4.2 Diversity Is More than Just Culture

Culture is one of those words that is difficult to explain and differs according to its use and context, even within academic disciplines. Culture, according to one source, is defined as “the collective programming of the human mind that distinguishes the members of one human group from those of another. Culture in this sense is a system of collectively held values” (Hofstede, 1991). Culture also includes “a learned set of shared interpretations about beliefs, values, norms and social practices which affect behaviors of a relatively large group of people” (Lustig and Koester, 1999). For the purposes of this text, culture refers to the set of beliefs, customs, and rituals shared by a group of individuals. This may refer to a group of people who identify with a certain place (such as indigenous groups) or with a particular religion (such as people who identify as Jewish). As an intern, you may meet people from a variety of cultures—some you may share yourself, some you may be familiar with, and some that are new. This can create challenges for you on a daily basis.

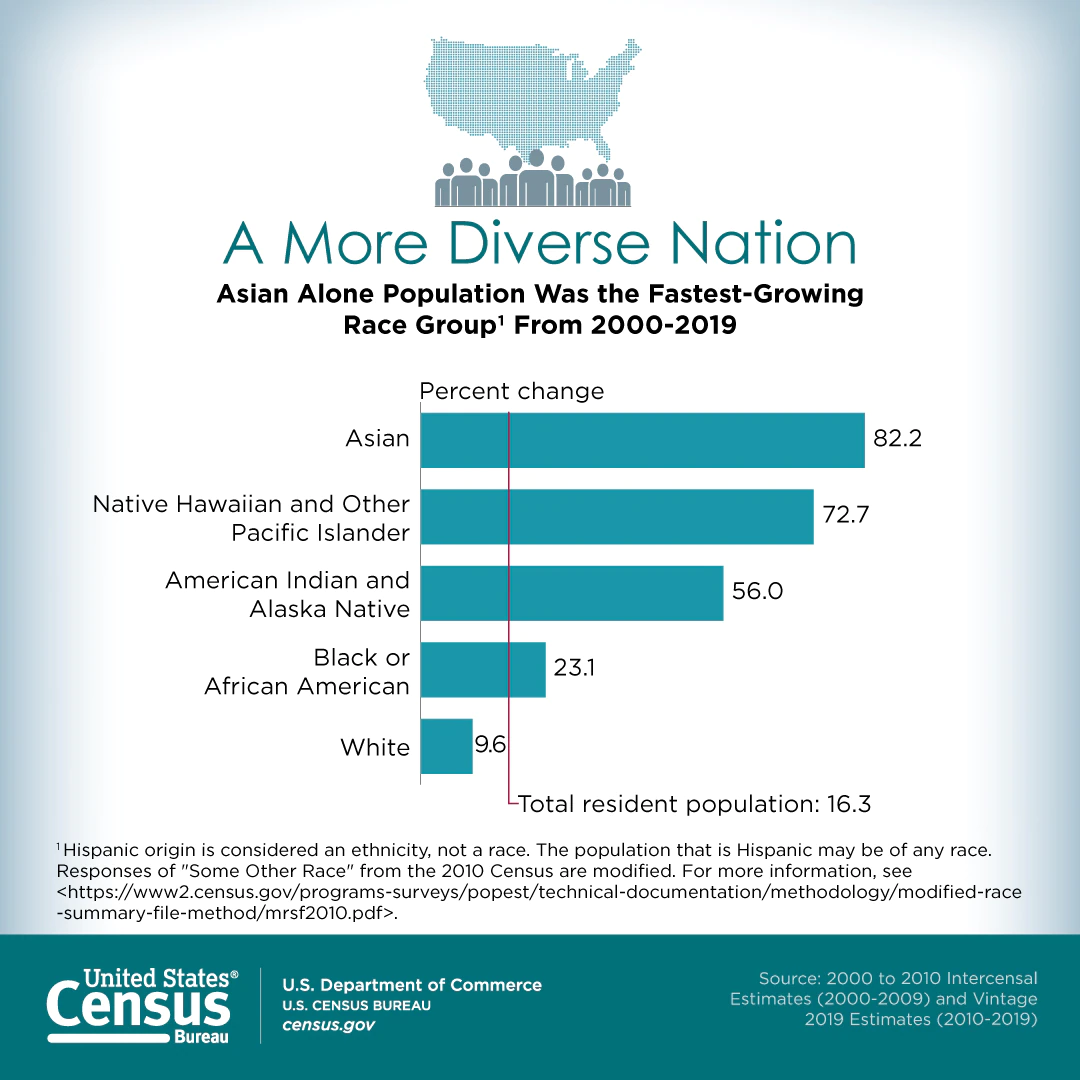

Understanding what culture means is not easy when a society is composed of several racial and ethnic groups with a long history of subjugation and marginalization. Since the 1790 census, the United States’ racial and ethnic diversity has grown exponentially. The latest U.S. Census (2020) shows the following racial and ethnic makeup:

- 57.8% White

- 16.3% Hispanic or Latino (of any race)

- 12.6% Black or African American

- 6.2% other races

- 4.8% Asian

- 2.9% two or more races

- 0.9% American Indian and Alaska Native

- 0.2% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander

As you can see from this data, people of color make up almost half of the population, yet this population is overrepresented in all social deficits, such as poverty, incarceration, homicide, and low medical care measures. The graphic in figure 4.1 shows how US demographics have changed over the past 20 years.

Cultural identity in the United States is inextricably linked to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Throughout the nation’s history, cultural identity has been a divisive force that prevented access to resources, rights, and benefits to those who did not conform with the predominant racial majority. This historical dynamic has shaped the identity of the nation.

Using an Equity Lens

As an intern, you will be encouraged to use an equity lens when working with clients. An equity lens involves creating the conditions that will enable underserved and marginalized populations to advance toward a level that is economically and socially equitable with that enjoyed by the dominant classes (Equity Lens, 2019).

