9 Governance and Finance

“Funding education is not a mystery. It is a set of choices. It’s a function of leadership, & we have to have leaders who are willing to have the very real conversations that education costs more for certain children and that the…return on investment lowers our public welfare costs, lowers our incarceration rates and lowers all of the social welfare programs that we have to put in place.”

Stacey Abrams (“personal communication”, February 24, 2019)

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the models of schools present in the United States today, including their funding, enrollment policies, and key characteristics.

- Learn about the inequities behind governing and financing of schools, and how they vary at the federal, state, and local levels

- Describe the current policies surrounding school choice, including charter schools and vouchers.

9.1 Governing Structures in US Schools

In the United States, one must always consider the different levels of governance which impact US schooling: the federal, state and local governing bodies. Because US schooling was initially created and organized at the local level, the federal control is quite different from other countries in the world, in effect creating a more de-centralized system of governance for US schooling. While the original and less significant Department of Education was created in 1867, a more prominent cabinet-level agency was introduced in 1979 under the Carter administration. Historically, local and state educational offices and academic institutions have had significant power to make decisions.

The federal department of education performs duties such as:

- Making policies and regulations for different local educational offices.

- Strengthening educational regulations about civil rights.

- Cooperating with the majority of national federal agencies to support education events.

- Collecting, sorting and analyzing data on American educational institutions including schools, colleges, and universities.

- Improving student achievement for worldwide competitiveness.

- Making sure equal educational opportunities for young people.

Additionally, the United States Department of Education also cooperates with other governmental organizations to improve education quality for children from low-income households.

Key Parts of the United States Department of Education

- United States Secretary of Education: The Secretary is the top executive of the United States Department of Education. The main duties of the Secretary is to provide comments and suggestions on educational policies and projects in the United States.

- Institute of Education Sciences (IES): IES usually carries out research and analysis in order to offer scientific evidence for domestic educational topics. Currently, IES has a number of National Centers for evaluating educational reports and data sets. So far, a large number of American local communities and academic organizations have benefited from the research outcomes of IES.

- Federal Student Aid (FSA): This sub-department in the United States Department of Education mainly supports student financial needs. Every year FSA deals with millions of applications and offers American students different types of grants, loans, and funds from FSA. Students may apply for financial support via some legal federal or private programs in many states and local offices.

- Student Achievement and School Accountability Programs (SASA): This part provides financial support especially for national colleges and universities in the U.S.A. Furthermore, a number of programs, such as the English Language Enhancement and the program for Homeless Children, are involved in better education quality.

- Office of Migrant Education (OME): The Office manages programs to provide academic support to children from migrant families. Typically, migrants in the U.S.A had poor working conditions so couldn’t offer quality education experience to their children. OME aims to provide equal education opportunity to all students regardless of nations and religions.

- Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education (OCTAE): OCTAE, as a sub-division of the United States Department of Education, makes policies for a wide range of educational subjects, such as the postsecondary education, career and technical education, adult education and literacy, rural education and college aid. The Office also carries out statistical research that focuses on high school or community colleges.

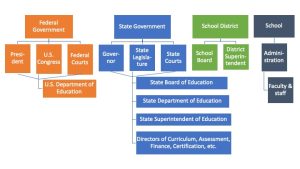

When considering how decisions concerning schools are made, there are various levels of involvement in educational governance at the federal, state and local levels:

The federal government has limited powers, but maintains influence through promoting educational policies and reforms and potentially withholding funding if regulations are not met.

The state government determines standards and policies for the state.

The local school district, sometimes called the local educational agency, is responsible for reporting and working with the state educational agency. At the local level, schools are combined by geographical lines to make up school districts. Finally, schools themselves follow a local governing structure.

Federal

As we stated before, the United States federal government does not have direct authority over schools in each state. It does not tell schools what to teach or how. The department maintains its power

through the distribution of federal education assistance. The head of the U.S. Department of Education is nominated by the president and approved by the Senate (U.S. Department of Education, 2010). It is important to note that federal education acts must include federal funding formulas and methods of distributing federal funds.

The US Department of Education is responsible for:

- promoting policies and reform efforts;

- providing federal assistance appropriated by Congress;

- enforcing civil rights laws pertaining to education; and

- collecting and providing statistics on education (U.S. Department of Education, 2010).

Stop and Investigate – Current

- Who is the current U.S. Secretary of Education?

- What policies have they enacted during their tenure?

- What educational background do they bring with them to the position? https://www.ed.gov/

State

At the state level, there are three major positions that make decisions related to education.

- The governor acts as the chief officer and oversees policy. The governor also has the ability to veto

Image 9.5 and approve legislation.

- The state board of education includes members that act as policy makers and liaisons for educators.

- The chief state school officer, also called the state superintendent, is responsible for administrative oversight of state education agencies. The chief state school officer may be a member of the state board of education, but is directly responsible for making sure policies and state laws are followed.

