult math problems, approach complex text, and engage with cognitively demanding concepts.

Teachers can verbalize their questions and wonderings as they think aloud so that students can see that problem solving is not a simple, linear process. By modeling this process of Thinking out loud students can verbalize their inner speech and this outward verbalization can direct future problem-solving. Think-alouds can be used to model comprehension processes such as predicting, creating mental images, connecting new information to prior knowledge, monitoring comprehension, and applying steps in a sequence. (Farr & Conner, 2015) When students think aloud they learn how their own learning works and the teacher has the opportunity to informally assess the depth of their understanding or the types of misconceptions they might hold. This cyclical process allows the teacher to modify future instruction based on what students reveal as they think aloud.

Video 6.3

Inquiry

When students investigate so they can answer a question about a particular topic, they are using inquiry or inquiry-based learning. When teachers use inquiry-based learning, students or teachers may identify questions. The questions posed should be open ended so the learner has space to hypothesize and inquire about the topic. Inquiry learning may be experienced individually; but it is beneficial when students work with other students. Differing perspectives and varied resources are important to inquiry-based projects.

Providing responses to questions such as “Why is the sky blue?” demands high-order thinking skills from both the student and the teacher. Allowing students to explore a broad topic or to choose questions of interest creates a level of investment and lays the foundation for an environment for successful inquiry-based projects. Students benefit from learning and negotiating through group investigation in order to answer a question.

Teachers who wish to engage in inquiry-based learning must set the stage for this process in three ways:

- Assess students to determine their knowledge of the topic, and lay groundwork when that knowledge does not exist.

- Match the scope of the inquiry question to the learning level of students.

- Provide resources and/or provide internet search strategies for locating credible resources that will inform the inquiry.

The teacher’s role in inquiry-based learning is one of facilitator, mentor and advisor. Students may struggle through problems; however, if the struggle occurs at a level that students may be successful, this struggle is worthwhile. The teacher’s most difficult role, in this case, is to resist answering questions that would inform the inquiry and allow students to experience productive struggle.

“Productive struggle is the “sweet spot” in between scaffolding and support. Learning happens when students stretch beyond their comfort zone. Rather than immediately helping students at the first sign of distress, we should allow them to work through these stretch zones independently before we offer assistance.

That may sound counterintuitive, since many of us assume that helping students learn means protecting them from negative feelings of frustration. But for students to become independent learners, they must learn to persist in the face of challenge.” (Barbara Blackburn, 2018, p.1)

Inquiry based learning requires time and patience; however this teaching strategy lays groundwork for real-world learning in which students will engage in throughout their lives (Sharples, Collins, Feißt, Gaved, Mulholland, Paxton, & Wright, 2011).

Project Based Learning

Project-based learning is an approach that gives students the opportunity to develop knowledge and skills through engaging projects set around challenges and problems they may face in the real world. In project-based learning (PBL), there is often a “public product” that becomes a culminating event at the end of a project and allows students to showcase their learning. It is a natural extension of inquiry learning. “Effective PBL requires students to engage in sustained inquiry, observation, and hopefully fieldwork to help them develop into advocates for causes they’re exploring.” (Jorge Valenzuela, 2021)

Four major concepts form the foundation of project based learning; active construction, situated learning, social interactions, and cognitive tools. Active construction refers to learners actively constructing meaning based on their experiences and interactions with the world rather than being passive recipients of learning. It’s based on situated learning because it occurs in an authentic, real-world context that can directly involve students and it includes ongoing opportunities for social interaction during the learning through discussions and sharing of ideas in the classroom. Lastly, PBL incorporates the use of cognitive tools such as organizers, data displays, software, and presentation resources that support student learning. (Krajcik & Blumenfeld, 2014)

When done well, PBL inspires students to question, think critically, and draw connections between their learning and the real world. The model of project based learning can vary from one school to the next or even from one project to another, however, the following critical elements are always present:

- Organization around an open-ended driving question or challenge

- Integration of essential abstract academic content and skills into the project development

- Use of inquiry to learn or create something new

- Application of critical thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, and communication ( “21st-century skills”)

- Student voice and choice

- Opportunities for feedback and revision

- Presentation of the problem, process, and final project

An example of Project Based Learning – video clip

Video 6.4

Community Based Learning

Community Based Learning(CBL) is a “broad set of teaching/learning strategies that enable youth and adults to learn what they want to learn from any segment of the community.an approach that gives students the opportunity to learn through engagement with community.” At its best, Community-Based Learning integrates community engagement, school-community partnerships, and critical social-justice based reflection to meet the learning needs of the students while reciprocally supporting the needs of community partners. When taught with intention, the engagement inherent in Community Based Learning works to create an environment full of potential for students and community partners to improve the world around them by expanding the classroom into the world outside of the school grounds.