Recent changes in the United States’ diverse population and its representation in public and private institutions show more people of color holding positions of power than in previous generations. But that does not mean that people of color in the United States have reached parity—that is, the same level of socio-economic status that the dominant classes enjoy. Disparities continue across the nation. These disparities adversely affect marginalized people, who have systematically encountered greater socioeconomic barriers to employment, housing, and healthcare simply because of their race, ethnicity, religion, gender, physical disability, sexual orientation, or other characteristics historically associated with discriminatory or exclusionary practices.

The United States has become more segregated, both economically and racially, in recent decades. In 1970, 15% of families in the country lived in neighborhoods where residents were either quite rich or quite poor, yet 40 years later, that figure had more than doubled, with a third of households living in economically segregated communities. Economic inequality in the United States has returned to levels not seen for more than 90 years in part because of continued “White flight,” or purposeful relocation of White Americans from racially diverse urban areas to predominantly white suburbs. US schools are becoming more segregated at the same time that the country’s population is becoming more diverse (Owens, 2019).

The concept of the equity lens has been applied in the educational field, but it also has other applications for the inclusion of oppressed populations—in other words, the least served and most underrepresented segments of society. Using an equity lens, you can focus on understanding what equity work is required to address individual and group needs and how you can best serve the people most impacted by inequity and historical neglect.

Looking at the Micro, Meso, and Macro Levels

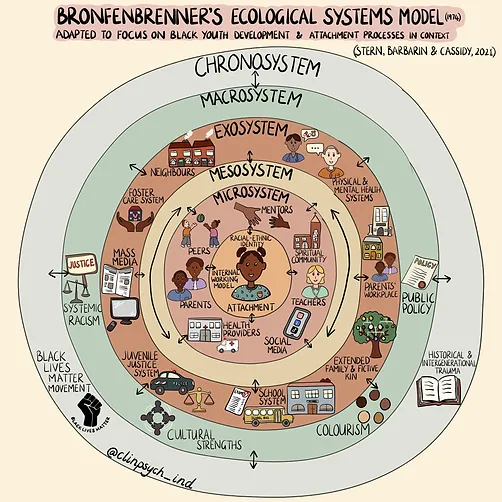

The previous section showed how equity is addressed by removing barriers to opportunities. The following section looks at individuals in their own setting. We humans are social by nature and need considerable interaction with our caregivers and our social environment to fully develop physically and mentally. To study the development of an individual based on the genetic inheritance (nature) and the external or environmental factors contributing to or hindering the individual’s growth and development potential (nurture), the bioecological model of human development has been used. This model was first proposed by Russian-American developmental psychologist Uri Bronfrenbrenner as an extension of his theoretical model of human development, called ecological systems theory. You can use this model to analyze the issues faced by your clients: How are these problems created or sustained at the different levels, and how can you create solutions at the different levels?

