7 Curriculum and Academic Standards

“If we start with Blackness (which we have not traditionally done in schooling) or the group of people who have uniquely survived the harshest oppressions in this country, then we begin to understand ways to get literacy education right for all”

Gholdy Muhammad, 2020

Learning Objectives

- Define the purpose of a curriculum

- Examine the sociological influences of the four curricula within the context of today’s politicized society

- Examine the cognitive and affective domains of curricula

- Identify equity-focused practices regarding curricular approaches, pedagogy and classroom community

Curriculum, according to John Dewey (1902) “…is a continuous reconstruction, moving from the child’s present experience out into that represented by the organized bodies of truth that we call studies… are themselves experience…” (p. 11–12). This chapter will focus on the different types of curricula and the relationship between curricula, cognition, and affect.

7.1 The Purpose of a Curriculum

What is the importance of a curriculum? Answers will vary. According to the United States Department of Education the purpose of having a curriculum is to provide teachers with an outline for what should be taught in classrooms. The United States Department of Education wants to ensure that students are exposed to rigorous curricular goals to ensure that they are prepared for real-world experiences that will make students college and career ready. Most schools look to local or state authorities for guidance regarding a curriculum.

Most countries of the world have unified standards and a central curriculum. The United States, however, has never had a unified curriculum or even standards until attempts were made through federal legislation such as No Child Left Behind and the state-led initiative called the Common Core. This is because education started as a local affair in the United States. Core Knowledge Pioneer E.D. Hirsch argued that all children in the United States should have foundational essential knowledge, especially in grades K-8. This issue has been debated for hundreds of years in the United States due to the differing agendas of federal, state and local governments and different philosophies regarding the purpose of education. Local communities want a say in what is taught in their local schools, especially of late, controversial themes such as evolution, racism, climate change, amongst other hot topics. Education is indeed highly politicized today.

There is immense power in determining what students will learn, with many competing forces at play. Because schooling in the United States is left to the jurisdiction of individual states, certain content is viewed, valued, and taught differently depending on the collective values of the state or county. While school districts provide a curriculum, teachers will pick and choose what they focus on. Teachers have more power that some might think. Once the classroom door is closed, teachers teach largely based on who they are and what they believe in- even as they use a district curriculum. There are many ways to teach about Martin Luther King, for example. One teacher might focus on how much progress has been made in terms of racial justice, while another teacher will focus on the lack of racial justice. Imagine how different learning could be if more complex and important details were a part of the curriculum for all students.

But, what is the curriculum that each U.S. state follows? In 1990 a movement began in the United States to establish national educational standards for students across the country. The goals were (a) outlining what students were expected to know and do at each grade level and (b) implementing ways to find out if they were meeting those standards. Currently 41 states and the District of Columbia have adopted the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). The four states that never adopted the Standards are Virginia, Texas, Alaska, and Nebraska and the four states who have successfully withdrawn from the Common Core curriculum are Arizona, Oklahoma, Indiana, and South Carolina. The states who have not adopted the CCSS have the responsibility to review their academic standard on an ongoing basis to provide quality education to their students. Wikipedia

Who influences which curriculum is chosen? What is their agenda? Do they always have the best interests of students in mind? Who do you think should decide?

| Parents

and Community Members |

Parents are the taxpayers in the district, so they have a vested interest in the way their children are taught. Do all parents/caregivers understand how the educational system works? Do some parent groups have more power than others based on things like socioeconomic status? |

| Special Interest Groups | Special interest groups advocate for particular policies and focus on education. These groups can be composed of people from a specific culture, ethnicity, or religious group and may lobby for changes in education through a political lens based on their political party affiliation. |

| State Legislatures | State legislatures play a vital role in education because they set the state budget for education and pass laws pertaining to the educational system statewide. Some policies are influenced by state legislators and the state’s department of education.State legislators tend to focus on what best meets the needs of all students but could be influenced by politicized lobbyists and groups. |

| Textbooks and

Testing Companies |

The states that represent the greatest possible business for the publishers can have tremendous influence over which curriculum is used. |

| Teachers | Teachers can lobby for particular types of curricula. They are likely the most expert regarding the curriculum -but not necessarily without personal bias or agendas. |

| School Boards | School boards are composed of elected volunteers and they are often in the position of making decisions regarding curriculum choices. |

7.2 Sociological Influences of the Four Curricula

There are four different types of curricula that educators have to address in the classroom; these four are the explicit, implicit, null, and extracurricular. The most obvious curriculum in the classroom is the explicit curriculum because that is the curriculum that has been approved by each state. The extracurricular curriculum also exists for such activities as academic clubs, band and chorus, or sports. The curriculum that is not so obvious is the implicit curriculum or hidden curriculum which teaches things not explicitly stated, and the null curriculum is information that students may never be exposed to because they are completely excluded from the explicit curriculum. Each of these curricula will be explained below with examples to illustrate what each entails.