Community Based Learning can take the following forms of curricular involvement:

- Direct Service: cleaning up litter on a beach or serving food in a soup kitchen

- Indirect Service: fundraising or gathering signatures for a petition

- Apprenticeships: volunteering while learning a trade

Video 6.5

Check out this inspiring CBL project: “Service Learning and The Power of One”

Collaborative Learning

“Collaborative learning” encompasses a range of approaches that involve students in joint intellectual efforts or in the efforts of students and teachers together. Working in groups of two or more, students work to gain understanding, develop solutions, or create a product. Most collaborative learning activities center on students’ exploration or application of the course material rather than relying simply on the teacher’s presentation of it. It is a significant shift away from the typical teacher centered or lecture-centered classroom. (Smith & MacGregor, 1992)

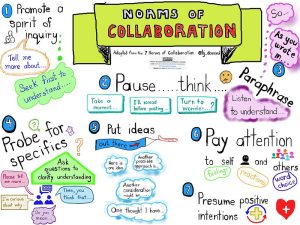

It is based on the assumptions that learning is an active, constructive process that depends on rich contexts. Collaborative learning also recognizes that learners are diverse and that learning is inherently social. As Jeff Golub explains, “Collaborative learning has as its main feature a structure that allows for student talk: students are supposed to talk with each other….and it is in this talking that much of the learning occurs.” (Golub, 1988) Collaborative learning produces intellectual synergy through mutual exploration, meaning-making, and feedback. It often leads to deeper understanding and sometimes a whole new understanding for students. The image below outlines an example of a process to promote collaboration in the classroom. It involves student conversation prompts to encourage them to ask questions. This process also enables them to listen and then summarize the statements of other classmates so they can come to an understanding and work together as they learn.

The most structured example of collaborative learning is cooperative learning. In cooperative learning, the development of interpersonal skills is as important as the learning of content itself. Many cooperative learning tasks include both academic and social skills as objectives. Strategies often involve assigning roles within each small group (such as recorder, participation encourager, summarizer) to ensure the positive interdependence of group members and to enable students to practice different skills. Setting aside time for students to reflect on how they are doing and on the group process is embedded within the approach so that students become more effective working in future groups. (Johnson, Johnson and Holubec, 1990).

Cooperative learning’s emphasis on social skills aligns well with the current educational focus on social emotional learning (SEL) in the classroom. The relationship skills developed by working interdependently in groups address a component of one of the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) framework’s key elements of SEL. When teachers design collaborative learning thoughtfully, including intentional grouping, clear guidelines for interacting and expectations for outcomes, students develop active listening, clear communication, negotiation skills, and the ability to work with diverse individuals.

6.4 Creating Learning Goals

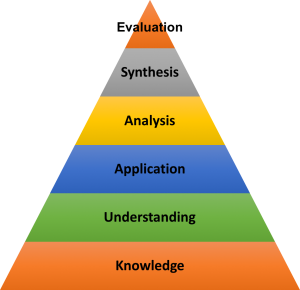

Teaching is a complex endeavor and many tools have been developed to organize instruction and ensure lessons are purposeful and lead all students to learn. Benjamin Bloom (mentioned earlier) created a hierarchical classification of thinking that has been used for classroom instruction. It relies on a continuum of cognitive complexity from simple to complex and concrete to abstract (Armstrong, 2010). It is a commonly used resource for writing objectives with verbs classified by level. The verbs at the top of the pyramid (Image 6.4) are believed to represent higher-order thinking skills while the ones at the bottom are more basic.

Bloom’s taxonomy underwent a major revision by Krathwohl & Anderson (2001). Image 6.9 names the various levels of Blooms Taxonomy. The pyramid begins with Knowledge and increases the cognitive load of the learner. The verbs associated with differing levels of thinking skills required for any given task provide guidance as a teacher writes lesson outcomes for a class. For instance, a lower order outcome may be: The student will recall multiplication tables one through four. A higher order outcome might be: The student will differentiate between nutritious foods and foods with processed ingredients. When teachers understand the complexity of thinking levels required by the lesson, they may ensure that students have a good balance amongst all skills in the spectrum.

Focusing on what students should know is frequently called the “cognitive” approach; focusing on what students should be able to do is known as the “behavioral” approach.” Most teachers often combine the two and include both declarative and procedural knowledge within their objectives. Large-scale learning objectives will be articulated in a teacher’s curriculum guide, but it is up to each individual teacher to formulate learning objectives for individual lesson plans.