At the state level, there are many central decisions made for all of the local school districts. First, the state allocates funds to each school district. Later in this chapter, school funding will be discussed, but the state makes up a considerable portion of funds for students. The state also sets standards for assessment and curriculum. It is then up to each locality to decide how the curriculum is implemented. The state is also responsible for licensing public and private schools, charter schools, and teachers and public-school staff (Chen, 2018). In addition, states establish compulsory education laws, which dictate between which ages students must attend school, often from ages five or six through 17 or 18, reflecting the range of the K-12 spectrum.

Local

Most states give responsibility for the operations and accounting to local school systems. These local school systems are defined by school districts. School district boundaries are often determined by geographic lines that may be drawn by county or centers of population. The majority of school districts are then run by school boards. School board members are either appointed by the mayor or city council, or they are elected by the public. The school board then elects a superintendent to oversee the district. The local school district makes decisions on allocation of funding within the district, curriculum, school policies, and employment policies and decisions.

Stop and Investigate – School District

- What school districts are near you?

- How are their boundaries determined?

- How many schools do they contain?

- Check out your local school board and see what decisions they are making.

The most local governance structure occurs in individual schools. Each school has its own leadership structure, usually headed by the principal (Chen, 2018). Other members of the school administration include assistant principals, with the number of assistant principals corresponding to the size of the student body. Administrators of individual schools are responsible for supporting their faculty and staff to fulfill district and state educational policies. Administrators are also liaisons between schools, families, and local communities.

The Hierarchy of the System

You must be wondering now, who is the boss in the school systems? The public school governing system is actually a hierarchy (March, 1978). There are several tiers to this hierarchy beginning with the federal level and ending with the individual teachers. It is a pyramid of administrators doing everything they can to educate today’s students. While some may believe that administration of schools starts with the federal government, the truth is that on the federal level there is very little involvement in education, even in funding (Federal Role, n.d.).

The federal government: The federal government sets some guidelines for education, such as the No Child Left Behind Act, but not specific ones such as curriculum taught. As we stated in our previous chapter, the states have most of the power over their own schools and what they teach (Education Commission of the States [ECS], 1999).

State: The state has the largest financial role in the schools. Most of the federal funding is applied for by the individual school in the form of a grant for a special purpose (Federal Role, n.d.). The states provide teacher salaries and the money required to run each individual school. Each individual school has a parent led group that can help the school gain funds for things like technology (ECS, 1999)

District: Each state is broken up into districts (ECS, 1999). Most administration deals on a small level, either within the district, or in the individual school (March, 1978). The districts each have their own school board made of elected members (Office of the Education Ombudsman, n.d.). Those boards decide how their schools will achieve the standards set by the state. They will also decide anything else they believe the schools should be doing to service their district’s children. Some of these things include overseeing the curriculum and helping to promote better teaching techniques (Education Administrators, n.d.). The board has to have all schools achieving at a level set by the state, so they use their resources to push the schools to achieve the standards they have set (ECS, 1999).

Superintendent: A superintendent is chosen to oversee the schools in the district (ECS, 1999). Much like a politician, this office is often given to those who have worked their way up from the bottom of the hierarchy (March, 1978). They are in charge of making sure the schools are doing what is required by the school board. They make routine visits to schools to check on how they are doing. They work with the principals and teachers to see that children are getting the most out of each school day.

Principal: The district hires principals to oversee each individual school. These principals are there to see that the teachers are doing their job and the children are getting the education they deserve (Office of the Education Ombudsman, n.d.). They are responsible for scheduling, planning the daily activities, and managing the overall activities of the school (Office of the Education Ombudsman, n.d.). Principals make routine visits to classrooms to make sure they are running smoothly and that teachers are making the most of their instructional time. Another difficult duty of the principal is the budget for the school. The principal must decide how to best spend the school’s money (Education Administrators, n.d.).

Assistant Principals: these administrators help the principal in the daily activities of the school. They also handle most of the discipline problems leaving the principal available to focus on other duties (Education Administrators, n.d.).

Teacher: Each school is responsible for the hire of their teachers. The principal can decide who to hire as long as they are qualified by the state (ECS, 1999). Teachers apply for a job through the district and might interview at several schools before being hired by one. Each school is different so principals often look for a teacher who will fit into the school. The teacher has the most direct effect on students. They ultimately decide what happens in the classrooms (ECS, 1999). When the door closes every morning it is up to the teacher to make an effective use of time and get children to those standards set by the state. If children in their classrooms are not performing well, the teacher is held responsible.

9.2 Financing of Schools

As a future teacher you will need to be aware of how schools are organized, governed and financed. Where you work will also determine the amount of money and resources available to you. The federal, state and local government all play a role in the complex financial system of education. Keep in mind that how well a school is funded is often a reflection of the community composition and wealth (number of businesses, homeowners, taxpayers, population size). In this chapter we will learn how schools are governed and financed in public education and begin to explore how these factors impact our ability to help students learn.

School funding follows a similar pattern as school governance. The federal government distributes money to State Education Agencies (SEAs), who then distribute monies to Local Education Agencies (LEAs). The following section will discuss how these funds are distributed and equality issues that arise.