Bronfrenbrenner’s model emphasizes the complexity of the environments and systems that each individual interacts with. Each level is represented by a concentric circle. In helping professions, professionals support individuals to identify what is working well and what is negatively impacting them within multiple systems and environments (figure 4.2).

The bioecological model consists of the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem. For example, when analyzing human poverty, sociologists look at individuals in their social setting of family and friends (the microsystem). The poverty that the family experiences is impacted by whether or not they have access to the services and resources offered by the community (the exo-system). When looking at a population from an exo-system research perspective, social scientists study community groups, including teams, units, and organizations, working on behalf of a population. The ability of the community to support its members is also impacted by funding and statutes at the state and federal level (the macro level). Macro-level research delves deeper into the broader, more influential spheres of society, such as the political-administrative environment, which may include national government institutions or systems, regulating bodies, and even cultures. In essence, the individual belongs in the microsystem; the organizations, city services, and support are in the exosystem; and the largest system, which makes all the inner systems function properly, is the macrosystem—the largest and most powerful institutions, cultural and societal beliefs, gender norms, and religious influences.

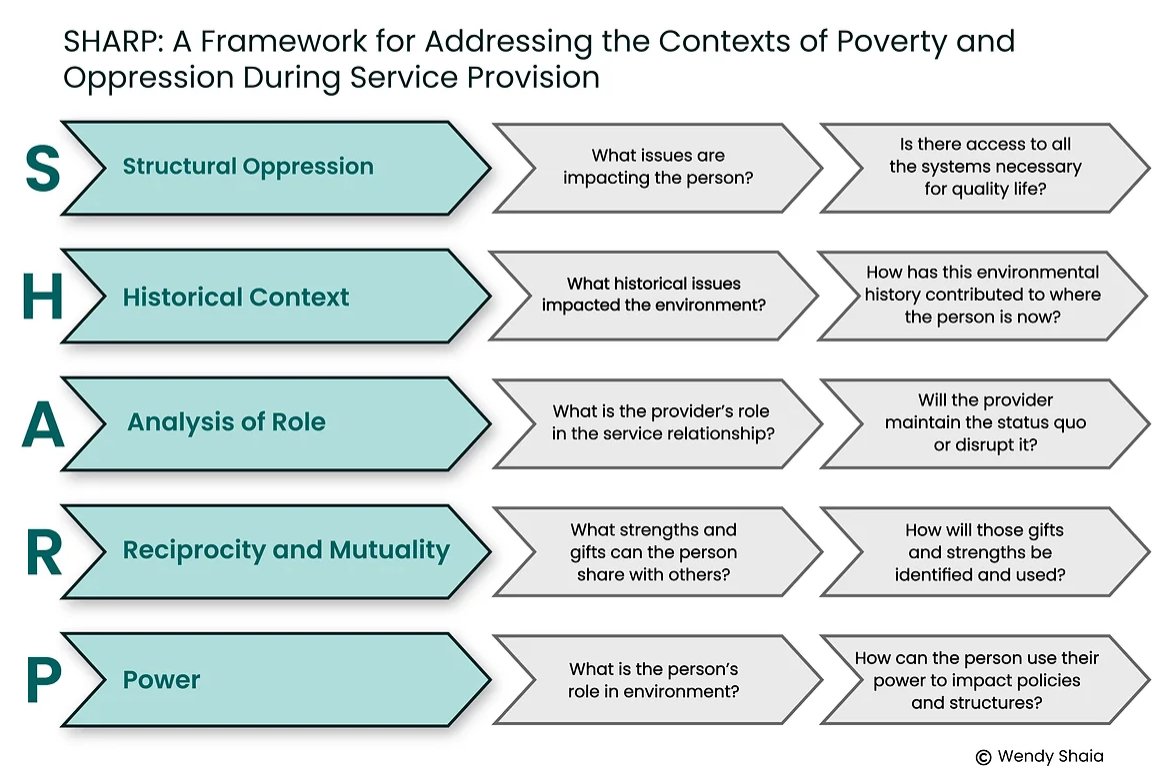

Using the SHARP Framework

The SHARP framework is a structured analysis used by human services and social workers to examine and identify the sources of oppression and societal structures that continue to negatively affect the lives and the quality of life of their clients (Shaia, n.d.). This model can help you examine what sources may be contributing to the issues addressed by your agency. SHARP stands for the following functions:

- Structural oppression

- Historical context

- Analysis of role

- Reciprocity and mutuality

- Power

The graphic in figure 4.3 shows the framework’s application to poverty and oppression and the resulting consequences.

Understanding Intersectionality

In 1991, legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw first described the concept of intersectionality, the idea that people experience multiple parts of their identity simultaneously and that these parts of themselves shape and are shaped by one another. In other words, the frameworks of race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity affect how an individual is seen by others and also influence how those identities are interpreted. For example, a person is never perceived as just a woman. How that person is racialized impacts how the person is perceived as a woman. So, notions of blackness, brownness, and whiteness always influence gendered experience, and there is no experience of gender that is outside of an experience of race. In addition to race, gendered experience is also shaped by age, sexuality, class, and ability; likewise, the experience of race is impacted by gender, age, class, sexuality, and ability.