Explicit Curriculum

Explicit instruction is a curriculum that has been intentionally designed, field tested by educators, and disseminated publicly, often with resources that will help teachers facilitate classroom instruction. A curriculum is guided by standards. It is important to differentiate between standards and curriculum:

While NY has an organized statewide digital curriculum that all educators can access, Oregon has adopted the same Common Core state standards but does not have a statewide curriculum. Instead, Oregon has district curricula which follow the Common Core standards ( see video 7.2 for more information about the Common Core Movement). What are the advantages of a system such as the system in New York? They are able to share curriculum, ideas, and lesson plans across districts. This makes a difference when some districts have access to a lot more resources than others. When teachers in a district can only share within its district, there is a limit to what they can achieve. For example, If a district just started a dual immersion program and no one else has such a program, they have to start from scratch and work alone, whereas in a statewide approach, resources are widely shared.

Implicit Curriculum (also known as the Hidden Curriculum)

The implicit curriculum involves hidden lessons that emerge from the culture of the local school district school and the values, behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs that have been defined by the district. Bruner (1960) addressed the need to cultivate an understanding of ideas by including content beyond the explicit curriculum. An example of an implicit curriculum is character education. Character education may address values that are not part of the state-approved curriculum. While character education can be found in the explicit curriculum, the nuances of the character education program may be informed by many factors present in the local school district including the school community’s cultural expectations, values, and perspectives. A character education program may also include specific curricular topics which may contain varying ideological and/or cultural messages. Teaching strategies that connect the school to the community like problem-based learning or applied learning, can also be part of the implicit curriculum.

Pause and Ponder – Hidden Curriculum

Everything that goes on in school that is not part of an official lesson is part of the hidden curriculum. What messages do schools and teachers send by

- requiring students to walk in a line?

- having students ask permission to use the restroom?

- creating contests in the classroom based on individuals’ achievements rather than mutually beneficial collaborative partnerships?

- having same-age groupings in classes vs mixed-age groupings?

It is important that schools and educators consider that all schools have a hidden curriculum, and that it is largely outside of our consciousness. With attention and reflection, this curriculum can be brought into sharper focus. In the late 1970s, Jean Anyon did a study of different kinds of schools in the United States and described her observations about socioeconomic class and how SE class is perpetuated by a kind of hidden curriculum. She observed that schools in wealthier communities provided more autonomy and freedom to their students thus encouraging students towards executive and leadership roles, while students in poorer communities were given less autonomy and freedom, and subsequently encouraged towards more working and middle class roles. Ultimately, Anyon concluded that students were being prepared for certain kinds of work, in her words: “differing curricular, pedagogical, and pupil evaluation practices emphasize different cognitive and behavioral skills in each social setting and thus contribute to the development in the children of certain potential relationships to physical and symbolic capital, to authority, and to the process of work” (Anyon, 1970)

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded a survey of U.S. public school teachers’ from 2010 to 2012 in both English language arts and math classes in seven large metropolitan areas. The study examined teaching-effectiveness or differences in classrooms taught by the same teacher; and whether factors such as student demographics play a role. The study found that “whenever there was a classroom of predominantly students of color, teachers were systematically less likely to use proven instructional models they used with White students.”

The fact that low income students, students of color and underserved emergent bilinguals, routinely receive less instruction in higher order skills development than other students is evident in our educational system. The curriculum is typically less challenging and more repetitive, with teachers reinforcing what they believe students should be able to do on specific tasks and focusing on the lower skills in Bloom’s Taxonomy. This type of instruction denies students the opportunity to engage in what neuroscientists call a productive struggle that actually grows our brain. As a result, a disproportionate number of culturally and linguistically diverse students are dependent learners.