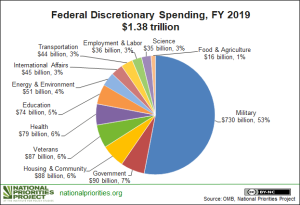

Pause and Ponder – Spending Allocation

How much does our government allocate for education? How does that compare with other spending, notably military spending?

Federal Funding

The Federal government plays an important role in both governance and finance. The President of the United States appoints a Secretary of Education to administer the department and distribute funding to states for educational purposes. In addition, each house of Congress has their own committee on education. Members of these committees provide guidance and expertise as educational policies and budgets are developed. States and local school districts, rather than the Federal Government, make most of the major decisions about the content, assessment, teaching force, structure, and funding of elementary and secondary education. The Federal Government influences educational policy by attaching educational policies to receipt of federal funds (Kober & Usher, 2012).

Now, let’s take a look at how funding was distributed in FY 2022 for the Department of Education (ED) knowing that President Biden proposed a historic $36.5 billion investment in grants for Title I schools to provide support to students who were impacted by the pandemic. This was a $20 billion increase from the 2021 enacted level. (ed.gov). The rationale behind this investment would be to “provide historically under-resourced schools with the funding needed to deliver a high-quality education to all of their students, as well as meaningful incentives for states to examine and address inequities in school funding systems. These additional funds will advance the President’s commitment to ensure teachers at Title I schools are paid competitively, provide equitable access to rigorous coursework, and increase access to high-quality preschool.”

However, the federal government is responsible for providing around nine percent of a school’s budget. The amount of federal funding for schools depends on the annual budget proposed by the president and set by Congress through a budget resolution. SEAs then submit plans to the federal government outlining how they will assess student progress and what their learning outcomes are. The remaining 91% of budgets typically comes from state and local sources, often derived from taxes.

Title I Funding

In 1965, Congress passed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). In this act, Title I, Part A (Title I) provides federal assistance to LEAs and schools with large percentages of students from low-income, under-resourced families. The purpose is to ensure that all children have a fair, equal, and significant opportunity to obtain a high-quality education and reach, at a minimum, proficiency in state academic achievement standards and State academic assessments. The federal government provides funds to SEAs, who then allocate the money to LEAs. The LEAs are then responsible for allocating the funds to each school based on a funding formula. In general, these funds are used for targeted assistance programs, or if more than 40% of the students are eligible for Title I funds, then the funds may be used for school-wide improvement (EdBuild, 2020). The goal of distributing funds in this way is to make schools more equitable; however, these funds only account for nine percent of a school’s funding. The other 91 percent comes from state and local funding.

State and Local Funding

State and local school funding is based on complex funding formulas, with income often sourced from taxes on income, property, or sales. In general, most states use one or a combination of three different types of funding formulas: a student-based formula, a resource-based formula, or a hybrid formula. A student-based formula assumes a set amount that estimates how much it costs to educate one student. Adjustments are then made for students that are low income or receive special services for special education or emerging bilinguals. A resource-based formula uses the cost of resources or programs to fund specific programs. A hybrid funding formula will rely on multiple formulas. In 2020, 38 states used a student-based or hybrid funding formula. Across the nation, each state sets its own education budget, thus creating variance in funding and equitable education across states.

In 2015-16, New York State had the largest per pupil average expenditure in the United States at $24,657 versus Idaho, the lowest state at $7,921 (Digest of Education Statistics, 2018). This demonstrates the variability in funding and resources by state. However, within states variability also exists between communities, largely due to revenues from property taxes. School districts that are wealthier tend to have more money and resources to dedicate to education.

Pause and Ponder – What is happening in your state?

Do you know the average expenditure in your state?

https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/2022-08-26/which-states-invest-the-most-in-their-students

During colonial times, farmers harvested crops on plots of land. In order to educate the children of farmers, colonial regions required farmers to pay a property tax. In this way, each farming community was responsible for contributing to the schooling of the children. Today, the property tax still exists out of the belief that districts and communities must contribute to educating their children. However, only a relatively small percentage of the population farm the land. Citizens from larger districts generally spend more money to educate larger populations of students, and smaller communities contribute less money. Rather than having the federal government maintain control over funding, states control school expenditures.

Today, the property tax is tied to real estate value. Homes which are high in value contribute a higher property tax. More money from wealthy communities are given to schools in these regions. Impoverished communities, or communities with housing that does not have the same value do not have adequate resources and funding to contribute to schools.

On average, individual states spend between $7,000 and $22,000 per year per student. This is the total amount that states spend on each student including the cost of hiring a teacher and running a school. Local states and governments pay for the majority of the educational needs of the students in their state. Federal Government spending accounts for less than 10% of the total cost of educating students. Schools are funded primarily through the property tax system.

The idea behind the property tax system is that families and communities pay for the children who attend school in that region. Even if you do not have a school age child, the concept of providing an education for students in the community involves an aspect of collectivism. Collectivism means that everyone contributes to the needs of all. In the United States, working citizens pay state and federal taxes. One of the taxes is called a property tax.