Intersectional Way of Thinking

Understanding intersectionality requires a particular way of thinking. It is different from how many people imagine identities operate. An intersectional analysis of identity is distinct from single-determinant identity models and additive models of identity. A single-determinant model of identity presumes that one aspect of identity—say, gender—dictates one’s access to or disenfranchisement from power. An example is the concept of “global sisterhood,” or the idea that all women across the globe share some basic common political interests, concerns, and needs (Morgan, 1996). If women in different locations did share common interests, it would make sense for them to unite on the basis of gender to fight for social changes on a global scale. Unfortunately, if the analysis of social problems stops at gender, what is missed is an attention to how various cultural contexts shaped by race, religion, and access to resources may actually place some women’s needs at cross-purposes to other women’s needs. Therefore, the single-determinant model obscures the fact that women in different social and geographic locations face different problems. Although many White, middle-class women activists of the mid-20th-century United States fought for freedom to work and legal parity with men, this was not the major problem for women of color or working-class White women, who were already actively participating in the US labor market as domestic workers, factory workers, and slave laborers since early US colonial settlement. Campaigns for women’s equal legal rights and access to the labor market at the international level are shaped by the experiences and concerns of White American women, while women of the Global South, in particular, may have more pressing concerns: access to clean water, access to adequate health care, and safety from the physical and psychological harms of living in tyrannical, war-torn, or economically impoverished nations. Using a single-determinant model also undervalues the impact of other factors such as gender identity, sexual orientation, and disability.

In contrast to the single-determinant identity model, the additive model of identity simply adds together privileged and disadvantaged identities for a slightly more complex picture. For instance, a Black man may experience some advantages based on his gender, but he has limited access to power based on his race. An Asian man may experience some privileges based on his gender, but he faces oppression due to using a wheelchair or experiencing an unseen disability.