Zaretta Hammond, in her book Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain (2015), explains what neuroscientists are talking about neuroplasticity with an emphasis on culture. She states that we, as future educators, spend a lot of our time learning about different theories but do not learn how to apply them in our everyday teaching. Her emphasis has been on linking the research about the brain and how it can be applied to a culturally responsive pedagogy. ”Cognition and higher order thinking have always been at the center of culturally responsive teaching, which makes it a natural partner for neuroscience in the classroom” (Zaretta Hammon, p. 4). Therefore, we need to strive to facilitate student’s cognitive growth so that they can activate their neuroplasticity and become independent learners.

In the table below, you will find the difference between a dependent learner and independent learner according to Zaretta Hammond (p.

| The Dependent Learner | The Independent Learner |

| Is dependent on the teacher to carry most of the cognitive load of a task | Relies on the teacher to carry some of the cognitive load temporarily |

| Is unsure of how to tackle a new task | Utilizes startegies and processes for tracking a new task |

| Cannot complete a task without scaffolds | Regularly attempts new tasks without scaffolds |

| Will sit passively and wait if stuck until teacher intervenes | Has cognitive strategies for getting unstuck |

| Doesn’t retain information well or “doesn’t get it” | Has learned how to retrieve information from long-term memory |

Teachers who understand the power of the hidden curriculum recognize their potential to develop the social emotional capacities of their students, and realize that taking time to develop the social emotional needs of their students can have life-changing consequences. Creating independent students with leadership capabilities will have a significant effect on their lives, as Hammond and Anyon point out. The hidden curriculum can be a double-edged sword with positive or negative implications for students. There are many teachers who don’t necessarily recognize their own cultural frameworks and how they influence the hidden curriculum they are teaching or perpetuating. Understanding one’s own cultural influences is critical for all teachers and should be required professional development for any current or future educators.

Deeper Dive – Jean Anyon

Jean Anyon’s foundational article on how The Hidden Curriculum can transmit ideas about social class:

Null Curriculum

Eisner (1985) defined null curriculum as information that schools do not teach:“… the options students are not afforded, the perspectives they may never know about, much less be able to use, the concepts and skills that are not part of their intellectual repertoire” (Eisner,1985, p. 107).

There are several examples of null curriculum that can be identified in content areas. For example, in social studies, the teacher may give a general overview of the Oregon Trail in terms of westward progress, but leave out the impact on native peoples. Another example would be the exclusion of Darwin’s theory of evolution from the official biology curriculum. Null content may represent specific facts omitted in a particular unit of study. An example of this would be a social studies unit focusing on the New Deal may not reference the fact that the New Deal failed to resolve the problem of unemployment. Many educators would argue that racism has not been taught in US schools for most of the history of the United States, and recent attempts to rectify this have resulted in huge controversy.

Extra-Curricular Curriculum

Extra-curricular curriculum includes school-sponsored opportunities that fall outside of academic requirements prescribed on the local and state levels. Examples of extracurricular activities include participation in sports, music, student governance, yearbook, school newspaper, and academic clubs. Extracurricular participation is a strategy to promote school connectedness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Extracurricular activities are often associated with many positive outcomes such as higher academic achievement and decreased school dropout (Farb & Matjasko, 2012).

According to the United States National Center for Education Statistics (2012), sports are the most common type of extracurricular activity among secondary school students, with 44% of high school seniors reporting participation in some type of sport. Additionally, 21% of students participate in music activities, as well as clubs, such as academic (21%), hobby (12%), and vocational clubs (16%).

7.3 Racial Justice in the Curriculum

Recent concerns and protests about racial justice in the United States are another example of the tensions among explicit, implicit, and null curricula. Some schools may openly address and discuss protests for racial justice, while other schools may not mention them at all. The reasons for not addressing this topic range from not wanting to upset students or parents to openly racist thinking at the classroom, district, or state level. However, if something is never mentioned in school and therefore becomes part of the null curriculum, students take note of what is missing. Milner (2017) describes events like the violence in Charlottesville in 2017 as exactly the kind of topic that students must learn about in schools to cement the importance of social justice for future generations. Another example is Critical Race Theory. CRT seeks to address institutional and systemic racism and how certain ethnic groups historically have not had access to the same opportunities in housing, healthcare, justice, education, leading to an inequitable society. Critical Race Theory has become a hotly contested theory reflecting a very divided politicized US society, so much so that conservative legislators are taking steps to remove CRT from the classroom. All educators need to to understand how racism has functioned in US society and what is the lens through which they will approach the topic. Following the death of George Floyd, we are in a time of awakening and social changes in the United States, and educators most certainly have an important role to play.