Video 9.1

It is no secret that teachers spend their own money on school supplies and items for the classroom. On average, teachers spend $459 each year on these classroom items. Sites such as “teachers pay teachers,” assist teachers in creating a place where they can earn money for creating curriculum and materials for other teachers to use. While they try to make up the difference in what they spend in their classrooms, overall, teachers who have the most impact on the everyday lives of students in their classes, have little say in budgets and the amount of money spent on students.

When schools shut down due to mitigating Covid-19 concerns in March of 2020, legislators made decisions which impacted students and teachers. Teachers quickly pivoted, and for the most part created significant changes to their everyday lives with students in the classroom. Although the impact of quarantine reflects an epic event, it reflects how teacher voices aren’t always brought to the table when decisions are made concerning funding in the school setting.

This funding disparity is further widened at the local level. Local funding makes up around 45 percent of a school’s budget. Once a state distributes funds to LEAs, the LEAs are then in charge of distributing funds to each school. In 47 states, funding for education is raised through property taxes (EdBuild, 2020). Thus, schools within wealthy districts will raise more funds than schools in economically disadvantaged areas. The federal funds distributed to low income areas through Title I do not make up for the inequities in funding.

Critical Lens: Inequitable Funding

Funding public schools based on local property taxes can perpetuate issues of inequity when it comes to accessing resources needed for high-quality education. This NPR article (Lombardo, 2019) explains how predominantly White school districts can receive up to $23 billion more than districts that serve predominantly students of color. Watch this video to learn more about how systemic racism impacts school funding.

Video 9.2

Pause and Ponder -Why this should matter to all of us?

Understanding Our Common Interests in Educational Excellence and Equity– by Kimberly J. Robinson

Local School Budget Development Process

As stated above, one of the major roles of the members of the Board of Education (BOE) is to develop a budget in collaboration with administrators. A budget is a plan of financial operation expressing the estimates of proposed expenditures for a fiscal year and the proposed means of financing them. Multiple laws and procedures must be followed during budget development. Educational law emphasizes that the budget should be written in plain language in a manner that taxpayers can understand (NYSED.gov, 2019). When developing a budget, the BOE and administration need to keep several factors in mind and have accurate information about educational objectives, enrollment projection; the community’s receptiveness to tax increases, capacity and limitations of facilities

There are two important terms that BOE members, administrators, taxpayers and teachers alike need to understand are the tax levy and bonds. The difference between levy and bonds is that bonds are for building, or improving current facilities, and levies are for learning. Bonds and levies provide schools with funds that must be used for specific purposes.

The tax levy is the term used for the sum of revenue in property taxes a district must collect, after removing other sources of funding including state aid, to meet the proposed budget. The tax levy is significant because this is the basis for determining the tax rate for each of the cities, towns or villages that make up a school district.

To determine the tax levy, school districts use a state formula that begins with an increase of 2 percent or the level of inflation (whichever is less). The Tax levy limit is the amount a district’s tax levy may increase without requiring a supermajority to approve a proposed budget (60 percent of votes plus one). The result is often a number higher than 2 percent. Under this law, the property taxes levied by affected local governments and school districts generally cannot increase by more than 2 percent, or the rate of inflation, whichever is lower.

In the state of Oregon, the structure of the tax has changed overtime, so we are summarizing how the system has evolved. We start with Measure 5, which introduced tax rate limits, was passed in 1990 and became effective in the 1991-92 tax year. When fully implemented in 1995-96, Measure 5 cut tax rates an average of 51 percent from their 1990-91 levels. Measure 50, passed in 1997, cut taxes, introduced assessed value growth limits, and replaced most tax levies with permanent tax rates. It transformed the system from one primarily based on levies to one primarily based on rates. When implemented in 1997-98, Measure 50 cut effective tax rates an average of 11 percent from their 1996-97 levels.

A school bond election is a bond issue used by a public school district, typically to finance a building project or other capital project. These measures are placed on the ballot by district school boards to be approved or defeated by the voting public. School bond issues on the ballot are different from other areas of the election ballot as state laws require ballot measures to be worded as specific to the point. School bond measures generally do not receive as much attention as candidate elections or state-wide ballot measures, but they are an important way in which citizens can guide school policy. Forty states require voter approval of bond issues as a matter of course, and in seven more, voters can petition to have bond issues placed on the ballot. Of the remaining three states, one of them, Indiana, uses what is known as the remonstrance-petition process.

Education Funding in Oregon

Money to support public education in grades K-12 comes from state income taxes, the lottery fund, local revenues primarily consisting of property taxes, and federal funds. Historically, the largest source of funding had been local property taxes, but this changed dramatically in 1990 when voters passed Measure 5, which lowered the amount of property taxes dedicated to schools. By the 1995-1996 school year, local property taxes for education were limited to $5 per every $1,000 of a property’s assessed real market value. In 1997, voters passed Measure 50, which further limited local property taxes for schools by placing restrictions on assessed valuation of property and property tax rates. The effect of these measures was to shift the bulk of public school funding from local property taxes to Oregon’s General Fund, which comes from state income taxes.

Oregon uses a formula to provide financial equity among school districts. Each school district receives (in combined state and local funds) an allocation per student, plus an additional amount for each student enrolled in more costly programs such as Special Education or English Language Learners. The 2021-2023 legislatively adopted General Fund and Lottery Funds budget for the Education program area is $12.624 billion. This was an increase of $1.1 billion (or 9.9%) from the 2019–2021 legislatively approved budget.