Intersectional Feminism

The additive model does not take into account that our shared cultural ideas of gender are racialized, that our ideas of race are gendered, and that these ideas structure access to resources and power—material, political, interpersonal. Sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (2005) has developed a strong intersectional framework through her discussion of race, gender, and sexuality in her historical analysis of representations of Black sexuality in the United States. Hill Collins shows how contemporary White American culture exoticizes Black men and women, and she points to a history of enslavement and treatment as chattel as the origin and motivator for the use of these images. In order to justify slavery, White people thought of and treated Black people as less than human. Plantation owners often forced sexual reproduction among enslaved people for their own financial benefit, but they reframed this coercion and rape as evidence of the “natural” and uncontrollable sexuality of people from the African continent. This reframing was not completely the same for Black men and women: Black men were constructed as hypersexual “bucks” with little interest in continued relationships, whereas Black women were framed as hypersexual “Jezebels” that became the “matriarchs” of their families. Again, it is important to note how the context, in which enslaved families were often forcefully dismantled, is often left unacknowledged and how contemporary racialized constructions are assumed and framed as individual choices or traits. It is shockingly easy to see how these images are still present in contemporary media, culture, and politics—for instance, in discussions of American welfare programs. Intersectional analysis reveals how race, gender, and sexuality intersect. We cannot simply pull these identities apart because they are interconnected and mutually reinforcing.

Although the framework of intersectionality has contributed important insights to feminist analyses, there are problems. Intersectionality refers to the mutually co-constitutive nature of multiple aspects of identity, yet in practice this term is typically used to signify the inclusion of “women of color,” which effectively renders women of color (in particular, Black women) as “other” and again centers White women (Puar 2012). In addition, the framework of intersectionality was created in the context of the United States; therefore, use of the framework reproduces the United States as the dominant site of feminist inquiry and the Euro-American bias of women’s studies (Puar 2012). Another failing of intersectionality is its premise of fixed categories of identity, where descriptors like race, gender, class, and sexuality are assumed to be stable. A truly intersectional approach would include the more nuanced issues faced by people who identify as nonbinary, trans, multiracial, or other more fluid categories.