Video 7.1

This article and video describe a proposed 2023 bill backed by Governor Ron DeSantis proposes to prevent Florida public schools from “making people feel “discomfort” or “guilt” based on their race, sex or national origin.”

Critical Lens – Curriculum in the News

- DeSantis defends blocking African American studies course in Florida schools

- Ron DeSantis’s war on “woke” in Florida schools, explained

How much should the courts and the government control what goes on in the classroom

7.4 Cognitive and Affective Domains of Curricula

The curriculum can be viewed from varying perspectives. The cognitive perspective of the curriculum focuses primarily on the acquisition of knowledge. The affective perspective tends to go beyond the acquisition of knowledge to include the degree that students value the knowledge that is being delivered to achieve educational outcomes. These two perspectives of curricula allow people to consider not only the subject matter, but how the students react to the material being delivered.

The Cognitive Domain of Curricula

The cognitive domain of curricula deals with how students gain knowledge. In today’s schools, this is often achieved by dividing the knowledge into separate content areas. This model prioritizes a content-specific instructional focus over social emotional learning.

Subject-Centered

The idea of subject-centered instruction separates instruction into distinct content areas. The skills and content contributing to the curriculum varies by subject. While this model was adopted in the United States in the 1870’s, it is still in practice today, especially at the secondary level. The pros and cons of this model were outlined by Ornstein (1982).

| Pros of subject-centered Instruction | Cons of subject-centered instruction |

| Subjects are a logical way to organize and interpret learning. | The curriculum is fragmented, and concepts learned in isolation. |

| Such organization makes it easier for people to remember information for future use. | The curriculum is fragmented, and concepts learned in isolation. |

| Teachers (in secondary schools, at least) are trained as subject-matter specialists. | It deemphasizes life experiences and fails to consider the needs, interests and cultures of students. |

| Textbooks and other teaching materials are usually organized by subject. | The teacher dominates the lesson, allowing little student input |

| Textbooks are not culturally responsive and usually include just one point of view | |

| The emphasis is on using lower-order thinking skills like teaching of knowledge, and the recall of facts. |

Common Core Curriculum

The Common Core movement emerged in the early 2000s as a response to concerns about the variability and inconsistency in educational standards across different states. The idea was to establish a set of uniform, rigorous standards that would ensure all students were adequately prepared for college and the workforce, regardless of where they lived. The National Governors Association (NGA) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) led the effort, bringing together educators, researchers, and experts to develop the Common Core State Standards. The standards were released in 2010 and initially adopted by 45 states and the District of Columbia. E. D Hirsch, who founded the Common Core movement, advocates for a core curriculum where all students should know a common body of knowledge. This model takes a more interdisciplinary approach to ensure that all prescribed content is covered.

Video 7.3

Opponents of this method argue that this approach doesn’t take children’s unique learning styles into consideration. For example, children with diverse needs may have difficulty thriving in such schools due to their prescribed curriculum and the lack of an individualized teaching approach. Many parents struggled to support their kids with new ways of doing math. There was increased pressure to test children and due to political pressures from both sides of the aisle, the movement has fallen out of favor. A final question looms over this topic, and that is: who decides what constitutes essential or common knowledge? In an increasingly divided society, there are no easy answers to this question.

Mastery Learning

Mastery learning includes multiple educational practices based on the principle that if students are given adequate time to study and have appropriate instruction most students can meet the learning standards set for the course. Mastery learning is based on the acknowledgement of the differing rate of time that students take to master material. Theoretically speaking, there could be the possibility that all students will be learning at different paces and the teacher will have to attend to the differences in the pace of instruction of all of their students (Block & Anderson, 1974).

Some advantages of this method is that educators take the time to know their students and therefore, focus their teaching based on the student’s prior knowledge, interests, talents, and preferred ways of learning, making it a culturally responsive approach.

The Affective Domain of Curricula

The affective domain of curricula places emphasis on feeling and valuing in education. This is the aspect of the curriculum that emphasizes emotions and motivation. This domain is rooted in the belief that schools have responsibilities beyond the delivery of instruction. In this domain, the information is presented in a manner that guides students to seeing the value in the things they are learning in the classroom in a way that helps the students see the value in the material that is being covered in the course. It is the goal to make a lasting impression on the students, eliciting an emotional response from the students.