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy for Creating Learning Objectives

Oregon provides guidance for developing learning goals for students based on students’ current abilities and baselines skills and in alignment to the Oregon state standards (Oregon Department of Education). Teachers, often working in grade level teams or professional learning communities (PLCs), develop objectives to guide their day to day teaching. They check for understanding using observations, exit tickets, or work samples to determine if students are learning and they adjust their teaching accordingly to support student progress (Fisher & Frey, 2014). This may include reteaching parts of the lesson, differentiating instruction for groups of students, providing additional practice opportunities, or moving quickly through a concept that seems to already have been grasped by students.

Lesson plans often include 2 or 3 objectives. This allows the teacher to scaffold instruction, providing lots of support when introducing a concept and then scaling back support to encourage student independence, based on the work of Lev Vygotsky (Wood, Bruner, and Ross, 1976). Students bring varying levels of readiness to learn a concept or complete a task. If teachers offer support to students during the learning process, they can assist them in accessing more complex tasks. Using Bloom’s Taxonomy can help teachers create objectives that start with tasks requiring lower order thinking skills, and move to tasks that require higher order thinking. By including multiple objectives in progression, a teacher can measure what objective the students have not met yet and focus on addressing those specific parts of the lesson.

Critique of Bloom’s Taxonomy

Both Bloom’s Taxonomy and its 2001 revision tend to meet the needs of bureaucratized institutional teaching systems. Public education in the US is trending towards creating distinct, measurable outcomes to demonstrate student learning. Bloom’s taxonomy gives educators a relatively straightforward framework to accomplish these goals.

However, the progression of Bloom’s Taxonomy through hierarchical levels is rigid and is not representative of the way many people learn. The taxonomy directs educators toward its “ top” level at the risk of devaluing the other levels. The distinction between the categories is artificial since any learning involves many processes. The classification of learning into discrete levels may undermine the holistic, interrelated, and interdependent nature of the levels that Bloom’s Taxonomy attempts to capture. (Fadul, J. A. (2009).

“Collective Learning: Applying distributed cognition for collective intelligence”. The International Journal of Learning. 16 (4): 211–220.) Further, from the perspective of this counter narrative, its rigidity does not leave much room for cultural inclusivity.

You may wonder why and how critiques emerge about well established concepts like Bloom’s Taxonomy. One avenue of critique arises from the realm of critical theory. Critical theorists attempt to understand and dismantle the societal frameworks that cause and contribute to oppression. Critical theorists assert that academia itself has played a role in perpetuating these oppressions, and advocate for reimagining the status quo. One way to support this kind of inquiry is to learn about different educational systems around the world. It can give us ideas and fresh perspectives. Another reason is that comparing outside or nondominant systems to our own highlights the assets and deficits that might be invisible to us because we are so immersed in the environment. You will learn more about this as you progress through your studies to become a teacher.

Consider

After reading about Bloom’s Taxonomy, its critiques, and how objective writing can be approached, what questions or critiques do you have about the following sample learning objectives? For example, critiquing some of the following objectives would involve a teacher asking themselves: is this really what we want students to learn? Why 85%? Why do we care? Is this valuable in the big scheme?

Sample Objectives

Remember: The student will be able to list the parts of a salmon with 85% accuracy.

Understand: The student will be able to paraphrase research on the effectiveness of vaccination policies with 85% accuracy.

Apply : The student will be able to create a graph of emissions of greenhouse gasses over time with 85% accuracy.

Analyze: The student will be able to explain the various ways to solve a math equation with 85% accuracy.

Evaluate: The student will be able to evaluate the effectiveness of U.S. propaganda during WWII with 85%.

Create: The student will be able to construct a program for addressing food disaster relief with 85% accuracy.

Conclusion

You may be familiar with the slogan “knowledge is power.” There’s a lot of truth to that statement. You may also be familiar with the saying: “the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world.” As teachers, we have the power to shape not only what our students learn, but what our students learn is important, and how they learn those things. Reflection on this dynamic can give us the opportunity to consider how to introduce ways of teaching and learning that have been devalued and erased from mainstream education through the process of colonization and homogenization of the curriculum. In order to do this, teachers must be in touch with the communities they teach, and the historical and political forces that have brought us to where we are today.

References

Alber, R. (2014). Six scaffolding strategies to use with your students. Edutopia. Retrieved on 4/29/19 from www.edutopia.org/blog/ scaffolding-lessons-six-strategies-rebecca-alber

Arend, B. & Davis, J. (n.d.). Seven ways of learning: A resource for more purposeful, efective, and enjoyable college teaching. Retrieved 3/5/19 from sevenwaysofearning.com/the-seven-ways/learning-with-mental-models.