Access and Equity in Education funding

As we think about funding for schools, we turn our thoughts to equity and equality in education. Included below is a short video describing equity and equality in more general terms. As a teacher you will have to make decisions on how best to meet the learning needs of your students.

Local budgets will determine the types of materials and resources both teachers and students will have access to. For example, access to technology, opportunities for professional development, updated textbooks and materials, access to field trips, and availability of extracurricular opportunities are a few ways that budgets impact schools and students. In a school with fewer resources how can you make your materials equitable (fair) to the resources wealthier districts have? As a teacher the question of equity of resources is one you will need to get involved in. Advocating for equitable curricular and program resources for your students is an appropriate role for teachers.

Video 9.3

There are multiple ways in which the quality of education is challenged by issues pertaining to equity and access. For example, since the property tax is where much of the school funding is received, the value of homes in a certain district affects the amount that is spent on each student. In the past, families have challenged the allocation of funding per student. One of the landmark cases involves a man named Demetrio Rodriguez. Rodriguez and his family lived in Edgewood, a neighborhood located in San Antonio in the 1960s. He sent his children to a school where the top two floors were condemned. Less than half of the teachers in the school were licensed. The textbooks were falling apart and the school lacked air conditioning. The majority of children who attended this school were Mexican-American. The district allocated $37 per student. In close proximity, Rodriguez noted Alamo Heights, a wealthier district which spent $413 on each student, and the students who attended schools in Alamo Heights were predominantly White. Rodriguez and other families filed a class-action suit and argued that unequal access was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court case, San Antonio ISD v. Rodriguez (1973) was a landmark case because it was the first to challenge the equity of school funding. The court did not rule in favor of Rodriguez; however, it triggered a series of ongoing struggles concerning the quality of education for all students in the U.S.

Video 9.4

Following the Rodriguez v. San Antonio many cases involving school funding ensued. Currently, Teachers College, Columbia University hosts a project entitled, SchoolFunding.info in order to seek equity in school funding. This project provides a national lens and view of the nationwide effort to uncover inequities in expenditures for students. It surveys the current area involving state spending and continues to show how the court system continues to struggle to define an adequate education. While the definition of “Adequate,” continues to change, it was determined by the Supreme Court that an adequate education is a set of minimum state academic standards, or what students should be able to know and do at each grade level, and this definition is still the subject of debate in many states. In fact, after the Rodriguez ruling, it was decided that states, rather than the federal government, should design a plan to ensure equal access to schools that received equal funding.

The cases which followed Rodriguez v. San Antonio involved challenges to equity and access in schooling. In Milliken v. Bradley (1974) in Detroit, Michigan, the Supreme Court ruled that the school systems were not responsible for desegregation across district lines unless it could be shown that they had each deliberately engaged in a policy of segregation.

Models of Schools

Although this chapter is primarily focused on the governance and finance of public schools, we will briefly describe other options that may be available to students.

As we have been learning, the majority of schools in the United States fall into one of two categories: public or private. A public school is defined as any school that is maintained through public funds to educate children living in that community or district for free. The structure and governance of a public school varies by model, but shares the characteristics of being free and open to all applicants within a defined boundary. A private school is defined as a school that is privately funded and maintained by a private group or organization, not the government, usually by charging tuition. Private schools may follow a philosophy or viewpoint different from public schools; for example, many private schools are governed by religious institutions.

There are a variety of public school models, including traditional, charter, magnet, Montessori, virtual, alternative, Community-based and language immersion schools. Private school models include traditional, religious, parochial, Montessori, Waldorf, virtual, boarding, and international schools.

One type of school not listed above is homeschool. Homeschooling is a type of schooling that would not fall into either the public or private category. Homeschooling is defined as a child not enrolling in a public or private school, but receiving an education at home. Each state has its own rules and regulations that families must follow and report on if homeschooling. For example, the Oregon Department of Education requires that families inform the school division of their decision to homeschool their child, update the school district with the student’s annual academic progress, and provide evidence that the homeschool instructor (such as a parent) meets specific qualifications to fill the role.

Pause and Ponder – School Models

- Which type(s) of school model(s) did you experience as a student?

- What were some benefits and drawbacks you experienced in that model of schooling?

Critical Lens – Redlining

Video 9.5

Although the Supreme Court made segregated schools illegal in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, you will see many schools today that continue to have student populations that are separated by race or socioeconomic status. Brown v. Board attempted to end what is known as de jure segregation, or segregation that is mandated by the law. However, segregation continued to persist even though the law did not mandate it due to a practice called redlining, in which housing was allowed or denied in certain areas based on people’s race or socioeconomic status. Redlining has resulted in ongoing de facto segregation, which means that while overt segregation was outlawed, it still continues in other ways due to this history of redlining. In this map from EdBuild[1], you can see the relationships between racial/socioeconomic segregation and access to educational resources. In contrast, de facto segregation is the result of separation according to race even though the law does not require it. An example of de facto segregation can be seen in some schools where in fact, African Americans and/or Latinx make up the majority of the population of the school. Redlining, or housing discrimination leads to de facto school segregation.