Concerned with the affective side of his students’ education, Paulo Freire developed a liberation pedagogy which has influenced generations of educators, centering the freedom and humanization of students. In his theory, students become active learners as educators pose worldly problems that relate to their lives and push them to analyze how and why those problems exist, leading to a cultural change. He encourages educators to teach through critical pedagogical methods that promote the connection of students to their environment.

The work of Freire inspired bell hooks (amongst many others) who added the concepts of self-care to Freire’s liberatory approach. The Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nat Hanh was another major influence for hooks particularly regarding health and well-being. Self-actualization cannot occur without self-care. Hooks’ holistic concept of “Engaged Pedagogy” centers care and healing in the process of learning. Thich Nhat Hanh was concerned with the whole body, more than just the mind. This wholeness includes mind, body and spirit and emphasizes well-being, a somewhat radical notion in academia.

Deeper Dive: Mindfulness in Schools

The affective domain of curricula emphasizes emotions and motivation. Part of this is taking care of ourselves. Especially recently, educators have to navigate a system that is surrounded by negativity, racism, and hatred. In the following website The Urban Mindfulness Foundation, educators, especially educators of color, can find several resources that will connect them with different people, experiences and feelings.

There is also a REAL TALK video that would teach educators, and other professions, what mindfulness means and the importance of practicing it on a daily basis in classrooms.

Sentipensante

Laura Rendon offers a transformative vision of education that emphasizes the harmonic, complementary relationship between the sentir of feeling, intuition, the inner life and the pensar of thinking, intellectualism and the pursuit of scholarship; between teaching and learning; formal knowledge and wisdom; and between Western and non-Western ways of knowing. In the process she develops a pedagogy that encompasses wholeness, multiculturalism, and contemplative practice, that helps students transcend limiting views about themselves; fosters high expectations, and helps students to become social change agents. Teaching about social justice is central to developing this responsibility in students.

In this video, Laura Rendon describes what it means to be “una persona educada”, a person not only with academic knowledge but a person with wisdom, and responsibility for the world they are living in. She describes contemplative education and how we need to learn to cultivate this wisdom, compassion and humanity.

Video 7.2

CONCLUSION

Curriculum has always been a political and controversial topic because defining what children learn has so much to do with determining what the political and societal future will be. In some states, educators are increasingly limited in what they can teach because education has long been a political battleground. In many cases however, educators have more autonomy than they realize. While it may be true that educators can not teach on certain controversial topics ( such as racism or climate change) they are able to provide assignments and the autonomy for students to do research in those areas. While educators should never tell their students what to think, they can cultivate opportunities for their students to engage in critical thinking about important issues that impact our modern society.

Licenses and Attributions

Foundations of Education: A Collective Reimagining is adapted from the following three texts:

- Foundations of Education by Tasneem Amatullah, Rosemarie Avanzato, Julia Baxter, Thor Gibbins, Lee Graham, Ann Fradkin-Hayslip, Ray Siegrist, Suzanne Swantak-Furman, Nicole Waid. Foundations of Education Copyright © by SUNY Oneonta is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Foundations of American Education: A Critical Lens Copyright © by Melissa Wells and Courtney Clayton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Foundations of Education by Jacqueline M. DiSanto, Hostos Community College under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Modifications by Tanya Mead, Ceci DeValdenebro, Kanoe Bunney and Lisa AbuAssaly George, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted, include a reorganization, videos, images, activities and significant rewriting.

References

Anyon, J. (2019). Anyon: Social Class and the Hidden Curriculum of Work. Udel.edu. https://www1.udel.edu/educ/whitson/897s05/files/hiddencurriculum.htm

Barnett, R. (2009). Knowing and becoming in the higher education curriculum. Studies in higher education, 34(4), 429-440. Block, J. H., & Anderson, L. W. (1974). Mastery learning. Handbook on Teaching Educational Psychology.

Bennett, G., & Conciatori, T. (2023, January 23). DeSantis defends blocking African American studies course in Florida schools. PBS NewsHour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/desantis-defends-blocking-african-american-studies-course-in-florida-schools

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. New York: McKay, 20-24.

Bruner, J. S. (1960). On learning mathematics. The Mathematics Teacher, 53(8), 610-619.