Bartoli, J. S. (1989). An ecological response to Coles’s interactivity alternative. Journal of learning Disabilities, 22(5), 292-297.

Blatchford, P., Kutnick, P., Baines, E., & Galton, M. (2003). Toward a social pedagogy of classroom group work. International Journal of Educational Research, 39(1-2), 153-172.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. New York: McKay, 20-24.

Brookfeld, S. D., & Preskill, S. (2012). Discussion as a way of teaching: Tools and techniques for democratic classrooms. John Wiley & Sons.

Carnine, D., Silbert, J., Kameenui, E. J., & Tarver, S. G. (1997). Direct instruction reading. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

Elmore, T. (2019). Six Simple Ways to Better Engage Generation Z. Growing Leaders Retrieved from https://growingleaders.com/ blog/six-simple-ways-engage-generation-z/

Finch, J. (2015). What is Generation Z and What Does it Want? Fast Company. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/ 3045317/what-is-generation-z-and-what-does-it-want

Giroux, H. A. (2013). America’s education deficit and the war on youth: Reform beyond electoral politics. NYU Press.

Heck, T. (2018). What is Bloom’s taxonomy? A definition for teachers. Retrieved 3/5/19 from www.teachthought.com/learning/ what-is-blooms-taxonomy-a-definition-for-teachers.

Knowledge How (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). (2021, April 20). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/knowledge-how/

Krathwohl, D. & Anderson, L. (2009). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Mayer, R. E. (2004). Should there be a three-strike rule against pure discovery learning?: The case for guided methods of instruction. American Psychologist, 59(1), 14-19.

New York State Education Department. (2018). New York State Social and Emotional Learning Benchmarks. Retrieved from: http://www.p12.nysed.gov/sss/documents/NYSSELBenchmarks.pdf

Owens, T. R., & Wang, C. (1996). Community-Based Learning: A Foundation for Meaningful Educational Reform. School Improvement Research Series. https://educationnorthwest.org/sites/default/files/Community-BasedLearning.pdf

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2007). Critical thinking: The art of Socratic questioning. Journal of developmental education, 31(1), 36.

Saks, K., Ilves, H., & Noppel, A. (2021). The impact of procedural knowledge on the formation of declarative knowledge: How accomplishing activities designed for developing learning skills impacts teachers’ knowledge of learning skills. Education Sciences, 11(10), 598.

Sharples, M., Collins, T., Feißt, M., Gaved, M., Mulholland, P., Paxton, M., & Wright, M. (2011, June). A “laboratory of knowledge- making” for personal inquiry learning. In International Conference on Artifcial Intelligence in Education (pp. 312-319). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

The glossary of education reform. (n.d.). The Glossary of Education Reform. http://edglossary.org/

Ültanır, E. (2012). An epistemological glance at the constructivist approach: Constructivist learning in Dewey, Piaget, and Montessori. International Journal of Instruction, 5(2).

Van Joolingen, W. R. (2000, June). Designing for collaborative discovery learning. In International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems (pp. 202-211). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

View of Indigenous knowledge and research: The míkiwáhp as a symbol for reclaiming our knowledge and ways of knowing. (n.d.). https://fpcfr.com/index.php/FPCFR/article/view/26/64

Images

6.1 “Tiles inside the Jame Mosque of Yazd” by Creative Commons, Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain, CC

6.2 “Writing-Hand-Pen” by pxhere is licensed under CC BY 4.0

6.3 “John Hattie” by Mikel Agirregabiria, flickr is licensed under CC BY 4.0

6.4 “Hands-on STEM” by Octaviano Merecias-Cuevas, Oregon State University is in the Public Domain, CC0

6.5 “Student doing her homework” by Polina Tankilevitch, Pexels is licensed under CC BY 4.0

6.6 “Blackboard Teacher” by pxhere is in the Public Domain, CC0

6.7 “Step out of comfort zone concept” by Marco Verch, Flickr is licensed under CC BY 4.0

6.8 “Norms of Collaboration” by Helen DeWaard, flickr is licensed under CC BY 4.0

6.9 “Blooms-pyramid” by Bnummer, Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Videos

6.1 “Declarative and Procedural Knowledge” by Hidayah Nadzri, youtube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

6.2 “How to Design a Socratic Seminar” by John Spencer, John Spencer, Spencer Education is in the Public Domain, CC0

6.3 “Think Aloud” by youtube, Citizens Academy Cleveland is licensed under CC BY 4.0

6.4 “March Through Nashville Project” by Buck Institute for Education is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

6.5 “Community-Based Learning: Connecting Students With Their World” by youtube, Edutopia is licensed under CC BY 4.0

6.6 “Service Learning and the Power of One” by Tedx Talks is licensed under CC BY 4.0