School Choice

Some public school models, including charter, magnet, and language immersion, may have more students desiring to apply than there is space. In these schools, applications or lotteries may be used. An application system allows the schools to choose students based on characteristics, such as grades, demographic diversity, or geographic area. Often these schools are looking for high-achieving students or have a mission of diversifying the school. A lottery system gives each student that has applied an equal chance of attending and is decided by randomly selecting names from the pool of students.

With so many school models available in the U.S., how do families choose which type of school their child should attend? School choice is a complex issue for families to navigate. What may be best for one student is not always best for another. The choices for students also vary by geographic and socioeconomic boundaries. Many families make school decisions based on the following factors:

- transportation and distance to chosen school;

- cost or tuition of school;

- curriculum and programs available;

- religious affiliation; and

- fit for the individual student.

Families in some areas of the U.S. also have greater access to the different models of schools presented at the beginning of this chapter than others. Small rural towns may only have one school within the immediate area. However, federal reform policies, such as No Child Left Behind (NCLB), have increased the number of charter schools and use of vouchers.

Activity – Stop and Investigate

Go to edchoice.org to explore what resources are available to support families with school choice options.

In 2001, when NCLB was signed into law, federal and state funds required schools to make an Annual Yearly Progress (AYP) report, based on assessment data. Schools that did not meet AYP for two consecutive years were often required to earmark money for student tutoring or allow students to transfer. When a student transfers, the school’s funding formula decreases by one student, resulting in a loss of funds for the school. If a school continues to not meet AYP, then the school may be closed. When a school is closed, it often becomes a charter school (Brookhart, 2013).

As shown earlier in Table 4.1, charter schools are often publicly funded, but they do not have the same requirements as a traditional public school. When a student transfers out of a traditional school to a charter school, the funds follow the student. Charter schools are autonomous from public schools and to operate must meet the educational goals set forth in their charter. Charter school admittance is also application based, usually being first come, first served or by lottery. In 2010, charter schools comprised six percent of public school students, but now the number is closer to 30 percent in some localities (Prothero, 2018).

Why does it matter if public schools become charter schools? In many regions, like Minneapolis-St. Paul, California, and Texas, charter schools are more segregated than the public schools within those same boundaries, which were already highly segregated (Institute on Race and Poverty, 2008). Because charter schools rely on applications for admission, parent participation in the admission process also separates students by socioeconomics (Frankenberg et al., 2011).

Online Learning

When online learning began for K-12 students, there were just 50,000 students who enrolled in this alternative setting. (Patrick, 2011). Online learning has been studied extensively due to the rise in digital learning platforms in 2020 when the Covid era served as a catalyst for school closings.

Online learning began from earlier models called distance learning or correspondence courses. Students would receive instruction through the mail as far back as the 1920s. Later in the mid 1980s these remote schools began to allow students to submit assignments through electronic mail. Evidence indicates that by the mid 1990s, several states were engaged in some type of virtual instruction.

To define these involving models of instruction, several terms must be addressed. Researchers Watson and Murin (2012, p. 4) note that blended learning involves somewhat of a hybrid learning experience. Individuals participate in a formal course which integrates a classroom environment with an online course where they exercise some control over “time, place, path and/or pace,” within the class. In contrast, online learning does not provide a hybrid experience and all teaching learning takes place over the internet and can involve a singular course or an entire school. A term that includes all of these models is referred to as digital learning (Watson & Murin, 2012, p. 4).

Before the 2020 pandemic, students who opted to learn in this way needed access to the internet. A study conducted by Tamara Tate and Mark Warschauer (2022) found that “Underrepresented and low-income high school students have been most likely to use online courses for credit recovery, remediating failing grades” (Tate & Warschauer, 2022). It is difficult to research the impact of the pandemic since districts often blended learning and some students were able to return to school for part of the time earlier than others. However, another study indicated that students who moved to online learning between March 2020 and April 2021 lost ½ to 1 year’s worth of learning in language arts. Vulnerable populations including students who come from low-income homes or ethnic minorities were at an increased disadvantage. When looking specifically at measures which include “race, income, homelessness, disability, and English learner status, [these individuals] experienced declines that were one and one-half to two times higher than their peers” (Tate & Warschauer, 2022).

Vouchers

One reason that school choice has become so politicized is the use of school vouchers. School vouchers are defined as “a government-supplied coupon that is used to offset tuition at an eligible private school” (Epple et al., 2017, p. 441). In the 1960s, some of the first school vouchers were awarded to promote desegregation. School voucher policies and programs today vary across localities and are present in over thirty states. Students who receive vouchers enroll in a private school, which receives those funds. The voucher may cover tuition in full, or offset it significantly. This video explains some of the pros and cons of vouchers.