Cineas, F. (2023, February 15). Ron DeSantis’s war on “woke” in Florida schools, explained. Vox. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/23593369/ron-desantis-florida-schools-higher-education-woke

CNN, A. S. (2022, January 20). Florida bill to shield people from feeling “discomfort” over historic actions by their race, nationality or gender approved by Senate committee. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2022/01/19/us/florida-education-critical-race-theory-bill/index.html

Common Core State Standards Initiative. (2019). Common Core State Standards Initiative. Corestandards.org. http://www.corestandards.org/

“Common Core “ by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Confronting Inequity / Reimagining the Null Curriculum. (n.d.). ASCD. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/reimagining-the-null-curriculum

Dewey, J. (1902). The child and the curriculum (No. 5). University of Chicago Press.

Eisner, E. W. (1994). The educational imagination: On the design and evaluation of school programs. Macmillan Coll Division.

Flinders, D. J., Noddings, N., & Thornton, S. J. (1986). The null curriculum: Its theoretical basis and practical implications. Curriculum Inquiry, 16(1), 33-42.

Gibson, R. (n.d.). Anyon: Social class and the hidden curriculum of work. https://www1.udel.edu/educ/whitson/897s05/files/hiddencurriculum.htm

Hammond, Z. L. (2014). Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain. SAGE Publications.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1999). Making cooperative learning work. Theory into practice, 38(2), 67-73.

Miller, M. (2005). Teaching and learning in afective domain. Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. Retrieved March, 6, 2008.

Milner, H. R. (2017). Race, Talk, Opportunity Gaps, and Curriculum Shifts in (Teacher) Education. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 66(1), 73–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/2381336917718804

Mindfulness Training Courses Urban Mindfulness Foundation London. (n.d.). Urban Mindfulness Foundation. Retrieved August 14, 2023, from https://www.urbanmindfulnessfoundation.co.uk/

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy. Scholastics.

Najarro, I. (2022, January 13). Teachers Deliver Less to Students of Color, Study Finds. Is Bias the Reason? Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/teachers-deliver-less-to-students-of-color-study-finds-is-bias-the-reason/2022/01

NYSED. (2017) New York State Next Generation English Language Arts and Mathematics Learning Standards. Retrieved from: http://www.nysed.gov/next-generation-learning-standards

Oregon Department of Education : Academic Content Standards : Standards : State of Oregon. (2010). Oregon.gov; Academic Content Standards : Oregon Department of Education. https://www.oregon.gov/ode/educator-resources/standards/Pages/default.aspx

Ornstein, A. C. (1982). Curriculum contrasts: A historical overview. The Phi Delta Kappan, 63(6), 404-408.

Sentipensante Pedagog – Laura I. Rendón. (n.d.). Retrieved August 14, 2023, from https://www.laurarendon.net/sentipensante-pedagogy/)

UMF Real Talking. (n.d.). Www.youtube.com. Retrieved August 14, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oLp6jKcUlbE&t=29s

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

“Common Core “ by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Unpacking Curriculum: Adopt, Adapt, Apply. (n.d.). Center for the Professional Education of Teachers. https://cpet.tc.columbia.edu/news-press/unpacking-curriculum-adopt-adapt-apply

Wells, M., & Clayton, C. (n.d.). Chapter 6: Curriculum: Planning, Assessment, & Instruction. Viva.pressbooks.pub. Retrieved August 14, 2023, from https://viva.pressbooks.pub/foundationsofamericaneducation/chapter/chapter-6/)

Images

7.1 “Puzzle clipart. “ by Creazilla is in the Public Domain, CC0

7.2 “Planet earth world global – Free Stock Illustrations “ by Creazilla is in the Public Domain, CC0

7.3 “A teacher helps a student in class “ by Flickr is in the Public Domain, CC0

7.4 “Chapter 6: Curriculum: Planning, Assessment, & Instruction”, Viva Open Publishing is in the Public Domain, CC0

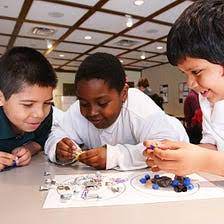

7.5 “Two fourth-grade boys and a fourth-grade girl working together” by Allison Shelley, Flickr is licensed under

7.6 “Tyler Olvera- Medium” by Bakken Museum , Flickr is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

7.7 “We are skipping our lessons to teach you one” by K6ka is in the Public Domain, CC0(2019).

Videos

7.1 – “The consciousness gap in education – an equity imperative “ by Dorinda Carter Andrews, TEDxLansingED is licensed under

7.2 – “How Common Core Broke U.S. Schools” by Youtube is in the Public Domain, CC0

7.3 – “Working Toward a Sentipensante (Sensing/Thinking) Pedagogic Imaginary” by Naropa University, YouTube is licensed under CC BY 4.0