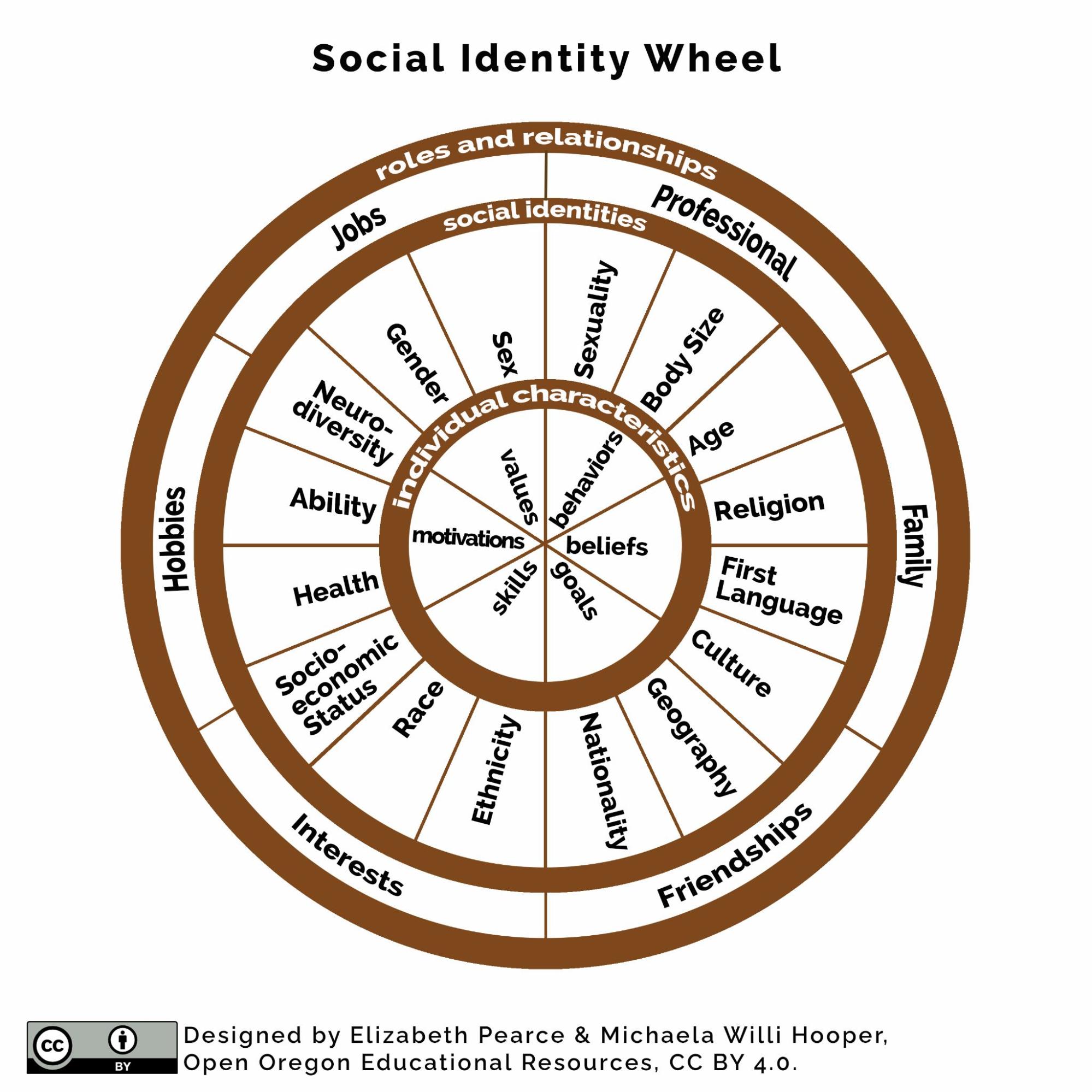

An intersectional perspective examines how identities are related to each other in our own experiences and how the social structures of race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability intersect for everyone. As opposed to single-determinant and additive models of identity, an intersectional approach develops a more sophisticated understanding of the world and how individuals in differently situated social groups experience differential access to both material and symbolic resources. Figure 4.4 visualizes the multiple intersections of identity in a wheel, with social identities expressed through roles and relationships in society. Similarly, individuals internalize social roles and make them real through their actions and beliefs.

Viewing identity through a framework like figure 4.4 is important for interns because it helps you understand that, even if your clients are experiencing a common problem (like poverty), this doesn’t mean that they are all experiencing this issue the same. Likewise, your own experience as an intern will be influenced by the identities that you recognize. Some classmates will experience their fieldwork differently because of their own intersecting identities. You may have experienced the same issue your clients are dealing with (such as poverty, illness, or unplanned pregnancy), but that does not mean that your experiences are the same. It pays to be cautious about making assumptions about others’ experiences and to be aware of how our own identities are influencing our own view of the world.

Diversity Is More than Just Culture Licenses and Attributions

“Diversity is More Than Just Culture” written by Ivan Mancinelli-Franconi PhD and Yvonne M. Smith LCSW is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Understanding Intersectionality” from “Intersectionality” in Kang, M., Lessard, D., Heston, L., & Nordmarken, S. Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies. CC BY 4.0. Edited for brevity, context, and addition of examples.

Figure 4.1 Infographic: “A More Diverse Nation” by the U.S. Census Bureau is in the public domain.

Figure 4.2 Bronfenbenner’s Ecological Model is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 4.3 “Visual Representation of SHARP Framework” © Wendy Shaia is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 4.4 “Social identity wheel” by Liz Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

the shared beliefs, customs and rituals of a group of people

the practice or quality of including or involving people from a range of different social and ethnic backgrounds and of different genders, sexual orientations, etc. that may or may not intersect with each other.

a way of looking at and acting on issues of justice to ensure that outcomes in the conditions of well-being are improved for marginalized groups, lifting outcomes for all.

the quality of being fair and impartial and providing equitable access to different perspectives and resources to all students.

the practice or quality of providing equal access to opportunities and resources for people who might otherwise systemically be excluded or marginalized, such as those who have physical or mental disabilities and members of other minority groups.

a difference in the distribution or allocation of a resource between groups.

a law written by a legislative body.

a method of defining and understanding the different elements involved in creating and maintaining poverty

the social act of placing severe restrictions on an individual group, or institution.

inequalities produced by simultaneous and intertwined social identities and how that influences the life course of an individual or group.

(or internship/practicum) experiential learning contained within human services programs. For the purposes of this text, fieldwork, internship, and practicum will be used interchangeably.