Vouchers are funded by one of the following: tax revenues, tax credits, or by private organizations (Epple et al., 2017). The majority of states that use tax revenues to fund their vouchers provide vouchers to under-resourced students. For example, Milwaukee, Cleveland, New Orleans, and Washington, DC provide vouchers to students whose family income is just above the poverty line. Some areas, such as in Ohio and Indiana, provide vouchers using tax revenues to all students in failing school districts.

Some states (including Florida, Iowa, Georgia, Indiana, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island) utilize tax credits to fund vouchers. Businesses in these states that fund vouchers are provided a tax credit. For example, Florida businesses can receive 100 percent corporate tax income credit up to $559.1 million dollars (EdChoice, 2019). In addition to tax revenues and tax credits, many states also have privately funded voucher programs. One notable voucher program is the Children’s Scholarship Fund, which was founded with contributions from the Walton Family Foundation (Epple et al., 2017).

Consequences of Vouchers

When a student uses a voucher to attend a private school, this changes the funding formulas for a local school. This student is no longer included in the funding formula for the LEA or SEA. This means that the local and state budget is lowered because one less student is being counted in that funding formula. School vouchers are provided and promoted to give under-resourced students school choice, but not all students have equal opportunities.

Public schools allow and are required by law to provide services for all students. While policies prohibit private schools from discriminating against students based on race, many religious private schools may consider religious affiliation, sexual orientation and disability in their admission decisions. Certain states want to create laws which limit what is taught in public schools, whereas other states let districts have autonomy in the decision-making process within classrooms and schools. For example, there are currently 9 states who banned Critical Race Theory (CRT) in their schools. The issue is that some legislators do not take the time to understand the concept and the impact that banning CRT has in our communities of color. CRT actually celebrates and uplifts the strength of communities of color while standing up for racial justice.

On the other hand, private schools are not exempt from discrimination laws, but the application process allows them to choose which students to admit. For example, a private school receiving government funds must provide students with disabilities with accommodations, unless these accommodations change the philosophy of the academic program, or create “significant difficulty or expense.” A large portion of private schools do not hire teachers trained to provide accommodations; thus, many claim they do not have the resources to serve students with disabilities. Vouchers are not beneficial for students with disabilities that cannot attend private schools, but vouchers also hinder these students further by diverting funds from the public schools, who do provide these services, when other students use vouchers.

Critical Lens – Consider other ways to conceptualize “wealth”

Dr. Yosso’s Cultural Wealth Model

https://scalar.usc.edu/works/first-generation-college-student-/community-cultural-wealth.10

Conclusion

While many individuals and groups call for school reform in order to provide equity to all students, the process is complex. As you have seen in this chapter, federal oversight of schools is somewhat limited, allowing school governance to be different within each district and state. What may seem beneficial for students in one school or community may not be beneficial for students in another school or community; therefore, the federal government leaves many decisions about education to the discretion of state and local agencies. Many school, district, and state policies are also tied to federal, state, and local funding, which all use a variety of funding formulas. In order to create change, it is important that an individual understands how policy and funding decisions are developed and implemented.

School choice and the varied school models within the U.S. also makes school reform highly political. While families are given the right to choose their own child’s education, many families’ choices are constrained by geographic and economic resources. Educational professionals, policymakers and stakeholders have a responsibility to serve all students, and that means practicing equity in decision-making and teaching, ranging from curriculum construction, instructional practice, and policy advocacy that provides each student with what they need to succeed and thrive. The landscape of schools in the U.S. is constantly changing, but one principle will remain as the foundation of schools in this country: everyone deserves access to education.

Licenses and Attributions

Foundations of Education: A Collective Reimagining is adapted from the following three texts:

- Foundations of Education by Tasneem Amatullah, Rosemarie Avanzato, Julia Baxter, Thor Gibbins, Lee Graham, Ann Fradkin-Hayslip, Ray Siegrist, Suzanne Swantak-Furman, Nicole Waid. Foundations of Education Copyright © by SUNY Oneonta is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Foundations of American Education: A Critical Lens Copyright © by Melissa Wells and Courtney Clayton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Foundations of Education by Jacqueline M. DiSanto, Hostos Community College under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Modifications by Tanya Mead, Ceci DeValdenebro, Kanoe Bunney and Lisa AbuAssaly George, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted, include a reorganization, videos, images, activities and significant rewriting.

References

About / about title I. (n.d.-c). https://www.eseanetwork.org/about/titlei

Beardsley, Kathy. Fiddemon, Rose. Los, Mike. Markell, Deb. Morrison, Sarah. O’Connor, Jay. Scarcella, Alyssa. (2018, April). Budget Development School District Guidelines. https://www.questar.org/. https://www.questar.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Budget-Development-Guidebook.pdf

Budgeting Handbook:Educational Management:NYSED. (n.d.). https://www.p12.nysed.gov/mgtserv/budgeting/handbook/process.html

Burris, C., & Bryant, J. (2019, April 17). Asleep at the Wheel:. Retrieved from http://networkforpubliceducation.org/asleepatthewheel/

DCimarusti. (2019, December 3). Asleep at the Wheel: – Network For Public Education. Network for Public Education. https://networkforpubliceducation.org/asleepatthewheel/

Digest of Education Statistics, 2018. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_236.70.asp

Douglas, A. (2022, April 22). Teachers have little say when school districts make decisions. Here’s how we change that. EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2022-02-10-teachers-have-little-say-when-school-districts-make-decisions-here-s-how-we-change-that

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ed.gov/essa?src=policy

Foundation, R. W. (2018, August 06). Equity vs. Equality. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MlXZyNtaoDM

Hanson, M. (2023, February 27). Education Data Initiative: College Costs & Student Loan research. Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/

Jacqueline M. DiSanto, Hostos Community College. (n.d.). Governance. Pressbooks. https://library.achievingthedream.org/hostoseducation/chapter/foundations-of-education-and-instructional-assessmentschool-organizationgovernance/

Kober, N., & Usher, A. (2012). A public education primer: Basic (and sometimes surprising) facts about the U.S. education system. Washington, DC: Center on Education Policy.

Manzanetti, Z. (2021). Education Spending Per Student By State. Governing. https://www.governing.com/finance/education-spending-per-student-by-state.html

Oregon Department of Revenue. (2009, June). A Brief History of Oregon Property Taxation. https://www.oregon.gov/. https://www.oregon.gov/DOR/programs/gov-research/Documents/303-405-1.pdf

Overview of litigation history. (2023, August 16). SchoolFunding.Info. http://www.schoolfunding.info/litigation-map/

Patrick, S. (2011). New learning models: The evolution of online learning into innovative K–12 blended programs. Educational Technology, 19-26.

President’s FY 2018 Budget Request for the U.S. Department of Education. (2018, May 23). Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/budget/budget18/index.html

Reaching Higher NH. (2023, August 9). Home – ReachingHigherNH. ReachingHigherNH. https://reachinghighernh.org/

Research Guides: A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States: 1973: San Antonio ISD v. Rodriguez. (n.d.). https://guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/sanantonio-isd-v-rodriguez

Sadker, D. (2021). Teachers, Schools and Society, New York: McGraw Hill.

School bond election – Ballotpedia. (n.d.). Ballotpedia. https://ballotpedia.org/School_bond_election

State of Oregon: Blue Book – Public Education. (n.d.). https://sos.oregon.gov/blue-book/Pages/education-public.aspx

Tate, T., & Warschauer, M. (2022). Equity in online learning. Educational Psychologist, 57(3), 192–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2022.2062597

The Constitution of the State of New York. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.dos.ny.gov/info/constitution/article_11_education.html

Title I, Part A – Improving Basic Programs Operated by Local Education Agencies. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.nysed.gov/budget-coordination/title-i-part-improving-basic-programs-operated-local-education-agencies

U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/statement-secretary-education-miguel-cardona-presidents-fiscal-year-2022-budget)

Walker, T. (n.d.). Teacher spending on school supplies: A State-by-State Breakdown | NEA. https://www.nea.org/advocating-for-change/new-from-nea/teacher-spending-school-supplies-state-state-breakdown

Watson, J., & Murin, A. (n.d.). A History of K-12 Online and Blended Instruction in the United States. Evergreen Education Group. https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/2811036.2811038

Wells, M. (n.d.-b). Chapter 4: Schools in the United States. Pressbooks. https://viva.pressbooks.pub/foundationsofamericaneducation/chapter/chapter-4/

IMAGES

9.1 “Public Domain Money Images “ by Raw Pixel is in the Public Domain, CC0

9.2 “American Indian Sovereignty Project Files Brief in Denezpi v. United States” by MaxPixel’s contributors , Yale University is licensed under CC BY 4.0

9.3 “School Governance and Finance” by MTSU Pressbooks is licensed under CC BY 4.0

9.4 United States Department of Education” by Wikipedia is in the Public Domain, CC0

9.5 “Oregon Department of Education” by State of Oregon is licensed under CC BY 4.0

9.6 “Racist Controversies Prompt Changes At Two Regional School Boards – OPB” by Molly Solomon, Oregon Public Radio is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

9.7 “The Militarized Budget 2020” by national priorities is in the Public Domain, CC0

9.8 “Property Tax -Real Estate 6” by is licensed under CC BY 4.0

9.9 “File:Okaloosa County School Board Prayer Chaos” by Susan Gerbic , Wikipedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 4.0

9.10 “Update on health conversations in the budget – State of Reform | State of Reform” by is licensed under CC BY 4.0

9.11 “Putting it Together: Technology and Online Learning” by Brian J. Matis is in the Public Domain, CC0

9.12 “Smiling Boys and Girls in School Uniforms” by Ron Lach, Pexels is in the Public Domain, CC0

9.13 “2021/2 GEM Report Background Papers | Global Education Monitoring Report” by is in the Public Domain, CC0

VIDEOS

9.1 “The Dilemma of public school funding | Lizeth Ramirez “, Youtube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

9.2 “Systemic Racism Explained” by act.tv, Youtube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

9.3 “Equity Vs Equality” by Beyer High YouTube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

9.4 “Why Diverse Schools Matter” by The Century Foundation, Youtube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

9.5 “Housing Segregation and Redlining in America: A Short History” by National Public Radio, Youtube is licensed under CC BY 4.0